APPENDICES

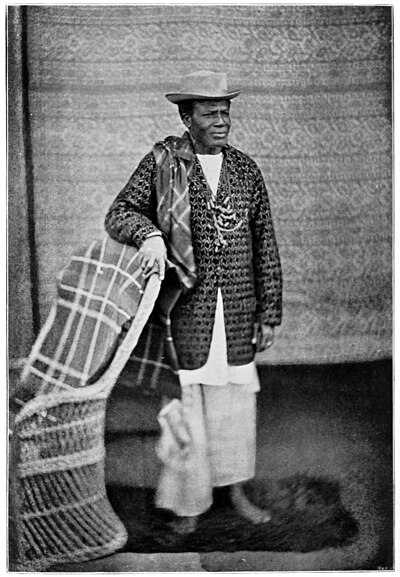

Ja Ja, King of Opobo.

APPENDIX I

It is with some diffidence I attempt this task, because many more able men have written about this country, with whom occasionally I shall most likely be found not quite in accord; but if a long residence in and connection with a country entitles one to be heard, then I am fully qualified, for I first went to Western Africa in 1862, and my last voyage was in 1896.

Previous to 1891, the date at which this Coast (Benin to Old Calabar) was formed into a British Protectorate under the name of the Oil Rivers Protectorate, now the Niger Coast Protectorate, each of the rivers frequented by Europeans for the purpose of trade was ruled over more or less intelligently by one, and in some cases by two, sable potentates, who were responsible to Her Britannic Majesty's Consul for the safety and well-being of the white traders; also for the fostering of trade in the hinterlands of their district, for which good offices they were paid by the white traders a duty called "comey," which amounted to about 2s. 6d. per ton on the palm oil exported. When the palm kernel trade commenced it was generally arranged that two tons of palm kernels should be counted to equal one ton of palm oil so far as regards fiscal arrangements. The day this duty was paid was looked upon by the king, or kings if there were two of them, as a festival; in earlier years a certain amount of ceremony was also observed.

The king would arrive on board the trader's hulk or sailing ship (some firms doing their trade without the assistance of a hulk) to an accompaniment of war horns, drums, and other savage music. With the king would generally come one or two of his chiefs and his Ju-Ju man, but before mounting the gangway ladder a bottle of spirit or palm wine would be produced from some hidden receptacle, one of the small boys, who always follow the kings or chiefs to carry their handkerchiefs and snuff-boxes, would then draw the cork and hand a wine-glass and the bottle to the Ju-Ju man, who would pour himself out a glass, saying a few words to the Ju-Ju of the river, at the same time spilling a little of the liquor into the water; he would then drink up what remained in the glass, hand glass and bottle to the king, who would then proceed as the Ju-Ju man had done, being followed on the same lines by the chiefs who were with him.

Their devotions having thus been duly attended to, the king, Ju-Ju man and his attendant chiefs would mount the ladder to the deck of the vessel. The European trader would, as a rule, be there to receive him and escort him on to the poop, where the king would be asked to sit down to a sumptuous repast of pickled pork, salt beef, tinned salmon, pickles and cabin biscuits. There would be also roast fowls and goat for the trader and his assistants, and for vegetables yams and potatoes, the latter a great treat for the white men, but not thought much of by the natives.

The king with his friends making terrific onslaughts on the pork, beef and tinned salmon, after having eaten all they could would ask for more, and pile up a plate of beef, pork and salmon, if there was any left, to pass out to their attendants on the main deck, at the same time begging some biscuits for their pull-away boys in the canoe, a request always acceded to.

Drinkables, you will observe, so far have had no part in the feed; it is because these untutored natives follow Nature's laws much closer than Europeans, and never drink until they have finished eating. The king, having done justice to the victuals, now politely intimates to the European trader that "he be time for wash mouth." Being asked what his sable majesty would like to do it in, he generally elects "port win," as the natives call port wine. His chiefs, not being such connoisseurs as his majesty, are, as a rule, satisfied with a bottle or two of beer or gin, carefully sticking to the empty bottles.

In the meantime, had you looked over the side of the ship, you would have wondered what his majesty's forty or fifty canoe boys were doing, so carefully divesting themselves of every rag of cloth and hiding it by folding it up as small as possible and sitting on it. This was so as to point out to the trader, when he came to the gangway to see the king away, that "he no be proper for king's boys no have cloth."

The king, having duly washed his mouth, is now ready to proceed with the business of his visit. The payment of the comey is very soon arranged, it being a settled sum and the different goods having their recognised value in pawns, bars, coppers or crues according to the currency of the particular river.

But the "shake hand"[1] is now to be got through, and the "dashing"[2] to the king; his friends who are with him want their part, and it would surprise a stranger the number of wants that seem to keep cropping up in a West African king's mind as he wobbles about your ship, until, finding he has begged every mortal thing that he can, he suddenly makes up his mind that further importunity will be useless; he decides to order his people into his canoe, which in most cases they obey with surprising alacrity, brought about, I have no doubt, by the thought that now comes their turn.

Arrived at the gangway, his majesty, in the most natural way imaginable, notices for the first time (?) that his boys are all naked, and turning with an appealing look to the trader, he points out the bareness of the royal pull-away boys, and intimates that no white trader who respects himself could think of allowing such a state of things to continue a moment longer. This meant at least a further dash of four dozen fishermen's striped caps and about twelve pieces of Manchester cloth.

One would suppose that this was the last straw, but before his majesty gets into his canoe several more little wants crop up, amongst others a tot of rum each for his canoe boys, and perchance a few fathoms of rope to make a new painter for his canoe, until sometimes the white trader almost loses his temper. I have heard of one (?) who did on one occasion, and being an Irishman, he thus apostrophised one of these sable kings, "Be jabers, king, I am thinking if I dashed you my ship you would be after wanting me to dash you the boats belonging to her, and after that to supply you with paint to paint them with for the next ten years." There was a glare in that Irishman's eye, and that king noticed it, and decided the time had come for him to scoot, and history says he scooted. In the early days of the palm oil trade, the custom inaugurated by the slave traders of receiving the king on his visit to the ship was by a salute of six or seven guns, and another of equal number on his departure, the latter being an intimation to all whom it might concern that his majesty had duly received his comey, and that trade was open with the said ship. This was continued for some years, but as the security of the seas became greater in those parts the trading ships gave up the custom of carrying guns, and the intimation that the king "done broke trade" with the last arrival was effected by his majesty sending off a canoe of oil to the ship, and the sending round of a verbal message by one of the king's men.

Since the year 1891 the kings of the Oil Rivers have been relieved of the duty of collecting comey, as a regular government of these rivers has been inaugurated by H.B.M. Government, comey being replaced by import duties.

NATIVE SYSTEM OF GOVERNMENT IN BENIN, AND RELIGION

Though there is a great similarity in the native form of government in these parts, it would be impossible to convey a true description of the manners and customs of the various places if I did not treat of each river and its people separately; I shall therefore commence by describing the people of Benin.

The Benin kingdom, so far as this account of it will go, was said to extend from the boundaries of the Mahin country (a district between the British Colony of Lagos and the Benin River) and the river Ramos; thus on the coast line embracing the rivers Benin, Escravos, and Forcados, also the hinterland, taking in Warri up to the Yoruba States.

