Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London/Volume 25/On some recent Discoveries of Flint Implements of the Drift in Norfolk and Suffolk

(Read April 28, 1869[1].)

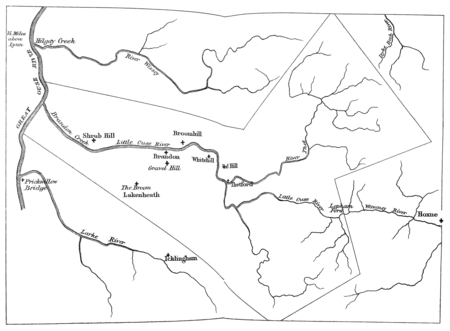

[Plate XX.]

In June 1866 I had the honour to lay before the Society a paper upon some flint implements then lately found at Thetford in the valley of the Little Ouse river[2]; I have lately occupied myself with further investigations of the same district, the results of which, are, I trust, of sufficient interest to justify me in bringing them to the notice of the Society.

The localities which I have now examined are four in number. In each of these flint implements have been found, and in several of them in great abundance, corresponding in the main, as well in fashion as in material, with those of St. Acheul, Thetford, Salisbury, and Icklingham, which are now so well known.

Broomhill.—The first deposit which I have to notice is found at Broomhill, on the north bank of the river, about five miles from Thetford, and two from Santon Downham mentioned in my former paper. The implements, which are usually much rolled and worn, and are often stained to a chocolate-colour, are here found in a gravel-pit about 350 feet from the river-bank. They are usually met with in a bed of ferruginous flint-gravel about 2 feet thick, resting immediately on the surface of the chalk, and 5 or 6 feet above the level of the river. This gravel, which is very coarse and not much rolled, contains large flint nodules, some of them weighing over a hundredweight, and is mixed with rounded quartzite pebbles and rolled fragments of chalk. It is overlain by another stratum of gravel, less ferruginous and containing a greater proportion of broken chalk; and this bed, in its turn, is capped by a mass of siliceous sand, sparingly intermixed with angular flints of no great dimensions. These several beds constitute a mass of from 25 to 30 feet in thickness. No gravel is found on the opposite bank; the ground there, which is moor or fen, rises very slightly above the river-surface, and forms a plain extending about half a mile to the base of the chalk-hills.

Gravel Hill, Brandon.—At this place, situate two miles and a half west of Broomhill and on the Suffolk side of the river, another deposit is met with, the position of which, however, is essentially different from that found at Broomhill. From a careful survey which

Plan of Gravel Hill, Brandon.

+ Gravel-pits.—Height 90⋅62 feet, from A to B, taken from the level of the river. Distance from the river 78 chains.

I have lately made it is found to be 91 feet above the river, and very nearly a mile distant from it at the nearest point; it comprises an area of from thirty to forty acres, occupying the summit of a hill overlooking an extensive sandy plain, which at a short distance merges in the great level of the fens. The bed of gravel here is usually not more than 10 feet in thickness, and often less, resting immediately upon the chalk; and, as at Broomhill, the implements are usually found at the bottom of it, and occasionally they lie upon the chalk. As regards its composition, however, no less than its position, this gravel differs greatly from that found at Brandon; the nodules of flint are not so large, there is very little of the broken chalk, and the mass of the overlying sand is much less.

By far the larger proportion (perhaps three-fourths of the whole mass of gravel) consists of rounded quartzites, and a few jasper-pebbles, while at Broomhill the proportion of these is hardly a thirtieth part of the whole. In some spots, indeed, these pebbles form a compact mass with hardly a single flint; and under one of these, at a depth of 6 feet, I procured a very well-shaped implement. The implements here are not generally stained of so deep a colour as those at Broomhill; and while many of them are of very coarse workmanship, and much worn and broken, others are of excellent forms, and as sharp and fresh as when first made.

Lakenheath.—The next deposit which I have examined is at Lakenheath, Suffolk, distant three miles from the left bank of the river. It is found on some high ground known as the Broom, between Lakenheath and Eriswell, and is at about the same height above the river, and of the same character as that at Gravel Hill, from which it is separated only by a shallow valley. These hills are only two miles and a half apart, and the beds which now cap them were doubtless at one time continuous. There is not so much, quartzite and jasper here, nor is the gravel so ferruginous as at Brandon; and being worked for the parish roads, and not for sale, as in the other pits, fewer flint implements have been obtained from it. The gravel extends over an area of about 60 acres, and lies immediately upon the chalk, to the same depth as at Brandon—8 to 10 feet.

