An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans/Chapter 7

CHAPTER VII.

MORAL CHARACTER OF NEGROES.

"Fleecy locks and black complexion

Cannot forfeit Nature's claim;

Skins may differ, but affection

Dwells ill black and white the same.

"Slaves of gold! whose sordid dealings

Tarnish all your boasted powers,

Prove that you have human feelings,

Ere you proudly question ours."

The Negro's Complaint: by Cowper

The opinion that negroes are naturally inferior in intellect is almost universal among white men; but the belief that they are worse than other people, is, I believe, much less extensive: indeed, I have heard some, who were by no means admirers of the colored race, maintain that they were very remarkable for kind feelings, and strong affections. Homer calls the ancient Ethiopians "the most honest of men;" and modern travellers have given innumerable instances of domestic tenderness, and generous hospitality in the interior of Africa. Mungo Park informs us that he found many schools in his progress through the country, and observed with pleasure the great docility and submissive deportment of the children, and heartily wished they had better instructers and a purer religion.

The following is an account of his arrival at Jumbo, in company with a native of that place, who had been absent several years: "The meeting between the blacksmith and his relations was very tender; for these rude children of nature, free from restraint, display their emotions in the strongest and most expressive manner.—Amidst these transports, the aged mother was led forth, leaning upon a staff. Every one made way for her, and she stretched out her hand to bid her son welcome. Being totally blind, she stroked his hands, arms, and face, with great care, and seemed highly delighted that her latter days were blessed by his return, and that her ears once more heard the music of his voice. From this interview, I was fully convinced, that whatever difference there is between the negro and the European, in the conformation of the nose, and the color of the skin, there is none in the genuine sympathies and characteristic feelings of our common nature."

At a small town in the interior, called Wawra, he says, "In the course of the day, several women, hearing that I was going to Sago, came and begged me to inquire of Mansong, the king, what was become of their children. One woman, in particular, told me that her son's name was Mamadee; that he was no heathen; but prayed to God morning and evening; that he had been taken from her about three years ago by Mansong's army, since which she had never heard from him. She said she often dreamed about him, and begged me, if I should see him in Bambarra, or in my own country, to tell him that his mother and sister were still alive."

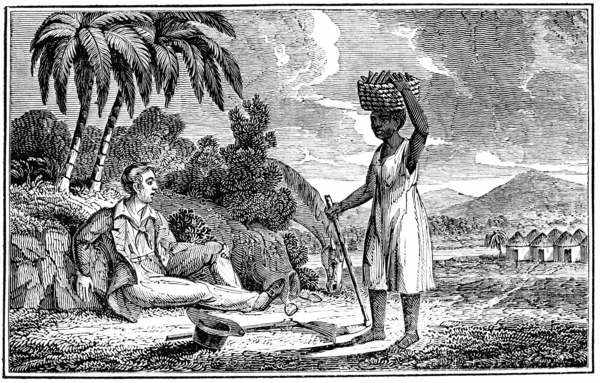

At Sego, in Bambarra, the king, being jealous of Mr Park's intentions, forbade him to cross the river. Under these discouraging circumstances, he was advised to lodge at a distant village; but there the same distrust of the white man's purposes prevailed, and no person would allow him to enter his house. He says, "I was regarded with astonishment and fear, and was obliged to sit all day without food, under the shade of a tree. The wind rose, and there was great appearance of a heavy rain, and the wild beasts are so very numerous in the neighborhood, that I should have been under the necessity of resting among the branches of the tree. About sunset, however, as I was preparing to pass the night in this manner, and had turned my horse loose, that he might graze at liberty, a woman, returning from the labors of the field, stopped to observe me. Perceiving that I was weary and dejected, she inquired into my situation, which I briefly explained to her; whereupon, with looks of great compassion, she took up my saddle and bridle

and told me to follow her. Having conducted me into her hut, she lighted a lamp, spread a mat on the floor, and told me I might remain there for the night. Finding that I was hungry, she went out, and soon returned with a very fine fish, which being broiled upon some embers, she gave me for supper. The women then resumed their task of spinning cotton, and lightened their labor with songs, one of which must have been composed ex-tempore, for I was myself, the subject of it. It was sung by one of the young women, the rest joining in a kind of chorus. The air was sweet and plaintive, and the words, literally translated, were these:

"The winds roar'd, and the rains fell;

The poor white man, faint and weary,

Came and sat under our tree.—

He has no mother to bring him milk;

No wife to grind his corn.

