CHAPTER XII.

MANATON

THE position of Manaton is one of remarkable beauty, between Lustleigh Cleave and the ridge on which stands Bowerman's Nose, and which swells up to Hound Tor.

The church is dedicated to S. Winefred, the Welsh martyr maid, and has its fine screen carefully restored. It formerly possessed a singular feature, which the "restoring" architect destroyed, because singular. This was a small window in the east wall opening from the outside, under the altar. Perhaps there were relics of S. Winefred kept beneath the altar, and through this fenestrella confessionis the devotees could touch them. But, indeed, the destroyer has been at Manaton and effaced more than this window. On the tor that commands the village were formerly many prehistoric monuments. The farm Langstone by its name proclaims that on it was a menhir. In the churchyard was a fine granite cross. A former rector, the Rev. C. Carwithen, wantonly destroyed it in the night. The people had been wont at a funeral to carry the corpse the way of the sun thrice round the cross before interment. He preached against the custom ineffectually, so he secretly smashed the cross. There are two logan rocks within easy reach—the Whooping Stone on Easdon, and the Nutcracker in Lustleigh Cleave.

This cleave is very picturesque. "Cleave" properly is a local softening of the word "cliff," and applies to the rocks, but in common use it has come incorrectly to be applied to the valley below the crags. Through the stone-strewn trough of the vale the sparkling Bovey finds its way with some difficulty, diving under the boulders at Horsham Steps, and running unseen for some considerable distance, only proclaiming its presence by its murmurs and whispers.

That there was some fighting done across this valley is probable, because there are camps on both sides.

In honourable contrast with Mr. Carwithen stands Mr. Jones, the curate of North Bovey, who fished the old village cross out of the brook, where it had lain since the iconoclastic period of the Civil Wars, and re-erected it in 1829.

North Bovey church, pleasantly situated, possesses a screen much mutilated, but capable of restoration. Far superior to it in preservation is that of Lustleigh, which is of the same character as that of Bridford, perhaps post-Reformation, and contains a series of figures in the lower compartments representing clergy in their caps and surplices and "liripipets," and not saints. There is some old glass in the church, in one window a representation of S. Margaret. There are monumental effigies in the church of the Prouze family. One of these is of Sir William Prouze, to whom the manor of Lustleigh belonged. By his will he directed that he should be buried with his ancestors at Lustleigh; but he died at a distance, and was interred at Holbeton. Some time after, the wishes of her father having come to the knowledge of Lady Alice, the wife of Sir Roger Mules, Baron of Cadbury, and finding that they had been disregarded, the dutiful daughter petitioned Grandisson, Bishop of Exeter in 1329, that the remains might be removed from Holbeton to Lustleigh, and the prayer was granted.

Forming the sill of the south door is a long granite stone with a Romano-British inscription, the reading of which has not been satisfactorily made out.

In the chancel may be noticed the stone brackets, perforated for the cords employed for the suspension of the Lenten veil.

A story associated with Lustleigh church has its parallels elsewhere. After it had been built the devil threatened to destroy it, stained glass and all, unless he were given a sacrifice. Now it happened that a bumpkin was present in the churchyard with a pack of cards in his pocket, and the Evil One immediately demanded him as his due; but the man, with great presence of mind, pounced on a cat that was stalking by and dashed out its brains against the wall of the porch. This satisfied the powers of darkness, and the consecration of the church followed. The story is a clumsy late cooking up of the old belief that before a building could be occupied a life must be sacrificed to the telluric deities. A horse, a dog, a sow—in this case a cat was offered up. Echoes of the same are found everywhere.[1] Most Devonshire churchyards were formerly supposed to be haunted by some animal or other, which had been buried under the corner-stone. When S. Columba took possession of lona the question arose as to who was to die and be buried so as to secure the place for ever to the community. One of his monks, Oran by name, offered himself, and he was buried alive under the foundations of the new abbey.

The rectory house possesses its ancient hall open to the roof. In the hedge between the church and station is the "Bishop's Stone," a large block, bearing the arms of Bishop Stapeldon (1307-26), who was murdered in the riots occasioned by Edward II. favouring the Despensers. He was fallen on by the London mob in Cheapside, stripped, and beheaded by them.

Strewn about Lustleigh are numerous masses of granite, rounded, and like loaves of bread. This is due to the weathering of the granite, which is soft, but some, if not most, appear to have been carried to where they lie by water.