Shrub Hill, Feltwell.—This deposit differs materially from the others; it is found on a farm known as Shrub Hill farm, situate in the fen on the Norfolk side of the river, and about eight miles below Gravel Hill. The implements occur in, or rather beneath, a patch of coarse flint-gravel and sand, which is apparently completely isolated. The chalk is here wanting, and the gravel, which is spread over an area of more than twenty acres, reposes immediately upon the surface of the gault. This bed, which is now extensively worked, was until lately quite unknown, the gault and the gravel being alike effectually concealed by the great bed of peat which just covers them. Although not laid down in any map, this gault is evidently a continuation of the bed, portions of which are shown in the Society's map, at Downham, Cambridgeshire, to the south, and Stoke Perry, Norfolk, to the north.

The gravel here is about 12 feet in thickness, but at the surface it is only 6 feet above the river. The implements here, as at the several other places above described, are, with very few exceptions, found at the bottom of the gravel, and not seldom they are lying upon the surface of the gault; they are usually much worn and rolled, and occur in considerable numbers: the gravel here is unstratified, and contains much less quartzite than at Brandon, and the overlying sands do not attain to so great a thickness.

Both at Broomhill and Brandon, as well as at Shrub, the implements are found in considerable quantities; I have procured several hundred specimens, sometimes as many as a hundred at a time. Other collectors have also visited the pits, and I have no doubt that there have been at least 1500 specimens procured from them within the last two years. When it is considered how many must escape the notice of the workmen, we may well believe that the valley of the Little Ouse is as prolific of these objects as that of the Somme, if not more so.

It has been usual hitherto to consider them as divisible into three kinds,—the flakes, the pointed, and the ovoid; but several others may, I think, now be distinguished. One implement, from Shrub Hill, which was found on the surface of the gault, is probably the largest yet discovered in England or France; it is 1112 ins. long, and its circumference at the thickest part is 13 inches. Two of those procured from Brandon are formed from quartzite-pebbles similar to those among which they are imbedded. Mr. John Evans has also found one of the same material, although of a somewhat different form, and he has obtained a well-shaped implement of diorite from the same place; in each of these a portion of the original surface remains. These, I believe, are the only instances in which such materials are known to have been used in England for implements of this age. With these exceptions, all the specimens that have been found were formed from nodules of chalk-flint which it is probable had previously been long exposed upon the surface. Many of the flints found with the implements have been fractured by internal expansion, resulting probably from atmospheric influences; some of the implements themselves have been made from stones thus broken, and others were broken by the same means afterwards. Many points and butts are also found, which doubtless were broken in the process of manufacture, the fractured surface retaining precisely the same patina or stain as the worked surface.

Although the implements of this district bear a certain general resemblance to those with which we are familiar from the Somme, as well as to those of Salisbury, and Hoxne, and Icklingham, I think that some slight differences may be detected as regards shape and workmanship; and indeed it seems by no means certain that the implements found at Broomhill do not differ from those at Brandon. Thus at the former place they are often of a wedge-like form, resembling rudely a shoe or foot with a high instep, a variety which is not found at Brandon; while at the latter pits they sometimes occur of a large leaf-like pattern, about 8 inches long by 4 wide and only 2 inches thick at the thickest end, tapering off to 14 of an inch. I have never met at Shrub Hill or Broomhill with any others of this form. In other localities differences have been noticed in the implements found in deposits quite as near to each other as these. Those of St. Acheul differ from those found at Montiers; and Mr. E. T. Stevens, who has so carefully studied the Wiltshire implements, assures me that the group found at Bemerton is of a type decidedly different from those at Milford Hill, a mile and a half distant, and that both of these differ from those found at Hill Head in Hampshire. Possibly each place may have had its own workmen, and perhaps in some cases different shapes were used to meet different requirements. It would be inconvenient to attempt here to give a detailed account of these differences; and, indeed, much longer and more careful observation is needed before we can arrive at any certain conclusions on the subject.

