CHAPTER XVII

AUSTRALIAN VOYAGES, 1851-1854

THE years between 1849 and 1856 were perhaps the most prosperous that ship-owners and ship-builders have ever known. The discovery of gold in Australia in 1851 had much the same effect as that in California in 1848, and people flocked to Melbourne from all parts of the world. There was this difference, however, that whereas passengers went to California, after the first rush, by steamers via Panama, and the mails and gold were always transported by this route, all the Australian passengers, mails, and gold were for a considerable period carried by sailing vessels. The extent of this traffic may be judged from the fact that the yield of the gold fields up to December 30, 1852, a little more than a year after their discovery, was estimated at £16,000,000 sterling, or $80,000,000. Prior to 1851 the emigration to the Australian colonies had been about 100,000 persons per annum, while the average between 1851 and 1854 was 340,000 annually. The transportation of these passengers alone required an enormous amount of tonnage, so that the discovery of gold in Australia gave an additional impulse to clipper ship building.

At this time the proper route to ports on that part of the globe had only just become known, although British ships had been sailing to and from Australia and New Zealand for many years, taking out emigrants and bringing back wool. They usually called at the Cape of Good Hope both outward and homeward bound, this being the route recommended by the Admiralty. One of the most important services rendered by Lieutenant Maury was his careful research in this matter, which resulted in an entire revolution of both outward and homeward tracks. Instead of sailing near the Cape of Good Hope outward bound, he discovered that a ship would find stronger and more favorable winds from 600 to 800 miles to the westward, then continuing her course southward to 48°, she would fall in with the prevailing westerly gales and long rolling seas in which to run her easting down. It was in this region that the Australian clippers made their largest day's runs.

The homeward bound Admiralty track was entirely abandoned by Lieutenant Maury in favor of continuing in the brave west winds, as he called them, round Cape Horn, so that a voyage to Melbourne out and home encircled the globe. By the old routes, vessels were usually about 120 days each way, though sometimes considerably longer. By the tracks which Lieutenant Maury introduced, the outward and homeward voyages were made in about the same time that had formerly been consumed in a single passage, though of course the increased speed of the clipper ships contributed to this result.

The misery and suffering of passengers on board the old Australian emigrant ships before the days of the clippers are difficult to realize at the present time, but there is an account compiled from the report of the Parliamentary Committee appointed in 1844 to investigate the matter, which reads as follows:

"It was scarcely possible to induce the passengers to sweep the decks after their meals, or to be decent in respect to the common wants of nature; in many cases, in bad weather they would not go on deck, their health suffered so much that their strength was gone, and they had not the power to help themselves. Hence the between-decks was like a loathsome dungeon. When hatchways were opened under which the people were stowed, the steam rose and the stench was like that from a pen of pigs. The few beds they had were in a dreadful state, for the straw, once wet with sea-water, soon rotted, beside which they used the between-decks for all sorts of filthy purposes. Whenever vessels put back from distress all these miseries and sufferings were exhibited in the most aggravated form. In one case it appeared that, the vessel having experienced rough weather, the people were unable to go on deck and cook their provisions; the strongest maintained the upper hand over the weakest, and it was even said that there were women who died of starvation. At that time the passengers were expected to cook for themselves, and from their being unable to do this the greatest suffering arose. It was naturally at the commencement of the voyage that this system produced its worst effects, for the first days were those in which the people suffered most from sea-sickness, and under the prostration of body thereby induced, were wholly incapacitated from cooking. Thus though provisions might be abundant enough, the passengers would be half-starved."

In an interesting book entitled Reminiscences of Early Australian Life, a vivid description is given of maritime affairs in 1853. The writer, who had arrived at Melbourne in 1840, says that: "Since that time the town of Melbourne had developed from a few scattered and straggling wooden buildings, with muddy thoroughfares interspersed with stumps of gum trees, into a well-built and formed city, with wide, and well-made streets, symmetrically laid out, good hotels, club houses, and Government buildings. Port Phillip Bay, in which two or three vessels used to repose at anchor for months together, was now the anchorage ground of some of the finest and fastest clippers afloat."