For the purpose of the work I have set myself, I shall treat of that part of the kingdom that may be embraced by a line drawn from the mouth of the river Ramos up to the town of Warri, thence to Benin City, and brought down to the coast a little to the north of the Benin River. This tract of country is inhabited by four tribes, viz., the Jakri tribe, the dominant people on the coast line; the Sobo tribe, a very timid but most industrious people, great producers of palm oil, as well as being great agriculturists; an unfortunate people placed as they were between the extortions of the Jakris and the slave raiding of the Benin City king for his various sacrificial purposes; the third tribe are the Ijos, inhabiting the lower parts of the Escravos, Forcados, and Ramos rivers; this latter tribe are great canoe builders and agriculturists in a small way, produce a little palm oil, and by some people are accused of being cannibals; this latter accusation I don't think they deserve, in the full acceptation of the word, for thirty-three years ago I passed more than a week in one of their towns, when I was quite at their mercy, being accompanied by no armed men and carrying only a small revolver myself, which never came out of my pocket. Since when I have visited some of their towns on the Bassa Creek outside the boundary I have drawn for the purpose of this narrative, and never was I treated with the least disrespect.

The fourth tribe is the Benin people proper, whose territory is supposed to extend as far back as the boundaries of the Yoruba nation, starting from the right bank of the Benin River. In this territory is the once far-famed city of Benin, where lived the king, to whom the Jakri, the Sobo, and the Ijo tribes paid tribute.

These people have at all times since their first intercourse with Europeans, now some four hundred years, been renowned for their barbaric customs.

The earlier travellers who visited Benin City do not mention human sacrifices among these customs, but I have no doubt they took place; as these travellers were generally traders and wanted to return to Benin for trade purposes, they most likely thought the less said on the subject the best. I find, however, that in the last century more than one traveller mentions the sacrifice of human beings by the king of Benin, but do not lead one to imagine that it was carried to the frightful extent it has been carried on in later years.

I think myself that the custom of sacrificing human beings has been steadily increasing of late years, as the city of Benin became more and more a kind of holy city amongst the pagan tribes.

Their religion, like that of all the neighbouring pagans, admits of a Supreme Being, maker of all things, but as he is supposed to be always doing good, there is no necessity to sacrifice to him.

They, however, implicitly believe in a malignant spirit, to whom they sacrifice men and animals to satiate its thirst for blood and prevent it from doing them any harm.

Some of the pagan customs are of a sanitary character. Take, for instance, the yam custom. This custom is more or less observed all along the West Coast of Africa, and where it is unattended by any sacrificing of human or animal life, except the latter be to make a feast, it should be encouraged as a kind of harvest festival. When I say this was a sanitary law, I must explain that the new yams are a most dangerous article of food if eaten before the yam custom has been made, which takes place a certain time after the yams are found to be fit for taking out of the ground.

The new yams are often offered for sale to the Europeans at the earliest moment that they can be dug up, some weeks in many cases before the custom is made; the consequence is that many Europeans contract severe attacks of dysentery and fever about this time.

The well-to-do native never touches them before the proper time, but the poorer classes find it difficult to keep from eating them, as they are not only very sweet, but generally very cheap when they first come on the market.

The king of Benin was assisted in the government of his country and his tributaries by four principal officers; three of these were civil officers; these officers and the Ju-Ju men were the real governors of the country, the king being little more than a puppet in their hands.

It was these three officers who decided who should be appointed governor of the lower river, generally called New Benin.

Their choice as a rule fell upon the most influential chief of the district, their last choice being Nana, the son of the late chief Alumah, the most powerful and richest chief that had ever been known amongst the Jakri men. I shall have more to say about Nana when I am dealing with the Jakri tribe.

Amongst the principal annual customs held by the king of Old Benin, were the customs to his predecessors, generally called "making father" by the English-speaking native of the coast.

The coral custom was another great festival; besides these there were many occasional minor customs held to propitiate the spirit of the sun, the moon, the sky, and the earth. At most of these, if not all, human sacrifices were made.

Kings of Benin did not inherit by right of birth; the reigning king feeling that his time to leave this earth was approaching, would select his successor from amongst his sons, and calling his chief civil officer would confide to him the name of the one he had selected to follow him.

Upon the king's death this officer would take into his own charge the property of the late king, and receive the homage of all the expectant heirs; after enjoying the position of regent for some few days he would confide his secret to the chief war minister, and the chosen prince would be sent for and made to kneel, while they declared to him the will of his father. The prince thereupon would thank these two officers for their faithful services, and then he was immediately proclaimed king of Benin.

Now commences trouble for the non-successful claimants; the king's throne must be secure, so they and their sons must be suppressed. As it was not allowed to shed royal blood, they were quietly suffocated by having their noses, mouths and ears stuffed with cloth. To somewhat take the sting out of this cruel proceeding they were given a most pompous funeral.

Whilst on the subject of funerals I think I had better tell you something about the funeral customs of the Benineese.

When a king dies, it is said, his domestics solicit the honour of being buried with him, but this is only accorded to a few of his greatest favourites (I quite believe this to have been true, for I have seen myself slaves of defunct chiefs appealing to be allowed to join their late master); these slaves are let down into the grave alive, after the corpse has been placed therein. Graves of kings and chiefs in Western Africa being nice roomy apartments, generally about 12 feet by 8 by 14, but in Benin, I am told, the graves have a floor about 16 feet by 12, with sides tapering to an aperture that can be closed by a single flag-stone. On the morning following the interment, this flag-stone was removed, and the people down below asked if they had found the King. This question was put to them every successive morning, until no answer being returned it was concluded that the slaves had found their master. Meat was then roasted on the grave-stone and distributed amongst the people with a plentiful supply of drink, after which frightful orgies took place and great licence allowed to the populace—murders taking place and the bodies of the murdered people being brought as offerings to the departed, though at any other time murder was severely punished. Chiefs and women of distinction are also entitled to pompous funerals, with the usual accompaniment of massacred slaves. If a native of Benin City died in a distant part of the kingdom, the corpse used to be dried over a gentle fire and conveyed to this city for interment. Cases have been known where a body having been buried with all due honours and ceremonies, it has been afterwards taken up and the same ceremonies as before gone through a second time.

The usual funeral ceremonies for a person of distinction last about seven or eight days, and consist, besides the human sacrifices, of lamentations, dancing, singing and considerable drinking.

The near relatives mourn during several months—some with half their heads shaved, others completely shaven.

The law of inheritance for people of distinction differs from that of the kings in the fact that the eldest son inherits by right of primogeniture, and succeeds to all his father's property, wives and slaves. He generally allows his mother a separate establishment and maintenance and finds employment and maintenance for his father's other wives in the family residence. He is expected to act liberally with his younger brothers, but there is no law on this question. Before entering into full possession of his father's property he must petition the king to allow him to do so, accompanying the said petition with a present to the king of a slave, as also one to each of the three great officers of the king. This petition is invariably granted. A widow cannot marry again without the permission of her son, if she have a son; or if he be too young, the man who marries her must supply a female slave to wait upon him instead of his mother.

Theft was punished by fine only, if the stolen property was restored, but by flogging if the thief was unable to make restitution.

Murder was of rare occurrence. When detected it was punished with death by decapitation, and the body of the culprit was quartered and exposed to the beasts and birds of prey.

If the murderer be a man of some considerable position he was not executed, but escorted out of the country and never allowed to return.

In case of a murder committed in the heat of passion, the culprit could arrange matters by giving the dead person a suitable funeral, paying a heavy fine to the three chief officers of the king and supplying a slave to suffer in his place. In this case he was bound to kneel and keep his forehead touching the slave during his execution.

In all cases where an accusation was not clearly proved, the accused would have to undergo an ordeal to prove his guilt or innocence. To fully describe the whole of these would fill several hundred pages, and as most of them could be managed by the Ju-Ju men in such a way, that they could prove a man guilty or innocent according to the amount of present they had received from the accused's friends, I will pass on to other subjects.