No shells, either fluviatile or marine, have as yet been discovered in either of the several deposits above described; but since my former paper was published, I have found at Thetford a thin seam of fine white sand, with a few land and freshwater shells, lying some feet above the gravel in which the implements occur. Two teeth of Elephas primigenius, as well as some bones of Bos Urus, have also been found in the Thetford gravel; and from Shrub Hill I have some fragments of the horns of deer, and teeth of some ruminant, probably deer also, as well as some teeth of a small species of horse, all much broken and rolled; with these exceptions I believe that no mammalian remains have hitherto been noticed in these beds, nor any other traces of man's presence than the flint and stone implements.

The geography of the district, with reference to other places in the neighbourhood in which implements have been found, will be understood by reference to the accompanying map (Pl. XX.). At about three miles distance from Broomhill and Brandon, on the north, a high tableland, of about a mile in width, divides the valley of the Little Ouse from that of the Wissey (which flows in the same direction). This hill (which forms the watershed of both rivers) is capped with drift- gravel and siliceous sands closely resembling those seen at Brandon, the quartzite pebbles, however, being somewhat less abundant[3]. On the south side the river is bounded for some distance by the hills at Brandon and Lakenheath, on which the implements occur; and about seven miles further south, in the Larke Valley, at Icklingham, another well-known deposit of implements has been met with. West of these several localities is seen the great level of the Fens, extending through Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, and Huntingdonshire into Northamptonshire and Lincolnshire, while to the eastward, passing by Santon Downham and Thetford, the Little Ouse is traced back to its source at Lopham Ford; and closely adjoining to the source, and only separated from it by a bank of sand 5 or 6 feet high and 200 yards wide, is found the source of the Waveney, which after running north-east, passing by Hoxne (another locality for flint implements), falls into the sea at Yarmouth[4]. There seems to be little doubt that these valleys (of the Ouse and the Waveney) are derived from one continuous valley of submarine erosion, by which Norfolk was formerly cut off from the rest of the kingdom, and constituted an island.

We have clear evidence that even within the historical period the district to the westward through which the river flows, after leaving Brandon, was at a much lower level than at present, the valley having been filled up with peat, and thus brought to a dead level, or nearly so, extending over many hundred square miles. Polished flint implements of the Neolithic period have been often found lying below the peat or low down in it, as well as bronze celts and spear- heads; the peat varies in thickness from 1 or 2 feet to 20. or even 30 feet, and in it are found querns of pudding-stone and Roman antiquities. In many places in the level of the fens other unmistakeable proofs have been met with of the comparatively recent origin of these beds. In one place swaths of grass lying just as they were mown were found at the depth of 8 feet, and in other places, at depths varying from 10 to 20 feet, there have been found a smith's forge with his tools and horseshoes, tan-pits, a cart-wheel, and ancient causeways, and the skeletons of sea-fish, and boats or canoes. It also appears, from the depositions of witnesses laid before Parliament in 1696 in support of a petition for the removal of Denver Sluice, that, prior to 1650, when the sluice was erected, the tide flowed twenty-four miles further than it then did into "the deep rivers of Ouse, Stoke (the Wissey), Grant (the Cam), and Mildenhall (the Larke);" and one witness deposed that before the dam was built the tide flowed up to Wilton Lode, which is just two miles from Brandon, and at the foot of the hill above described[5].

From these details it will be seen that these beds in every material particular bear a close resemblance to those of the Somme, which have been so well described by Mr. Prestwich. In each, the implements are for the most part found in a bed of coarse flint-gravel, which rests immediately upon the chalk, and is overlain by other masses of gravel and siliceous and calcareous sands. In both deposits the implements are of the same material, the same, or nearly the same fashion, in similar condition, and associated also with similar mammalian remains, and each is destitute of those fossils which are wanting in the other. This remarkable correspondence between these beds in the South-east of England and those of the north of France not only tends to confirm the opinion which has been formed on other grounds, that at the commencement of the Quaternary epoch the two countries had not been severed, but leads to the belief that even at this early period they were inhabited by man.