At this time (1853) upwards of two hundred fullrigged ships from all parts of the world were lying in the Bay. This writer continues: "After landing their living freight of thousands that were rushing out to the gold fields to seek for gold, and fearing that they might be too late to participate in their reputed wealth, ships now waited for return cargoes, or more probably for crews to take them home, as in many cases all the hands had deserted for the gold fields. On ascertaining that there were two good ships sailing for London, with cargoes of wool and gold-dust, about the same time, or as soon as they could ship crews—one the Madagascar, of Messrs. Green & Co.'s line, and the other the Medway of Messrs. Tindall & Co.'s line—I proceeded to the office and booked a passage by the Madagascar—the passage in those days for a first-class cabin being £80. After paying the usual deposit and leaving the office, I met a friend, who was also homeward bound, and on my informing him that I had booked by the Madagascar, he persuaded me to change my ship and go home with himself and others whom I knew in the Medway, and upon returning to the office of Green's ship, and stating my reasons for wishing to change to Tindall's ship, they were very obliging, and returned my deposit, stating that they could easily fill up my berth. It was well for me at the time that I changed ships, as the Madagascar sailed the same day from Port Phillip Head as we did, with four tons of gold-dust on board; and to this day nothing has ever been heard of her. She either foundered at sea, or, as was generally supposed, was seized by the crew and scuttled and the gold taken off in boats. All must have perished, both passengers and crew, as no tidings of that ill-fated ship ever reached the owners.

"On board the Medway there were four tons' weight of gold-dust, packed in well-secured boxes of two hundred pounds each, five of these boxes being stowed under each of the berths of the saloon passengers. Each cabin was provided with cutlasses and pistols, to be kept in order and ready for use, and a brass carronade gun loaded with grape shot was fixed in the after part of the ship, in front of the saloon and pointed to the forecastle—not a man, with the exception of the ship's officers and stewards, being allowed to come aft.

"The character of the crew shipped necessitated the precautions; for the day previous to the ship's sailing men had to be searched for and found in the lowest haunts and were brought on board drugged and under the influence of liquor, and placed below the hatches. We, the passengers, heaved up the anchor and worked the ship generally until outside of Port Phillip Head, when the men confined below, who were to compose the crew, were brought on deck, looking dazed and confused, any resistance or remonstrance on their part being futile. But those amongst them that were able-bodied seamen were paid in gold, forty sovereigns down, on signing the ship's articles for the homeward voyage.

"Amongst them were useless hands and some of a very indifferent character. Some, no doubt, were escaped convicts, or men who had secreted themselves to evade the police and law; others deserters from ships then laying in the Bay—about forty in all, and in general appearance a very unprepossessing lot. However, there being no help for it, we had but to keep guarded and prepared against the worst; the ship's passengers together with the officers numbering about twenty hands. The captain was an old and well-known sailor of high reputation and long experience; and the ship was well found and provisioned, in anticipation of a long voyage—which it proved to be, extending over four months from the time we left Port Phillip Head until she reached the English coast."

The first clipper ship constructed for the Australian trade was the Marco Polo, of 1622 tons; length 185 feet, breadth 38 feet, depth 30 feet. She was built in 1851 by Smith & Co., at St. John, N. B., for James Baines & Co., Liverpool, and was the pioneer clipper of the famous Australian Black Ball Line. The Marco Polo was constructed with three decks, and was a very handsome, powerful-looking ship. Above her water-line, she resembled the New York packet ships, having painted ports, and a full-length figurehead of the renowned explorer whose name she bore. Below water she was cut away and had long, sharp, concave ends. Her accommodations for saloon and steerage passengers were a vast improvement upon anything before attempted in the Australian trade.

She sailed from Liverpool for Melbourne, July 4, 1851, commanded by Captain James Nicol Forbes, carrying the mails and crowded with passengers. She made the run out in the then record time of 68 days, and home in 74 days, which, including her detention at Melbourne, was less than a six months' voyage round the globe. Running her easting down to the southward of the Cape of Good Hope, she made in four successive days 1344 miles, her best day's run being 364 miles. Her second voyage to Melbourne was also made in six months out and home, so that she actually sailed twice around the globe within twelve months. To the Marco Polo and her skilful commander belongs the credit of setting the pace over this great ocean race-course round the globe.

