Archaeological Journal/Volume 11/The Additions to the Collections of National Antiquities in the British Museum

ON THE ADDITIONS TO THE COLLECTION OF NATIONAL ANTIQUITIES IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

The accessions to the British collection during the past year have been very numerous, and they include many objects of more than ordinary interest. It is gratifying to be able to state that this department of the Museum has received presents from thirty-three donors, and that the number of additions by gift and purchase exceeds 1270, being more than double that in the previous year.

Two acquisitions demand special notice, both comprising antiquities of various periods. The first is the interesting collection of antiquities presented by Mr. Henry Drummond, M.P.; consisting of British, Roman, and Saxon remains found on Farley Heath,[1] in Surrey, among which are some British and Roman coins of great rarity and value. The other is the collection formed by the late Dr. Mantell, chiefly from Sussex, which was obtained by purchase. I shall notice the more remarkable objects contained in these two groups under the class to which they respectively belong.

Among the additions made to Primeval and Celtic antiquities, the following must be mentioned: an urn from a tumulus in Delamere Forest, Cheshire, presented by Sir Philip Egerton; which was discovered under circumstances stated in a previous volume of this Journal;[2] three urns found in a tumulus at Alfriston in Sussex;[3] several stone celts and British urns found in the same county, from the Mantell Collection,[4] including the curious ornamented clay ball described in a previous volume,[5] and an urn found at Felixstow in Suffolk.

To these may be added several objects found in Ireland; especially two highly finished flint knives, a beautifully formed stone hammer head, two urns, and a ball formed of hornblende schist, exhibiting six circular faces with hollows between; which greatly resembles a ball engraved in Wilson's Prehistoric Annals of Scotland, (p. 139).

The Museum has also acquired several bronze celts as well as specimens of the metal found with such implements, viz. one from Welwyn in Hertfordshire, presented by Mr. W. Blake;[6] several found at Chrishall or Elmdon in Essex;[7] a few from Farley Heath, Surrey; and a lump of metal found with celts at Westwick Row in Hertfordshire, presented by Mr. John Evans. In all these cases, the celts appear to be either unfinished or imperfectly cast, as if they were found on the spot where they had been manufactured. The same was the case in the discoveries of bronze implements[8] at Carlton Rode, Norfolk; Westow, Yorkshire; Romford, Essex;West Halton, Lincolnshire; and in the Isle of Alderney. Most of the latter were found accompanied by lumps of metal which had been assumed to be the residuum of the melting-pot. On examining, however, the specimens acquired by the Museum and enumerated above, the metal will be seen to be pure copper; and it suggests that the makers of the celts, which are bronze, must have themselves mixed in the tin as required, contrary to what is mentioned of the Britons by Cæsar; "Ære utuntur importato."[9] It would be well to examine all metallic substances found with such remains, as the lumps of tin would perhaps be discovered in company with the copper.

We are indebted to the Hon. W. Owen Stanley for some interesting bronze objects found in the Island of Anglesey: they are very similar to Irish gold ornaments in their form, and were found on a spot known as the "Irishmen's huts.[10]" I should also mention some gold ornaments consisting of a cupped ring, string of beads, and three counterfeit cleft-rings of ancient date, all found in Ireland, as well as several celts of rare form.[11]

A very interesting addition was made to later Celtic antiquities by the kindness of Mr. Thomas Gray of Liverpool. It is the well-known beaded torc and bronze bowl found in Lochar Moss, Dumfriesshire.[12] A bronze buckle of the same period has been acquired, which was found on the South Downs[13]: it retains traces of enamel, and is very similar to some of the objects found at Polden Hill and Stanwick.

Of Celtic art of a still more recent date some interesting specimens have been added from Ireland. They consist of brooches of bronze and iron, buckles, fragments of croziers and ornaments, which, though contemporaneous with the Saxon remains in England, are quite distinct from them in the style of their ornamentation and workmanship.

