Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile/Volume 1/Book 1/Chapter 6

CHAP. VI.

Arrive at Furshout—Adventure of Friar Christopher—Visit Thebes—Luxor and Carnac—Large Ruins at Edfu and Esné—Proceed on our Voyage.

We arrived happily at Furshout that same forenoon, and went to the convent of Italian Friars, who, like those of Achmim, are of the order of the reformed Franciscans, of whose mission I shall speak at large in the sequel.

We were received more kindly here than at Achmim; but Padre Antonio, superior of that last convent, upon which this of Furshout also depends, following us, our good reception suffered a small abatement. In short, the good Friars would not let us buy meat, because they said it would be a shame and reproach to them; and they would not give us any, for fear that should be a reproach to them likewise, if it was told in Europe they lived well.

After some time I took the liberty of providing for myself, to which they submitted with christian patience. Yet these convents were founded expressly with a view, and from a necessity of providing for travellers between Egypt and Ethiopia, and we were strictly intitled to that entertainment. Indeed there is very little use for this institution in Upper Egypt, as long as rich Arabs are there, much more charitable and humane to stranger Christians than the Monks.

Furshout is in a large and cultivated plain. It is nine miles over to the foot of the mountains, all sown with wheat. There are, likewise, plantions of sugar canes. The town, as they said, contains above 10,000 people, but I have no doubt this computation is rather exaggerated.

We waited upon the Shekh Hamam; who was a big, tall, handsome man; I apprehend not far from sixty. He was dressed in a large fox-skin pelisse over the rest of his cloaths, and had a yellow India shawl wrapt about his head, like a turban. He received me with great politeness and condesension, made me sit down by him, and asked me more about Cairo than about Europe.

The Rais had told him our adventure with the saint, at which he laughed very heartily, saying, I was a wise man. and a man of conduct. To me he only said, "they are bad people at Dendera;" to which I answered, "there were very few places in the world in which there were not some bad." He replied, "Your observation is true, but there they are all bad; rest yourselves however here, it is a quiet place; though there are still some even in this place not quite so good as they ought to be."

The Shekh was a man of immense riches, and, little by little, had united in his own person, all the separate districts of Upper Egypt, each of which formerly had its particular prince. But his interest was great at Constantinople, where he applied directly for what he wanted, insomuch as to give a jealousy to the Beys of Cairo. He had in farm from the Grand Signior almost the whole country, between Siout and Syene, or Assouan. I believe this is the Shekh of Upper Egypt, whom Mr Irvine speaks of so gratefully. He was betrayed, and murdered some time after, by one of the Beys whom he had protected in his own country.

While we were at Furshout, there happened a very extraordinary phænomenon. It rained the whole night, and till about nine o'clock next morning; and the people began to be very apprehensive least the whole town should be destroyed. It is a perfect prodigy to see rain here; and the prophets said it portended a dissolution of government, which was justly verified soon afterwards, and at that time indeed was extremely probable.

Furshout is in lat 26° 3′ 30″; above that, to the southward, on the same plain, is another large village, belonging to Shekh Ismael, a nephew of Shekh Hamam. It is a large town, built with clay like Furshout, and surrounded with groves of palm trees, and very large plantations of sugar canes. Here they make sugar.

Shekh Ismael was a very pleasant and agreeable man, but in bad health, having a violent asthma, and sometimes pleuretic complaints, to be removed by bleeding only. He had given these friars a house for a convent in Badjoura; but as they had not yet taken possession of it, he desired me to come and stay there.

Friar Christopher, whom I understood to have been a Milanese barber, was his physician, but he had not the science of an English barber in surgery. He could not bleed, but with a sort of instrument resembling that which is used in cupping, only that it had but a single lancet; with this he had been lucky enough as yet to escape laming his patients. This bleeding instrument they call the Tabange, or the Pistol, as they do the cupping instrument likewise. I never could help shuddering at seeing the confidence with which this man placed a small brass box upon all sorts of arms, and drew the trigger for the point to go where fortune pleased.Shekh Ismael was very fond of this surgeon, and the surgeon of his patron; all would have gone well, had not friar Christopher aimed likewise at being an Astronomer. Above all he gloried in being a violent enemy to the Copernican system, which unluckily he had mistaken for a heresy in the church; and partly from his own slight ideas and stock of knowledge, partly from some Milanese almanacs he had got, he attempted, the weather being cloudy, to foretel the time when the moon was to change, it being that of the month Ramadan, when the Mahometans' lent, or fasting, was to begin.

It happened that the Badjoura people, and their Shekh Ismael, were upon indifferent terms with Hamam, and his men of Furshout, and being desirous to get a triumph over their neighbours by the help of their friar Christopher, they continued to eat, drink, and smoke, two days after the conjunction.

The moon had been seen the second night, by a Fakir[1], in the desert, who had sent word to Shekh Hamam, and he had begun his fast. But Ismael, assured by friar Christopher that it was impossible, had continued eating.The people of Furshout, meeting their neighbours singing and dancing, and with pipes of tobacco in their mouths, all cried out with astonishment, and asked, "Whether they had abjured their religion or not?"—From words they came to blows; seven or eight were wounded on each side, luckily none of them mortally.—Hamam next day came to inquire at his nephew Shekh Ismael, what had been the occasion of all this, and to consult what was to be done, for the two villages had declared one another infidels.

I was then with my servants in Badjoura, in great quiet and tranquillity, under the protection, and very much in the confidence of Ismael; but hearing the hooping, and noise in the streets, I had barricadoed my outer-doors. A high wall surrounded the house and court-yard, and there I kept quiet, satisfied with being in perfect safety.

In the interim, I heard it was a quarrel about the keeping of Ramadan, and, as I had provisions, water, and employment enough in the house, I resolved to stay at home till they fought it out; being very little interested which of them should be victorious.—About noon, I was sent for to Ismael's house, and found his uncle Hamam with him.

