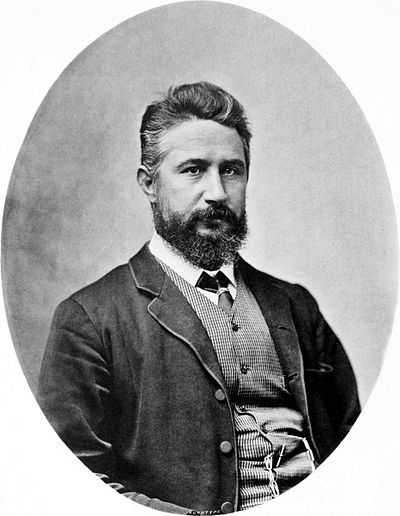

Plate II.

PORTRAIT OF AUTHOR, J. W. LINDT, F.R.G.S.

To face Preface.

PREFACE.

OR years past, when perusing the account of exploring expeditions setting out for some country comparatively unknown, I always noticed with a pang of disappointment that, however carefully the scientific staff was chosen, it was, as a rule, considered sufficient to supply one of the members with a mahogany camera, lens, and chemicals to take pictures, the dealer furnishing these articles generally initiating the purchaser for a couple or three hours' time into the secrets and tricks of the "dark art," or when funds were too limited to purchase instruments, it was taken for granted that enough talent existed among the members to make rough sketches, which would afterwards be "worked up" for the purpose of illustrating perhaps a very important report.

OR years past, when perusing the account of exploring expeditions setting out for some country comparatively unknown, I always noticed with a pang of disappointment that, however carefully the scientific staff was chosen, it was, as a rule, considered sufficient to supply one of the members with a mahogany camera, lens, and chemicals to take pictures, the dealer furnishing these articles generally initiating the purchaser for a couple or three hours' time into the secrets and tricks of the "dark art," or when funds were too limited to purchase instruments, it was taken for granted that enough talent existed among the members to make rough sketches, which would afterwards be "worked up" for the purpose of illustrating perhaps a very important report.

Sir Samuel Baker remarks, in the Appendix to one of his Works, that a photographer should accompany every exploring expedition. The only one I ever heard of being furnished with that commodity was H.M.S. "Challenger," on her scientific cruise round the world, but I remember reading in the "Photographic News" the complaint of a gentleman, that so many years had already passed, and still there was no sign of the "Challenger" photographs ever becoming accessible to the public.

How this is, or why it should be so, is difficult to tell, but as yet no book of travel, entirely illustrated by artistic views and portraits taken direct from nature, has come under my notice. According to my belief, there can be but one reason for it, and that is the difficulties encountered to find a competent artist photographer willing to join an expedition are greater than those necessary to secure the services of someone who can sketch, and hence artistic photography, the legitimate and proper means to show friends at home what these foreign lands and their inhabitants really look like, is set aside for drawings, either partly or purely imaginary[1].

Ever since I first passed through Torres Straits in September, 1868, I conceived an ardent desire to become personally acquainted with those mysterious shores of Papua and their savage inhabitants. I travelled this route on board a Dutch sailing vessel, and weird indeed were the tales that circulated among the crew concerning the land whose towering mountain ranges were dimly visible on our northern horizon. But years passed by, and time had almost effaced the impression, until I made the acquaintance of Signor L. M. D'Albertis, the intrepid Italian, who explored the Fly River higher up than anyone has ventured since. This occurred in 1873. Signor D'Albertis visited the Clarence River, in New South Wales, where I lived for many years, by way of recruiting his health after his voyages to N. W. New Guinea. How I fretted that circumstances prevented me from accompanying him on his first trip in the "Newa," and how I envied young Wilcox (the son of a well known Naturalist residing on the Clarence) being engaged as assistant collector, no one knows but myself. Again some years elapsed, and when next I met D'Albertis it was at Melbourne, in 1878. His personal reminiscences, and subsequently the reading of his interesting work, powerfully awakened my desire again for a trip to New Guinea. But circumstances were still adverse, and it was only when rumours of annexation became rife, and the Rev. Mr. Lawes visited Melbourne early in 1885, that the prospect of visiting the land of my dreams began to assume a more tangible form.