The additions to the Roman portion of the collection have been, as usual, numerous. The most important of them is the sarcophagus discovered in Haydon Square, Minories, and presented to the Museum by the incumbent and church- wardens of the parish, together with the lid of the leaden coffin found within it. Ample notices of this interesting discovery have appeared in the Archæological Journal, x., 255; Smith's Collectanea Antiqua, vol. iii., p. 46; and Journal of the British Archæological Association, vol. ix. A sepulchral inscription found at Lincoln has been presented by Mr. Arthur Trollope. It is represented on the next page. It records Julius Valerius Pudens, son of Julius, of the Claudian tribe and a native of Savia; he appears to have been a soldier of the second legion and of the century of Dossennus Proculus, and to have lived thirty years, two of them as a pensioner.[14]

Some interesting sepulchral antiquities were presented by Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Shiffner, discovered in and around a stone sarcophagus found at Westergate, near Chichester. They consist of pottery, fragments of a mirror, a glass bottle, and two enamelled fibulæ. A group of the pottery is represented in the accompanying engraving. The ware is of a pale colour, and has suffered considerably from the damp of the earth in which it has lain. The mirror appears to have been square. The vases as well as the sarcophagus exhibit great similarity to the sepulchral deposit which was found at Sepulchral Inscription found at Lincoln.

Presented to the British Museum by Arthur Trollope, Esq.

Height, 5 feet.

The collection presented by Mr. Drummond is very rich in enamelled ornaments, including brooches, studs, handles, and other things so enriched. The most remarkable are the two stands resting on four legs, which are here represented. They are enamelled red, blue, and green, and appear to have been intended to support the delicate amphora-shaped glass vases which are occasionally found, and are supposed to have contained precious unguents. Some fragments of bronze ornaments, from near Devizes, partly enamelled, were given to the Museum by the Rev. E. Wilton.[15]

A considerable number of potter's marks on so-called "Samian" ware were purchased at the sale of the late Mr. Price's collection. Several hand- bricks have been presented by Mr. Arthur Trollope, found in Lincolnshire, and bearing unmistakeable evidence of their having been employed to support pottery while baking.[16] We are indebted to Mr. Beale for a clay cylinder, evidently intended for the same purpose, found with other Roman remains at Oundle, in Northamptonshire.

Among other remains of this period it will be sufficient to mention an iron dagger in a bronze sheath,[17] found in the Thames; a bronze figure of Cupid from Haynford,[18] in Norfolk; a very beautiful glass vessel found at Colchester,[19] from the Mantell Collection; various Roman vessels of earthenware found on the borders of Hertfordshire, in Suffolk, and at Colchester, and several white-metal vessels found at Icklingham in Suffolk.

With regard to Saxon antiquities, a branch of British archæology in which the Museum is especially deficient, a very welcome accession is to be found in those presented by Viscount Folkestone. They are the result of the excavations conducted by Mr. Akerman on Harnham Hill, near Salisbury, and are especially valuable on account of the careful and scientific manner in which that gentleman conducted his researches. A detailed account of them will shortly appear in the Archæologia. We are indebted to Mr. Josiah Goodwyn for several iron weapons discovered at Harnham previously to Mr. Akerman's excavations. A few Kentish antiquities of this period were included in the Mantell Collection, as well as some interesting relics from Sussex. Among the latter should be noticed the gold ring found at Bormer,[20] of which a representation is annexed. Its similarity to the gold ornaments found at Soberton,[21] with coins of William the Conqueror, seems to preclude our attributing this object to an earlier period.

Two urns and bronze ornaments from Quarrington in Lincolnshire, have been presented by the Rev. E. Trollope; another urn, from Pensthorpe, in Norfolk, by Mr. Greville Chester; and a circular brooch from Fairford by Mr. J. O. Westwood.

The singular copper dish found at Chertsey has been aquired for the Museum. It is chiefly remarkable for an inscription on its rim, published in the Archæologia[22] by Mr. Kemble, who considers it to be a mixture of Saxon Runes and uncial letters. The interpretation of the inscription does not seem wholly satisfactory: it greatly resembles au archaic Sclavonic inscription, but it has not been decyphered by any of those conversant with the languages of that class.