CHORUS.

"Let us pity the white man;

No mother has he to bring him milk,

No wife to grind his corn."

The reader can fully sympathize with this intelligent and liberal minded traveller, when he observes, "Trifling as this recital may appear, the circumstance was highly affecting to a person in my situation. I was oppressed with such unexpected kindness, and sleep fled from my eyes. In the morning, I presented my compassionate landlady with two of the four brass buttons remaining on my waistcoat; the only recompense I could make her."

The Duchess of Devonshire, whose beauty and talent gained such extensive celebrity, was so much pleased with this African song, and the kind feelings in which it originated, that she put it into English verse, and employed an eminent composer to set it to music:

And ah, no wife or mother's care

For him the milk or corn prepare.

CHORUS.

The white man shall our pity share;

Alas, no wife, or mother's care,

For him the milk or corn prepare.

The storm is o'er, the tempest past,

And mercy's voice has hush'd the blast;

The wind is heard in whispers low;

The white man far away must go;—

But ever in his heart will bear

Remembrance of the negro's care.

CHORUS.

Go, white man, go—but with thee bear

The negro's wish, the negro's prayer.

Remembrance of the negro's care.

At another time, Mr Park thus continues his narrative: "A little before sunset, I descended on the northwest side of a ridge of hills, and as I was looking about for a convenient tree, under which to pass the night, (for I had no hopes of reaching any town) I descended into a delightful valley, and soon afterward arrived at a romantic village called Kooma. I was immediately surrounded by a circle of the harmless villagers. They asked me a thousand questions about my country, and in return for my information brought corn and milk for myself, and grass for my horse; kindled a fire in the hut where I was to sleep, and appeared very anxious to serve me."

Afterward, being robbed and stripped by banditti in the wilderness, he informs us that the robbers stood considering whether they should leave him quite destitute: even in their minds, humanity partially prevailed over avarice; they returned the worst of two shirts, and a pair of trowsers; and as they went away, one of them threw back his hat. At the next village, Mr Park entered a complaint to the Dooty, or chief man, who continued very calmly smoking while he listened to the narration: but when he had heard all the particulars, he took the pipe from his mouth, and tossing up the sleeve of his cloak with an indignant air, he said, "You shall have everything restored to you—I have sworn it." Then, turning to an attendant, he added, "Give the white man a draught of water; and with the first light of morning go over the hills, and inform the Dooty of Bammakoo, that a poor white man, the king of Bambarra's stranger, has been robbed by the king of Foolodoo's people." He then invited the traveller to remain with him, and share his provisions, until the messenger returned. Mr Park accepted the kind offer most gratefully: and in a few days his horse and clothes were restored to him.

At the village of Nemacoo, where corn was so scarce that the people were actually in a state of starvation, a negro pitied his distress and brought him food.