Nor is the resemblance which these valleys bear to each other confined to the lower beds. In both, as we approach the coast, and at about the same distance from it, the drift-gravel is overlain by a thick bed of peat, which entombs the remains of ancient forests of similar character, and in either country is found to contain similar mammalian remains, associated with implements or weapons of like material and workmanship. We have thus the same evidence in both countries that the first known stage of the Quaternary period has passed away, and a new and well-defined era has arrived. In England, as in France, the great Pachyderms have entirely disappeared, and are succeeded by a new fauna adapted to new conditions, and to be superseded in due time by other creatures and other conditions. As the Beaver, Wild Boar, Bos longifrons, the Roe, and the Red Deer have replaced the Elephant, the Rhinoceros, and the Hippopotamus, so instead of the rude implements fabricated by the men who were contemporary with these animals, the fens of Norfolk and Cambridgeshire as well as those of Picardy are found to contain the polished flint and stone implements of a far later period, and pudding-stone querns of precisely similar material and form.

Such being the phenomena presented to our notice, it remains to consider what light they throw upon the origin and history of the implements. Hitherto it has been usual to place them in the same category with the beds in, or beneath, which they occur; they are regarded merely as the characteristic fossils of certain river-valley gravels, without reference to the condition of either previous to their being brought together. But although the conditions of either deposit can hardly fail to throw light upon the history of the other, each has undoubtedly a history and (geologically) a date of its own; the implements, although in the gravel, are not of it, except in a certain limited sense. The one is the product of human skill, the other the result of natural causes; and it is essential to consider them separately, as well as in their connexion with each other.

When first observed, the implements had always been found in the immediate neighbourhood of river-channels, and assuming (as it seems usually to have been assumed) that they had been carried from the places in which they were made, it was reasonable to ascribe their transport to those rivers; but this was but a presumption which, however reasonable, was liable to be rebutted. Because certain objects are found in or near the banks of rivers, it by no means follows that they must of necessity have been carried thither by the rivers; they may have been deposited by other means, and possibly even before the rivers had an existence, and there seems good reason for believing that as regards many, or indeed most, of these flint implements this may have been the case.

At the commencement of the Quaternary epoch, when, by the retiring of the sea, or the elevation of its bed, the Cretaceous and Tertiary strata became dry land, it cannot be doubted that the surface, in many places, was, as it still remains, strewn, especially in valleys and hollows, with fragments of various rocks—the wreck and ruin of beds which had been broken up and dispersed. Of these a large proportion would consist of nodules of flint which had been washed out of the upper chalk-beds, or from which the chalk had been removed by decomposition. Abundant materials would thus be provided for the makers of implements and weapons, and the fol- lowers of this primitive industry would naturally resort to those spots on which the best material was to be found. The condition in which we find them is quite consistent with the belief that the stone from which the implements were formed had previously been long exposed upon the surface. At one time, therefore, the raw material and the manufactured were alike lying upon the surface, and after some interval of unknown but probably very extended duration, both were alike overwhelmed by those masses of sand and gravel beneath which we now see them. This interval doubtless involved important changes, including perhaps the obliteration of ancient river-channels and the formation of new ones.

If, as has been sometimes supposed, the implements were carried about by river-floods, or by deluges, whether marine or of fresh water, we should expect to find them confusedly intermingled with the sands and gravels, and they would be strewn continuously along the whole course of the valleys. This, however, seems not to be the case; for although the gravel-beds are continuous (frequently for several miles), the implements hitherto have been found only at detached spots, often far apart, and which were probably visited on account of convenience of access or better materials. And instead of being blended with, the higher beds (with some exceptions, which are probably attributable to the displacement and reconstruction of the original deposit), they are found in the lowermost stratum—that which rests immediately upon the Cretaceous or Tertiary beds, and which would be left bare when these became dry land.