Adultery was very severely punished in whatever class it took place; in the lower classes all the property of the guilty man passed at once to the injured husband, the woman being severely flogged and expelled from her husband's house.

Amongst the middle class this crime could be atoned for by the friends of the guilty woman making a money present to the injured husband; and the lady would be restored to her outraged lord's favour.

The upper classes revenged themselves by having the two culprits instantly put to death, except when the male culprit belonged to the upper classes; then the punishment was generally reduced to banishment from the kingdom of Benin for life.

Amongst these people one finds some peculiar customs concerning children. Amongst others, a child is supposed to be under great danger from evil spirits until it has passed its seventh day. On this day a small feast is provided by the parents; still it is thought well to propitiate the evil spirits by strewing a portion of the feast round the house where the child is.

Twin children, according to some accounts, were not looked upon with the same horror in Benin as they are in other parts of the Niger Delta; as a fact, they were looked upon with favour, except in one town of the kingdom, the name of which I have never been able to get, nor have I been able to locate the spot; but wherever it is, I am informed both mother and children were sacrificed to a demon, who resided in a wood in the neighbourhood of this town.

This law of killing twin children, like most Ju-Ju laws, could be got over if the father was himself not too deeply steeped in Ju-Juism, and was sufficiently wealthy to bribe the Ju-Ju priests. The law was always mercilessly carried out in the case of the poorer class of natives—the above refers solely to the part of Benin kingdom directly under the king of Old Benin, and does not hold good with regard to the Sobos, Jakris, or Ijos.

ORIGIN OF THE BENIN CITY PEOPLE

According to Clapperton the Benin people are descendants of the Yoruba tribes, the Yoruba tribes being descended from six brothers, all the sons of one mother. Their names were Ikelu, Egba, Ijebu, Ifé, Ibini (Benin), and Yoruba.

According to the late Sultan Bello (the Foulah chief of Sokoto at the time of Captain Clapperton's visit to that city), the Yoruba tribes are descended from the children of Canaan, who were of the tribe of Nimrod.

In my opinion there is room for much speculation on this statement of the Sultan Bello.

It is a very curious fact that the people of Benin City have been, from the earliest accounts we have of them, great workers in brass. Might not the ancestors of this people have brought the art of working in brass with them from the far distant land of Canaan? Moses, when speaking of the land of Canaan, says, "out of whose hills thou mayest dig brass" (Deut. viii. 9). Here we must understand copper to be meant; because brass is not dug out of the earth, but copper is, and found in abundance in that part of the world.

Yet another curious subject for reflection, from the first information that European travellers give us (circa 1485) in their descriptions of the city of Benin, mention has invariably made of towers, from the summits of which monster brass serpents were suspended. Upon the entry of the punitive expedition into Benin City in the month of February, 1897, Benin City still possessed one of these serpents in brass, not hanging from a tower, but laid upon the roof of one of the king's houses.

Might not these brazen serpents be a remnant of some tradition handed down from the time of Moses? for do we not read in the Scriptures, that the people of Israel had sinned; and God to punish them sent fiery serpents, which bit the people, and many died. Then Moses cried to God, and God told him to make a serpent of brass, and set it on a pole. (Numbers xxi. 9.)

While on the subject of serpents, I may mention that in the neighbourhood of Benin, there is a Ju-Ju ordeal pond or river, said to be infested with dangerous and poisonous snakes and alligators, through which a man accused of any crime passing unscathed proves his innocence.

There are some other customs connected with the position of the king of Benin, as the head of the Ju-Juism of his country, which seem to have some trace of a Biblical origin, but which I will not discuss here, but leave to the ethnologists to unravel, if they can.

That they were a superior people to the surrounding tribes is amply demonstrated by their being workers in brass and iron; displaying considerable art in some of their castings in brass, iron, copper and bronze, their carving in ivory, and their manufacture of cotton cloth—no other people in the Delta showing any such ability.

The Jakri tribe, who inhabit that part of the country lying between the Sobo country and the Ijo country, were the dominant tribe in the lower or New Benin country. Being themselves tributary to the Benin king, they dare not make the Sobo or Ijo men pay a direct tribute to them for the right to live, but they indirectly took a much larger tribute from them than ever they paid the king of Benin.

The Jakris were the brokers, and would not allow either of the above-named tribes to trade direct with the white men.

The principal towns of the Jakri men were:—Brohemie[3] (destroyed by the English in 1894): this town was generally called Nana's town of late years. Nana was Governor of the whole of the country lying between a line drawn from the Gwato Creek to Wari and the sea-coast; his governorship extending a little beyond the Benin River, and running down the coast to the Ramos River. This appointment he held from the king of Benin, and was officially recognised by the British Consul as the headman of the Jakri tribe, and for any official business in connection with the country over which he was Governor. Jeboo or Chief Peggy's town, situated on the waterway to Lagos; Jaquah town or Chief Ogrie's town. The above towns are all on the right bank of the river.

On the left bank of the river are found the following towns: Bateri, or Chief Numa's town, lying about half an hour's pull in a boat from Déli Creek. Chief Numa, was the son of the late Chief Chinomé, a rival in his day to Allumah, the father of Nana, the late Governor; Chinomé was the son of Queen Doto of Wari, who years ago was most anxious to see the white man at her town, and repeatedly advised the white men to use the Forcados for their principal trading station; but the old Chief Allumah was against any such exodus, and as he was a very big trader in palm-oil, he of course carried the day, and the white men stuck to their swamp at the mouth of the river Benin.

Close to Numa's town his brother Fragoni has established a small town. At some little distance from Bateri is Booboo, or the late Chief Bregbi's town. Galey, the eldest son of the late Chinomé, has a small town in the Déli Creek. This man, though the eldest son of the late Chief Chinomé, is not a chief, though his younger brother Numa is. Here is a knotty point in Jakri law of inheritance, which differs from the Benin City law on the subject.

Wari, the capital of Jakri, though almost if not actually as old a town as Benin City, has never had the bad reputation that the latter city has always had. I attribute this to the fact that the ladies of Warri have always been a power in the land.

Sapele is a place that has come very much into notice since the country has been under the jurisdiction of the Niger Coast Protectorate, and is without doubt one of the best stations on the Benin territory. I am glad to say that the Europeans have at last deserted to a great extent their factories at the mouth of the Benin River, and are now principally located at Sapele and Wari.

The Jakri tribe claim to be of the same race as the people of Benin City and kingdom. This I am inclined to dispute; I think they were a coast tribe like the Ijos. Tradition says that Wari was founded by people from Benin kingdom and for many years was tributary to the king of Benin, but in 1778 Wari was reported to be quite independent. They may have become almost the same race by intermarriage with the Benin people that went to Wari; but that they were originally the same race I say no.

The religion of the Jakri tribe and the native laws and system of ordeals were, as far as I have been able to ascertain, identical with those of the Benin kingdom; with the exception of the human sacrifices and their law of inheritance which does not admit the right of primo-geniture—following in this respect, the laws of the Bonny men and their neighbours. Twin children are usually killed by the Jakris, and the mother driven into the bush to die.

The Jakri tribe are, without doubt, one of the finest in the Niger Coast Protectorate; many of their present chiefs are very honest and intelligent men, also excellent traders. Their women are noted as being the finest and best looking for miles round.

The Jakri women have already made great strides towards their complete emancipation from the low state in which the women of neighbouring tribes still find themselves, many of them being very rich and great traders.

The Sobo tribe have been kept so much in the background by the Jakris that little is known about them. What little is known of them is to their credit.