At Kamalia, Mr Park was earnestly dissuaded by an African named Karfa, from attempting to cross the Jalonka wilderness during the rainy reason; to which he replied that there was no alternative—for he was so poor, that he must either beg his subsistence from place to place, or perish with hunger. Karfa eagerly inquired if he could eat the food of the country, adding that, if he would stay with him, he should have plenty of victuals, and a hut to sleep in; and that after he had been safely conducted to the Gambia, he might make what return he thought proper. He was accordingly provided with a mat to sleep on, an earthen jar for holding water, a small calabash for a drinking cup, and two meals a day, with a supply of wood and water, from Karfa's own dwelling. Here he recovered from a fever, which had tormented him several weeks. His benevolent landlord came daily to inquire after his health, and see that he had everything for his comfort. Mr Park assures us that the simple and affectionate manner of those around him contributed not a little to his recovery. He adds, "Thus was I delivered, by the friendly care of this benevolent negro, from a situation truly deplorable. Distress and famine pressed hard upon me; I had before me the gloomy wilderness of Jallonkadoo, where the traveller sees no habitation for five successive days. I had observed, at a distance, the rapid course of the river Kokaro, and had almost marked out the place where I thought I was doomed to perish, when this friendly negro stretched out his hospitable hand for my relief." Mr Park having travelled in company with a coffle of thirtyfive slaves, thus describes his feelings as they came near the coast: "Although I was now approaching the end of my tedious and toilsome journey, and expected in another day to meet with countrymen and friends, I could not part with my unfortunate fellow travellers,—doomed as I knew most of them to be, to a life of slavery in a foreign land,—without great emotion. During a peregrination of more than five hundred miles, exposed to the burning rays of a tropical sun, these poor slaves, amidst their own infinitely greater sufferings, would commiserate mine, and frequently, of their own accord, bring water to quench my thirst, and at night collect branches and leaves to prepare me a bed in the wilderness. We parted with mutual regret and blessings.—My good wishes and prayers were all I could bestow upon them, and it afforded me some consolation to be told that they were sensible I had no more to give."

The same enlightened traveller remarks, "All the negro nations that fell under my observation, though divided into a number of petty, independent states, subsist chiefly by the same means, live nearly in the same temperature, and possess a wonderful similarity of disposition. The Mandingoes, in particular, are a very gentle race, cheerful, inquisitive, credulous, simple, and fond of flattery. Perhaps the most prominent defect in their character, was that insurmountable propensity, which the reader must have observed to prevail in all classes, to steal from me the few effects I was possessed of. No complete justification can be offered for this conduct, because theft is a crime in their own estimation; and it must be observed that they are not habitually and generally guilty of it towards each other. But before we pronounce them a more depraved people than any other, it were well to consider, whether the lower class of people in any part of Europe, would have acted, under similar circumstances, with greater honesty towards a stranger. It must be remembered that the laws of the country afforded me no protection; that every one was permitted to rob me with impunity; and that some part of my effects were of as great value in the estimation of the negroes, as pearls and diamonds would have been in the eyes of a European. Let us suppose a black merchant of Hindostan had found his way into England, with a box of jewels at his back, and the laws of the kingdom afforded him no security—in such a case, the wonder would be not that the stranger was robbed of any part of his riches, but that any part was left for a second depredator.[1] Such, on sober reflection, is the judgment I have formed concerning the pilfering disposition of the Mandingo negroes toward me.

"On the other hand, it is impossible for me to forget the disinterested charity, and tender solicitude, with which many of these poor heathens, from the sovereign of Sego, to the poor women, who at different times received me into their cottages, sympathized with my sufferings, relieved my distress, and contributed to my safety. Perhaps this acknowledgment is more particularly due to the female part of the nation. Among the men, as the reader must have seen, my reception, though generally kind, was sometimes otherwise. It varied according to the tempers of those to whom I made application. Avarice in some, and bigotry in others, had closed up the avenues to compassion; but I do not recollect a single instance of hard-heartedness towards me in the women. In all my wanderings and wretchedness, I found them uniformly kind and compassionate; and I can truly say, as Mr Ledyard has eloquently said before me—'To a woman, I never addressed myself in the language of decency and friendship, without receiving a decent and friendly answer. If I was hungry, or thirsty, wet, or ill, they did not hesitate, like the men, to perform a generous action. In so free and so kind a manner, did they contribute to my relief, that if I were dry, I drank the sweeter draught; and if I were hungry, I ate the coarsest meal with a double relish.'

"It is surely reasonable to suppose that the soft and amiable sympathy of nature, thus spontaneously manifested to me in my distress, is displayed by these poor people as occasion requires, much more strongly toward those of their own nation and neighborhood. Maternal affection, neither suppressed by the restraints, nor diverted by the solicitudes of civilized life, is everywhere conspicuous among them, and creates reciprocal tenderness in the child. 'Strike me,' said a negro to his master, who spoke disrespectfully of his parent, 'but do not curse my mother.' The same sentiment I found to prevail universally."

