CHAPTER V.

THE VOLCANOES.

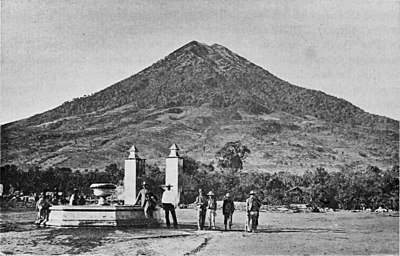

On the afternoon of the 8th of January we started with all our men and mules, carrying bed, tent, canteen, and provisions, for the Indian village of Santa Maria, about three leagues distant on the slope of the volcano.

Our road lay through the streets of the old town, past ruined churches and half-neglected convent-gardens, then through an alameda with a beautiful avenue of ficus trees whose branches met overhead, to a picturesque old fountain at the southern outskirts of the town, where the country people were resting and watering their beasts. Here we, too, came to a halt, more to gratify the social instincts of our mules than for any other reason.

After leaving the fountain we began the very gradual ascent of the lower slope of the mountain, and at each turn in the road our eyes were charmed by lovely glimpses over coffee fincas and gardens full of flowers and flowering trees to the white walls and church towers of the old town below us slightly veiled in a summer mist.

ANTIGUA, A RUINED CHURCH. We passed a village with a massive white church and stone-flagged plaza, and then on again through Indian gardens of coffee-trees and bananas and great spreading Jocote trees, bare of leaves, but laden with the yellow and crimson fruit with which the Indian flavours his favourite intoxicating chicha.

As we slowly rode into Santa Maria the shadows of evening were falling, and out of the great stillness the sound of bells ringing the "oracion" rose from the distant villages of the plain, bringing with it that indescribably peaceful mood which penetrates the soul of the wanderer in whatever clime, when the labour of the day is done and he hears the call of the faithful to prayer. Passing through a miserably dirty village street, we entered by a pretentious gate into the great bare plaza. A huge ugly church faced us, and to the left stretched the long low cabildo. The other two sides of the plaza were intended to be closed in by high walls, and by the gateway through which we had entered; but these were additions which the Indian mind clearly deemed superfluous, for the gateway was without a gate, half the west wall had fallen down, and the south wall had not been built. Outside this great square the town was almost wholly composed of thatch-roofed native huts.

The life of the village centered round the fountain which stood in the middle of the plaza. Here party after party of women with babies slung on their backs or astride on their hips, and strings of children running at their heels, came to fill their "tinajas" and carry home the water for the night's consumption. The habit of carrying heavy burdens on their heads gives them a good bearing and a free gait, which is the only attraction they possess, for a dirtier or more hideously ugly female population it would be difficult to find. There is, however, this to be said for them, that they were sober and could attend to their household duties, whilst the men almost without exception were drunk with chicha; and my husband and Gorgonio, both of whom had been here several times before, assured me that they had always found them in the same condition.

The Alcalde at Antigua had kindly recommended us by letter to the ladino "Secretario" of the village (the official appointed by the government to keep the Indian Alcalde and his subordinates in the straight path), who showed us every possible attention, placed the Sala Municipal entirely at out disposal, and, most important of all, promised us that Indian carriers should be ready to accompany us on the morrow.

The Cabildo was really a sound good building, and the apartment allotted to us was sumptuously furnished with two or three large tables, a cupboard containing the Municipal papers, several chairs of doubtful strength, and a strong box holding the public monies. We considered ourselves vastly well accommodated, with plenty of room to stretch out our beds, and a table upon which to eat the supper which our men were preparing for us over a fire they had made in the plaza.

The only person who looked unhappy was the old Indian who had charge of the public treasure; he glanced at us askance and every few minutes would enter the room and walk up to the chest to see that it was all right, until finally he spread his mat right across the doorway, so that no one could enter, and lay down to sleep. We were glad to turn in ourselves and to close the windows and doors, which shielded us from the unpleasantly close proximity of a party of travelling Indian merchants who had taken up their quarters for the night in the verandah.