We now come to the Ijo tribe, or at least, that portion of them that live within the Niger Coast Protectorate; these men are reported by some travellers to be cannibals, and a very turbulent people; this character has been given them by interested parties. Their looks are very much against them as they disfigure their faces by heavy cuts as tribal marks, and some pick up the flesh between their eyes making a kind of ridge, that gives them a savage expression. Though I have put the limit of these people at the river Ramos, they really extend along the coast as far as the western bank of the Akassa river. They have never had a chance and, with the exception of large timber for making canoes, their country does not produce much. Though I have seen considerable numbers of rubber-producing trees in their country, I never was able to induce them to work it. No doubt they asked the advice of their Ju-Ju as to taking my advice, and he followed the usual rule laid down by the priesthood of Ju-Ju-ism, no innovations.

Whilst I was in the Ijo country I carefully studied their Ju-Ju, as I had been told they were great believers in, and practisers of Ju-Ju-ism. I found little in their system differing from that practised in most of the rivers of the Delta.

In all these practices human agency plays a very large part, and this seems to be known even to the lower orders of the people; as an instance, I must here relate an experience I once had amongst the Ijos. I had arranged with a chief living on the Bassa Creek to lend me his fastest canoe and twenty-five of his people, to take me to the Brass river; the bargain was that his canoe should be ready at Cock-Crow Peak the following morning. I was ready at the water-side by the time appointed, but only about six of the smallest boys had put in an appearance; the old chief was there in a most furious rage, sending off messengers in all directions to find the canoe boys. After about two hours' work and the expenditure of much bad language on the part of the old chief, also some hard knocks administered to the canoe boys by the men who had been sent after them, as evidenced by the wales I saw on their backs, the canoe was at last manned, and I took my seat in it under a very good mat awning which nearly covered the canoe from end to end, and thanking my stars that now my troubles had come to an end I hoped at least for a time. I was, however, a very big bit too premature, for before the old chief would let the canoe start, he informed me he must make Ju-Ju for the safety of his canoe and the safe return of it and all his boys, to say nothing of my individual safety.

One of the first requirements of that particular Ju-Ju cost me further delay, for a bottle of gin had to be procured, and as the daily market in that town had not yet opened, and no public house had yet been established by any enterprising Ijo, it took some time to procure.

On the arrival of the article, however, my friend the old chief proceeded in a most impressive manner to repeat a short prayer, the principal portion I was able to understand and which was as follows: "I beg you, I beg you, don't capsize my canoe. If you do, don't drown any of my boys and don't do any harm to my friend the white man." This was addressed to the spirit of the water; having finished this little prayer, he next sprinkled a little gin about the bows of the canoe and in the river, afterwards taking a drink himself. He then produced a leaf with about an ounce of broken-up cooked yam mixed with a little palm oil, which he carefully fixed in the extreme foremost point of the canoe.

At last this ceremony was at an end and we started off, but alas! my troubles were only just beginning. We had been started about half an hour, and I had quietly dozed off into a pleasant sleep, when I was awakened by feeling the canoe rolling from side to side as if we were in rough water; just then the boys all stopped pulling, and on my remonstrance they informed me Ju-Ju "no will," id est, that the Ju-Ju had told them they must go back. I used gentle persuasion in the form of offers of extra pay at first, then I stormed and used strong language, or at least, what little Ijo strong language I knew, but all to no avail. I then began to inquire what Ju-Ju had spoken, and they pointed out a small bird that just then flew away into the bush; it looked to me something like a kingfisher. The head boy of the canoe then explained to me that this Ju-Ju bird having spoken, id est, chirped on the right-hand side of the canoe, and the goat's skull hanging up to the foremost awning stanchion having fallen the same way (this ornament I had not previously noticed), signified that we must turn back. So turn back we did, though I thought at the time the boys did not want to go the journey, owing to the almost continual state of quarrelling that had been going on for years between the Ijos and the Brassmen. I was not far wrong, for when we eventually did arrive at Brass, I had to hide these Ijo people in the hold of my ship, as the very sight of a Brassman made them shiver.

The following morning the same performance was gone through; we started, and at about the same point Ju-Ju spoke again; again we returned. My old friend the chief was very sorry he said, but he could not blame his boys for acting as they had done, Ju-Ju having told them to return. He would not listen when I told him I felt confident his boys had assisted the Ju-Ju by making the canoe roll about from side to side.

However, I thought the matter over to myself during that second day, and decided I would make sure one part of that Ju-Ju should not speak against me the next morning, and that was the goat's skull, so during that night after every Ijo was fast asleep, I visited that skull and carefully secured it to its post by a few turns of very fine fishing line in such a manner that no one could notice what I had done, if they did not specially examine it. I dare not fix it to the left, that being the favourable side, for fear of it being noticed, but I fixed it straight up and down, so that it could not demonstrate against my journey.

I retired to my sleeping quarters and slept the sleep of the just, and next morning started in the best of spirits, though continually haunted by the fear that my little stratagem might be discovered. We had got about the same distance from the town that we had on the two previous mornings when the canoe began to oscillate as usual, caused by a combined movement of all the boys in the canoe, I was perfectly convinced, for the creek we were in was as smooth as a mill pond. Many anxious glances were cast at the skull, and the canoe was made to roll more and more until the water slopped over into her, but the skull did not budge, and, strange to relate, the bird of ill omen did not show itself or chirp this morning, so the boys gave up making the canoe oscillate and commenced to paddle for all they were worth, and the following evening we arrived at my ship in Brass. We could have arrived much earlier, but the Ijos did not wish to meet with any Brassmen, so we waited until the shades of night came on, and thus passed unobserved several Brass canoes, arriving safely at my ship in time for dinner.

I carefully questioned the head boy of the Ijo boys all about this bird that had given me so much trouble. He explained to me that once having passed a certain point in the creek, the bird not having spoken and the skull not having demonstrated either, it was quite safe to continue on our journey, conveying to me the idea that this bird was a regular inhabitant of a certain portion of the bush, which was also their sacred bush wherein the Ju-Ju priests practised their most private devotions. The same species of bird showed itself several times both on the right of us and on the left of us as we passed through other creeks on our way to Brass, but the canoe boys took no notice of it.

In dealing with the Benin Kingdom I have allowed myself somewhat to encroach upon the Royal Niger Company's territory, which commences on the left bank of the river Forcados and takes in all the rivers down to the Nun (Akassa), and the sea-shore to leeward of this river as far as a point midway between the latter river and the mouth of the Brass river, thence a straight line is drawn to a place called Idu, on the Niger River, forming the eastern boundary between the Royal Niger Company's territory and the Niger Coast Protectorate. I have not defined the western boundary between the Royal Niger Company's territory and the other portion of the Niger Coast Protectorate otherwise than stating that it commences on the seashore at the eastern point of the Forcados.

Benin Kingdom, as a kingdom, may now be numbered with the past. For years the cruelties known to be enacted in the city of Benin have been such that it was only a question of ways and means that deterred the Protectorate officials from smashing up the place several years ago.

It is a very curious trait in the character of these savage kinglets of Western Africa how little they seem to have been impressed by the downfall of their brethren in neighbouring districts. Though they were well acquainted with all that was passing around them. Thus the fall of Ashantee in 1873 was well known to the King of Dahomey, yet he continued on his way and could not believe the French could ever upset him. Nana, the governor of the lower Benin or Jakri, could not see in the downfall of Ja Ja that the British Government were not to be trifled with by any petty king or governor of these rivers; though Nana was a most intelligent native, he had the temerity to show fight against the Protectorate officials, and of course he quickly found out his mistake, but alas! too late for his peace of mind and happiness; he is now a prisoner at large far away from his own country, stripped of all his riches and position. Here was an object lesson for Abu Bini, the King of Benin, right at his own door, every detail of which he must have heard of, or at least his Ju-Ju priests must have heard of the disaster that had happened to Nana, his satrap.