The stream Becka forms a fall into the valley of the Bovey, through woods, but except in very rainy

Hound Tor

The eastern flank of the moor is infinitely richer in vegetation than the western. The whole of Dartmoor stands up as a wall against the prevalent north-west and south-west winds that distort the trees on the west side. Moreover, owing to the shelter thus furnished, and to the disintegration of the granite trending in this direction so as to form deep beds of gravel, the valleys and hillsides are clothed with rich vegetation. Pines flourish.

Hound Tor is a noble mass of rocks. It derives its name from the shape assumed by the blocks on the summit, that have been weathered into forms resembling the heads of dogs peering over the natural battlements, and listening to hear the merry call of the horn. Below it, on the Manaton side, nestles Hound Tor Farm, picturesquely enfolded in a sycamore grove.

The sycamore, by the way, is peculiarly the tree for Dartmoor and other exposed situations. The beech cowers and turns from the blast, and it divides so soon as its taproot touches rock; but the sycamore stands up, indifferent to wind and rain, to which it opposes the broad green leaves that it turns against the blast, and so shelters itself as with scale armour.

On Hound Tor is a circle of stones containing a kistvaen.

The road that leads to Widdecombe and Ashburton ascends to Hound Tor; but there is another road to Ashburton by Hey Tor that branches off to the left before Hound Tor Farm is reached, and scrambles up to Trendlebere Down, passing an almost destroyed stone row starting from a cairn beside the highway. The road runs at a great elevation (1,080 feet) for some miles. There is a pleasant and homely inn at Hey Tor Vale, where the traveller may rest and gather strength to visit Holwell Tor and Hey Tor Rocks. Holwell Tor was at one time surrounded by a stone rampart, but quarrymen have sadly injured it, and it is not now easy to decide whether the inclosure was merely a pound, like Grimspound, or a stone camp, like Whit Tor.

Hey Tor Rocks form two fine masses, and are unlike most of the moorland tors, in that the granite is very consistent, and is not broken into the usual layers of soft beds alternating with hard layers. The view of the valley below Hey Tor and Grea Tor on one side, and the ridge of Bone Hill on the other, is fine.

The road, commanding to the east a vast stretch of the rich lowlands of Devon, passes Saddle Tor and reaches Rippon Tor, where is a good logan stone. Here are several cairns much mutilated by

the road-makers. On the further side of the road, by Pill Tor, are remains of an extensive prehistoric settlement. Many huts and inclosures remain. The place bears the name of Foale's Arrishes, from a man of that appellation who spent his energies in converting the prehistoric inclosures into fields for his own use, to the destruction of much that was

Hey Tor Rocks

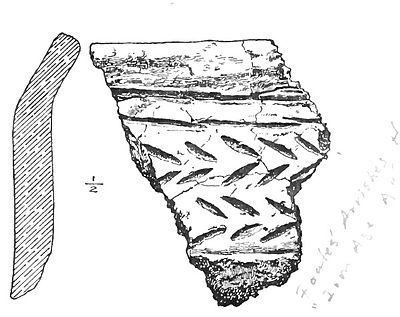

Fragment of Pottery.

nails. She is long ago gone to dust, and her dust dispersed, but the impress of her nails remains.

This is much like what we are all doing, and doing unconsciously—leaving little finger-touches on our creations, giving shape to the minds and habits of our children and of those with whom we are brought into contact, shaping, adorning, or disfiguring our epoch, and the impressions we leave are indelible; they will in turn be transmitted to ages to come.

Some of the ornamentation, as in a specimen from Smallacombe Rocks, is made with a twisted cord. The pottery is all hand-made, shaped without the wheel, and very imperfectly burnt. It is not red, because there was little iron in the clay.

One large hut at Foale's Arrishes had a seat carried round part at least of the interior, made of branches that were held from spreading by sharp stones planted upright in the floor. The kitchen was on the left side of the entrance in a subsidiary structure.

It has, of late, become a thing not unusual for young fellows, if suffering from delicacy of the lungs, to rent or buy a farm on Dartmoor. No research after parasitic microbes thenceforth concerns them. The fresh air, the constant exercise, the joyous existence on the wild moor are fatal to tubercular bacteria. Rude health, buoyant spirits, unflagging energy result from such treatment.