He told me, there were several wounded in a quarrel about the Ramadan, and recommended them to my care. "About Ramadan, said I! what, your principal fast! have you not settled that yet?"—Without answering me as to this, he asked, "When does the moon change?" As I knew nothing of friar Christopher's operations, I answered, in hours, minutes, and seconds, as I found them in the ephemerides."Look you there, says Hamam, this is fine work!" and, directing his discourse to me, "When shall we see it?" Sir, said I, that is impossible for me to tell, as it depends on the state of the heavens; but, if the sky is clear, you must see her to-night; if you had looked for her, probably you would have seen her last night low in the horizon, thin like a thread; she is now three days old.— He started at this, then told me friar Christopher's operation, and the consequences of it.

Ismael was ashamed, cursed him, and threatned revenge. It was too late to retract, the moon appeared, and spoke for herself; and the unfortunate friar was disgraced, and banished from Badjoura. Luckily the pleuretic stitch came again, and I was called to bleed him, which I did with a lancet; but he was so terrified at its brightness, at the ceremony of the towel and the bason, and at my preparation, that it did not please him, and therefore he was obliged to be reconciled to Christopher and his tabange.—Badjoura is in lat. 26° 3′ 16″; and is situated on the western shore of the Nile, as Furshout is likewise.

We left Furshout the 7th of January 1769, early in the morning. We had not hired our boat farther than Furshout; but the good terms which subsisted between me and the saint, my Rais, made an accommodation very easy to carry us farther. He now agreed for L.4 to carry us to Syene and down again; but, if he behaved well, he expected a trifling premium. "And, if you behave ill, Hassan, said I, what do you think you deserve?"—"To be hanged, said he, I deserve, and desire no better."Our wind at first was but scant. The Rais said, that he thought his boat did not go as it used to do, and that it was growing into a tree. The wind, however, freshened up towards noon, and eased him of his fears. We passed a large town called How, on the west side of the Nile. About four o'clock in the afternoon we arrived at El Gourni, a small village, a quarter of a mile distant from the Nile. It has in it a temple of old Egyptian architecture. I think that this, and the two adjoining heaps of ruins, which are at the same distance from the Nile, probably might have been part of the ancient Thebes.

Shaamy and Taamy are two colossal statues in a sitting posture covered with hieroglyphics. The southmost is of one stone, and perfectly entire. The northmost is a good deal more mutilated. It was probably broken by Cambyses; and they have since endeavoured to repair it. The other has a very remarkable head-dress, which can be compared to nothing but a tye-wig, such as worn in the present day. These two, situated in a very fertile spot belonging to Thebes, were apparently the Nilometers of that town, as the marks which the water has left upon the bases sufficiently shew. The bases of both of them are bare, and uncovered, to the bottom of the plinth, or lowest member of their pedestal; so that there is not the eighth of an inch of the lowest part of them covered with mud, though they stand in the middle of a plain, and have stood there certainly above 3000 years; since which time, if the fanciful rise of the land of Egypt by the Nile had been true, the earth should have been raised so as fully to conceal half of them both.

These statues are covered with inscriptions of Greek and Latin; the import of which seems to be, that there were certain travellers, or particular people, who heard Memnon's statue utter the sound it was said to do, upon being struck with the rays of the sun.

It may be very reasonably expected, that I should here say something of the building and fall of the first Thebes; but as this would carry me to very early ages, and interrupt for a long time my voyage upon the Nile; as this is, besides, connected with the history of several nations which I am about to describe, and more proper for the work of an historian, than the cursory descriptions of a traveller, I shall defer saying any thing upon the subject, till I come to treat of it in the first of these characters, and more especially till I shall speak of the origin of the shepherds, and the calamities brought upon Egypt by that powerful nation, a people often mentioned by different writers, but whose history hitherto has been but imperfectly known.

Nothing remains of the ancient Thebes but four prodigious temples, all of them in appearance more ancient, but neither so entire, nor so magnificent, as those of Dendera. The temples at Medinet Tabu are the most elegant of these. The hieroglyphics are cut to the depth of half-a-foot, in some places, but we have still the same figures, or rather a less variety, than at Dendera.

The hieroglyphics are of four sorts; first, such as have only the contour marked, and, as it were, scratched only in the stone. The second are hollowed; and in the middle of that space rises the figure in relief, so that the prominent part of the figure is equal to the flat, unwrought surface of the stone, and seems to have a frame round it, designed to defend the hieroglyphic from mutilation. The third sort is in relief, or basso relievo, as it is called, where the figure is left bare and exposed, without being sunk in, or defended, by any compartment cut round it in the stone. The fourth are those mentioned in the beginning of this description, the outlines of the figure being cut very deep in the stone.

All the hieroglyphics, but the last mentioned, which do not admit it, are painted red, blue, and green, as at Dendera, and with no other colours.

Notwithstanding all this variety in the manner of executing the hieroglyphical figures, and the prodigious multitude which I have seen in the several buildings, I never could make the number of different hieroglyphics amount to more than five hundred and fourteen, and of these there were certainly many, which were not really different, but from the ill execution of the sculpture only appeared so. From this I conclude, certainly, that it can be no entire language which hieroglyphics are meant to contain, for no language could be comprehended in five hundred words, and it is probable that these hieroglyphics are not alphabetical or single letters only; for five hundred letters would make too large an alphabet. The Chinese indeed have many more letters in use, but have no alphabet, but who is it that understands the Chinese?

There are three different characters which, I observe, have been in use at the same time in Egypt, Hieroglyphics, the Mummy character, and the Ethiopic. These are all three found, as I have seen, on the same mummy, and therefore were certainly used at the same time. The last only I believe was a language.