Her success led to the building of a number of vessels at St. John for British owners engaged in the Australian trade. Among these the most famous were the Hibernia, 1065 tons, Ben Nevis, 1420 tons, and Guiding Star, 2012 tons. In Great Britain also a large number of ships were built for the Australian trade between the years 1851 and 1854. Many of these were constructed of iron, the finest being the Tayleur, 2500 tons, which was built at Liverpool in 1853 and was at that time the largest merchant ship that had been built in England. She was a very handsome iron vessel, with three decks and large accommodation for cabin and steerage passengers. This vessel was wrecked off the coast of Ireland on her first voyage to Melbourne when only two days out from Liverpool, and became a total loss; of her 652 passengers, only 282 were saved. Among the many other vessels built in Great Britain during this period were the Lord of the Isles, already mentioned in Chapter XII; Vimiera, 1037 tons, built at Sunderland; the Contest, 1119 tons, built at Ardrossan on the Firth of Clyde; and the Gauntlet (iron), 784 tons, and Kate Carnie, 547 tons, both built at Greenock. All of these vessels were a decided improvement upon any ships hitherto built in Great Britain, and they made some fine passages, among them that of the Lord of the Isles, from the Clyde to Sydney, N. S. W., in 70 days in 1853, but the 68-day record of the Marco Polo from Liverpool to Melbourne remained unbroken.

The Marco Polo was still a favorite vessel with passengers, which goes to show what a good ship she must have been, in view of the rivalry of newer and larger clippers. She sailed from Liverpool in November, 1853, commanded by Captain Charles McDonnell, who had been her chief officer under Captain Forbes. The passengers on this voyage, on their arrival at Melbourne, subscribed for a splendid service of silver, to be presented to Captain McDonnell upon his return to England, which bore the following inscription: "Presented to Captain McDonnell, of the ship Marco Polo, as a testimonial of respect from his passengers, six hundred and sixty-six in number, for his uniform kindness and attention during his first voyage, when his ship ran from Liverpool to Port Phillip Head in seventy-two days, twelve hours, and from land to land in sixty-nine days." The Marco Polo came home in 78 days, but these were the last of her famous passages, as she drifted into the hands of captains who lacked either the ability or the energy, or perhaps both, to develop her best speed—the unfortunate fate of many a good ship.

There were at that time a number of lines and private firms engaged in the Australian trade, the best known being the White Star Line, later managed by Ismay, Imrie & Co., and James Baines & Co.'s Black Ball Line, both of Liverpool. There was keen rivalry between the two, and the Ben Nevis and Guiding Star had both been built by the White Star in hopes of lowering the record of the Marco Polo. By degrees, however, it became apparent that she was an exceptional ship, not likely to be duplicated at St. John, and also that much of her speed was due to her able commanders, while the ships built in Great Britain, though fine vessels, had not come up to the mark in point of speed or passenger accommodations. It was under these circumstances that British merchants and ship-owners began to buy and build ships for the Australian trade in the United States.

The Sovereign of the Seas had attracted much attention upon her arrival at Liverpool in 1853, and was almost immediately chartered to load for Australia in the Black Ball Line. It is to be regretted that for some reason Captain McKay gave up charge of the ship and returned to the United States, the command being given to Captain Warner, who had no previous experience in handling American clipper ships, although he proved an extremely competent commander. The Sovereign of the Seas sailed from Liverpool September 7, 1853, and arrived at Melbourne after a passage of 77 days. In a letter from Melbourne Captain Warner gives the following account of this passage:

"I arrived here after a long and tedious passage of 77 days, having experienced only light and contrary winds the greater part of the passage—I have had but two chances. The ship ran in four consecutive days 1275 miles; and the next run was 3375 miles in twelve days. These were but moderate chances. I was 31 days to the Equator, and carried skysails 65 days; set them on leaving Liverpool, and never shortened them for 35 days. Crossed the equator in 26° 30', and went to 53° 30' south, but found no strong winds. Think if I had gone to 58° south, I would have had wind enough; but the crew were insufficiently clothed, and about one half disabled, together with the first mate. At any rate, we have beaten all and every one of the ships that sailed with us, and also the famous English clipper Gauntlet ten days on the passage, although the Sovereign of the Seas was loaded down to twenty-three and one half feet." On the homeward voyage she brought the mails and over four tons of gold-dust, and made the passage in 68 days. On this voyage there was a mutiny among the crew, who intended to seize the ship and capture the treasure. Captain Warner acted with great firmness and tact in suppressing the mutineers and placing them in irons without loss of life, for which he received much credit.