It is, it must be admitted, surpassing hard to induce servants from the "in-country" to take situations on Dartmoor. The air there is as unsuited to them as to other microbes. But the settler lights his own fires, cooks his own meals, makes his own bed; and, as one of them assured me, his experience proved to him that a man can keep a hunter at the same cost as he can a servant-maid: therefore, why be worried with the latter?

At Post Bridge they have had a succession of curates who have lived this life in cabins or hovels, and have learned to love it. It has one drawback, and one only—it makes the hands rough and grimy. But what are gloves for, but to cover dirty hands when we go to town to make display?

As to food. Rabbits are to be had at any moment; geese, ducks live and luxuriate on the moor; an occasional blackcock or moorhen and a brace of snipe give zest; and trout are to be obtained for the labour or pleasure of angling for them. The price of horses is mounting; any number may be grown on the moor. Sheep, cattle—you turn them

Ornamented Pottery.

out, and they thrive on the sweet grass, and know not the maladies that afflict flocks and herds in the world twelve hundred feet below.

Let it hot be supposed that in winter Dartmoor is a desolation and a horror. It is by no means an unpleasant place for a sojourn then. When below are mud and mist, aloft on the moor the ground is hard with frost and the air crisp and clear. Down below we are oppressed with the fall of the leaf, affecting us, if inclined to asthma and bronchitis; and in the short, dull days of December and January our spirits wax dark amidst naked trees and when our ankles are deep in mud. There are no trees on Dartmoor to expose their naked limbs, and tell us that, vegetation is dead. The shoulders of down are draped in brown sealskin mantles—the ling and heather, as lovely in its sleep as in its waking state; the mosses, touched by frost, turn to rainbow hues. For colour effects give me Dartmoor in winter.

And then the peat fires! What fires can surpass them? They do not flame, but they glow, and diffuse an aroma that fills the lungs with balm. The turf-cutting is one of the annual labours on the moor. Every farm has its peat-bog, and in the proper season a sufficiency of fuel is cut, then carried and stacked for winter use. I may be mistaken, but it seems to me that cooking done over a peat fire surpasses cooking at the best club in London. But it may be that on the moor one relishes a meal in a manner impossible elsewhere.

Widdecombe-in-the-Moor is a village in a valley walled off from the world by high ridges on the east and on the west. The entire bed of the valley has been washed and rewashed by streamers for tin. Bag Park is a gentleman's seat laid out on this collection of refuse, and the pines and firs luxuriate in the granite rubble and grow, as if it were to them a pleasure to thrust up their leaders and expand their boughs.

I shall never forget a drive through Widdecombe one October day, when the sun was shining bright, and the air was soft. The sycamores had shed their leaves; but the expedition was one through coral land. The rowan or mountain-ash, which was everywhere, was burdened with clusters of scarlet berries, and the hedges were wreathed with rose-hips and dense with ruddy haws.

The church of Widdecombe has a very fine tower, built, it is said, by the tinners. The roof has many of the original bosses, carved and painted with heads, flowers, and leaves. One has the figure on it of S. Catherine with her wheel. One boss has on it three rabbits, each with a single ear, which unite in the centre, forming a triangle. One exactly similar is in Tavistock church.

Part of the lower portion of the roodscreen remains with figures of saints on it.

The story of the great thunderstorm in which Widdecombe church was struck, on Sunday, October 21st, 1638, when the congregation were present at divine service, has often been told, notably by Mr. Blackmore in his novel Christowel.

Prince, in his Worthies of Devon, thus narrates the circumstances:—

"In the afternoon, in service time, there happened a very great darkness, which still increased to that degree, that they could not see to read; soon after, a terrible and fearful thunder was heard, like the noise of so many great guns, accompanied with dreadful lightning, to the great amazement of the people; the darkness still increasing, that they could not see each other, when there presently came such an extraordinary flame of lightning, as filled the church with fire, smoak, and a loathsome smell, like brimstone; a ball of fire came in likewise at the window, and passed through the church, which so affrighted the congregation, that most of them fell down in their seats; some upon their knees, others on their faces, and some one upon another, crying out of burning and scalding, and all giving themselves up for dead. There were in all four persons killed, and sixty-two hurt, divers of them having their linen burnt, tho' their outward garments were not so much as singed. . . . The church itself was much torn and defaced with the thunder and lightning, a beam whereof, breaking in the midst, fell down between the minister and clerk, and hurt neither. The steeple was much wrent; and it was observed where the church was most torn, there the least hurt was done among the people. There was none hurted with the timber or stone; but one man, who, it was judged, was killed by the fall of a stone."

