CHAPTER V

ON WOOD-ENGRAVING IN ITALY IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

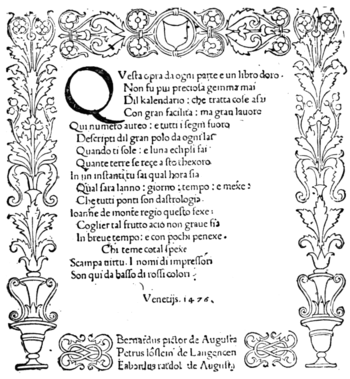

Although at this time Germany took the lead of all European countries so far as the illustrations of printed books are concerned, the transition from German to Italian art is like the change from the strong bleak winds of the North to the balmy air and sunny skies of the South. We are aware of the difference both of climate and of art in a moment: the very first picture presented to us reveals it. The Italians of the fifteenth century could not take up a handicraft without making it a fine art. Here is a title-page of a folio Kalendario produced in Venice in the year 1476. This is the first title-page on which the contents of the book, the name of the author, the imprint of the publishers, who were also the printers, and the date of the issue of the book, were ever given. Mark the decoration. Though the publishers were Germans, the artist who drew this border must have been an Italian; and probably the engraver was an Italian also, for the book was produced at Venice. The character of the design suggests the work of an illuminator. The introduction of the printing-press must have interfered sadly with the writer of manuscripts and his brother the illuminator, and both were doubtless glad to avail themselves of the new art. The manuscript writer may have turned compositor, and the illuminator may have been transformed into a book decorator.

TITLE-PAGE OF A FOLIO KALENDARIO BY JOANNE DE MONTE REGIO, PRINTED AT VENICE IN 1476 (much reduced)

We have before us a facsimile of a cut called 'The Triumph of Love,' which appeared as one of the illustrations of Triumphi del Petrarca, a book printed in Venice, in 1488. A man, seated with his hands bound behind him, is tied with a rope to a triumphal car which is drawn by four horses; on a ball of fire, which rises from the car, a blindfolded Cupid is shooting an arrow (apparently at the near leader); a great crowd of men and women, among whom we see a king and a mitred bishop, follow and surround the car, and on a distant hill we behold Petrarch conversing with his friend. There are two rabbits feeding calmly in the foreground, notwithstanding the danger of the horses' hoofs, and the usual conventional designs for grass and flowers. The groundwork of the border of this curious print is black, with an Italian design carefully cut out in white, with but little shadow. From the waviness of many of the lines which should be straight, we think this print must be from an engraving on metal.

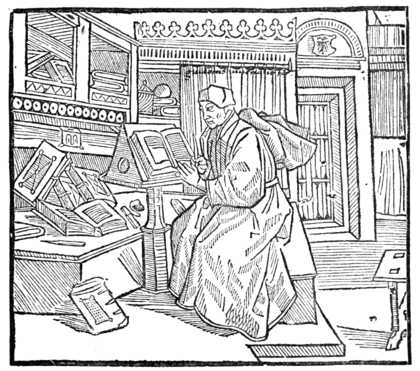

Of all the wood-engravings executed in Italy in the fifteenth century, none can compare in excellence with those in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (Dream of Poliphilo) printed in Venice, by Aldus, in 1499.[1] There are, in all, one hundred and ninety-two subjects, of which eighty-six relate to mythology and ancient history, fifty-four are pictures of processions and emblematic figures, thirty-six are architectural and ornamental, and sixteen vases and statues. They have been attributed to many different artists, the most probable of whom is Carpaccio. The subject of the 'Hypnerotomachia' has been described as a 'Contest between Imagination and Love'; it is a curious medley of all kinds of fable, history, architecture, mathematics, and other matters, seasoned with suggestions which do not reflect credit on the moral perceptions of its author, a Dominican monk, named Francesco Colonna. An enthusiastic admirer of this book thus poetically describes it: 'There is, perhaps, no volume where the exuberant vigour of that age is more clearly shown, or where the objects for which that age was impassioned are more glowingly described.