The mountains immediately above or behind Thebes, are hollowed out into numberless caverns, the first habitations of the Ethiopian colony which built the city. I imagine they continued long in these habitations, for I do not think the temples were ever intended but for public and solemn uses, and in none of these ancient cities did I ever see a wall or foundation, or any thing like a private house; all are temples and tombs, if temples and tombs in those times were not the same thing. But vestiges of houses there are none, whatever[2] Diodorus Siculus may say, building with stone was too expensive for individuals; the houses probably were all of clay, thatched with palm branches, as they are at this day. This is one reason why so few ruins of the immense number of cities we hear of remain.

Thebes, according to Homer, had a hundred gates. We cannot, however, discover yet the foundation of any wall that it had; and as for the horsemen and chariots it is said to have sent out, all the Thebaid sown with wheat would not have maintained one-half of them.Thebes, at least the ruins of the temples, called Medinet Tabu, are built in a long stretch of about a mile broad, most parsimoniously chosen at the sandy foot of the mountains. The Horti[3] Pensiles, or hanging gardens, were surely formed upon the sides of these hills, then supplied with water by mechanical devices. The utmost is done to spare the plain, and with great reason; for all the space of ground this ancient city has had to maintain its myriads of horses and men, is a plain of three quarters of a mile broad, between the town and the river, upon which plain the water rises to the height of four, and five feet, as we may judge by the marks on the statues Shaamy and Taamy. All this pretended populousness of ancient Thebes I therefore believe fabulous.

It is a circumstance very remarkable, in building the first temples, that, where the side-walls are solid, that is, not supported by pillars, some of these have their angles and faces perpendicular, others inclined in a very considerable angle to the horizon. Those temples, whose walls are inclined, you may judge by the many hieroglyphics and ornaments, are of the first ages, or the greatest antiquity. From which, I am disposed to think, that singular construction was a remnant of the partiality of the builders for their first domiciles; an imitation of the slope[4], or inclination of the sides of mountains, and that this inclination of flat surfaces to each other in building, gave afterwards the first idea of Pyramids[5].

A number of robbers, who much resemble our gypsies, live in the holes of the mountains above Thebes. They are all out-laws, punished with death if elsewhere found. Osman Bey, an ancient governor of Girgé, unable to suffer any longer the disorders committed by these people, ordered a quantity of dried faggots to be brought together, and, with his soldiers, took possession of the face of the mountain, where the greatest number of these wretches were: He then ordered all their caves to be filled with this dry brushwood, to which he set fire, so that most of them were destroyed; but they have since recruited their numbers, without changing their manners.

About half a mile north of El Gourni, are the magnificent, stupendous sepulchres, of Thebes. The mountains of the Thebaid come close behind the town; they are not run in upon one another like ridges, but stand insulated upon their bases; so that you can get round each of them. A hundred of these, it is said, are excavated into sepulchral, and a variety of other apartments. I went through seven of them with a great deal of fatigue. It is a solitary place; and my guides, either from a natural impatience and distaste that these people have at such employments, or, that their fears of the banditti that live in the caverns of the mountains were real, importuned me to return to the boat, even before I had begun my search, or got into the mountains where are the many large apartments of which I was in quest.

In the first one of these I entered is the prodigious sarcophagus, some say of Menes, others of Osimandyas; possibly of neither. It is sixteen feet high, ten long, and six broad, of one piece of red-granite; and, as such, is, I suppose, the finest vase in the world. Its cover is still upon it, (broken on one side,) and it has a figure in relief on the outside. It is not probably the tomb of Osimandyas, because, Diodorus[6] says, that it was ten stadia from the tomb of the kings; whereas this is one among them.

There have been some ornaments at the outer-pillars, or outer-entry, which have been broken and thrown down. Thence you descend through an inclined passage, I suppose, about twenty feet broad; I speak only by guess, for I did not measure. The side-walls, as well as the roof of this passage, are covered with a coat of stucco, of a finer and more equal grain, or surface, than any I ever saw in Europe. I found my black-lead pencil little more worn by it than by writing upon paper. Upon the left-hand side is the crocodile seizing upon the apis, and plunging him into the water. On the right-hand is the [7]scarabæus thebaicus, or the thebaic beetle, the first animal that is seen alive after the Nile retires from the land; and therefore thought to be an emblem of the resurrection. My own conjecture is, that the apis was the emblem of the arable land of Egypt; the crocodile, the typhon, or cacodæmon, the type of an over-abundant Nile; that the scarabæus was the land which had been overflowed, and from which the water had soon retired, and has nothing to do with the resurrection or immortality, neither of which at that time were in contemplation.

Farther forward on the right-hand of the entry, the pannels, or compartments, were still formed in stucco, but, in place of figures in relief, they were painted in fresco. I dare say this was the case on the left-hand of the passage, as well as the right. But the first discovery was so unexpected, and I had flattered myself that I should be so far master of my own time, as to see the whole at my leisure, that I was rivetted, as it were, to the spot by the first sight of these paintings, and I could proceed no further.

In one pannel were several musical instruments strowed upon the ground, chiefly of the hautboy kind, with a mouthpiece of reed. There were also some simple pipes or flutes. With them were several jars apparently of potter-ware, which, having their mouths covered with parchment or skin, and being braced on their sides like a drum, were probably the instrument called the tabor, or [8]tabret, beat upon by the hands, coupled in earliest ages with the harp, and preserved still in Abyssinia, though its companion, the last-mentioned instrument, is no longer known there.

In three following pannels were painted, in fresco, three harps, which merited the utmost attention, whether we consider the elegance of these instruments in their form, and the detail of their parts as they are here clearly expressed, or confine ourselves to the reflection that necessarily follows, to how great perfection music must have arrived, before an artist could have produced so complete an instrument as either of these.

As the first harp seemed to be the most perfect, and least spoiled, I immediately attached myself to this, and desired my clerk to take upon him the charge of the second. In this way, by sketching exactly, and loosely, I hoped to have made myself master of all the paintings in that cave, perhaps to have extended my researches to others, though, in the sequel, I found myself miserably deceived.