"I perceived, with great satisfaction, that the maternal solicitude extended not only to growth and security of the person, but also, in a certain degree, to the improvement of the character; for one of the first lessons, which the Mandingo women teach their children is the practice of truth. A poor unhappy mother, whose son had been murdered by Moorish banditti, found consolation in her deepest distress from the reflection that her boy, in the whole course of his blameless life, had never told a lie."

Adanson, who visited Senegal, in 1754, describes the negroes as sociable, obliging, humane, and hospitable. "Their amiable simplicity," says he, "in this enchanting country, recalled to me the idea of the primitive race of man; I thought I saw the world in its infancy. They are distinguished by tenderness for their parents, and great respect for the aged." Robin speaks of a slave at Martinico, who having gained money sufficient for his own ransom, preferred to purchase his mother's freedom.

Proyart, in his history of Loango, acknowledges that the negroes on the coast, who associate with Europeans, are inclined to licentiousness and fraud; but he says those of the interior are humane, obliging, and hospitable. Golberry repeats the same praise, and rebukes the presumption of white men in despising "nations improperly called savage, among whom we find men of integrity, models of filial, conjugal, and paternal affection, who know all the energies and refinements of virtue; among whom sentimental impressions are more deep, because they observe, more than we, the dictates of nature, and know how to sacrifice personal interest to the ties of friendship."

Joseph Rachel, a free negro of Barbadoes, having become rich by commerce, consecrated all his fortune to acts of charity and beneficence. The unfortunate of all colors, shared his kindness. He gave to the needy, lent without hope of return, visited prisoners, and endeavored to reform the guilty. He died in 1758. The philanthropists of England speak of him with the utmost respect.

Jasmin Thoumazeau was born in Africa, 1714, and sold at St Domingo, 1736. Having obtained his freedom, he returned to his native country, and married a negro girl of the Gold Coast. In 1756, he established a hospital for poor negroes and mulattoes. During more than forty years, he and his wife devoted their time and fortune to the comfort of such invalids as sought their protection. The Philadelphian Society, at the Cape, and the Agricultural Society of Paris, decreed medals to this worthy and benevolent man.

Louis Desrouleaux was the slave of M. Pinsum, a captain in the negro trade, who resided at St Domingo. The master having amassed great riches, went to reside in France, where circumstances combined to ruin him. Depressed in fortune and spirits, he returned to St Domingo; but those who had formerly been proud of his friendship, now avoided him. Louis heard of his misfortunes and immediately went to see him. The scales were now turned; the negro was rich, and the white man poor. The generous fellow offered every assistance, but advised M. Pinsum by all means to return to France, where he would not be pained by the sight of ungrateful men. "But I cannot gain a living there," replied the white man. "Will the annual revenue of fifteen thousand francs be sufficient?" asked Louis. The Frenchman's eyes filled with tears. The negro signed the contract, and the pension was regularly paid, till the death of Louis Desrouleaux, in 1774.

Benoit of Palermo, also named Benoit of Santo Fratello, sometimes called The Holy Blade, was a negro, and the son of a female slave. Roccho Pirro, author of the Sicilia Sacra, eulogizes him thus: "Nigro quidem corpore sed candore animi prœclarisimus quern miraculis Deus contestatum esse voluit." "His body was black, but it pleased God to testify by miracles the whiteness of his soul." He died at Palermo, in 1589, where his tomb and memory are much revered. A few years ago, it was said the Pope was about to authorize his canonization. Whether he is yet registered as a saint in the Calendar, I know not; but many writers agree that he was a saint indeed—eminent for his virtues, which he practised in meekness and silence, desiring no witness but his God.

The moral character of Toussaint L'Ouverture is even more worthy of admiration than his intellectual acuteness. What can be more beautiful than his unchanging gratitude to his benefactor, his warm attachment to his family, his high-minded sacrifice of personal feeling to the public good! He was a hero in the sublimest sense of the word. Yet he had no white blood in his veins—he was all negro.