It is true that occasionally, although comparatively rarely, implements are found lying above the lowest bed; but this is not inconsistent with the belief that they were originally deposited at the lower level, which I regard as their ordinary or normal position. Unlike marine deposits, which are usually those of accretion, the changes which are effected by river- or deluge-agency are those of denudation and dislocation; and it is evident that after the lowest stratum was constituted it was overwhelmed by other very considerable masses, which could only have been transported by powerful torrents. These, in their course, conveying rocks of considerable magnitude, could not fail to some extent to break up the subjacent beds, and in this way some implements would be taken from their first place of deposit, and left at relatively higher levels. As every inundation disturbs, and partially, if not entirely, effaces the traces of that which preceded it, so the upper portion of any bed may be carried away and form a new deposit, upon which the lower portion may afterwards be thrown, and thus the position of each becomes reversed. The worn appearance of some specimens, as compared with the fresh and sharp condition of others, tends to show that, while the latter have been but little, if at all, displaced, the former have been subjected to much rolling and attrition.

The circumstance that some implements are found lying above the lowermost stratum of gravel is thus not inconsistent with the belief that the stones from which they were wrought were nevertheless taken from that bed, and that they are thus to be ascribed to the commencement of the Quaternary period. On the other hand, if we should reject this view, we should be forced to conclude that the process of manufacture was continued through the very lengthened periods that would be requisite for the excavation of the existing river-valleys, involving the assumption, so difficult of acceptance, that although these implements were fabricated and used by many successive generations, they all passed away without leaving any other trace of their existence; and we must also suppose a constant recurrence of those agencies, whatever they may have been, by means of which these things were buried under thick masses of gravel and sand.

Under all the circumstances, therefore, it seems probable that the implements for the most part were not transported by any river or flood, but that they were made, or left, at or near the spots where we find them, although in some instances, especially in valleys and watercourses, they may have been afterwards displaced.

But even if it were otherwise, if it were certain that they were brought into their present position at the same time with the beds of gravel in which they occur, and by the same means, the belief that those beds were deposited by the agency of rivers involves so many difficulties and objections, that it can hardly be accepted without much further consideration than the subject has received, much as it has been discussed. Indeed, unless we are prepared to admit that all the Quaternary gravels were brought to their present places of deposit by the agency of rivers (which is evidently impossible), it is unreasonable to attribute to that agency any particular portion of those gravels merely because they happen to contain implements.

Considerable differences of opinion exist between French and English geologists as to the causes which led to the accumulation and distribution of those superficial drifts in the south-east of England and north of France of which the flint-implement-bearing beds form part: while the French geologists unanimously attribute them to some kind of cataclysmal or diluvial action (although they differ among themselves as to its particular character), the English geologists are nearly unanimous in ascribing them to the action of existing rivers, or at least of rivers which then ran in the same direction as they now do, and drained the same areas. The present is not a convenient occasion for considering this subject at any length. I propose only to show how inadequate, as it seems to me, is the theory of fluviatile transport to explain the condition of the deposits before referred to and of others of a like character.

The opinion of English writers cannot be better stated than in the words of Mr. Prestwich, from the able and exhaustive memoir upon the flint-implement deposits read by him before the Royal Society in 1862. He says, "that certain beds of gravel, at various levels, follow the course of the present valleys, and have a direction of transport coincident with that of the present rivers, and that the extent and situation of some of these beds so much above existing valleys and river-channels, combined with their organic remains, point to a former condition of things when such levels constituted the lowest ground over which the waters passed;" further, "that the size and quantity of débris afford evidence of great transporting power; while the presence of fine silt, with land shells, covering all the different gravel-beds, and running up the combes and capping the summit of some of the adjacent hills to far above the level of the highest of these beds, points to floods of extraordinary magnitude;" that "these conditions, taken as a whole, are compatible only with the action of rivers flowing in the direction of the present rivers, and in operation before the existing valleys were excavated through the higher plains, of power and volume far greater than the present rivers, and dependent upon climatal causes distinct from those now prevailing in these latitudes"; and he adds that "such a result might formerly have been obtained, 1st, by a direct increase in the rainfall; 2ndly, by the accumulation and rapid melting of the winter snow, or by the two causes combined; and 3rdly, by the fall of rain in the spring while the ground was in a frozen state."

Mr. Prestwich's opinions have been acquiesced in both by Sir Charles Lyell and Sir John Lubbock. The latter, in his preface to the recent English edition of Sven Nilsson's 'Primitive Inhabitants of Scandinavia,' when speaking of the antiquities referable to the Palæolithic age, says "that they are usually found in beds of gravel and loess, extending along our valleys, and reaching to a height of 200 feet above the present water-level;" and he adds, "that these beds were deposited by the existing rivers, which then ran in the same direction as at present, and drained the same areas."