The monument of this man, Roger Hill, is in the church, as also an account in verse of the storm,

composed by the village schoolmaster.

For many years the incumbent of Widdecombe was a man who was reputed to be the son of George IV. when Prince Regent. His sister, married to a captain, who deserted her, occupied a cottage, now in ruins, under Crockern Tor. She also was believed to be of blood-royal with a bar sinister. Both the parson and his sister had been brought up about Court. He, when given the living of Widdecombe—to get him out of sight and mind—brought with him a large consignment of excellent port, and that drew to his parsonage such rare men as would brave the moors and storms for the sake of a carouse.

His sister, in the desolate cottage under Crockern Tor, languished and died, leaving her only child, Caroline, to the charge of her uncle. She was sent for her education to a famous school in Queen's Square, London, where she associated with girls belonging to families of the first rank.

A certain air of distinction, as well as the story that circulated relative to her mother's origin, made her an object of interest, and her imperious manner commanded respect.

The vicarage was by no means a good place in which a young girl should grow to maturity. The house was not frequented by men of the best character, and the wildest stories are told of the goings-on there in the forties and fifties.

Caroline was, however, a girl of exceptionally strong character; she was early called on to hold her own with the associates of her uncle and frequenters of the vicarage, and she was quite able to enforce upon them a proper behaviour towards herself.

Unhappily, she had been reared without any religious principles; her law was consequently her own caprice, fortunately held in check by a strong sense of personal dignity.

The position she was in was as forlorn and unpromising as any in which a young girl could find herself.

She was full of generous impulses, but they were wholly untrained; she possessed furious passions, which were held in check solely by her pride. She would do at one time a generous act and next a dirty trick, "just," as the people said, "as though she were a pixy."

A gentleman named Darke, visiting her uncle on some business, married Caroline, and soon after her uncle died suddenly, having made a will in her favour.

The vicarage was well furnished and contained articles of great value, in pictures, plate, etc., supposed to have been presented to him, but most likely obtained with money lent at Court to those temporarily embarrassed.

The manor had been sold, and was purchased by Mrs. Darke's trustees at her request, and from that time she insisted on being entitled "Lady" Darke; and into this she moved with her dogs, horses, and husband.

This latter had soon discovered what an imperious character she possessed. His will might clash with hers, but hers would never give way. Her character was the toughest and most energetic, and by degrees he fell into a condition of submission and insignificance which it was painful to witness, and which "Lady" Darke herself resented, without being aware that it was due to her own overbearing behaviour.

She kept nine or ten horses in her stables—some had never been broken in; some she rode on, others were driven in pairs. But towards the end of her life the horses were not taken out, and ate their heads off many times over.

If a visitor of distinction was expected, she sent for him her carriage and pair with silver-mounted harness. For ordinary use she employed her brass-mounted harness; but Bill, her husband, was despatched to market in the little trap in which she fetched coals. Latterly Mr. Darke was sent to make purchases at Ashburton, with a long list of "chores," i.e. of articles he was to bring back with him, written out during the week on a slip of paper from a pocket-book. Here is one: "Kidney-beans and cucumbers; tea, and green paint with driers; brushes and putty; sweets; and a frock-body for myself; a milkpan, fourteen inches; side-combs, 3s. 6d.; ostler's boy and fish; lavender; pain-killer; wine, salad oil, harness paste, and rice; also ribs of beef, grate for blue bedroom, india-rubber; rabbits, grind scissors, cheese, inn and ostler."

She ruled her husband, and indeed everyone with whom she came in contact. He, cut off from social intercourse with his fellows, out of the current of intellectual life, with no other work to do than to fulfil her behests, sank in his own estimation, and fell into degradation without making an effort to rise out of it.

An instance of her despotic character may be given. One day she wanted to have her hay made; she was anxious lest a change of weather should come on. She issued an imperious order to the curate of the parish to come and help save the hay. He sent an apology. This rendered her furious. She went in quest of him, met him in the village, and falling on him soundly boxed his ears in public.