The following description of a slave-market at Brazil is from the pen of Doctor Walsh: "The men were generally less interesting objects than the women; their countenances and hues were very varied, according to the part of the African coast from which they came; some were soot black, having a certain ferocity of aspect that indicated strong and fierce passions, like men who were darkly brooding over some deep-felt wrongs, and meditating revenge. When any one was ordered, he came forward with a sullen indifference, threw his arms over his head, stamped with his feet, shouted to show the soundness of his lungs, ran up and down the room, and was treated exactly like a horse put through his paces at a repository; and when done, he was whipped to his stall.

"Many of them were lying stretched on the bare boards; and among the rest, mothers with young children at their breasts, of which they seemed passionately fond. They were all doomed to remain on the spot, like sheep in a pen, till they were sold; they have no apartment to retire to, no bed to repose on, no covering to protect them; they sit naked all day, and lie naked all night, on the bare boards, or benches, where we saw them exhibited.

"Among the objects that attracted my attention in this place were some young boys, who seemed to have formed a society together. I observed several times in passing by, that the same little group was collected near a barred window; they seemed very fond of each other, and their kindly feelings were never interrupted by peevishness; indeed, the temperament of a negro child is generally so sound, that he is not affected by those little morbid sensations, which are the frequent cause of crossness and ill-temper in our children. I do not remember, that I ever saw a young black fretful, or out of humor; certainly never displaying those ferocious fits of petty passion, in which the superior nature of infant whites indulges. I sometimes brought cakes and fruit in my pocket, and handed them in to the group. It was quite delightful to observe the generous and disinterested manner in which they distributed them. There was no scrambling with one another; no selfish reservation to themselves. The child to whom I happened to give them, took them so gently, looked so thankfully, and distributed them so generously, that I could not help thinking that God had compensated their dusky hue, by a more than usual human portion of amiable qualities."

Several negroes in Jamaica were to be hung. One of them was offered his life, if he would hang the others; he preferred death. A negro slave who was ordered to do it, asked time to prepare; he went into his cabin, chopped off his right hand with an axe, and then came back, saying he was ready.

Sutcliff in his Travels, speaks of meeting a coffle of slaves in Maryland, one of whom had voluntarily gone into slavery, in hopes of meeting her husband, who was a free black and had been stolen by kidnappers. The poor creature was in treacherous hands, and it is a great chance whether she ever saw her husband again.

An affecting instance of negro friendship may be found in 1 Bay's Report, 260-3. A female slave in South Carolina was allowed to work out in the town, on condition that she paid her master a certain sum of money, per month. Being strong and industrious, her wages amounted to more than had been demanded in their agreement. After a time she earned enough to buy her freedom; but she preferred to devote the sum to the emancipation of a negro girl, named Sally, for whom she had conceived a strong affection. For a long time the master pretended to have no property in his slave's manumitted friend, never paid taxes for her, and often spoke of her as a free negro. But, from some motive or other, he afterward claimed Sally as his slave, on the ground that no slave could make any purchase on his own account, or possess anything which did not legally belong to his master. It is an honor to Chief Justice Rutledge that his charge was given in a spirit better than the laws. He concluded by saying, "If the wench chose to appropriate the savings of her extra labor to the purchase of this girl, in order to set her free, will a jury of the country say, No? I trust not. I hope they are too upright and humane, to do such manifest violence to such an extraordinary act of benevolence." By the prompt decision of the jury, Sally was declared free.[2]

In speaking of the character of negroes, it ought not to be omitted that many of them were brave and faithful soldiers during our Revolution. Some are now receiving pensions for their services. At New Orleans, likewise, the conduct of the colored troops was deserving of the highest praise.