The White Star Line, not to be outdone by rivals, followed the example of the Black Ball and in 1854 chartered the Chariot of Fame, Red Jacket, and Blue Jacket. These ships, of which the first was a medium clipper and the other two extreme clippers, were built in New England. The Chariot of Fame was a sister ship to the Star of Empire, 2050 tons, built by Donald McKay in 1853, for Enoch Train's Boston and Liverpool packet line. The Chariot of Fame made a number of fast voyages between England and Australia, her best passage being 66 days from Liverpool to Melbourne. The Blue Jacket as a handsome ship of 1790 tons, built by R. E. Jackson at East Boston in 1854, and was owned by Charles R. Green, of New York. Her best passages were 67 days from Liverpool to Melbourne and home in 69 days.

The Red Jacket, the most famous of this trio, was built by George Thomas at Rockland, Maine, in 1853–1854, and was owned by Seacomb & Taylor, of Boston. She registered 2006 tons; length 260 feet, breadth 44 feet, depth 26 feet; and was designed by Samuel A, Pook, of Boston, who had designed a number of other clipper ships, including the Challenger—not the English ship of that name,—the Game-Cock, Surprise, Northern Light, Ocean Chief, Fearless, Ocean Telegraph, and Herald of the Morning. He also designed several freighting vessels and yachts. It was the custom at that period for vessels to be designed in the yards where they were constructed, and Mr. Pook was the first naval architect in the United States who was not connected with a ship-bulding yard. On her first voyage the Red Jacket sailed from New York for Liverpool, February 19, 1854, commanded by Captain Asa Eldridge, and made the passage in 13 days 1 hour from Sandy Hook to the Rock Light, Liverpool, with the wind strong from southeast to westsouthwest, and either rain, snow, or hail during the entire run. During the first seven days she averaged only 182 miles per twenty-four hours, but during the last six days she made 219, 413, 374, 348, 300, and 371 miles, an average of a fraction over 353 miles per twenty-four hours.

Captain Eldridge was well known in Liverpool, having, together with his brothers, John and Oliver, commanded some of the finest New York and Liverpool packet ships of their day; he had also commanded Commodore Vanderbilt's steam yacht North Star during her cruise in European waters in 1853. He was afterwards lost in command of the steamship Pacific of the Collins Line.

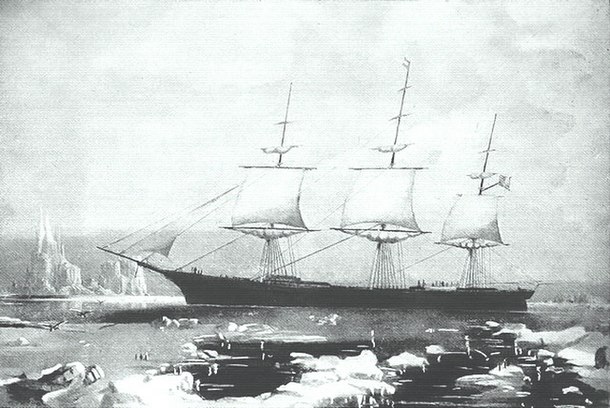

The Red Jacket attracted a great deal of attention at Liverpool, being an extremely handsome ship—quite as good-looking as any of the clippers built at New York or Boston. For a figurehead she carried a full-length representation of the Indian chief for whom she was named. She made her first voyage from Liverpool to Melbourne in 1854 under command of Captain Samuel Reed in 69 days, and as she received very quick despatch, being in port only 12 days, and made the passage to Liverpool in 73 days, the voyage round the globe, including detention in port, was made in five months and four days. On the homeward passage, bringing home 45,000 ounces of gold, she beat the celebrated Guiding Star by 9 days, though she lost considerable time through being among the bergs and field ice off Cape Horn. Upon her arrival at Liverpool the Red Jacket was sold to Pilklington & Wilson, of that port, then agents of the White Star Line, for £30,000, and continued in the Australian trade for several years, becoming one of the most famous of the American-built clippers.

The competition of the Black Ball and White Star lines proved of great benefit to both cabin and steerage passengers, as their comfort and convenience became subjects of consideration in a manner unthought of in the old days before the discovery of gold at Bendigo and Ballarat.

The "Red Jacket"