It was in the early glimmer of dawn when we were awakened by the movements of our neighbours, who shouldered their cacastes and set out thus betimes on their journey. So, following their good example, we folded up our beds and prepared for an early start, hoping to reach the summit of Agua by noon. But, as usual, the cargadores who had been summoned by the public crier the night before failed to appear—some sent excuses, some arrived late, and others did not come at all, and nearly all the precious cool hours of the morning had slipped away before the Secretario had caught the truants, who were already half drunk, and the burdens had been arranged to suit their tastes. The tent-poles were vehemently protested against by the man selected to carry them, and I must own that my sympathies were with him, for he was a diminutive specimen of a race short in stature, and the tent-poles were five feet long. I longed to be able to sketch our cargadores as they shouldered their loads and trotted off up the mountain, each with his head tied up in a dirty red handkerchief, his long knife or machete in hand, and a packet of tortillas and a gourd full of chicha made fast to his cargo.

It is a long gradual ascent of about 5000 feet to the summit. The path has been well made and nowhere are the grades uncomfortably steep. The day was lovely, in the open places a cool breeze fanned us, and in the shelter of the woods no breeze was needed for the temperature was perfect.

At first our path lay through scrubby woods of recent growth, and then through cornfields and through peach-orchards with the trees in full bloom, and higher still we rode through patches of potatoes planted beneath the shade of the forest trees. Elder bushes full of powdery white blossoms reminded us of home; on either side of the way the banks were bordered by masses of flowers and ferns and charming green things of various kinds. There were great natural plantations of sunflowers and scarlet salvias, wild geraniums, fuchsias, and cranes' bills, and other innumerable small and bright blossoms nestled away amongst the ferns and foliage.

The many windings of the path brought us continually in sight of charming bits of scenery. Sometimes the mass of Fuego loomed up in front of us, framed by branches of trees and exhibiting the usual display of varying cloud effects, then again the eye rested on the glistening white houses of Antigua, and as we rose higher other and more distant towns and villages came into view.

The path would have indeed been good but for the activity of the "taltusas" or gophers (Geomys hispidius), who had so undermined it as to make it positively dangerous. Into the numerous hidden pitfalls horse and mules continually floundered with much discomfort and some danger to the riders. Twice I saw our boy Caralampio pitched right over his mule's head, the mule losing both his fore legs in a burrow, but luckily both boy and mule escaped unhurt. My mule, with singular cleverness and care, avoided every hole and suspicious-looking place, whilst the horse, with equally exceptional stupidity, floundered into them all. On one occasion, choosing for the performance the steepest and narrowest place in the path, right on the edge of a precipice, he managed, first to lose his fore legs in a burrow, and nearly to crush his rider's leg against a projecting rock, then in struggling out to lose both his hind legs in another burrow, and to finish up by falling over backwards. My mule, who was following close behind, seeing horse and rider rolling down the hill together, whipped suddenly round, and started off at a more lively pace than I was accustomed to. Luckily Gorgonio, ever on the alert, caught at her bridle as she passed him, and no more damage was done beyond the breaking of the bit. My husband was soon on his feet again unhurt, and so was the horse, and we were all heartily thankful to have escaped what might so easily have been a serious accident.

We next passed through a belt of large velvety-leaved trees (Cheirostemon platanoides); when we were rather more than halfway to the summit, deciduous trees and flowering shrubs came to an end, and we found ourselves amongst rough grass and pine-trees in the region of frost. Here, along the shady side of the path, one could see small cave-like recesses cut in the hill-side, which have a curious origin. The sloping surface of the soil is saturated with moisture slowly draining down the mountain-side, continually renewed by the clouds and mist which are ever gathering round the summit; every night this moisture is congealed into myriads of minute elongated crystals, which are so closely mixed with the disintegrated surface of the soil, that they almost escape notice. This mixture of earth and ice the Indians scoop out of these shady nooks and make into packages weighing about 170 lbs. each, neatly wrapped up in the coarse mountain grass, and one of these heavy packages an Indian will carry on his back for sale in Antigua or Escuintla; but now the manufacture of artificial ice is putting an end to his trade, and in another generation it will be extinct. In order to collect a sufficient quantity of this ice the Indians have to begin their work before sunrise, for although the sun does not actually shine on these hidden beds of crystals, the warmth of the day considerably diminishes the supply.