Nothing daunted Abu Bini and his Ju-Ju priests continued their evil practices; then came the frightful Benin massacre of Protectorate officials and European traders, besides a number of Jakris and Kruboys in the employment of the Protectorate.

The first shot that was fired that January morning, 1897, by the emissaries of King Abu Bini, sounded the downfall of the City of Benin and the end of all its atrocious and disgusting sacrificial rites, for scarcely three months after the punitive expedition camped in the King's Palace at old Benin.

The two expeditions that have had to be sent to Benin River within the last few years have been two unique specimens of what British sailors and soldiers have to cope with whilst protecting British subjects and their interests, no matter where situated.

I do not suppose that there are in England to-day one hundred people who know, and can therefore appreciate at its true value, the risk that each man in those two expeditions ran. In the attack on Nana's town the British sailors had to walk through a dirty, disgusting, slimy mangrove swamp, often sinking in the mud half way up their thighs, and this in the face of a sharp musketry fire coming from unseen enemies carefully hidden away, in some cases not five yards off, in dense bush, with occasional discharges of grape and canister. But nothing stopped them, and Nana's town was soon numbered with the things that had been.

It was the same to a great extent in the attack on Benin, only varied by the swamps not being quite so bad as at Nana's town, but the distance from the water side was much farther; in the former case one might say it was only a matter of minutes once in touch with the enemy; in the attack on Benin city it was a matter of several days marching through dense bush, where an enemy could get within five yards of you without being seen, and in some places nearer. Almost constantly under fire, besides a sun beating down on you so hot that where the soil was sandy you felt the heat almost unbearable through the soles of your boots, to say nothing of the minor troubles of being very short of drinking water, and at night not being able to sleep owing to the myriads of sand-flies and mosquitoes; getting now and again a perfume wafted under your nostrils, in comparison with which a London sewer would be eau de Cologne.

I was once under fire for twelve hours against European trained troops, so know something about a soldier's work, and for choice I would prefer a week's similar work in Europe to two hours' West African bush and swamp fighting, with its aids, fever and dysentery.

Before I quit Benin I want to mention one thing more about Ju-Ju. When the attack was made on Benin city, the first day's march had scarcely begun when two white men were killed and buried. After the column passed on, the natives came and dug the bodies up, cut their heads and hands off, and carried them up to Benin city to the Ju-Ju priests, who showed them to the king to prove to him that his Ju-Ju, managed by them, was greater than the white man's; in fact, the king, I am told, was being shown these heads and hands at the moment when the first rockets fell in Benin city. Those rockets proved to him the contrary, and he left the city quicker than he had ever done in his life before.

To point out to my readers how all the natives of the Delta believed in the power of the Benin Ju-Ju, I must tell you none of them believed the English had really captured the King until he was taken round and shown to them, the belief being that, on the approach of danger, he would be able to change himself into a bird and thus fly away and escape.

BRASS RIVER

Brass River is then the first river we have to deal with on the Niger Coast Protectorate, to the eastward of the Royal Niger Company's boundary.

The inhabitants of Brass call their country Nimbé and themselves Nimbé nungos, the latter word meaning people. Their principal towns were Obulambri and Basambri, divided only by a narrow creek dry at low water. In each of these towns resided a king, each having jurisdiction over separate districts of the Nimbé territory; thus the King of Obulambri was supposed to look after the district on the left hand of the River Brass, his jurisdiction extending as far as the River St. Barbara. The King of Basambri's district extended from the right bank of the Brass River, westward as far as the Middleton outfalls; included in this district was the Nun mouth of the River Niger. These two kinglets had a very prosperous time during the closing days of the slave trade, as most of the contraband was carried on through the Brass and the Nun River both by Bonnymen and New Calabar men after they had signed treaties with Her Majesty's Government to discontinue the slave trade in their dominions. When eventually the trade in slaves was finally put down their prosperity was not at an end, for they went largely into the palm oil trade, and did a most prosperous trade along the banks of the Niger as far as Onitsa.

Though these two kings always objected to the white men opening up the Niger, and did their utmost to retard the first expeditions, they were not slow in demanding comey from the early traders who established factories in the Nun mouth of the Niger; this part of the Niger is also called the Akassa.

These people are a very mixed race, and to describe them as any particular tribe would be an error. I believe the original inhabitants of the mouths of these rivers were the Ijos, and that the towns of Obulambri and Bassambri were founded by some of the more adventurous spirits amongst the men from the neighbourhood of Sabogrega, a town on the Niger; being afterwards joined by some similar adventurers from Bonny River. The three people are closely connected by family ties at this day.

As a rule these people have always had the character of being a well behaved set of men; it is a notable fact in their favour that they were the only people that, once having signed the treaty with Her Majesty's Government to put down slavery, honestly stuck to the terms of the treaty; unlike their neighbours, they did so, though they were the only people who did not receive any indemnity. They, however, have occasionally lost their heads and gone to excesses unworthy of a people with such a good reputation as they have generally enjoyed.

Their last escapade was the attack on the factory of the Royal Niger Company at Akassa some few years ago, and for which they were duly punished; their dual mud and thatch capital was blown down, and one small town called Fishtown destroyed.

Impartial observers must have pitied these poor people driven to despair by being cut off from their trading markets by the fiscal arrangements of the Royal Niger Company. The latter I don't blame very much, they are traders; but the line drawn from Idu to a point midway between the Brass River and the Nun entrance to the Niger River, as being the boundary line for fiscal purposes between the Royal Niger Company and the Niger Coast Protectorate, was drawn by some one at Downing Street who evidently looked upon this part of the world as a cheesemonger would a cheese.

In 1830 it was at Abo on the Niger where Lander the traveller met with the Brassmen, who took him down to Obulambri, but no ship being in Brass River, they took him and his people over to Akassa, at the Nun mouth of the Niger, to an English ship lying there. History says he was anything but well received by the captain of this vessel, and that the Brassmen did not treat him as well as they might; however, they did not eat him, as they no doubt would have done could they have looked into the future. Whatever their treatment of Lander was, it could not have been very bad, as they received some reward for what assistance they had given him some time after.

It was amongst these people that I was enabled to study more closely the inner working of the domestic slavery of this part of Western Africa, and where it was carried on with less hardship to the slaves themselves than any place else in the Delta, until the Niger Company's boundary line threw most of the labouring population on the rates, at least they would have gone on the rates if there had been any to go on, but unfortunately the municipal arrangements of these African kingdomlets had not arrived at such a pitch of civilisation; the consequence was many died from starvation, others hired themselves out as labourers, but the demand for their services was limited, as they compared badly with the fine, athletic Krumen, who monopolise all the labour in these parts. Then came the punitive expedition for the attack on Akassa that wiped off a few more of the population, so that to-day the Brassmen may be described as a vanishing people.