As long as it was believed that the implement-bearing gravels were never found except on or very near to the banks of rivers, it was reasonable to attribute to those rivers the transport of the gravel in which they were imbedded; but from more recent observations, both in England and France, it seems evident that the implement-bearing gravels, as well as others of the same character, which are not yet known to contain implements, do occur in localities so far removed from existing rivers, and, when found near rivers, at such elevations as almost to preclude the belief that those rivers, however swollen by excessive rainfall or melting snow, or otherwise, could have at all affected their condition.

Thus, for instance, as we see at Brandon, the implement-deposit occurs at an elevation of from 80 to 90 feet above that at Broomhill (which is two miles higher up the stream), and about the same above Shrub Hill, which is several miles lower down. Yet, notwithstanding this great difference in the levels, we have strong, if not unmistakeable indications, derived in some measure from the implements themselves, that all these deposits were (geologically) contemporaneous. The implements in each are substantially of the same age and character; the matrix of red gravel, in which they rest, is of the same composition; the beds rest directly upon the eroded surface of the chalk or the gault, and are more or less overlain by sands of the same description. But it is incredible that such deposits (if of the same age), should owe their origin to one and the same river; for if so, in order to reach the higher level, it must have been swollen to the height of 100 feet above the level at Broomhill and Shrub, and extended three miles to the south. This would require a volume of water of dimensions and power several thousand fold greater than those of the present river; and to supply such a stream, the basin from which the river is fed (occupying as it does an area of not more than 300 square miles) is altogether insufficient; nor, indeed, would the present contour of the country allow such a river to flow in that direction.

Nor would the difficulty be removed or lessened if we were to disregard those proofs of contemporaneity to which I have adverted, and to assume that these deposits were separated from each other by an interval of time sufficient to allow of the excavation of the existing river-valley to the depth of the 80 or 90 feet which now divide it from the Brandon bed. We have no reason whatever to believe that, in these districts, the relative levels of the surface have undergone any material change during the Quaternary period[6]; and, if not, in order to account for the Brandon and Lakenheath deposits, we must suppose that this river once flowed at a height at least 100 feet above the present stream, and afterwards altered its course, and flowed several miles to the north. But this could never have been the case: for, just as at Moulin Quignon and Saint Acheul the gravel-beds described by Mr. Prestwich are not commanded by any higher grounds, and are out of reach of all running water, and of any possible interference from agents in present action, so here they are found at an elevation of at least 80 feet above the source of the river, which is not more than twenty miles distant, and there is no high land in the neighbourhood from which a river capable of leaving such a deposit could possibly have been supplied. It is equally clear that if the water had been supplied, it never could have reached to the summit of the hills. These, as I have shown, immediately overlook or overhang the great level of the fens, which was formerly a considerable valley, much of it having been filled up by peat within a period comparatively recent. Before the river could have attained to a height sufficient to submerge the hills and cover them with its spoils, it must have fallen into the low grounds on either side, and, filling up the valley, have found its way to the sea, or, if not, it would have formed an inland lake; in either case the transporting power of the water would have been lost long before it reached the required level.

In confirmation of the views here stated, I may notice that flint-implement-bearing gravels have lately been observed in several other localities, on table-lands and hills far removed from any existing river, and destitute also of the slightest trace of any ancient river.

At the Reculvers they are obtained from a small patch of flint-gravel on a cliff overhanging the sea, and 80 feet above it; while at Hill Head, in Hampshire, and at Bournemouth, Dorset, they have been found in similar situations and at greater elevations.

A still more remarkable instance has been described by Mr. Bruce Foote as occurring near Madras[7]. The implements here are made from pebbles of quartzite, and in form and workmanship are closely allied to the English and French types. They are found in a red ferruginous clay, known as laterite, which forms a belt eight or ten miles in width, running parallel with the coast-line for the distance of 300 miles. These beds are cut through at intervals, and to great depths, by the rivers of the country running at right angles to the coast-line, and falling into the Bay of Bengal. The implements are never found in the river-channels, except where it is clearly seen that they have been derived from the laterite cliffs. They occur at the height of 500, 1000, and even 1400 feet above the sea-level, and at this height are associated with enormously large boulder-gravels of quartzite capping the watersheds of the rivers. Like several French and English deposits, these beds rest upon the Cretaceous and Postcretaceous beds; like them they are entirely destitute of marine or freshwater fossils; and, like them also, they are frequently far distant from any river or river-channel[8].