Our road zigzagged up the N.E. side of the mountain, and shortly after entering this region of frost we were enveloped in a cloud of mist, which shrouded us until the sun set. All the beauty went out of the evening; the air grew cold and damp, and as we neared the top, the altitude took effect on my lungs. Although I would have preferred to trust to my own feet on the difficult and almost dangerous path, I was wholly unable to do so, and had to sit my panting mule until we reached the lip of the crater, where I was obliged to dismount and scramble down on foot to the level ground at the bottom. With the exception of the one break in the rim through which we had clambered, the rugged and precipitous sides of the crater rose to a height of 300 feet all around us, and it would be difficult to imagine a gloomier or more inhospitable scene than this great dreary grass-grown bowl presented to our eyes in the waning light.

The Indians soon heaped together a good supply of pine logs and lighted large fires. The tent was hastily put up, and we worked hard to make ourselves comfortable before dark. The task was, however, only half-completed when the sun set, and the great black pall of night covered us, bringing a darkness that could be felt, which the fires seemed only to intensify. However, half an hour later the mist cleared away, and one by one the stars came out, clear and sparkling in the blue-black sky. Venus and a young crescent moon hung for a brief moment very near together on the edge of the crater and then left the black abyss colder and darker than before.

Hoping to divert my thoughts from this heavy darkness, which oppressed me almost to the point of physical pain, I turned my attention to the fire and my duties as cook. But here I met with an unexpected difficulty, for owing to the altitude everything boiled at a ridiculously low temperature, and the curried fowl I put on to cook spluttered and frizzled long before it was half-heated through; and although I put it back time after time, owing to the rapidity with which it boiled on the underside and cooled down on the upperside, we got no more than a comfortless and half-cold supper after all. Supper over, there was nothing left to do but to go to bed, and wrapping ourselves in all the rugs and coats we possessed, we tried to forget the cold and general discomfort in sleep, but our efforts were in vain. The temperature fell lower and lower, icy gusts of wind flew shuddering past the tent, shaking the canvas and stretching every rope, leaving an oppressive stillness behind almost more alarming than the blasts themselves At such moments one's nerves, already at full tension, became unmanageable, and one's mind conjured up fantastical pictures and forebodings of danger from the treacherous nature of the mountain to whose mercies we had confided ourselves: a mountain which I knew well enough, in the daytime, had not been in eruption within the memory of man. But perhaps the most uncomfortable feeling of all was the difficulty in breathing, and the unusual gasping sensation following the least change of position.

The Indians' habit of early rising was on this occasion a source of joy to me, and long before daylight the terrible freezing monotony of the night was broken by the sound of voices and the heaping together of the smouldering logs; it was a moment of joy when Gorgonio appeared with hot coffee and bread.

We were anxious to lose none of the beauty of the sunrise, and as soon as possible we began to climb the rough sides of the crater, a task involving many pauses and great expenditure of breath; indeed so painful was the effort to expand one's lungs, that at times one felt inclined to give up all further exertion. Gradually, however, the strain relaxed, and by the time we had reached the ridge we breathed normally, inhaling refreshing draughts of the purest and most invigorating air, and feeling fit for any further amount of scrambling.

Arduous as was the task of ascending to the rim of the crater it was as nothing compared with the difficulty now before me of attempting to describe the beauty of the scene on which we gazed. The world lay still asleep, but just stirring to shake off the blue-grey robe of night which had thrown its soft misty folds over lakes and valleys. A magnificent panorama of mountain-peaks floated out of the mist, east and west and north, whilst to the south a grey hazy plain stretched away until it was lost in the mists of the ocean. Following the line of the coast the great bulwark of volcanic cones stood shoulder to shoulder, and in the far east we could just catch the faint red light from the active crater of Izalco in Salvador reflected on the morning sky. One by one the lofty peaks caught, a pink glow from the coming sun, and as the mists rolled away we could see the pretty lake of Amatitlan nestled amongst the hills and the sleeping hamlets clotted over the plains. Very near to us on the west towered the beautiful volcano of Fuego, still clothed in the softest blue mist. As the sun rose clear and bright we beheld a sight so interesting and beautiful that it alone would have repaid us for the miseries of the night, for at that moment a ghost-like shadowy dark blue mountain rose high above all the others, and as we gazed wondering what this spectral visitor might mean, we saw that it was the shadow of Agua itself projected on the atmosphere, which moved as the sun rose higher and gradually sank until it lay a clear-cut black triangle against the slopes of Fuego. It was an entrancingly beautiful sight, and strange as it was beautiful. As the sun rose higher in the heavens and warmed the air we lay resting and basking in its light on soft beds of grass, marvelling in careless fashion over the wonderful changes we had witnessed, the contrast between the profoundly dark and tragic night and the laughing merry day, and we rejoiced that we had come to see the varying moods of nature at such an altitude.