The additions made to the Medieval Collection have been of considerable interest. Among those connected with England, either by the place of their discovery or by their workmanship, one of the most remarkable is the enamelled bowl found near Sudbury, Suffolk,[23] and presented to the Museum by the Hon. Mrs. Upcher, It appears to be the lower part of a ciborium or receptacle for the host, and greatly resembles one of these vessels preserved in the Museum of the Louvre at Paris.[24] The body of the bowl is ornamented with enamelled lozenges, separated by bands of gilt metal, enriched with pastes. In each lozenge is a half-length figure of an angel bearing a wafer or some sacred emblem. The figures are of metal and the details engraved in outline. The rim is enriched with a band, engraved in imitation of an Arabic inscription. The bowl is supported by a foot of pierced metal-work, representing four figures interlaced with stiff scrolls of foliage. It is not so elaborate as the specimen preserved in the Louvre, but the extraordinary similarity in the details of both would lead us to believe that they are not only the productions of the same locality, but of the same hand. The Paris ciborium furnishes us with evidence on both of these points, as it bears an inscription recording the name of its maker, Magister G. Alpais, and the place, Limoges. The date should seem to be the middle of the fourteenth century.

I should next mention a brass ewer 1314 inches in height, in the form of a knight on horseback, found in the river Tyne, near Hexham. It has been engraved in the "Archæologia Æliana," vol. iv. p. 76, and in "Antiquarian Gleanings in the North of England," pl. xxii.; in the former work will be found a most interesting paper by Dr. Charlton of Newcastle on these quaintly-formed ewers.

Three medallions, found in Bedfordshire, also claim our attention from their connection with an English Abbey, and the probability of their being of native workmanship. Two of them are 434 inches in diameter; on one is the Virgin and Child in high relief, under a canopy in gilt metal, the back ground of red enamel, charged with the arms of Wardon Abbey, az. 3 pears or,; on the other is a crucifix between St. Mary and St. John, who are standing on brackets springing from the foot of the cross: the ground of this is of blue enamel, and on it are two croziers and the letters W. C. Both these medallions have a pierced border of gilt metal composed of angels. The third medallion is 412 inches in diameter; in the centre is an angel in high relief, issuing from clouds, which are partly in relief and partly represented on the plate by blue and white enamel. He holds before his breast a silver shield, on which is a crozier between the letters W. C. The border is composed of Tudor flowers, four of which project beyond the others. The letters on these medallions probably indicate the name of the abbot under whose superintendence, or at whose expense, the shrine to which they may have belonged, was executed. The list of the Abbots of Wardon is too imperfect to enable us to identify this personage. The workmanship appears to belong to the latter half of the fifteenth century.

To a similar school of art and same period must be referred another recent acquisition; a processional cross said to have been found at Glastonbury Abbey. It is of gilt metal with a crucifix between St. Mary and St. John on brackets. Several crosses of a like character have been discovered in various parts of England and Ireland.

Another object to be noticed, is a very curious astrolabe presented to the Museum by Mr. Mayer, F.S.A., of Liverpool. It is of especial interest as it bears the inscription, Blakene me fecit anno domini, 1342. It is covered with Arabic numerals, and was evidently made for English latitudes. The collection of instruments for ascertaining time by the heavenly bodies has been further increased by three viatoria or pocket sun-dials; one found in the river Crane at Isleworth and presented by Mr. H. C. Pidgeon; another of German workmanship, presented by Mr. M. Rohde Hawkins; and a third made by C. Whitwell, which has been purchased.

Among other acquisitions, the following should be mentioned;—a gourd-shaped bottle[25] found at Newbury, in Berkshire; several enamelled badges, one of them presented by Mr. W. Chaffers; a figure in stone of St. George, found at Winchester, and presented by the Rev. W. H. Gunner[26]; a monumental brass of a civilian, date about 1480, presented by Mr. John Hewitt; a three-legged caldron with inscriptions obtained at Shudy Camps, Cambridgeshire[27]; three draughtsmen, one of wood, the other two of walrus tusk, carved with various quaint subjects; and several brooches.

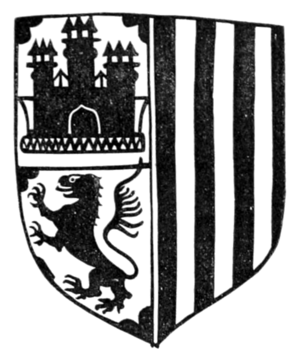

Only two seals have been added to the collection. One of them, the seal of Wangford Hundred in Suffolk, is here represented. It is identical in workmanship with that of South Erpingham Hundred, in Norfolk, already in the Museum. The other is a small personal seal of William de Clare, not one of the illustrious family who bore that name, but probably a native of the town of Clare in Suffolk. This seal was found near Farndish, in Northamptonshire, and presented by Mr. A. C. Keep.[28]

The ornamental tiles have been increased by donations from the Rev. John Ward, the Rev. Dr. Wrench, the Rev. E. Turner, Mr. Albert Way, and Mr. Greville Chester.