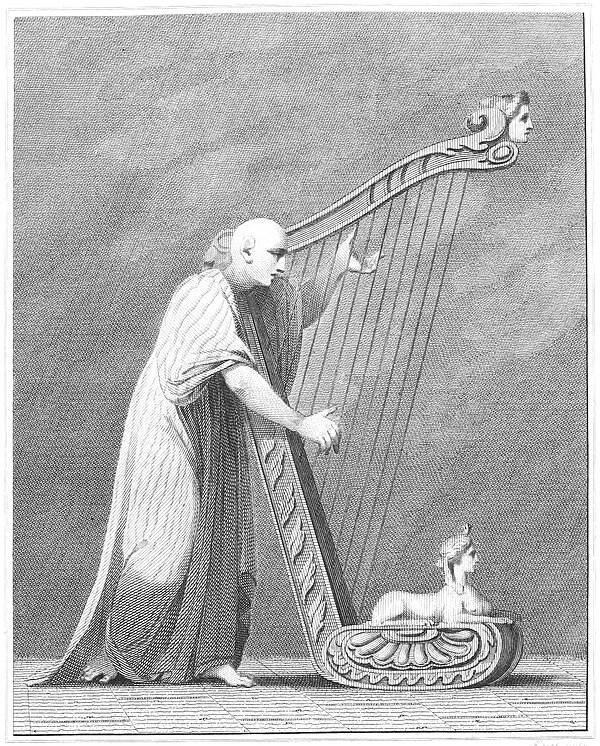

My first drawing was that of a man playing upon a harp; he was standing, and the instrument being broad, and flat at the base, probably for that purpose, supported itself easily with a very little inclination upon his arm; his head is close shaved, his eye-brows black, without beard or mus

Painting in Fresco, in the Sepulchres of Thebes. tachoes. He has on him a loose shirt, like what they wear at this day in Nubia (only it is not blue) with loose sleeves, and arms and neck bare. It seemed to be thick muslin, or cotton cloth, and long-ways through it is a crimson stripe about one-eighth of an inch broad; a proof, if this is Egyptian manufacture, that they understood at that time how to dye cotton, crimson, an art found out in Britain only a very few years ago. If this is the fabric of India, still it proves the antiquity of the commerce between the two countries, and the introduction of Indian manufactures into Egypt.

It reached down to his ancle; his feet are without sandals; he seems to be a corpulent man, of about sixty years of age, and of a complexion rather dark for an Egyptian. To guess by the detail of the figure, the painter seems to have had the same degree of merit with a good sign-painter in Europe, at this day.—If we allow this harper's stature to be five feet ten inches, then we may compute the harp, in its extreme length, to be something less than six feet and a half.

This instrument is of a much more advantageous form than the triangular Grecian harp. It has thirteen strings, but wants the forepiece of the frame opposite to the longest string. The back part is the sounding-board, composed of four thin pieces of wood, joined together in form of a cone, that is, growing wider towards the bottom; so that, as the length of the string increases, the square of the corresponding space in the sounding-board, in which the sound was to undulate, always increases in proportion. The whole principles, on which this harp is constructed, are rational and ingenious, and the ornamented parts are executed in the very best manner.

The bottom and sides of the frame seem to be fineered, and inlaid, probably with ivory, tortoise-shell, and mother-of-pearl, the ordinary produce of the neighbouring seas and deserts. It would be even now impossible, either to construct or to finish a harp of any form with more taste and elegance. Besides the proportions of its outward form, we must observe likewise how near it approached to a perfect instrument, for it wanted only two strings of having two complete octaves; that these were purposely omitted, not from defect of taste or science, must appear beyond contradiction, when we consider the harp that follows.

I had no sooner finished the harp which I had taken in hand, than I went to my assistant, to see what progress he had made in the drawing in which he was engaged. I found, to my very great surprise, that this harp differed essentially, in form and distribution of its parts, from the one I had drawn, without having lost any of its elegance; on the contrary, that it was finished with full more attention than the other. It seemed to be fineered with the same materials, ivory and tortoise-shell, but the strings were differently disposed, the ends of the three longest, where they joined to the sounding-board below, were defaced by a hole dug in the wall. Several of the strings in different parts had been scraped as with a knife, for the rest it was very perfect. It had eighteen strings. A man, who seemed to be still older than the former, but in habit perfectly the same, bare-footed, close shaved, and of the same complexion with him, stood Painting in Fresco, in the Sepulchres of Thebes.

London Published Dec.r 1.st 1789 by G. Robinson & Co. playing with both his hands near the middle of the harp, in a manner seemingly less agitated than in the other.

I went back to my first harp, verified, and examined my drawing in all its parts; it is with great pleasure I now give a figure of this second harp to the reader, it was mislaid among a multitude of other papers, at the time when I was solicited to communicate the former drawing to a gentleman then writing the History of Music, which he has already submitted to the public; it is very lately and unexpectedly this last harp has been found; I am only sorry this accident has deprived the public of Dr Burney's remarks upon it. I hope he will yet favour us with them, and therefore abstain from anticipating his reflections, as I consider this as his province; I never knew any one so capable of affording the public, new, and at the same time just lights on this subject.

There still remained a third harp of ten strings, its precise form I do not well remember, for I had seen it but once when I first entered the cave, and was now preparing to copy that likewise. I do not recollect, that there was any man playing upon this one, I think it was rather resting upon a wall, with some kind of drapery upon one end of it, and was the smallest of the three. But I am not at all so certain of particulars concerning this, as to venture any description of it; what I have said of the other two may be absolutely depended upon.

I look upon these harps then as the Theban harps in use in the time of Sesostris, who did not rebuild, but decorate ancient Thebes; I consider them as affording an incontestible proof, were they the only monuments remaining, that every art necessary to the construction, ornament, and use of this instrument, was in the highest perfection, and if so, all the others must have probably attained to the same degree.