The various grades of the people in Brass were the kings, next came the chiefs and their sons who had by their own industry, and assisted in their first endeavours by their parents, worked themselves into a position of wealth, then came the Winna-boes, a grade mostly supplied by the favourite slave of a chief, who had been his constant attendant for years, commencing his career by carrying his master's pocket-handkerchief and snuff-box, pockets not having yet been introduced into the native costume; after some years of this duty he would be promoted to going down to the European traders to superintend the delivery of a canoe of oil, seeing to its being tried, gauged, &c. This first duty, if properly performed, would lead to his being often sent on the same errand. This duty required a certain amount of savez, as the natives call intelligence, for he had to so look after his master's interests that the pull-away boys that were with him in the canoe did not secrete any few gallons of oil that there might be left over after filling up all the casks he had been sent to deliver; nor must he allow the white trader to under-gauge his master's casks by carelessness or otherwise. If he was able to do the latter part of his errand in such a diplomatic manner that he did not raise the bile of the trader, that day marked the commencement of his upward career, if he was possessed of the bump of saving. All having gone off to the satisfaction of both parties, the trader would make this boy some small present according to the number of puncheons of oil he had brought down, seldom less than a piece of cloth worth about 2s. 6d., and, in the case of canoes containing ten to fifteen puncheons, the trader would often dash him two pieces of cloth and a bunch or two of beads. This present he would, on his return to his master's house, hand over to his mother (id est, the woman who had taken care of him from the time when he was first bought by his Brass master). She would carefully hoard this and all subsequent bits of miscellaneous property until he had in his foster-mother's hands sufficient goods to buy an angbar of oil—a measure containing thirty gallons. Then he would approach his master (always called "father" by his slaves) and beg permission to send his few goods to the Niger markets the next time his master had a canoe starting—which permission was always accorded. He had next to arrange terms with the head man or trader of his master's canoe as to what commission he had to get for trading off the goods in the far market. In this discussion, which may occupy many days before it is finally arranged, the foster-mother figures largely ; and it depends a great deal upon her standing in the household of the chief as to the amount of commission the trade boy will demand for his services. If the foster-mother should happen to be a favourite wife of the chief, well, then things are settled very easily, the trade boy most likely saying he was quite willing to leff-em to be settled any way she liked; if, on the contrary, it was one of the poorer women of the chief's house, Mr. Trade-boy would demand at least the quarter of the trade to commence with, and end up by accepting about an eighth. As the winnabo could easily double his property twice a year—and he was always adding to his store in his foster-mother's hands from presents received each time he went down to the white trader with his father's oil—it did not take many years for him to become a man of means, and own canoes and slaves himself. Many times have I known cases where the winnabo has repeatedly paid up the debts of his master to the white man.

According to the law of the country, the master has the right to sell the very man who is paying his debts off for him; but I must say I never heard a case of such rank ingratitude, though cases have occurred where the master has got into such low water and such desperate difficulties that his creditors under country law have seized everything he was possessed of, including any wealthy winnaboes he might have.

Some writers have said this class could purchase their freedom; with this I don't agree. The only chance a winnabo had of getting his freedom was, supposing his master died and left no sons behind him old enough or capable enough to take the place of their father, then the winnabo might be elected to take the place of his defunct master: he would then become ipso facto a chief, and be reckoned a free man. If he was a man of strong character, he would hold until his death all the property of the house; but if one of the sons of his late master should grow up an intelligent man, and amass sufficient riches to gather round him some of the other chief men in the town, then the question was liable to be re-opened, and the winnabo might have to part out some of the property and the people he had received upon his appointment to the headship of the house, together with a certain sum in goods or oil, which the elders of the town would decide should represent the increment on the portion handed over. I have never known of a case where the whole of the property and people have been taken away from a winnabo in Brass; but I have known it occur in other rivers, but only for absolute misuse, misrule, and misconduct of the party.

Egbo-boes are the niggers or absolute lower rank of slaves, who are employed as pull-away boys in the oil canoes and gigs of the chiefs, and do all the menial work or hard labour of the towns that is not done by the lower ranks of the women slaves.

The lot of these egbo-boes is a very hard one at times, especially when their masters have no use for them in their oil canoes. At the best of times their masters don't provide them with more food then is about sufficient for one good square meal a day; but, when trade is dull and they have no use for them in any way, their lot is deplorable indeed. This class has suffered terribly during the last ten years owing to the complete stoppage of the Brassmen's trade in the Niger markets.

This class had few chances of rising in the social scale, but it was from this class that sprang some of the best trade boys who took their masters' goods away up to Abo and occasionally as far as Onitsa, on the Niger.

Cases have occurred of boys from this class rising to as good a position as the more favoured winnaboes; but for this they have had to thank some white trader, who has taken a fancy to here and there one of them, and getting his master to lend him to him as a cabin boy—a position generally sought after by the sons of chiefs, so as to learn "white man's mouth," otherwise English.

The succession laws are similar to those of the other Coast tribes one meets with in the Delta, but to understand them it requires some little explanation. A tribe is composed of a king and a number of chiefs. Each chief has a number of petty chiefs under him. Perhaps a better definition for the latter would be, a number of men who own a few slaves and a few canoes of their own, and do an independent trade with the white men, but who pay to their chiefs a tribute of from 20 to 25 per cent. on their trade with the white man. In many cases the white man stops this tribute from the petty chiefs and holds it on behalf of the chief. This collection of petty chiefs with their chief forms what in Coast parlance is denominated a House.

The House may own a portion of the principal town, say Obulambri, and also a portion in any of the small towns in the neighbouring creeks, and it may own here and there isolated pieces of ground where some petty chief has squatted and made a clearance either as a farm or to place a few of his family there as fishermen ; in the same way the chief of the house may have squatted on various plots of ground in any part of the district admitted by the neighbouring tribes to belong to his tribe. All these parcels and portions of land belong in common to the House—that is, supposing a petty chief having a farm in any part of the district was to die leaving no male heirs and no one fit to take his place, the chief as head of the house would take possession, but would most likely leave the slaves of the dead man undisturbed in charge of the farm they had been working on, only expecting them to deliver him a portion of the produce equivalent to what they had been in the habit of delivering to their late master, who was a petty chief of the house.

The head of the house would have the right of disposal of all the dead man's wives, generally speaking the younger ones would be taken by the chief, the others he would dispose of amongst his petty chiefs; if, as generally happens, there were a few aged ones amongst them for whom there was no demand he would take them into his own establishment and see they were provided for.

As a matter of fact, all the people belonging to a defunct petty chief become the property of the head of the house under any circumstances; but if the defunct had left any man capable of succeeding him, the head chief would allow this man to succeed without interfering with him in any way, provided he never had had the misfortune to raise the chief's bile; in the latter case, if the chief was a very powerful chief, whose actions no one dare question, the chances are that he would either be suppressed or have to go to Long Ju-Ju to prosecute his claim, the expenses of which journey would most likely eat up the whole of the inheritance, or at least cripple him for life as far as his commercial transactions were concerned. It is of course to the interest of the head of a house to surround himself with as many petty chiefs as he possibly can, as their success in trade, and in amassing riches whether in slaves or goods, always benefits him; even in those rivers where no heavy "top-side" is paid to the head of the house by the white traders, the small men or petty chiefs are called upon from time to time to help to uphold the dignity of the head chief, either by voluntary offerings or forced payments. Public opinion has a good deal to say on the subject of succession; and though a chief may be so powerful during his lifetime that he may ride roughshod over custom or public opinion, after his death his successor may find so many cases of malversation brought against the late chief by people who would not have dared to open their mouths during the late chief's lifetime, that by the time they are all settled he finds that a chief's life is not a happy one at all times. Claims of various kinds may be brought up during the lifetime of a chief, and three or four of his successors may have the same claim brought against them, each party may think he has settled the matter for ever; but unless he has taken worst, the descendants of the original claimants will keep attacking each successor until they strike one who is not strong enough to hold his own against them, and they succeed in getting their claim settled. This settlement does not interfere with the losing side turning round and becoming the claimants in their turn. Some of these family disputes are very curious; take for instance a case of a claim for five female slaves that may have been wrongfully taken possession of by some former chief of a house, this case perhaps is kept warm, waiting the right moment to put it forward, for thirty years, the claim then becomes not only for the original five women, but for their children's children and so on.