POLIPHILO IN THE GARDEN

From 'Hypnerotomachia Poliphili,' printed by Aldus at Venice in 1499

The romantic and fantastic rhapsody mirrors every aspect of nature and art in which the Italians then took delight—peaceful landscape, where rivers flow by flower-starred banks and through bird-haunted woods; noble architecture and exquisite sculpture, the music of soft instruments, the ruins of antiquity, the legends of old mythology, the motions of the dance, the elegance of the banquet, splendour of apparel, courtesy of manners, even the manuscript, with its cover of purple velvet sown with Eastern pearls—everything that was cared for and sought in that time when the gloom of asceticism lifted and disclosed the wide prospect of the world lying, as it were, in the loveliness of daybreak.' But it is more on account of the beauty of the cuts than the poetry of the author that this book has been so much admired and so frequently reprinted. Our illustration shows us where Poliphilo in his dream visits a bevy of fair maidens in a garden. These nymphs are not very beautiful, but, though they have such high waists, remark how gracefully their figures are drawn, and look at the action and the drapery of the damsel running away. The engraving is, without doubt, an exact facsimile of the artist's drawing; the lines are clear and crisp, and are evidently the work of a practised hand. The drawing of the gateway and trees is simply conventional. We are sorry that we have not room for more of the illustrations of this remarkable work.

In these early books it seems to have been nobody's business to record the name of the engraver who produced the illustrations, and, although the printer's name is generally very conspicuous in the colophon, the artist's name rarely, if ever, appears. But the work of certain masters of certain schools is generally recognised with ease, either by some peculiarity of manner, or by some particular mark. Thus one artist, who, towards the end of the fifteenth century, illustrated a few books printed in Italy, is known as 'the master of the dolphin,' because in most of his work this fish appears among the decorations. Another is known to us only by the name of 'the illustrator of the "Poliphilus,"' that quaint romance of Colonna which has taken a proud place in literature, not for its own intrinsic merits, but rather on account of the beauty of its woodcuts, the name of whose author is still a matter of conjecture.

We may here say a few words about Aldo Manuzio, better known in England by his Latinised name, Aldus Manutius, the celebrated printer, and some of the other early printers of Venice. One of the first to set up a press in Venice was Nicolas Jenson, a Frenchman, who had worked at Mentz, and who was the first to cut and introduce Roman type such as is now in use. At his death his business and plant were bought by a rich man, Andrea Torresano, of Asola, and the work was carried on successfully. Aldo Manuzio, who was born at Sermoneta, a village near Velletri, in 1450, received an excellent education, especially in Greek; and the celebrated Pico da Mirandola made him tutor to his nephews, Alberto and Leonardo Pio, Lords of Carpi. Alberto Pio, under his master's training, became a great lover of literature; and when Aldo conceived the idea of starting a printing-press, the young lord advanced him the necessary funds, and gave him a house in Venice near the Church of Sant' Agostino. Aldo then married a daughter of Torresano, and the two printing businesses were joined and carried on together under Aldo's direction. His house, we are told, was a veritable colony; besides the compositors' rooms and the press-rooms, he had closets for press-readers and studios for the special use of learned authors. The first 'printer's devil' was a little negro boy who had been brought by one of the men from Greece.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century the wood-engravers of Florence were celebrated for beautiful book illustrations in a distinct style. Those in the Quatro Reggie, Florence, 1508, are typical examples; their chief characteristics are, great breadth; masses of white and black evenly balanced; and the frequent use of white lines out of masses of black.

TEOBALDO MANUZIO—KNOWN AS ALDUS, PRINTER AT VENICE

Some of the fine borders to these early Italian wood-engravings owe their distinctive character to earlier work of engravers on metal. Thus the borders round the illustrations of the Venice folio of 1491 of the Triumphs of Petrarch seem to be direct copies of engravings in metal by Filippo Lippi. The masses of white on a black background are very effective, and the strength of the colour increases the effect of the picture which the border surrounds.