Then we had a glorious scramble right round the edge of the crater, the highest point of which, as measured by Dr. Sapper, is 12,140 feet above sea-level; at last, regretfully tearing ourselves away from scenes of so much loveliness, we plunged down again to where our tent stood in the sunless crater in the middle of a grassy plain about one hundred and fifty yards across. Here we found Gorgonio occupied in thawing the coffee, which had frozen solid in the bottle since our early breakfast time. We were soon en route for Santa Maria, and I noticed a certain readiness amongst the Indians as well as our own men to escape from the crater, where we had passed so gloomy a night. Mindful of the holes and pitfalls in the path, we preferred to risk nothing, and walk the six miles to the village. On our way down we passed some of the Indian ice-gatherers staggering under their heavy burdens. It was past noon when we arrived at Santa Maria, and after a few hours' rest we mounted our mules and rode on in the cool of the afternoon, and reached Antigua before dark.

Note (by A. P. M.).—I had made two ascents of Agua previous to the expedition just described by my wife. The first was in January 1881, when I walked from Santa Maria to the crater and back in the day (for the mule-path had not yet been made), arriving at the summit at about 10 o'clock; on the way up I had passed through a belt of cloud which thickened and spread until the whole country seemed to be covered up with it. The sun was shining in a brilliantly blue sky overhead, and the top of the mountain stood out perfectly clear, like an island in a silver sea. It was an exquisitely beautiful sight looking down on the great mass of sunlit billows stretching to the horizon, but it was not what I had come to see, so after waiting for four hours I packed up my camera and compass and marched down again.

On New Year's day, 1892, I climbed up Agua again, and as it was fortunately a clear day I took a round of angles and some photographs.

During the next few days I made the acquaintance of Dr. Otto Stoll, who was then practicing medicine in Antigua, and collecting the valuable notes on the Indian languages which he has since published, and, to my great delight, I learnt that he wished to make the ascent of Fuego; so we arranged to start the very next day for the village of Alotenango. On the 7th January we left that village about 7 o'clock in the morning with seven Mozos, carrying food, clothing, and my camp-bed, and rode for an hour towards the mountains, when we dismounted and sent back our mules. The first two hours' climb was not so very steep, but it was tiring work walking over the loose mould and dry leaves under the thick forest. At 10 a.m. we stopped an hour for breakfast. Dr. Stoll was in very bad training, as he had been suffering from fever, and it needed all his pluck to face the hill at all. Then we recommenced our climb under shadow of the forest by a steep path cut through the undergrowth. At the height of about 9500 feet we, for the first time since starting, got a sight of the peak rising on the other side of a deep ravine. The whole of the slope on which we looked was bare of vegetation, and presented to the eye nothing but desolate slopes of ashes and scoriae broken higher up with patches of burnt rock; we scrambled on through the thick undergrowth, often with loose earth under foot, and by degrees the vegetation changed and we got amongst the pine-trees. At about 11,200 feet we came to a spot where the earth had been levelled for a few yards by the Indians, and there we determined to pass the night. I put up my bed, and the Mozos arranged a fence of pine-boughs to break the force of the wind, and collected wood for a fire. As we were all snug by about half-past four, I scrambled up a little higher to see what sort of view I could get of the Meseta and cone for a photograph, and then returned and watched the reflection of the sunset over the more distant peaks and against the perfect cone of Agua. It was a most beautiful sight, but the cold which followed the sunset soon took all our attention, and when I had turned into bed I had on three jerseys, two flannel shirts, and a loose knitted waistcoat under my cloth clothes, and my rug double all over; yet I felt the cold intensely, and poor Stoll, who was even better wrapped up than I was, was shivering, so we pulled down the waterproof sheet which we had rigged overhead and put it over both of us; still I was frequently awakened by the cold, and Stoll got, I fear, no sleep at all. The Mozos rolled up in their ponchos, with their toes to the fire, seemed to endure the cold much better than we did. We turned out of our shelter at about half-past four in the morning, and felt all the better after drinking hot coffee; we then sat for an hour watching a most beautiful dawn and sunrise. At the opposite side of the valley rose the Volcano of Agua, sloping on one side to the plain of Antigua, and on the other in a long unbroken sweep to the sea, more than forty miles away. Peak after peak stood out against the red light into the far distance, and on the right the low coast-line and the sea showed up very clearly.