RELIGION

The Brass natives to-day are divided into two camps as far as religion is concerned: the missionary would no doubt say the greater number of them are Christians, the ordinary observer would make exactly the opposite observation, and judging from what we know has taken place in their towns within the last few years, I am afraid the latter would be right.

The Church Missionary Society started a mission here in 1868; it is still working under another name, and is under the superintendence of the Rev. Archdeacon Crowther, a son of the late Bishop Crowther.

Their success, as far as numbers of attendants at church, has been very considerable; and I have known cases amongst the women who were thoroughly imbued with the Christian religion, and acted up to its teaching as conscientiously as their white sisters; these however are few.

With regard to the men converts I have not met with one of whom I could speak in the same terms as I have done of the women.

Whilst fully recognising the efforts that the missionaries have put forth in this part of the world, I regret I can't bear witness to any great good they have done.

This mission has been worked on the usual lines that English missions have been worked in the past, so I must attribute any want of success here as much to the system as anything.

One of the great obstacles to the spread of Christianity in these parts is in my opinion the custom of polygamy, together with which are mixed up certain domestic customs that are much more difficult to eradicate than the teachings of Ju-Ju, and require a special mission for them alone.

Almost equal to the above as an obstacle in the way of Christianity is what is called domestic slavery; Europeans who have visited Western Africa speak of this as a kind of slavery wherein there is no hardship for the slave; they point to cases where slaves have risen to be kings and chiefs, and many others who have been able to arrive at the position of petty chief in some big man's house. I grant all this, but all these people forget to mention that until these slaves are chiefs they are not safe; that any grade less than that of a chief that a slave may arrive to does not secure him from being sold if his master so wished.

Further, domestic slavery gives a chief power of life and death over his slave; and how often have I known cases where promising young slaves have done something to vex their chief their heads have paid the penalty, though these young men had already amassed some wealth, having also several wives and children.

People who condone domestic slavery, and I have heard many kindly-hearted people do so, forget that however mild the slavery of the domestic slave is on the coast, even under the mildest native it is still slavery; further, these slaves are not made out of wood, they are flesh and blood, they in their own country have had fathers and mothers. During my lengthened stay on the coast of Africa I never questioned a slave about his or her own country that I did not find they much preferred their own country far away in the interior to their new home. Some have told me that they had been travelling upwards of two months and had been handed from one slave dealer to another, in some cases changing their owner three or four times before reaching the coast. On questioning them how they became slaves, I have only been told by one that her father sold her because he was in debt; several times I have been told that their elder brothers have sold them, but these cases would not represent one per cent. of the slaves I have questioned; the almost general reply I have received has been that they had been stolen when they had gone to fetch water from the river or the spring, as the case might be, or while they have been straying a little in the bush paths between their village and another. Sometimes they would describe how the slave-catchers had enticed them into the bush by showing them some gaudy piece of cloth or offered them a few beads or negro bells, others had been captured in some raid by one town or village on another.

Therefore domestic slavery in its effect on the interior tribes is doing very near the same amount of harm now that it did in days gone by. It keeps up a constant fear of strangers, and causes terrible feuds between the villages in the interior.

What is the use of all the missionaries' teaching to the young girl slaves so long as they are only chattels, and are forced to do the bidding of their masters or mistresses, however degrading or filthy that bidding may be?

The Ju-Juism of Brass is a sturdy plant, that takes a great deal of uprooting. A few years ago a casual observer would have been inclined to say the missionaries are making giant strides amongst these people. I remember, as evidence of how keenly these people seemed to take to Christianity up to a certain point, a little anecdote that the late Bishop Crowther once told me about the Brass men. I think it must have been a very few years before his death. I saw the worthy bishop staggering along my wharf with an old rice bag full of some heavy articles. On arriving on my verandah he threw the bag down, and after passing the usual compliments, he said, "You can't guess what I have got in that bag." I replied I was only good at guessing the contents of a bag when the bag was opened; but judging from the weight and the peculiar lumpy look of the outside of the bag, I should be inclined to guess yams. "Had he brought me a present of yams?" I continued. "No," he replied; "the contents of that bag are my new church seats in the town of Nimbé; the church was only finished during the week, and I decided to hold a service in it on Sunday last; and, do you believe me, those logs of wood are a sample of all we had for seats for most part of the congregation! I have therefore brought them down to show you white gentlemen our poverty, and to beg some planks to make forms for the church." I promised to assist him, and he left, carefully walking off with his bag of fire-wood, for that was all it was, cut in lengths of about fifteen inches, and about four inches in diameter. Here ends my anecdote, so far as the bishop was concerned, for he never came back to claim the fulfilment of my promise; but later on one of my clerks reported to me that there had been a great run on inch planks during the week, and that the purchasers were mostly women, and the poorest natives in the place. This fact, coupled with the fact that the bishop never came back for the planks he had begged of me, caused me to make some inquiries, and I found that the church had been plentifully supplied with benches by the poorer portion of the congregation.

Yet how many of these earnest people could one guarantee to have completely cast out all their belief in Ju-Juism? If I were put upon my oath to answer truthfully according to my own individual belief, I am afraid my answer would be not one.

What an awful injustice the missionary preaches in the estimation of the average native woman, when he advises the native of West Africa to put away all his wives but one. Supposing, for instance, it is the case of a big chief with a moderate number of wives, say only twenty or thirty, he may have had children by all of them, or he may have had children by a half dozen of them,—what is to become of those wives he discards? are they to be condemned to single blessedness for the remainder of their days? Native custom or etiquette would not allow these women to marry the other men in the chief's house; they can't marry into other houses, because they would find the same condition of things there as in their own husband's house, always supposing Christianity was becoming general. These difficulties in the way of the missionary are the Ju-Ju priests' levers, which they know well how to use against Christianity, and which accounts for the frequent slide back to Ju-Juism, and in some cases cannibalism of otherwise apparently semi-civilized Africans.

The Pagan portion of the inhabitants of the Brass district have still their old belief in the Ju-Ju priests and animal worship.

The python is the Brass natives' titular guardian angel. So great was the veneration of this Ju-Ju snake in former times, that the native kings would sign no treaties with her Britannic Majesty's Government that did not include a clause subjecting any European to a heavy fine for killing or molesting in any way this hideous reptile. When one appeared in any European's compound, the latter was bound to send for the nearest Ju-Ju priest to come and remove it, for which service the priest expected a dash, id est, a present; if he did not get it, the chances were the priest would take good care to see that that European found more pythons visited him than his neighbours; and as a rule these snakes were not found until they had made a good meal of one of the white man's goats or turkeys, it came cheaper in the long run to make the usual present.

It is now some twenty years ago that the then agent of Messrs. Hatton and Cookson in Brass River found a large python in his house, and killed it. This coming to the ears of the natives and the Ju-Ju priests, caused no little excitement; the latter saw their opportunity, worked up the people to a state of frenzy, and eventually led them in an attack on the factory of Messrs. Hatton and Cookson, seized the agent and dragged him out of his house on to the beach, tied him up by his thumbs, each Ju-Ju priest present spat in his mouth, afterwards they stripped him naked and otherwise ill treated him, besides breaking into his store and robbing him of twenty pounds worth of goods. The British Consul was appealed to for redress, and upon his next visit to the river inquired into the case, but, mirabile dictu, decided that he was unable to afford the agent any redress, as he had brought the punishment on himself. I don't mention the name of this Consul, as it would be a pity to hand down to posterity the fact that England was ever represented by such an idiot.

