Archaeological Journal/Volume 1/Iconography and Iconoclasm

ICONOGRAPHY AND ICONOCLASM.

Iconography, carried to excess, and addressed to the imaginations of an ignorant, an idle, and a vicious populace, naturally leads to idolatry. Hence it was that the inspired law-giver of the Israelites, who was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians, that is, was intimately acquainted with the whole system of the Egyptian philosophy and mythology, and had witnessed the pernicious effects of this system on the moral and religious conduct of the Egyptian population, was instructed to guard the Israelites most rigorously, when they came up out of Egypt into the promised land of Canaan, against the sin of idolatry; as the natural consequence of the perversion, the abuse, and the excess of that which in itself, perhaps, and in its origin, might be thought innocent. "Thou shalt not make to thyself any graven image, nor the likeness of any thing," &c., is the second commandment of the first table, and therefore cannot be resisted or evaded. But the Iconoclasts are led by their zeal and enthusiasm to overlook the qualifying and important member of the sentence,—"to thyself." Painting, statuary, sculpture,— all the imitative arts,—nay, the very cultivation of the soil, the reproduction of the animal form, and the advances of science, would be retarded, or even annihilated, as far as it depends upon us, were we to attempt to carry into effect, in its utmost latitude, the rigid and literal interpretation of this commandment, which the Iconoclast, without any reserve, limitation, or qualification, would persuade us to adopt. But what is the very substance of the injunction? Thou shalt not make these similitudes,—these works of thine own hands,—"to thyself"—from any selfish motive, for any selfish use or gratification. Much less shalt thou bow down to them and worship them according to thine own will and pleasure. Whenever this was done, the idols, the objects of this perverted taste, were destroyed on the common maxim, that when the cause is removed the effect will cease. And, however much we may regret the loss of many splendid works of art, which might gratify and instruct every generation of mankind, yet we may console ourselves with the reflection that enough remains to illustrate almost every page of history, if we be careful and industrious enough to examine and study them. Much has been lately accomplished in this way; and we are particularly indebted to the learned author of the "Christian Iconography," of whose work some account was given in the first number of the Archæological Journal.

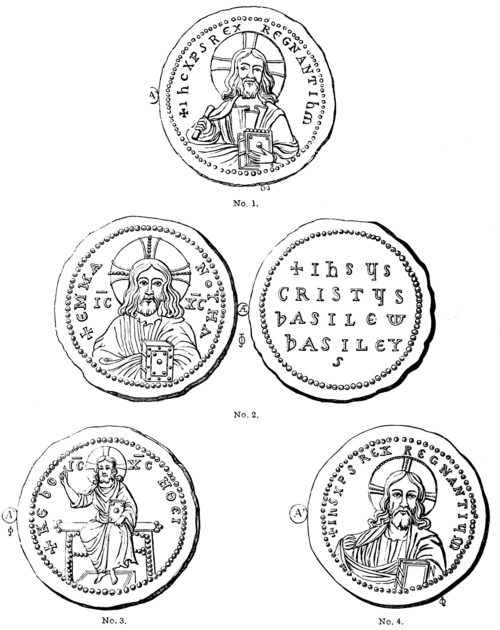

In illustration of the same subject the following specimens of Christian Iconography from coins are here submitted to the consideration of the readers of this Journal:—

No. 1. A gold coin of Basilius I. and his father Constantinus, c. A.D. 867.

No. 2. A copper coin of Johannes Zimisces, c. A.D. 969.

No. 3. A gold coin of Alexius Comnenus, c. A.D. 1080.

No. 4. A gold coin of Constantinus VII. and his associate in the empire, Romanus Locapenus, c. A.D. 912.

Of all the coins here engraved that of Zimisces is the finest and most interesting. This is of copper; and the superiority of that metal for decision of outline is well known to Numismatists. There is also a peculiarity of character, which distinguishes this coin from the rest. The head of Christ is on the obverse, instead of the head of the reigning emperor. Hence the Byzantine coins, not otherwise distinguished, are easily appropriated to Zimisces. Perhaps some reasons of state prevented this politic prince, though his coronation was publicly solemnized, and his reign was popular, from assuming all the external signs of his imperial office. Under his usurpation or regency of twelve years, according to Gibbon, though Zonaras and most other authors say six, Basil and Constantine had silently grown to manhood. On the 10th of January, 975-6, these youthful brothers ascended the throne of Constantinople. Their reign is designated, by the historian of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, as the longest and most obscure of the Byzantine history. Yet it was during this eventful period, here so carelessly and contemptuously despatched, that those great struggles were made both in Europe and Asia, which laid the foundation of the modern dynasties both of the east and west. In subsequent chapters of the work some compensation is made for this hasty and abrupt dismissal of the subject. The entire reign of these two brothers combined together exceeded fifty-three years, of which Basil occupied fifty, dying suddenly at the age of seventy. This was the second of that name. The first Basil, who is represented on the obverse of his coins in company with his son, a youth who died at the age of thirteen, holding an elevated cross between them, is the first emperor who placed the figure of the Saviour, with His titles and attributes, on his coins, if we may trust to the series engraved in the Thesaurus Palatinus of Beger; who candidly admits, nevertheless, that Justinian the Second, called Rhinotmetus, was by some supposed to be the first; probably because his own mutilated face was unworthy of being perpetuated. The custom certainly prevailed through several reigns. There are eleven examples engraved in Beger's work; from which four have been here selected, as containing something peculiar. They all have the radiated nimbus, bounded by a circular outline, with flowing hair, generally parted over the forehead, and a slight portion of beard, except in the coin of Manuel, who came to the throne in 1143. This is the last of the series given by Beger, who concludes his work with a short review of the Roman empire from its commencement to its fall. In none of these examples of imperial Iconography does he discover any traces of idolatry, or any license and authority for that adoration of images, the controversy about which occasioned so much animosity and Iconoclasm in the eastern and western world for so many centuries. The usual monograms and titles of Jesus, of Christ, of Emmanuel, the King of kings, with KƐ BO—KYPIƐ Βοηθει, &c., only serve to remind both sovereigns and subjects of their dependence on Divine Providence for the continuance of their prosperity, or their deliverance from adversity. But the invocation of the "Mother of God," which soon followed, is a departure from this simplicity.

The transition to Mariolatry may, perhaps, be a curious and interesting subject for investigation. The word ΘΕΟΤΟΚΟΣ is ambiguous. It may signify the "Mother of God," or it may be synonymous with Diogenes, that is, "of Divine origin." Accordingly, we find the first invocation of the Virgin Mother by this name on a coin of Romanus Diogenes, who came to the imperial throne of Constantinople in the year 1068. He is represented as crowned by the Virgin Mary; and the legends of this and some subsequent coins exhibit those revolting invocations for help from the Mother of God which have been so frequently condemned as derogatory from the supreme Majesty of heaven. For about four or five centuries, therefore, "Jesus have mercy, Mary help," were invocations too commonly united. In another coin there is the figure of St. George assisting the emperor, Calo-Johannes, in holding a patriarchal cross, with the figure of the Saviour, sitting on a chair, on the reverse. The nimbus, surrounding the heads both of the Virgin and St. George, is quite plain. From the coins of Alexius Comnenus, as well as others of the Comnenian family, we may infer, that they acknowledged Christ as their only helper and defender. j. i.