Chapter II

WITH respect to tobacco, let it be defined as follows:—"Tabacus est herba in quâ inest nicotinica et soporifera virtus"—Tobacco is a herb in which resides a nicotinic and soporific virtue.

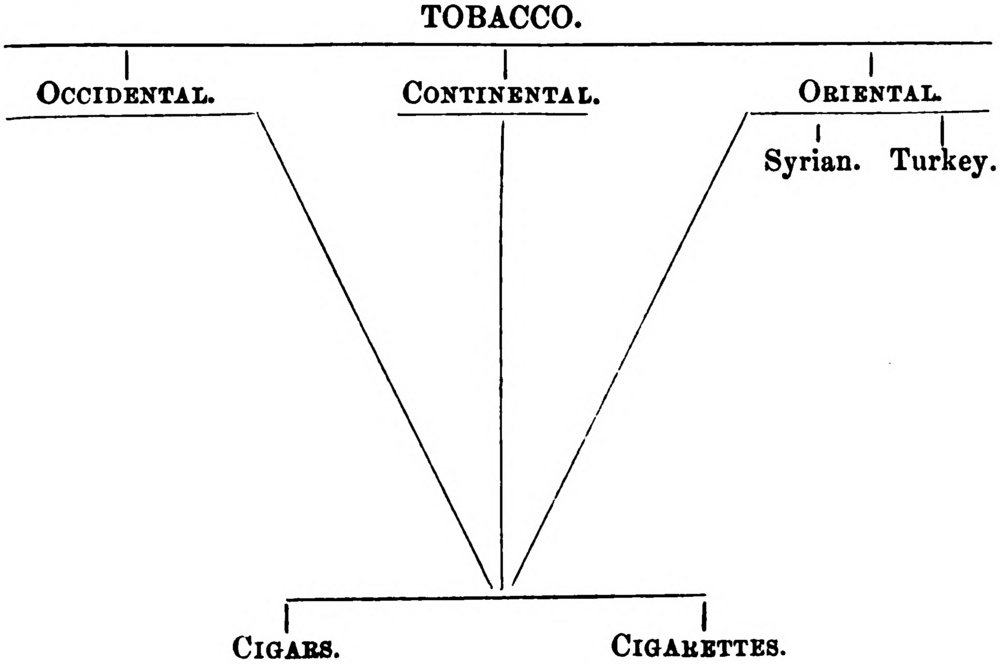

Next to definition cometh division, which, sooth to say, is somewhat difficult and requireth consideration. And the reason of this difficulty is to be imputed to a certain variant form of tobacco known as the cigar—that is to say, tobacco, not shred finely, but rolled and compacted in such a way as to be smokable without the medium of a pipe. Also there is another form known as the cigarette, which is shred tobacco constricted within a roll of thin paper. Some would differentiate these two forms and consider them apart, but I deem it unnecessary, and have devised a plan which compriseth all kinds within a small compass, which I here present thee with:—

Now methinks I hear many a one objecting to this synopsis, and pronouncing it as altogether meagre and imperfect, containing nought but a mere outline of the subject, and that done after a strange manner.

And in answer to such objections, if they be made, I reply as follows:—

First, as to the main plan, it is clear that all tobacco in ordinary use must come from one of three places. (1) From America, which I call Occidental or Hesperidian tobacco. (2) From Asia (under Asia I include Roumelia, though Mercator should reprove me). And this I call Oriental tobacco. (3) From the Continent of Europe, which I call Contienental tobacco. Secondly, as to the imperfection and bareness of the scheme. I imagine that the specific fault found with it will be that there are no Honey Dews, Golden Clouds, or Bird's Eyes under tobacco; and no Regalias, Reinitas, or Intimidads under cigars. The reason for this omission is that these are rather matters for the tobacconist to consider than the Pipe Philosopher, who, so far from bringing to every subject a microscopic meticulosity, knows well the limits and bounds of his science, and when to be full and when to be brief. And, in fine, were I to admit any of these distinctions into my synopsis it would be but an advertisement fit to be displayed in a booth, and altogether unmeet for the study of a philosopher. So I know nought of them; but in so far as the principal kinds have different qualities and influences on the mind and body of the smoker, they shall be briefly treated of in the second part of this book.

Next, with respect to differences between philosophers as to the nature of tobacco: mirabile dictu these are few and trifling, there being little dispute upon the matter. Only, as I have mentioned before, some would consider tobacco, cigars, and cigarettes separately, thinking thus to prevent those disputes which we shall come upon shortly as to the nature and essence of pipes. And in some wise there is wisdom in this, for if their division should obtain a great part of the grounds of difference between the philosophers of the bowl and the philosophers of the tube would be cut away, and they might be at one; but yet on the other hand these same contentions have led to an infinite amount of learned ingenuity and metaphysical refinement, which 'twere surely pity to render of no account. And further, besides that expediency is on our side, the present concatenation is assuredly good, valid, and just, and worth retaining for its own sake. For to separate cigars from tobacco would be as if in a natural history there were separate chapters—one treating of sheep shorn and the other of sheep unshorn, which were folly. For it is certain that cigars are tobacco, and come under the definition, "a herb in which resides a soporific and nicotinic virtue;" and therefore to treat of the two apart on a doubtful ground of utility would be grave error. Furthermore, to do so would "make harsh the liquid melodies"[1] of those famous lines beginning, "Q tabacum teneat," which is not to be borne. And so, by analogy, I think that these doctrines will not obtain, for, as is well known, some while ago a certain Scotch logician did bring forward amendments in the Art of Logic, which if they had been carried out, Barbara Celarent would have been abolished and done away with. But yet, notwithstanding the pretended utility of these improvements, Barbara Celarent vigentque valentque (as Ovidius writes of a different matter): nay, by all accounts, there be students at one of our Universities who will go further and (still with Ovidius) prefix intempestive or unseasonably, seeing that the ignorance of Barbara Celarent doth entail no small inconvenience and discomfort in the precincts of the Forum Suarium, or Pig Market.

Concerning tobacco, therefore, let such things have been said. And this is all that can be said as to definition.

- ↑ I use the words of Gossius, De Auctore Hesperidum.