Among works of Foreign Mediæval Art may be mentioned a fine Limoges enamelled crozier of the thirteenth century; a processional cross of curious workmanship; a quadrangular plate of brass, being a portion of a monument of an abbot or bishop; two slabs of stone, portions of incised monuments of the fourteenth century and French workmanship; and several Italian and Spanish Majolica dishes. The brass above-mentioned is of Flemish workmanship[29] and is faithfully represented in Boutell's "Monumental Brasses of England:" the date appears to be about 1360. This as well as the two monumental slabs, formed part of the collection of the late Mr. Pugin.

One of the Spanish dishes is interesting from the arms it bears, which are represented in the annexed woodcut (see next page). They appear to be Castile and Leon quarterly, dimidiated and impaled with Arragon, It seems most probable that they are the arms of Eleanor, daughter of Pedro IV. King of Arragon, and queen of John I. King of Castile and Leon. This princess was married 1375 and died 1382, between which dates it is most likely that this dish was made. It is not improbable that our specimen may have been made in the Balearic Isles, then under the dominion of Arragon, as it is from one of them, Majorca, that the Italian Majolica derived its origin and name.

In concluding this inventory, I will here venture to call the attention of arhæologists to some branches in which the National Collection is most deficient, viz,: stone implements found in England or Wales, British urns, and Saxon antiquities of every kind, especially glass vessels.

It is very unsatisfactory, on looking over the early Minutes of the Society of Antiquaries, or volumes of the Archæologia, to note how few of the more interesting objects there described are now to be found. Whether it is owing to neglect, or fire, or any other casualty, that they have disappeared, it matters not to the archæologist, they are equal]y beyond his reach. It is in a public Museum alone that such things can be safely preserved or easily consulted.

AUGUSTUS W. FRANKS.

British Museum, March, 1854.

- ↑ An interesting; account of these discoveries will be found in "A Record of Farley Heath, by Martin F. Tupper, Esq" Guildford, 1850. See also Arch. Journ., x. 166.

- ↑ Arch. Journ., iii. 157.

- ↑ Sussex Archæol. Collections, ii. 270.

- ↑ Vide Horsfield's History of Lewes.

- ↑ Arch. Journ. ix. 336.

- ↑ Arch. Journ. x. 248.

- ↑ Mr. Nevill's Sepulchra Exposita, p. 2.

- ↑ Vide Arch. Journ., ix. 302, x. 69. and Journ. of Arch. Assoc., iii. 9.

- ↑ De Bello Gallico, lib. v.

- ↑ Arch. Journ., x. 367.

- ↑ Similar to Arch. Journ., iv. 329, Fig. 6.

- ↑ Engraved in Archæologia, xxxiii. pl. 15. See Arch. Journ., iii. 159; the torc was exhibited at the Lincoln meeting.

- ↑ Arch. Journ. x. 259.

- ↑ Lincoln Volume, p. xxviii. For inscriptions of a similar form, see Steiner, Codex Inscr. Rheni. Nos. 315 and 432.

- ↑ Arch. Journ., x. 64.

- ↑ Arch. Journ., vii. 70, 175.

- ↑ Engraved in Arch. Journ. x. 259, where the description of the two dagger-sheaths has been inadvertently transposed in the plate.

- ↑ Journ. of Arch. Assoc. ii. 346.

- ↑ Smith's Collectanea, ii. pl. xiv. fig. 6.

- ↑ Horsfield's Lewes, pl. iv. fig. 4.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., viii. 100.

- ↑ Vol. xxx. p. 10.

- ↑ Arch. Journ. ix. 388.

- ↑ Notice des Emaux du Louvre, No. 31. Engraved in Du Sommerard, Atlas des Arts du Moyen Age, ch. xiv. pl. iii.

- ↑ Similar to one engraved in Journ. of Arch. Assoc. v. 28.

- ↑ Arch. Journ. ix. 390.

- ↑ Arch. Journ. x. 262.

- ↑ Arch. Journ. x. 369.

- ↑ Arch., Journ., x. 163