We see in particular the ancients then possessed an art relative to architecture, that of hewing the hardest stones with the greatest ease, of which we are at this day utterly ignorant and incapable. We have no instrument that could do it, no composition that could make tools of temper sufficient to cut bass reliefs in granite or porphyry so readily; and our ignorance in this is the more completely shewn, in that we have all the reasons to believe, the cutting instrument with which they did these surprising feats was composed of brass; a metal of which, after a thousand experiments, no tool has ever been made that could serve the purpose of a common knife, though we are at the same time certain, it was of brass the ancients made their razors.

These harps, in my opinion, overturn all the accounts hitherto given of the earliest state of music and musical instruments in the east; and are altogether in their form, ornaments, and compass, an incontestible proof, stronger than a thousand Greek quotations, that geometry, drawing, mechanics, and music, were at the greatest perfection when this instrument was made, and that the period from which we date the invention of these arts, was only the beginning of the æra of their restoration. This was the sentiment of Solomon, writer who lived at the time when this harp was painted: "Is there (says Solomon) any thing whereof it may be said, "See, this is new! it hath been already of old time which was before us *[9]."

We find, in these very countries, how a later calamity, of the same public nature, the conquest of the Saracens, occasioned a similar downfal of literature, by the burning the Alexandrian library under the fanatical caliph Omar. We see how soon after, they flourished, planted by the same hands that before had rooted them out.

The effects of a revolution occasioned, at the period I am now speaking of, by the universal inundation of the Shepherds, were the destruction of Thebes, the ruin of architecture, and the downfal of astronomy in Egypt. Still a remnant was left in the colonies and correspondents of Thebes, though fallen. Ezekiel †[10] celebrates Tyre as being, from her beginning, famous for the tabret and harp, and it is probably to Tyre the taste for music fled from the contempt and persecution of the barbarous Shepherds; who, though a numerous nation, to this day never have yet possessed any species of music, or any kind of musical instruments capable of improvement.

Although it is a curious subject for reflection, it should not surprise us to find here the harp, in such variety of form. Old Thebes, as we presently shall see, had been destroyed, and was soon after decorated and adorned, but not rebuilt by Sesostris. It was some time between the reign of Menes, the first king of the Thebaid, and the first general war of the Shepherds, that these decorations and paintings were made. This gives it a prodigious antiquity; but supposing it was a favourite instrument, consequently well understood at the building of Tyre *[11] in the year 1320 before Christ, and Sesostris had lived in the time of Solomon, as Sir Isaac Newtoni magines; still there were 320 years since that instrument had already attained to great perfection, a sufficient time to have varied it into every form.

Upon seeing the preparations I was making to proceed farther in my researches, my conductors lost all sort of subordination. They were afraid my intention was to sit in this cave all night, (as it really was,) and to visit the others next morning. With great clamour and marks of discontent, they dashed their torches against the largest harp, and made the best of their way out of the cave, leaving me and my people in the dark; and all the way as they went, they made dreadful denunciations of tragical events that were immediately to follow, upon their departure from the cave.

There was no possibility of doing more. I offered them money, much beyond the utmost of their expectations; but the fear of the Troglodytes, above Medinet Tabu, had fallen upon them ; and seeing at last this was real, I was not myself without apprehensions, for they were banditti, and outlaws, and no reparation was to be expected, whatever they should do to hurt us. Very much vexed, I mounted my horse to return to the boat. The road lay through a very narrow valley, the sides of which were covered with bare loose stones. I had no sooner got down to the bottom, than I heard a great deal of loud speaking on both sides of the valley; and, in an instant, a number of large stones were rolled down upon me, which, though I heard in motion, I could not see, on account of the darkness; this increased my terror.

Finding, by the impatience of the horse, that several of these stones had come near him, and that it probably was the noise of his feet which guided those that threw them, I dismounted, and ordered the Moor to get on horseback; which he did, and in a moment galloped out of danger. This, if I had been wise, I certainly might have done before him, but my mind was occupied by the paintings. Nevertheless, I was resolved upon revenge before leaving these banditti, and listened till I heard voices, on the right side of the hill. I accordingly levelled my gun as near as possible, by the ear, and fired one barrel among them. A moment's silence ensued, and then a loud howl, which seemed to have come from thirty or forty persons. I took my servant's blunderbuss, and discharged it where I heard the howl, and a violent confusion of tongues followed, but no more stones. As I found this was the time to escape, I kept along the dark side of the hill, as expeditiously as possible, till I came to the mouth of the plain, when we reloaded our firelocks, expecting some interruption before we reached the boat; and then we made the best of our way to the river. We found our Rais full of fears for us. He had been told, that, as soon as day light should appear, the whole Troglodytes were to come down to the river, in order to plunder and destroy our boat.

This night expedition at the mountains was but partial, the general attack was reserved for next day. Upon holding council, we were unanimous in opinion, as indeed we had been during the whole course of this voyage. We thought, since our enemy had left us to-night, it would be our fault if they found us in the morning. Therefore, without noise, we cast off our rope that fastened us, and let ourselves over to the other side. About twelve at night a gentle breeze began to blow, which wafted us up to Luxor, where there was a governor, for whom I had letters.

From being convinced by the sight of Thebes, which had not the appearance of ever having had walls, that the fable of the hundred gates, mentioned by Homer, was mere invention, I was led to conjecture what could be the origin of that fable.