The presence of freshwater shells in some of these beds has been regarded as indicative of their fluviatile origin; as far, however, as the evidence at present extends, this condition is the exception rather than the rule. When these gravels remain at what I regard as their original place of deposit, viz. immediately upon the chalk or gault surface, I believe that not a single river or lake shell has ever been found associated with them, or lying below them, either in the flint-implement-bearing gravels, or in the very extensive beds of similar gravel in the south and south-east of England and in the north of France, which are not known to contain implements. Certainly no shells have been seen in either of the four deposits above described; nor are there any at the Reculvers, Bournemouth, or Hill Head; and the gravels at Madras are equally destitute of them. The presence of these shells in the upper portion of these beds by no means involves the conclusion that they are of the same age as the underlying drift; for, assuming that that was formed and left as above suggested, the valleys and hollows would soon become lakes and rivers, into which in process of time freshwater mollusks would find their way; and whenever the lower beds should be broken up and reconstructed, the shells would be mingled with the débris, and thus become undistinguishable from the older deposits.

Another circumstance which has been relied upon as showing the fluviatile origin of these gravels is the absence of any rocks except those of the district through which the rivers take their course. I do not think that this is very clearly established[9]; but, assuming it to be so, it is quite consistent with the notion of diluvial transport that the loose objects found on the surface should not be transported out of their own district: rocks and stones, if swept away by a deluge, would very soon find their way into valleys and hollows, and be left there when the waters had retired.

In conclusion I would suggest that the distribution, in the first instance at least, of these drift-beds, containing, as they do, so large an admixture of chalk and tertiary and boulder-clay rocks, may reasonably be attributed to the same forces or conditions, whatever they were, by which the Tertiaries and Boulder-clays were broken up and their materials so widely dispersed and intermingled. We know nothing of these, except from their results; but, whatever they may have been, it seems quite certain that they are not ascribable to fluviatile agency, and I am therefore disposed, with the French geologists, to attribute them to some powerful cataclysmal action, perhaps of short duration, and several times repeated.

- ↑ For the Discussion on this paper, see p. 272 of the present volume.

- ↑ Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc. vol. xxiii. p. 45.

- ↑ Since this paper was read, I have visited this place in company with Mr. Prestwich. He considers this gravel to belong to the Boulder-clay series; and we certainly saw a capping of clay about a foot thick covering a portion of it. The implement-bearing gravel at Brandon is precisely of the same composition, although the quartzite-pebbles occur in much more compact masses. Mr. Prestwich, however, considers it to be a reconstructed gravel, and of subsequent date to that in the watershed.

- ↑ In the map published lately by the Society, Lopham Ford is stated to be only 15 feet above high-water mark at Lynn; but this is probably a mistake: the river at Brandon is found to be 15 feet above high-water mark, and the source at Lopham Ford is probably about eight feet higher.

- ↑ The confluence of the Little Ouse or Brandon river with the Great Ouse is still known by its ancient name as Brandon Creek, while that of the Wissey is known as Hilgay Creek.

- ↑ Phil. Trans. 1864, pp. 286–290.

- ↑ Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc. vol. xxiv. p. 484.

- ↑ Since this paper was prepared, Mr. John Evans has shown me three well-shaped flint implements lately found near Southampton, one at the depth of five

- ↑ M. Buteaux, in his very elaborate and careful description of the Somme valley, says that in the diluvium of that valley certain rocks are found which come from the Tertiary beds of the departments of the Oise and Aisne. Mr. Prestwich considers that the quartzite pebbles at Brandon are derived from the Boulder-clay series; but I am not aware that there are any Boulder-clays in the course of the river from which such a mass of these pebbles could have been derived.

feet in flint-gravel. Two were found near the Cemetery, at a height stated to be 110 feet above high-water mark, and a mile distant from the beach; the other was at a spot considerably higher and more inland.