and to ছৈনিলি or ছিনারি on the other; the form ছিনার which occurs in Hem Chandra's দেশী নামমালা under a misconception, has been the form in Hindi, as well as in Bengali. I have to add, that the metre of the following verse was never adopted in Oriya, and the term ধনি for a woman has been the special property of Bengal.

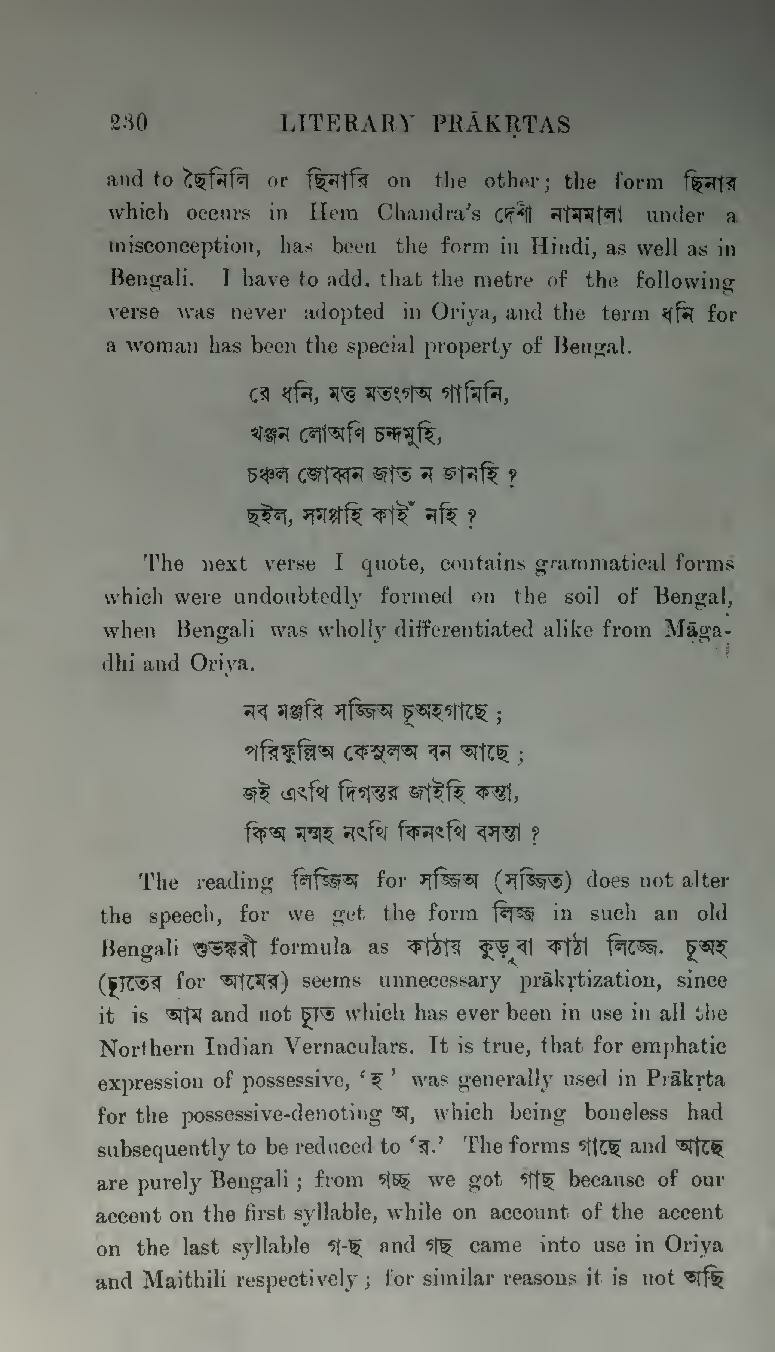

রে ধনি, মত্ত মতংগঅ গামিনি,

খঞ্জন লোঅণি চন্দমুহি,

চঞ্চল জোব্বন জাত ন জানহি?

ছইল, সমপ্পহি কাইঁ নহি?

The next verse I quote, contains grammatical forms which were undoubtedly formed on the soil of Bengal, when Bengali was wholly differentiated alike from Māgadhi and Oriya.

নব মঞ্জরি সজ্জিঅ চূঅহ গাছে;

পরিফুল্লিঅ কেসুলঅ বন আছে;

জই এৎথি দিগন্তর জাইহি কন্তা

কিঅ মম্মহ নৎথি কিনৎথি বসন্তা?

The reading লিজ্জিঅ for সজ্জিঅ (সজ্জিত) does not alter the speech, for we get the form লিজ্জ in such an old Bengali শুভঙ্করী formula as কাঠায় কুড়ুবা কাঠা লিজ্জে. চূঅহ (চ্যূতের for আমের) seems unnecessary prākṛtization, since it is আম and not চ্যূত which has ever been in use in all the Northern Indian Vernaculars. It is true, that for emphatic expression of possessive, 'হ' was generally used in Prākṛta for the possessive-denoting অ, which being boneless had subsequently to be reduced to 'র.' The forms গাছে and আছে are purely Bengali; from গচ্ছ we got গাছ because of our accent on the first syllable, while on account of the accent on the last syllable গ-ছ and গছ came into use in Oriya and Maithili respectively; for similar reasons it is not অছি