It is common to speak of the negroes as a very unfeeling race; and no doubt the charge has considerable truth when applied to those in a state of bondage: for slavery blunts the feelings, as well as stupifies the intellect. The poor negro is considered as having no right in his wife and children. They may be suddenly torn from him to be sold in a distant market; but he cannot prevent the wrong. He may see them exposed to every species of insult and indignity; but the law, which stretches forth her broad shield to guard the white man's rights, excludes the negro from her protection. They may be tied to the whipping post and die under moderate punishment; but he dares not complain. If he murmur, there is the tormenting lash; if he resist, it is death.—And the injustice extends even beyond the grave; for the story of the slave is told by his oppressor, and the manly spirit which the poor creature shows, when stung to the very heart's core, is represented as diabolical revenge. A short time ago, I read in a Georgia paper, what was called a horrid transaction, on the part of the negro. A slave stood by and saw his wife whipped, as long as he could possibly endure the sight; he then called out to the overseer, who was applying the lash, that he would kill him if he did not use more mercy. This probably made matters worse; at all events the lashing continued. The husband, goaded to frenzy, rushed upon the overseer, and stabbed him three times. White men! what would you do, if the laws admitted that your wives might "die" of "moderate punishment," administered by your employers? The overseer died, and his murderer was either burned or shot,—I forget which. The Georgia editor viewed the subject only on one side—viz.—the monstrous outrage against the white man—the negro's wrongs passed for nothing! It was very gravely added to the account (probably to increase the odiousness of the slave's offence,) that the overseer belonged to the Presbyterian church! I smiled,-because it made me think of a man, whom I once heard described as "a most excellent Christian, that would steal timber to build a church."

This instance shows that even slaves are not quite destitute of feeling—yet we could not wonder at it, if they were. Who could expect the kindly affections to expand in such an atmosphere! Where there is no hope, the heart becomes paralyzed: it is a merciful arrangement of Divine Providence, by which the acuteness of sensibility is lessened when it becomes merely a source of suffering.

But there are exceptions to this general rule; instances of very strong and deep affection are sometimes found in a state of hopeless bondage. Godwin, in his eloquent Lectures on Colonial Slavery, quotes the following anecdote, as related by Mr T. Pennock, at a public meeting in England:

"A few years ago it was enacted, that it should not be legal to transport once established slaves from one island to another; and a gentleman owner, finding it advisable to do so before the act came in force, the removal of a great part of his live stock was the consequence. He had a female slave, a Methodist, and highly valuable to him (not the less so for being the mother of eight or nine children), whose husband, also of our connexion, was the property of another resident on the island, where I happened to be at the time. Their masters not agreeing on a sale, separation ensued, and I went to the beach to be an eye witness of their behaviour in the greatest pang of all. One by one, the man kissed his children, with the firmness of a hero, and blessing them, gave as his last words—(oh! will it be believed, and have no influence upon our veneration for the negro?) 'Farewell! Be honest, and obedient to your master!" At length he had to take leave of his wife: there he stood (I have him in my mind's eye at this moment), five or six yards from the mother of his children, unable to move, speak, or do anything but gaze, and still to gaze, on the object of his long affection, soon to cross the blue waves forever from his aching sight. The fire of his eyes alone gave indication of the passion within, until after some minutes standing thus, he fell senseless on the sand, as if suddenly struck down by the hand of the Almighty. Nature could do no more; the blood gushed from his nostrils and mouth, as if rushing from the terrors of the conflict within; and amid the confusion occasioned by the circumstance, the vessel bore off his family forever from the island! After some days he recovered, and came to ask advice of me. What could an Englishman do in such a case? I felt the blood boiling within me; but I conquered. I browbeat my own manhood, and gave him the humblest advice I could."

The following account is given by Mr Gilgrass, one of the Methodist missionaries at Jamaica: "A master of slaves, who lived near us in Kingston, exercised his barbarities on a Sabbath morning while we were worshiping God in the Chapel; and the cries of the female sufferers have frequently interrupted us in our devotions. But there was no redress for them, or for us. This man wanted money; and one of the female slaves having two fine children, he sold one of them, and the child was torn from her maternal affection. In the agony of her feelings, she made a hideous howling; and for that crime she was flogged. Soon after he sold her other child. This 'turned her heart within her,' and impelled her into a kind of madness. She howled night and day in the yard; tore her hair; ran up and down the streets and the parade, rending the heavens with her cries, and literally watering the earth with her tears. Her constant cry was, 'Da wicked massa, he sell me children.—Will no buckra master pity nega? What me do! Me have no child! As she stood before my window, she said, lifting her hands towards heaven, 'Do, me master minister, pity me! Me heart do so, (shaking herself violently,) me heart do so, because me have no child. Me go a massa house, in massa yard, and in me hut, and me no see em;' and then her cry went up to God. I durst not be seen looking at her."