That the old inhabitants of Thebes lived in caves in the mountains, is, I think, without doubt, and that the hundred mountains I have spoken of, excavated, and adorned, were the greatest wonders at that time, seems equally probable. Now, the name of these to this day is Beeban el Meluke, the ports or gates of the kings, and hence, perhaps, come the hundred gates of Thebes upon which the Greeks have dwelt so much. Homer never saw Thebes, it was demolished before the days of any profane writer, either in prose or verse. What he added to its history must have been from imagination. All that is said of Thebes, by poets or historians, after the days of Homer, is meant of Diospolis; which was built by the Greeks long after Thebes was destroyed, as its name testifies; though Diodorus *[12] says it was built by Busiris. It was on the east side of the Nile, whereas ancient Thebes was on the west, though both are considered as one city and †[13]Strabo says, that the river ‡[14] runs through the middle of Thebes, by which he means between old Thebes and Diospolis, or Luxor and Medinet Tabu.

While in the boat, I could not help regretting the time I had spent in the morning, in looking for the place in the narrow valley where the mark of the famous golden circle was visible, which Norden says he saw, but I could discern no traces of it any where, and indeed it does not follow that the mark left was that of a circle. This magnificent instrument was probably fixed perpendicular to the horizon in the plane of the meridian; so that the appearance of the place where it stood, would very probably not partake of the circular form at all, or any precise shape whereby to know it. Besides, as I have before said, it was not among these tombs or excavated mountains, but ten stades from them, so the vestiges of this famous instrument §[15] could not be found here. Indeed, being omitted in the lateft edition of Norden, it would seem that traveller himself was not perfectly well assured of its existence. We were well received by the governor of Luxor, who was also a believer in judicial astrology. Having made him a small present, he furnished us with provisions,- and, among several other articles, some brown sugar; and as we had seen limes and lemons in great perfection at Thebes, we were resolved to refresh ourselves with some punch, in remembrance of Old England. But, after what had happened the night before, none of our people chose to run the risk of meeting the Troglodytes. We therefore procured a servant of the governor's of the town, to mount upon his goat-skin filled with wind, and float down the stream from Luxor to El Gournie, to bring us a supply of these, which he soon after did.

He informed us, that the people in the caves had, early in the morning, made a descent upon the townsmen, with a view to plunder our boat; that several of them had been wounded the night before, and they threatened to pursue us to Syene. The servant did all he could to frighten them, by saying that his master's intention was to pass over with troops, and exterminate them, as Osman Bey of Girgé had before done, and we were to assist him with our fire-arms. — After this we heard no more of them.

Luxor, and Carnac, which is a mile and a quarter below it, are by far the largest and most magnificent scenes of ruins in Egypt, much more extensive and stupendous than those of Thebes and Dendera put together.

There are two obelisks here of great beauty, and in good preservation, they are less than those at Rome, but not at all mutilated. The pavement, which is made to receive the shadow, is to this day so horizontal, that it might still be used in observation. The top of the obelisk is semicircular, an experiment, I suppose, made at the instance of the observer, by varying the shape of the point of the obelisk, to get rid of the penumbra.

At Carnac we saw the remains of two vast rows of sphinxes, one on the right-hand, the other on the left, (their heads were mostly broken) and, a little lower, a number of termini as it should seem. They were composed of basaltes, with a dog or lion's head, of Egyptian sculpture. They stood in lines likewise, as if to conduct or serve as an avenue to some principal building.

They had been covered with earth, till very lately a *[16] Venetian physician and antiquary bought one of them at a very considerable price, as he said, for the king of Sardinia. This has caused several others to be uncovered, though no purchaser hath yet offered.

Upon the outside of the walls at Carnac and Luxor there seems to be an historical engraving instead of hieroglyphics; this we had not met with before. It is a representation of men, horses, chariots, and battles; some of the attitudes are freely and well drawn, they are rudely scratched upon the surface of the stone, as some of the hieroglyphics at Thebes are. The weapons the men make use of are short javelins, such as are common at this day among the inhabitants of Egypt, only they have feathered wings like arrows. There is also distinguished among the rest, the figure of a man on horseback, with a lion fighting furiously by him, and Diodorus *[17] says, Osimandyas was so represented at Thebes. This whole composition merits great attention..

I have said, that Luxor is Diospolis, and should think, that that place, and Carnac together, made the Jovis Civitas Magna of Ptolemy, though there is 9' difference of the latitude by my observation compared with his. But as mine was made on the south of Luxor, if his was made on the north of Carnac, the difference will be greatly diminished.

The 17th we took leave of our friendly Shekh of Luxor, and sailed with a very fair wind, and in great spirits. The liberality of the Shekh of Luxor had extended as far as even to my Rais, whom he engaged to land me here upon my return. — I had procured him considerable ease in some complaints he had; and he saw our departure with as much regret as in other places they commonly did our arrival.

On the eastern shore are Hambdé, Maschergarona, Tot, Senimi, and Gibeg. Mr Norden seems to have very much confused the places in this neighbourhood, as he puts Erment opposite to Carnac, and Thebes farther south than Erment, and on the east side of the Nile, whilst he places Luxor farther south than Erment. But Erment is fourteen miles farther south than Thebes, and Luxor about a quarter of a mile (as I have already said) farther south on the East side of the river, whereas Thebes is on the West.

He has fixed a village (which he calls *[18] Demegeit) in the situation where Thebes stands, and he calls it Crocodilopolis, from what authority I know not; but the whole geography is here exceedingly confused, and out of its proper position.

In the evening we came to an anchor on the eastern shore nearly opposite to Esné. Some of our people had landed to shoot, trusting to a turn of the river that is here, which would enable them to keep up with us; but they did not arrive till the sun was setting, loaded with hares, pigeons, gootos, all very bad game. I had, on my part, staid on board, and had shot two geese, as bad eating as the others, but very beautiful in their plumage.

We passed over to Esné next morning. It is the ancient Latopolis, and has very great remains, particularly a large temple, which, though the whole of it is of the remotest antiquity, seems to have been built at different times; or rather out of the ruins of different ancient buildings. The hieroglyphics upon this are very ill executed, and are not painted The town is the residence of an Arab Shekh, and the inhabitants are a very greedy, bad sort of people; but as I was dressed like an Arab, they did not molest, because they did not know me.