Between 1474 and 1512 Aldus printed for the first time the works of thirty-three Greek authors. The works of Aristotle, brought out in four volumes, occupied three years. A learned Greek, Musurus of Crete, corrected the proofs, in which Aldus himself assisted. The workmen were nearly all Greeks. The Greek type was copied from the handwriting of Musurus, and the Italian, known as the Aldine, from the writings of Petrarch; this was cut by the celebrated artist-goldsmith, Francia of Bologna. The Aldine edition of Virgil (1501), now exceedingly rare, was the first book printed in this Italic type. Notwithstanding all his learning, energy, and philanthropy, Aldus did not succeed in his business. Many of his books were pirated, wars and insurrections interrupted him, the League of Cambray caused him to close his works from 1506 to 1510, and he sold his books at a rate too cheap to be remunerative.

The first printed edition of Æsop's Fables, which appeared at Verona as early as 1481, and was reprinted at Venice in 1491, contains many excellent engravings inclosed in ornamental borders, thoroughly Italian in character. The figures are not unlike those in the 'Hypnerotomachia,' and we can readily imagine that they were drawn by the same artist, who has given us little more than outlines, which the engraver has well cut in facsimile. The fable of 'The Jackdaw and the Peacock' is particularly well done. An edition of Ovid's Metamorphoses appeared also at this time with tolerably good illustrations not so well engraved.

There are some curious little cuts in the Epistole di San Hieronymo Volgare, published in Ferrara in 1497, which are more valuable for their originality than their beauty, either of drawing or engraving. The book was evidently intended for the use of the illiterate, to whom the quality of the pictures laid before them was of little consequence if they told the story that was meant for them to read with their eyes. The homely scene of Christ appearing like a Gardener with a hoe on His shoulder, addressing Mary Magdalene in an Italian pergola, would appeal to their feelings much more directly than the Transfiguration of Raphael.

A BOOTMAKER'S SHOP

From the 'Decameron,' printed in Venice in 1492

We do not find record of any other important wood-engravings in the history of printing in Italy at the end of the fifteenth century. Presses abounded everywhere, chiefly managed by Germans; there was scarcely an important town in Italy without a printer; few illustrated books, however, were issued at this time. An edition of Boccaccio's 'Decameron,' with many excellent cuts, one of which, representing a bootmaker's shop, we give as an illustration, was printed by the brothers Gregorio at Venice in 1492. And there are some illustrations in a book called 'Fiore di Virtù,' which appeared in Venice in the same year, that may be praised for the work of the wood-engraver, though the designer shows a sad ignorance of the laws of perspective and proportion. And we have before us an illustration to a poem by Poliziano, in which Giuliano dei Medici is kneeling before the altar of the goddess Minerva, where we see graceful drawing by the artist and fairly good engraving. It was printed in Florence, but the type bears no comparison with the beauty of the Aldine books.

FRONTISPIECE TO A 'TERENCE,' PRINTED AT LYONS IN 1493

The love of colour, which is born in all Italians, led them to develop a process of making pictures in chiaroscuro—by printing several wood-blocks one upon another, each block giving a separate tint. In fact, it was the beginning of the modern colour-printing. The invention of the new process was claimed by Ugo da Carpi, who reproduced several of the designs of Raphael. In the beginning of the next century we find pictures printed in four different colours—trying to imitate water-colour, or, rather, distemper drawings. (See p. 99.)

At Lyons, about the same time, there was an illustrated edition of 'Terence' published, with well-executed woodcuts, from which we are able to give only the frontispiece, 'The Author writing his book.' It is sufficient to show that the engraving is the work of a practised hand.

- ↑ An English version, neither faithful nor complete, was published in the time of Queen Elizabeth, 'At London, Printed for Simon Waterson, and are to be sold at his shop in St. Paule's Churchyard at Chepegate, 1592.' It is extremely scarce. Many of the pages, as giving examples of costume, have lately been reprinted by authority of the Science and Art Department. There is a French edition of Poliphilo, printed at Paris by Kerver in 1561, with illustrations in a late florid French style.