She was an implacable hater; and living on the wilds, half educated, she was superstitious, and believed in witchcraft, and in her own power to ill-wish such individuals as offended her. She was caught on one occasion with a doll into which she was sticking pins and needles, in the hope and with the intent thereby of producing aches and cramps in a neighbour. On another occasion she laid a train of gunpowder on her hearth, about a figure of dough, and ignited it, for the purpose of conveying an attack of fever to the person against whom she was animated with resentment.

It need hardly be said that believing in her own powers others believed in them as well, and dreaded offending her.

She was kind-hearted, and impulsive in her generosity. She divided the parish into two halves—one she gave over to the doctor and kept the other to herself. "He kills with his physic," she said, "I keep alive and recover with my soups and port wine."

She was vastly angry with the vicar, her uncle's successor, about some trifle, and she went after him with her whip and threatened to chastise him with it. He actually summoned her, and swore that he lived in bodily fear of the lady.

She liked to have visitors drop in on her, but not to be warned of their coming; for she took a pride in showing what she could provide for table on the spur of the moment; and forth would come a ham, half a goose, a boiled leg of mutton, a big cheese and celery, produced as by magic, and would be served by herself in an old gown, red turnover handkerchief on her shoulders, and a coalscuttle bonnet on her head.

Mrs. Darke at one time played on the piano after the meal to get her guests to dance, but the cats tore the instrument open and made their nests and kittened among the strings, and the damp air rusted the wires. Then she bought a barrel-organ, and forced her husband to turn the handle in the corner and grind out the music for the dancers. However, on one occasion, having tasted too often a bottle within reach, though out of sight, he fell forward in the middle of a dance and brought the instrument down with him. The instrument was so broken that it could no longer be used. Mr. Darke died at last in one of the fits to which he was liable, having retired to rest by mistake under in place of on the bed.

By this time the lady had become very deaf.

On hearing the news of the decease some friends went to see her.

"Very grieved, madam, at your sad loss!"

"Ah! Bill is dead. He might have done worse; he might have lived. You will stop and dine, of course."

They had to tarry to see to matters of business. "Now, look here," said "Lady" Darke, "I'll have no more 'truck' with Bill. He has been trouble to me long enough. I shall send him to his friends in Plymouth. Let them bury him."

"Madam," said the nurse, "we want to lay him out. Will you give me a sheet?"

"A sheet! One of my good linen sheets! Not I. Take a pig-cloth"; that is to say, one in which bacon was salted. And actually her husband was laid in his coffin in one of these "pig-cloths."

In Mrs. Cudlip's novel, She Cometh Not, He Saith, is a description of a meeting with the lady that is very true to life, as is also the account of the downstairs arrangement of the manor house.

In later years "Lady" Darke became infirm. She neglected everything, and no one dared do anything in the house without her orders. Until she came downstairs in the morning there could be no breakfast, as she kept the keys. The house was infested with cats and dogs, and her servants did not dare to get rid of any of them, or to drive them out of the rooms. The large room over the kitchen she alone entered. The door was padlocked, and the key of the padlock she kept attached to her garter. Thence the key had to be taken after her death to obtain admission. It was found to contain a confused mass of sundry articles to the depth of three feet above the floor, the accumulation of many years. Bureaus were there with guineas and banknotes in the drawers, and quantities of old silver plate, bearing the arms and crests of men of title who had been about the Court of the Prince Regent; and the whole was veiled in cobwebs that hung from the ceiling so long and so dense as to hide the further extremity of the chamber.

"Lady" Darke retained her imperious disposition to the end; it was in vain that it was suggested to her that she should have an attendant to be always with her. She often sat up the whole night by her fire, and her servants dared not retire to bed till their mistress had given the signal that they were to depart.

Of relations she had none; at least none who came near her, and when she was dead much difficulty was found in discovering any persons who had claim to her inheritance.

She died quite suddenly, and left no will.

Her trustees had to advertise before they could find relations, and then those who presented themselves were the children of her father by a third wife. Her dogs and cats were first killed, then several old horses that were dragging themselves about the field in extreme old age.

Her plate and pictures were sold.

To the best of my knowledge no portrait of her remains.

She was a fine woman, and must at one time have been handsome. It was fancied by many that her features bore a resemblance to the pictures of George IV. in his young days. The mystery relative to her mother and uncle was never solved, and it is possible enough that the supposed paternity was due to idle gossip.

There were vast collections of letters among the remains, but these were all destroyed, and nothing was allowed to transpire as to their contents.