The 18th, we left Esné, and passed the town of Edfu, where there is likewise considerable remains of Egyptian architecture. It is the Appollinis Civitas Magna. The wind failing, we were obliged to stop in a very poor, desolate, and dangerous part of the Nile, called Jibbel el Silfelly, where a boom, or chain, was drawn across the river, to hinder, as is supposed, the Nubian boats from committing piratical practices in Egypt lower down the stream. The stones on both sides, to which the chain was fixed, are very visible; but I imagine that it was for fiscal rather than for warlike purposes, for Syene being garrisoned, there is no possibility of boats passing from Nubia by that city into Egypt. There is indeed another purpose to which it might be designed; to prevent war upon the Nile between any two states.

We know from Juvenal *[19], who lived some time at Syene, that there was a tribe in that neighbourhood called Ombi, who had violent contentions with the people of Dendera about the crocodile; it is remarkable these two parties were Anthropophagi so late as Juvenal's time, yet no historian speaks of this extraordinary fact, which cannot be called in question, as he was an eye-witness and resided at Syene.

Now these two nations who were at war had above a hundred miles of neutral territory between them, and therefore they could never meet except on the Nile. But either one or the other possessing this chain, could hinder his adversary from coming nearer him. As the chain is in the hermonthic nome, as well as the capital of the Ombi, I suppose this chain to be the barrier of this last state, to hinder those of Dendera from coming up the river to eat them.

About noon we passed Coom Ombo, a round building like a castle, where is supposed to have been the metropolis of Ombi, the people last spoken of. We then arrived at Daroo *[20], a miserable mansion, unconscious that, some years after we were to be indebted to that paltry village for the man who was to guide us through the desert, and restore us to our native country and our friends.

We next came to Shekh Ammer, the encampment of the Arabs †[21] Ababdé, I suppose the same that Mr Norden calls Ababuda, who reach from near Coffeir far into the desert. As I had been acquainted with one of them at Badjoura, who desired medicines for his father, I promised to call upon him, and see their effect, when I should pass Shekh Ammer, which I now accordingly did; and by the reception I met with, I found they did not expect I would ever have been as good as my word. Indeed they would probably have been in the right, but as I was about to engage myself in extensive deserts, and this was a very considerable nation in these tracts, I thought it was worth my while to put myself under their protection.

Shekh Ammer is not one, but a collection of villages, composed of miserable huts, containing, at this time, about a thousand effective men: they possess few horse, and are mostly mounted on camels. These were friends to Shekh Hamam, governor of Upper Egypt for the time, and consequently to the Turkish government at Syene, as also to the janissaries there at Deir and Ibrim. They were the barrier, or bulwark, against the prodigious number of Arabs, the Bishareen *[22], and others, depending upon the kingdom of Sennaar.

Ibrahim, the son, who had seen me at Furshout and Badjoura, knew me as soon as I arrived, and, after acquainting his father, came with about a dozen of naked attendants, with lances in their hands to escort me. I was scarce got into the door of the tent, before a great dinner was brought after their custom; and, that being dispatched, it was a thousand times repeated, how little they expected that I would have thought or inquired about them.

We were introduced to their Shekh, who was sick, in a corner of a hut, where he lay upon a carpet, with a cushion under his head. This chief of the Ababdé, called Nimmer, i. e. the Tiger (though his furious qualities were at this time in great measure allayed by sickness) asked me much about the state of Lower Egypt. I satisfied him as far as possible, but recommended to him to confine his thoughts nearer home, and not to be over anxious about these distant countries, as he himself seemed, at that time, to be in a declining state of health.

Nimmer was a man about sixty years of age, exceedingly tormented with the gravel, which was more extraordinary as he dwelt near the Nile; for it is, universally, the disease with those who use water from draw-wells, as in the desert. But he told me, that, for the first twenty-seven years of his life, he never had seen the Nile, unless upon some plundering party; that he had been constantly at war with the people of the cultivated part of Egypt, and reduced them often to the state of starving; but now that he was old, a friend to Shekh Hamam, and was resident near the Nile, he drank of its water, and was little better, for he was already a martyr to the disease. I had sent him soap pills from Badjoura, which had done him a great deal of good, and now gave him lime-water, and promised him, on my return, to shew his people how to make it.

A very friendly conversation ensued, in which was repeated often, how little they expected I would have visited them! As this implied two things; the first, that I paid no regard to my promise when given; the other, that I did not esteem them of consequence enough to give myself the trouble, I thought it right to clear myself from these suspicions.

"Shekh Nimmer, said I, this frequent repetition that you thought I would not keep my word is grievous to me. I am a Christian, and have lived now many years among you Arabs. Why did you imagine that I would not keep my word, since it is a principle among all the Arabs I have lived with, inviolably to keep theirs? When your son Ibrahim came to me at Badjoura, and told me the pain that you was in, night and day, fear of God, and desire to do good, even to them I had never seen, made me give you those medicines that have eased you. After this proof of my humanity, what was there extraordinary in my coming to see you in the way? I knew you not before ; but "my religion teaches me to do good to all men, even to enemies, without reward, or without considering whether I ever should see them again."

"Now, after the drugs I sent you by Ibrahim, tell me, and tell me truly, upon the faith of an Arab, would your people, if they met me in the desert, do me any wrong, more than now, as I have eat and drank with you to-day?"

The old man Nimmer, on this rose from his carpet, and sat upright, a more ghastly and more horrid figure I never saw. "No, said he, Shekh, cursed be those men of my people, or others, that ever shall lift up their hand against you, either in the Desert or the Tell, i.e. the part of Egypt which is cultivated. As long as you are in this country, or between this and Cosseir, my son shall serve you with heart and hand; one night of pain that your medicines freed me from, would not be repaid, if I was to follow you on foot to Messir, that is Cairo."