A similar instance of strong affection happened in the city of Washington, December, 1815. A negro woman, with her two children, was sold, near Bladensburgh, to Georgia traders; but the master refused to sell her husband. When the coffle reached Washington, on their way to Georgia, the poor creature attempted to escape, by jumping from the garret window of a three-story brick tavern. Her arms and back were dreadfully broken. When asked why she had done such a desperate act, she replied, "They brought me away, and would n't let me see my husband; and I didn't want to go. I was so distracted that I did not know what I was about: but I did n't want to go—and I jumped out of the window." The unfortunate woman was given to the landlord as a compensation for having her taken care of at his house; her children were sold in Carolina; and thus was this poor forlorn being left alone in her misery. In all this wide land of benevolence and freedom, there was no one who could protect her: for in such cases, the laws come in, with iron grasp, to check the stirrings of human sympathy.

Another complaint is that slaves have most inveterate habits of laziness. No doubt this is true—it would be strange indeed if it were otherwise. Where is the human being, who will work from a disinterested love of toil, when his labor brings no improvement to himself, no increase of comfort to his wife and children?Pelletan, in his Memoirs of the French Colony of Senegal, says, "The negroes work with ardor, because they are now unmolested in their possessions and enjoyments. Since the suppression of slavery, the Moors make no more inroads upon them, and their villages are rebuilt and re-peopled." Bosman, who was by no means very friendly to colored people, says: "The negroes of Cabomonte and Juido, are indefatigable cultivators, economical of their soil, they scarcely leave a foot-path to form a communication between the different possessions; they reap one day, and the next they sow the same earth, without allowing it time for repose."

It is needless to multiply quotations; for the concurrent testimony of all travellers proves that industry is a common virtue in the interior of Africa.

Again, it is said that the negroes are treacherous, cunning, dishonest, and profligate. Let me ask you, candid reader, what you would be, if you labored under the same unnatural circumstances? The daily earnings of the slave, nay, his very wife and children, are constantly wrested from him, under the sanction of the laws; is this the way to teach a scrupulous regard to the property of others? How can purity be expected from him, who sees almost universal licentiousness prevail among those whom he is taught to regard as his superiors? Besides, we must remember how entirely unprotected the negro is in his domestic relations, and how very frequently husband and wife are separated by the caprice, or avarice, of the white man. I have no doubt that slaves are artful; for they must be so. Cunning is always the resort of the weak against the strong; children, who have violent and unreasonable parents, become deceitful in self-defence.

The only way to make young people sincere and frank, is to treat them with mildness and perfect justice. The negro often pretends to be ill in order to avoid labor; and if you were situated as he is, you would do the same. But it is said that the blacks are malignant and revengeful. Granting it to be true,—is it their faulty or is it owing to the cruel circumstances in which they are placed? Surely there are proofs enough that they are naturally a kind and gentle people. True, they do sometimes murder their masters and overseers; but where there is utter hopelessness, can we wonder at occasional desperation? I do not believe that any class of people subject to the same influences, would commit fewer crimes. Dickson, in his letters on slavery, informs us that among one hundred and twenty thousand negroes and creoles of Barbadoes, only three murders have been known to be committed by them in the course of thirty years; although often provoked by the cruelty of the planters."

In estimating the vices of slaves, there are several items to be taken into the account. In the first place, we hear a great deal of the negroes' crimes, while we hear very little of their provocations. If they murder their masters, newspapers and almanacs blazon it all over the country; but if their masters murder them, a trifling fine is paid, and nobody thinks of mentioning the matter. I believe there are twenty negroes killed by white men, where there is one white man killed by a black. If you believe this to be mere conjecture, I pray you examine the Judicial Reports of the Southern States. The voice of humanity, concerning this subject, is weak and stifled; and when a master kills his own slave we are not likely to hear the tidings—but the voice of avarice is loud and strong; and it sometimes happens that negroes "die" "under a moderate punishment" administered by other hands: then prosecutions ensue, in order to recover the price of the slave; and in this way we are enabled to form a tolerable conjecture concerning the frequency of such crimes.