Mr. Lawes, hearing me speak so enthusiastically about my long cherished desire, assured me of his readiness to assist, and of hospitality, should I come to Port Moresby. The reverend gentleman's kindness and goodwill were amply proved, as my narrative will show, but be it here recorded, with due deference, I believe he doubted at that time the likelihood of ever seeing me sit at his table in the broad verandah of the mission house, listening to Mr. H. O. Forbes' reminiscences of the interior of Sumatra (the exhumation and ultimate fate of "that Kubu woman" to wit).

A month or so after Mr. Lawes' departure from Australia, the papers reported the intelligence that Sir Peter Scratchley had been appointed High Commissioner for the Protectorate of New Guinea, and that a properly equipped expedition was to be sent to investigate the newly acquired territory. Now or never was my chance. Colonel F. T. Sargood kindly introduced me to Sir Peter, I offered to accompany the expedition as a volunteer, finding myself in every requisite, and giving copies of the pictures I should succeed in taking in return for my passage and the necessary facilities to develop and finish my negatives on board.

My offer was accepted by Sir Peter, and on July 15th, 1885, I received notice to join the "Governor Blackall," the vessel selected for the expedition, then lying in Sydney Harbour.

The command of the "Governor Blackall" was entrusted to Captain T. A. Lake, the senior captain of the A. S. N. Company's fleet, who, throughout the voyage, sustained his high character as a skilful navigator among coral reels, and proved himself a man of tact and decision, qualities that were more than once put to the test during our cruise. Before launching into the description of the expedition, I wish to record here my deep sense of obligation to the gentlemen who kindly aided in the production of this Work by contributing chapters of valuable information. In the first place my thanks are due to the Rev. James Chalmers, who kindly continued the thread of the narrative, and brought it to a conclusion, when I was obliged to leave the expedition at Samarai (Dinner Island) about a month before the lamented death of Sir Peter Scratchley. I am also greatly indebted for his interesting paper on "The Manners and customs of the Papuans." On that subject no better source of information than him could be found. To Mr. G. S. Fort I offer my best thanks for presenting me with his Official Report of the Expedition. The same recognition is due to Sir Edward Strickland, the President of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia, for the permission to embody in my journal the interesting account of the "Bonito" Expedition, undertaken under the auspices of the Royal Geographical Society almost simultaneously with ours. My appeal to Mr. Edelfeld, now exploring in Motu Motu, met with a ready response from that gentleman in the shape of travelling experiences in the neighbourhood of Mount Yule. Last, but not least, I have to thank my learned countryman and friend. Sir Ferdinand Baron Von Müller, the eminent Botanist, for the promise of a valuable essay from his pen, although, unhappily, the pressure of departmental work on his hands is at present so severe that his contribution cannot be ready for this, the first edition of my book; and I cannot conclude without acknowledging my indebtedness to Commander H. Field, of H. M. Surveying Schooner "Dart," and to his able officers, Lieutenants Messum and Dawson, not forgetting Dr. Luther, who, with their uniform kindness and courtesy, made my return journey on board that vessel a perfect pleasure trip.

Melbourne, 1887.

P.S.—With regard to the publication of this Work much credit is due to Mr. Bird, of the Autotype Company. Arriving as I did, a stranger in London, this gentleman materially lightened my labours by introducing me to Messrs. Longmans, the publishers, and contributing his experience freely. My thanks are also due to Mr. Sawyer and his clever staff, for the masterly reproduction of my pictures, upon which the success of the book mainly depends.

- ↑ Though this book was written and the pictures taken under this impression, I found, on arrival in England, that several works of travel illustrated by photography have been published. I had the pleasure of meeting Mr. John Thomson, F.R.G.S., of Grosvenor Street, who showed me his magnificent and interesting work on "China and its Peoples." I examined also Sir Lepel Griffin's clever work, "Famous Monuments of Central India," and a little book on Tahita, by Lady Brassey, ably illustrated by Col. H. Stuart-Wortley. The illustrations in these Works consist without exception of photographs printed in autotype, and the inspection of these books and their pictures at once put me face to face with the countries described and their inhabitants, far more vividly than could works illustrated by wood engravings, where, for truth, the reader depends firstly on the individual conception of the artist, and secondly on the skill of the engraver.