Besides the python the Brass men had several other secondary Ju-Jus; amongst others may be mentioned the grey and white kingfisher, also another small bird like a water-wagtail, besides which, in common with their neighbours, they believed in a spirit of the water who was supposed to dwell down by the Bar, and to which they occasionally made offerings in the shape of a young slave-girl of the lightest complexion they could buy.

The burial customs of this people differed little from others in the Niger Delta, but as I was present at the burial of two of their kings—viz. King Keya and King Arishima, at which I saw identically the same ceremonial take place, I will describe what I saw as far as my memory will serve me, for the last of these took place about thirty years ago.

The grave in this instance was not dug in a house, but on a piece of open ground close to the king's house, but was afterwards roofed over and joined on to the king's houses. The size of the grave was about fourteen by twelve feet, and about eight feet deep. At the end where the defunct's head would be, was a small table with a cloth laid over it, upon this were several bottles of different liquors, a large piece of cooked salt beef and sundry other cooked meats, ship's biscuits, &c. The ceiling of this chamber was supported by stout beams being laid across the opening, upon which would be placed planks after the body had been lowered into position, then the whole would be covered over with a part of the clay that had been taken out of the hole, the rest of the clay being afterwards used to form the walls of the house, that was eventually constructed over the grave; a small round hole about three inches in diameter being made in the ceiling of the grave, apparently about over the place where the head of the corpse would lay. Down this would be poured palm wine and spirits on the aniversaries of the king's death, by his successor and by the Ju-Ju priests. This part of the ceremony would be called "making his father," if it was a son who succeeded; if it was not a son, he would describe it as "making his big father"; though he was perhaps no blood relation at all.

Previous to the burial the body of the king lay in state for two days in a small hut scarcely five feet high, with very open trellis work sides. I believe they would have kept the body unburied longer if they could have done so, but at the end of the second day his Highness commenced to be very objectionable. The king's body was dressed for this ceremony in his most expensive robes, having round the neck several necklaces of valuable coral, to which his chiefs would add a string more or less valuable according to their means, as they arrived for the final ceremony. The Europeans were expected to contribute something towards the funeral expenses, which contribution generally consisted of a cask of beef, a barrel of rum, a hundredweight of ship's biscuits, and from twenty to thirty pieces of cloth. Even in this there was a certain amount of rivalry shown by the Europeans, to their loss and the natives' gain. One knowing trader amongst them on this occasion had just received a consignment of imitation coral, an article at that time quite unknown in the river, either to European trader or to natives; so he decided to place one of these strings of imitation coral round the king's neck himself, and thus create a great sensation, for had it been real coral its value would have been one hundred pounds. He had, however, not counted on the king's very objectionable state, and when he proceeded to place his offering round the king's neck, he nearly came to grief, and did not seem quite himself until he had had a good stiff glass of brandy and water. The news spread like wildfire of this man's munificence, and soon the principal chiefs waited upon him to thank him for his present to their dead king; the other Europeans were green with jealousy, though each had in his turn tried to outdo his neighbour; unfortunately, there was a Scotchman there "takin' notes," and faith he guessed a ruse, but he was a good fellow and friend of the donor, and kept the secret for some years, and did not tell the tale until it could do his friend no harm.

The cannons had been going off at intervals for the last two days. Towards ten o'clock of the second night after death the king was placed in a very open-work wicker casket, and carried shoulder high round the town, and then finally deposited in his grave. During this time the cannons were being continually fired off, and individuals were assisting in the din by firing off the ordinary trade gun. I and another European concealed ourselves near the grave, and carefully watched all night to see if they sacrificed any slaves on the king's grave, or put any poor creatures down into the grave to die a lingering death; but we saw nothing of this done, though we had been informed that no king or chief of Brass was ever buried without some of his slaves being sent with him into the next world; as our informant explained, how would they know he had been a big man in this life if he did not go accompanied by some of his niggers into the next?

The firing of cannon is kept up at intervals for an indefinite number of days after the final interment; but there is no hard and fast rule as to its duration as far as I have been able to ascertain, and I think myself it is ruled by the greater or less liberality of the successors, who are the ones who have to pay for the gunpowder.

Amongst other customs that are common to all these rivers and this river is the killing of twin children; but since the mission has been established here the missionaries have done their utmost to wean the people from this remnant of savagery.

A curious custom that I have heard of in most of these rivers is the throwing into the bush, to be devoured by the wild beasts, any children that may be born with their front teeth cut. I found this custom in Brass, but with an exception, id est, I knew a pilot in Twon Town who had had the misfortune to be born with his upper front teeth through; whether it was because it was only the upper teeth that were through, or whether it was that the law is not so strictly carried out in the case of a male, I was never able to make sure of; however, he had been allowed to live, but it appears in his case some part of the law had to be carried out at his death, viz. he was not allowed to be buried, but was thrown into the bush, to fall a prey to the wild beasts, and any property he might die possessed of could not be inherited by any one, but must be dissipated or thrown into the bush to rot. I believe the Venerable Archdeacon Crowther has been instrumental in saving several of these kind of children in Bonny.

The women of Brass are, like their sisters in Benin river, moving on towards women's rights; for though they have been for many generations the hewers of wood and drawers of water, and made to do most of the hard work of the country, they had commenced some years ago to enjoy more freedom than their sisters in the leeward rivers. They still do most of the fishing, and the fishing girls of Twon Town used to present a pretty sight as some fifteen or twenty of their tiny canoes used to sweep past the European factories, each canoe propelled by two or three graceful, laughing, chattering girls; with them would generally be seen a canoe or two paddled by some dames of a maturer age. Though passée as far as their looks were concerned, they could still ply their paddle as well as the best amongst the younger ones, as they forced their frail canoes through water to some favourite quiet blind creek where the currentless water allowed them to use their preparation[4] for stupefying the fish, and in little over three hours you might see them come paddling back, each tiny canoe with from fifty to a hundred small grey mullet, sometimes with more and occasionally with a few small river soles.

The Brass man, like his neighbours, had his public Ju-Ju house as well as his private little Ju-Ju chamber, the latter was to be found in any Brass man's establishment which boasted of more than one room; those who could not afford a separate chamber used to devote a corner of their own room, where might be seen sundry odds and ends bespattered with some yellow clay, and occasionally a white fowl hung by the leg to remain there and die of starvation and drop gradually to pieces as it decomposed.

The public Ju-Ju house at Obulambri was not a very pretentious affair; it consisted of a native hut of wattle and daub, the walls not being carried more than half way up to the eaves, roofed with palm mats; in the centre was an iron staff about five feet high, surrounded by eight bent spear heads; this was called a tokoi, at the foot of it was a hole about three inches in diameter, down which the Ju-Ju priests would pour libations of tombo or palm wine, as a sacrifice to the Ju-Ju. I was informed that this Ju-Ju house was built over the grave of the original founder of Obulambri town. Behind the tokoi, on a kind of altar raised about eighteen inches from the ground, were displayed about a dozen human skulls; at the time I visited it the Ju-Ju man explained to me that the greater part of these had belonged to New Calabar prisoners taken in their last war with those people; besides the skulls were sundry odds and ends of native pottery, as also a few bowls and jugs of European manufacture. What part this pottery played in their devotions I could never get a Ju-Ju man to explain, some of them appeared to have held human blood. Stacked up in one corner were a few human bones, principally thigh and shin bones.

The Brassmen do not often sacrifice human beings to their Ju-Jus, except in time of war, when all prisoners without exception were sacrificed.