I have said that we seldom hear of the grievous wrongs which provoke the vengeance of the slave; I will tell an anecdote, which I know to be true, as a proof in point. Within the last two years, a gentleman residing in Boston, was summoned to the West Indies in consequence of troubles on his plantation. His overseer had been killed by the slaves. This fact was soon made public; and more than one exclaimed, "what diabolical passions these negroes have!" To which I replied that I only wondered they were half as good as they were. It was not long, however, before I discovered the particulars of the case; and I took some pains that the public should likewise be informed of them. The overseer was a bad, licentious man. How long and how much the slaves endured under his power I know not, but at last, he took a fancy to two of the negroes' wives, ordered them to be brought to his house, and in spite of their entreaties and resistance, compelled them to remain as long as he thought proper. The husbands found their little huts deserted, and knew very well where the blame rested. In such a case, you would have gone to law; but the law does not recognise a negro's rights—he is the property of his master, and subject to the will of his agent. If a slave should talk of being protected in his domestic relations, it would cause great merriment in a slave-holding State; the proposition would be deemed equally inconvenient and absurd. Under such circumstances, the negro husbands took justice into their own hands. They murdered the overseer. Four innocent slaves were taken up, and upon every slight circumstantial evidence were condemned to be shot; but the real actors in this scene passed unsuspected. When the unhappy men found their companions were condemned to die, they avowed the fact, and exculpated all others from any share in the deed. Was not this true magnanimity? Can you help respecting those negroes? If you can, I pity you.

Since the condition of slaves is such as I have described, are you surprised at occasional insurrections? You may regret it most deeply; but can you wonder at it. The famous Captain Smith, when he was a slave in Tartary, killed his overseer and made his escape. I never heard him blamed for it—it seems to be universally considered a simple act of self-defence. The same thing has often occurred with regard to white men taken by the Algerines.

The Poles have shed Russian "blood enough to float our navy;" and we admire and praise them, because they did it in resistance of oppression. Yet they have suffered less than black slaves, all the world over, are suffering. We honor our forefathers because they rebelled against certain principles dangerous to political freedom; yet from actual, personal tyranny, they suffered nothing: the negro, on the contrary, is suffering all that oppression can make human nature suffer. Why do we execrate in one set of men, what we laud so highly in another? I shall be reminded that insurrections and murders are totally at variance with the precepts of our religion; and this is most true. But according to this rule, the Americans, Poles, Parisians, Belgians, and all who have shed blood for the sake of liberty, are more to blame than the negroes; for the former are more enlightened, and can always have access to the fountain of religion; while the latter are kept in a state of brutal ignorance—not allowed to read their Bibles—knowing nothing of Christianity, except the examples of their masters, who profess to be governed by its maxims.

I hope I shall not be misunderstood on this point. I am not vindicating insurrections and murders; the very thought makes my blood run cold. I believe revenge is always wicked; but I say, what the laws of every country acknowledge, that great provocations are a palliation of great crimes. When a man steals food because he is starving, we are more disposed to pity, than to blame him. And what can human nature do, subject to continual and oppressive wrong—hopeless of change—not only unprotected by law, but the law itself changed into an enemy—and to complete the whole, shut out from the instructions and consolations of the Gospel! No wonder the West Indian missionaries found it very difficult to decide what they ought to say to the poor, suffering negroes! They could indeed tell them it was very impolitic to be rash and violent, because it could not, under existing circumstances, make their situation better, and would be very likely to make it worse; but if they urged the maxims of religion, the slaves might ask the embarrassing question, is not our treatment in direct opposition to the precepts of the gospel? Our masters can read the Bible—they have a chance to know better. Why do not Christians deal justly by us, before they require us to deal mercifully with them?

Think of all these things, kind-hearted reader. Try to judge the negro by the same rules you judge other men; and while you condemn his faults, do not forget his manifold provocations.

- ↑ Or suppose a colored pedler with valuable goods travelling in slave states, where the laws afford little or no protection to negro property, what would probably be his fate?

- ↑ Stroud says of the above, "This is an isolated case, of pretty early date; it deserves to be noticed because it is in opposition to the spirit of the laws, and to later decisions of the courts."