The story from beginning to end is one of infinite sadness. It is of one with a remarkably strong but undisciplined character, one full of good impulses, who had never been taught religious duty, and given no religious belief, who was therefore condemned to waste a profitless life in a remote village, without purpose, without self-discipline, without hope, without God.

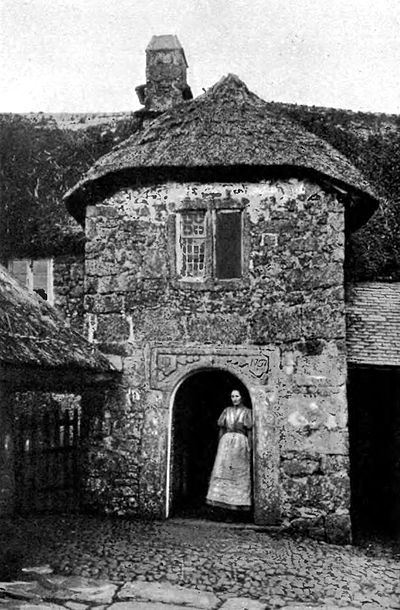

There are some interesting old farmhouses about Widdecombe; one is at Chittleford, another on Corndon. The primitive type of farm on the moor was an inclosed courtyard, entered through a gate. Opposite the gate is the dwelling-house, with a projecting porch, with an arched granite door and a mullioned window over it. On one side of the entrance is the dwelling-room, on the other the saddle and sundry chamber. The well, which is a stream of water from the moor conducted by a small leat to the house, is under cover; and the cattle-sheds open into the yard, so as to be reached with ease from the house without exposure to the storms.

These farm dwellings are rapidly disappearing, and are making way for more pretentious and extremely hideous buildings. Such as remain are remarkably picturesque, and should be photographed before they are destroyed.

Widdecombe must not be quitted without a reference to the famous ballad of the old grey mare taken there to the fair; a ballad that is immensely popular in Devon, and one to the air of which the Devon Regiment went against the Boers.

"Tom Pearce, Tom Pearce, lend me thy grey mare,

All along, down along, out along, lee.

For I want for to go to Widdecombe Fair,

Wi' Bill Brewer, Jan Stewer, Peter Gurney, Peter Davy,

Dan'l Whiddon, Harry Hawk,

Old Uncle Tom Cobleigh and all.

Chorus—Old Uncle Tom Cobleigh and all.

"And when shall I see again my grey mare?

All along, down along, out along, lee.

By Friday soon, or Saturday noon,

Wi' Bill Brewer, etc.

Lower Tarr

"Then Friday came, and Saturday noon,

All along, down along, out along, lee.

But Tom Pearce's old mare hath not trotted home,

Wi' Bill Brewer, etc.

"So Tom Pearce he got up to the top of the hill

All along, down along, out along, lee.

And he seed his old mare down a-making her will,

Wi' Bill Brewer, etc."

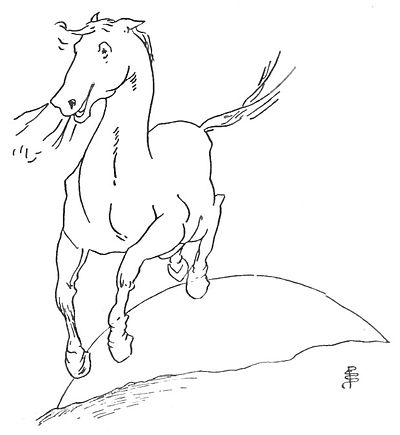

Now it does not appear from the song why the mare was so dead beat. But a clever American artist, who has illustrated the song, has brought her knowledge of human nature to bear on the story. She has shown in her pictures how that the borrower of the horse met with a pretty gipsy girl at the fair, and persuaded her to ride away with him en croupe. This explains at once why the horse was so overcome that it "fell sick and died."

One can understand also how that this ballad being a man's song, a veil is delicately thrown over this incident.

I do not quote the entire ballad.

"When the wind whistles cold on the moor of a night,

All along, down along, out along, lee.

Tom Pearce's old mare doth appear ghastly white,

Wi' Bill Brewer, etc.

"And all the long night be heard skirling and groans,

All along, down along, out along, lee.

From Tom Pearce's old mare in her rattling bones,

Wi' Bill Brewer, etc."

- ↑ See my article on "Foundations" in Strange Survivals (Methuen and Co., 1892). See also my Book of the West, i. p. 331.