As soon as the sun was up we started for the summit. I stopped on the

way to get a photograph of the cone, which lay to the left of us as we ascended; but the clouds came over just as I was ready, and I had to give it up. A little over 12,000 feet we left the scraggy pine-trees and arrived at the northern end of a cinder ridge, called the Meseta, which is at the summit of the slope we had been climbing. To the north of us, on the other side of

THE FIRE PEAK AND MESETA.

a deep rift, rose the distant cone of Acatenango, the highest of the three peaks of the mountain, covered with sparsely scattered pine-trees almost to the top; to the south, half a mile distant at the other end of the Meseta, rose the active cone of Fuego.

West from the Meseta was a most lovely view over a wooded valley, broken by cultivation, and dotted with villages to the slopes of Atitlan, the nearest to us of the long line of volcanoes which follows the coast-line and sweep in long wooded stretches to the sea. On the land side the slope of Atitlan dipped into the great lake which sparkled below us in the sunlight. Beyond the lake ridge after ridge rose abruptly in the distance. The wind came bitterly cold over us as we stopped to look at the view, and every now

PEAK OF ACATENANGO, FROM THE MESETA. and again the clouds shut everything from our sight; the Mozos huddled together under tufts of coarse grass, and, as we had been warned, refused to go any further. So we set out along the cinder ridge of the Meseta alone; it was just broad enough to walk along in safety, but a fall on the east side would have sent one headlong down a precipice, or on the west side sliding down steep cinder slopes, broken by smoking holes like half-formed craters, into the black forest-covered gullies below.

In a very high wind it would be impassable; as it was I only lost first one and then the other of my (double) Terai felt hats, whirled off my head by the sudden gusts. At the end of this ridge we came to the actual cone, more than 400 feet high, formed of small loose cinders and scoriae, as steep as the roof of a house. It was a terribly hard pull up. With the help of a strong stick, and often by using my hands and with many rests on the way, I at last reached some lava rocks where there was good foothold. Stoll was so weak from his fever that two or three times he told me that he must give up, but when he saw me getting on in front of him he plucked up courage and came on again. I had thought the ridge of rocks was round the crater itself, but after scrambling up them I found that there was still 40 or 50 feet above me of steep cinder slope, which luckily proved to be harder and gave better foothold than what we had already passed. Up this I climbed, and at the very top of the peak looked over into the crater on the sea-side. It was a hole about a hundred feet deep, almost surrounded by broken jagged and smoking rocks covered with sulphurous deposit and falling away on the further side to greater depths which projecting walls of rock hid from my view. I went back down to the ridge of rocks I had passed and shouted encouragement to Stoll, who was pluckily struggling on. Fortunately for me I suffered from none of the headache and heart-beating which had troubled me on the top of Agua the week before. Perhaps the most curious thing about the mountain is the fact that it rises quite regularly and gradually to a sharp point, on which the two of us could sit and get an uninterrupted view all round.

Once at the top Stoll was more venturesome than I, and induced me to follow him round the smoking edge of the crater to a projecting rock, a few yards to the left, but we did not greatly improve our view. The fumes from the crater were not very pleasant, but luckily the wind was in our favour. After a short rest on the summit we returned to the Meseta, shooting down the cinder slope as if it were snow, somewhat to the damage of our boots.

We got back to our camping-place about 11 o'clock, and after a good breakfast, started for the descent, and reached Alotenango between 4 and 5 o'clock in the afternoon.