I then thought it a proper time to enter into conversation about penetrating into Abyssinia that way, and they discussed it among themselves in a very friendly, and at the same time in a very sagacious and sensible manner.

"We could carry you to El Haimer, (which I understood to be a well in the desert, and which I afterwards was much better acquainted with to my sorrow.) We could conduct you so far, says old Nimmer, under God, without fear of harm, all that country was Christian once, and we Christians like yourself *[23]. The Saracens having nothing in their power there, we could carry you safely to Suakem, but the Bishary are men not to be trusted, and we could go no farther than to land you among them, and they would put you to death, and laugh at you all the time they were tormenting you †[24]. Now, if you want to visit Abyssinia, go by Cosseir and Jidda, there you Christians command the country."

"I told him, I apprehended, the Kennouss, about the second cataract, above Ibrim, were bad people. He said the Kennouss were, he believed, bad enough in their hearts, but they were wretched slaves, and servants, had no power in their hands, would not wrong any body that was with his people; if they did, he would extirpate them in a day."

"I told him, I was satisfied of the truth of what was said, and asked him the best way to Cosseir. He said, the best way for me to go, was from Kenné, or Cuft, and that he was carrying a quantity of wheat from Upper Egypt, while Shekh Hamam was sending another cargo from his country, both which would be delivered at Cosseir, and loaded there for Jidda."

"All that is right, Shekh, said I, but suppose your people meet us in the desert, in going to Cosseir, or otherwise, how should we fare in that case? Should we fight?" "I have told you Shekh already, says he, Cursed be the man who lifts his hand against you, or even does not defend and befriend you, to his own loss, were it Ibrahim my own son."

I then told him I was bound to Cosseir, and that if I found myself in any difficulty, I hoped, upon applying to his people, they would protect me, and that he would give them the word, that I was yagoube, a physician, seeking no harm, but doing good; bound by a vow, for a certain time, to wander through deserts, from fear of God, and that they should not have it in their power to do me harm.

The old man muttered something to his sons in a dialect I did not then understand; it was that of the Shepherds of Suakem. As that was the first word he spoke, which I did not comprehend, I took no notice, but mixed some lime-water in a large Venetian bottle that was given me when at Cairo full of liqueur, and which would hold about four quarts; and a little after I had done this the whole hut was filled with people.

There were priests and monks of their religion, and the heads of families, so that the house could not contain half of them. The great people among them came, and, after joining hands, repeated a kind of *[25] prayer, of about two minutes long, by which they declared themselves, and their children, accursed, if ever they lifted their hands against me in the Tell, or Field in the desert, or on the river; or, in case that I, or mine should fly to them for refuge, if they did not protect us at the risk of their lives, their families, and their fortunes, or, as they emphatically expressed it, to the death of the last male child among them.

Medicines and advice being given on my part, faith and protection pledged on theirs, two bushels of wheat and seven sheep were carried down to the boat, nor could we decline their kindness, as refusing a present in that country (however it is understood in ours,) is just as great an affront, as coming into the presence of a superior without a present at all.

I told them, however, that I was going up among Turks who were obliged to maintain me, the consequence therefore will be, to save their own, that they will take your sheep, and make my dinner of them; you and I are Arabs and know what Turks are. They all muttered curses between their teeth at the name of Turk, and we agreed they should keep the sheep till I came back, provided they should be then at liberty to add as many more.

This was all understood between us, and we parted perfectly content with one another. But our Rais was very far from being satisfied, having heard something of the seven sheep; and as we were to be next day at Syene, where he knew we were to get meat enough, he reckoned that they would have been his property. To stifle all cause of discontent, however, I told him he was to take no notice of my visit to Shekh Ammer, and that I would make him amends when I returned.

- ↑ A poor saint.

- ↑ Diod. Sic. lib. I.

- ↑ Plin. lib. 26. cap. 14.

- ↑ See Norden's views of the Temples at Efné and Edfu. Vol. ii. plate 6. p. 80.

- ↑ This inclined figure of the sides, is frequently found in the small boxes within the mummy-chests.

- ↑ Diod. Sic. lib. 1.

- ↑ See the figure of this Insect in Paul Lucas.

- ↑ Gen. xxxi. 27. Isa. chap. xxx. ver. 32.

- ↑ * Eccles. chap. i. ver. 10.

- ↑ † Ezek. chap. xxviii. ver. 13.

- ↑ * Nay, prior to this, the harp is mentioned as a common instrument in Abraham's time 1370 years before Christ, Gen. chap. xxxii. ver. 27.

- ↑ * Diod. Sic. Bib. lib. i. p. 42. § d.

- ↑ † Strabo, lib. 17. p. 943.

- ↑ ‡ Nah. ch. 3. ver. 8, & 9.

- ↑ § A similar instrument, erected by Eratosthenes at Alexandria, cut of copper, was used by Hipparchus and Ptolemy. — Alm. lib. I. cap. II. 3. cap. 2. Vide his remarks on Mr Greave's Pyramidographia, p. 134.

- ↑ * Signior Donati.

- ↑ * Diod. Sic. Bib. lib. I. p. 45. § c.

- ↑ * Vide Norden's map of the Nile.

- ↑ * Juven. Sat. 15. ver. 76.

- ↑ * Idris Welled Hamran, our guide through the great desert, dwelt in this village.

- ↑ † The ancient Adei.

- ↑ * The Bishareen are the Arabs who live in the frontier between the two nations. They are the nominal subjects of Senaar, but, in fact, indiscreet banditti, at least as to strangers.

- ↑ * They were Shepherds Indigenæ, not Arabs.

- ↑ † Qui Ludit in Hospite sixo — Was a character long ago given to the Moors. Horace Ode.

- ↑ * This kind of oath was in use among the Arabs, or Shepherds, early as the time of Abraham, Gen. xxi. 22, 23. xxvi. 28.