Archaeological Journal/Volume 2/Notices of New Publications: Costum-Buch fur Kunstler and Trachten des Christlichen Mittelalters

Notices of New Publications.

Amongst the numerous valuable works recently published in Germany, in illustration of various subjects of archæological research, there are few which present more attractive features, or better deserve to be known and appreciated in England, than the publications here brought before the notice of our readers. In the detailed investigation of the usages of life in former times, and of the minor circumstances to which, at first sight, little importance may be attached, the student of middle-age antiquities constantly feels how requisite it is to be enabled to form a comparison of the fashions or peculiarities familiar to him in his own country, with those of neighbouring nations. By this means alone can a clue be gained to the real intention of many interesting details, which are now only to be traced imperfectly amongst the few examples preserved in England, but are fully illustrated by ancient memorials on the continent; by this means, also, can a just appreciation be formed of the distinctive conventional peculiarities exhibited in the decorative or artistic productions of various nations and periods. The influence of political relations with several countries of Europe operated not less than the spirit of mercantile enterprise, in giving to the arts, and fashions, and costume of our country, a complexion in which foreign peculiarities are continually to be traced. Whilst our forefathers received by way of Italy or the Low Countries, splendid tissues of eastern manufacture, or armour of proof and weapons wrought at Milan or in Spain, their frequent intercourse with France and Flanders, the long duration of the Crusades, and the wars which arose from the claim asserted by our sovereigns to the succession of Philip de Valois, still more, perhaps, the influence of foreign alliances, brought into England at different periods the elegancies and luxuries of other climes. In regard especially to costume it is obvious that numberless novelties must have been successively introduced under the influence of the Queens of England; thus, if we investigate the origin of the eccentric fashions of the close of the fourteenth century, the crackowe shoes, and jagged tippets of the times of Richard II., we should seek it in his alliance with a princess of Bohemia; as likewise we must attribute to the influence of Katherine of France, and Margaret of Anjou, the picturesque fashions of female attire, prevalent during the succeeding century. Costume, correctly understood, supplies the key to the Chronology of Art, and the utility of all works which, like the interesting publications produced at Dusseldorf and Mannheim, afford the means of comparing authentic examples in various countries of Europe, must be fully recognised.

These two publications are much to be commended as affording a large amount of information at a very moderate price. The Costüm-Buch is issued in numbers, each containing four plates in outline, which may be obtained in this country for one shilling. The subjects are, in both works, selected from tombs, illuminations in MSS., or other authentic authorities, but the plates in the Costüm-Buch are very inferior in execution to those given by M. de Hefner; they are in many instances etched with a degree of freedom incompatible with accuracy of detail, and not a few subjects have been borrowed, without acknowledgment, from the faithful representations given by Stothard, from Willemin, and other recent publications. It is manifestly advantageous that the valuable information which in costly publications is too frequently stored away beyond the reach of the student, should be diffused and rendered more generally available in a less expensive form, but the source whence it has been derived should in every case be acknowledged, as well for facilities of further research, which many may desire, as because the concealment is not compatible with good faith or good feeling. No text, however, has hitherto been given with the Costüm-Buch, beyond a concise statement of the date of the original subject, or the place where it exists, with indications, in some cases, of the colouring; and it may be hoped, that the authority which has supplied each plate may ultimately be recorded.

M. de Hefner, with the assistance of a number of artists and antiquaries in different parts of Europe, has commenced a work superior in interest and artistic character to any which have hitherto appeared on the subject of costume. The representations of the ancient monuments of art, the stately monumental effigies of Germany, and many other memorials, wholly unknown to the English antiquary, are given in carefully detailed outlines, which bear the stamp of conscientious accuracy; and, as far as our acquaintance with the originals enables us to judge, are designed with a degree of fidelity rarely shewn in similar publications. They have been almost exclusively selected from examples hitherto unpublished; the series is accompanied by an able introductory essay on the chief peculiarities of secular and sacred costume at different periods, and detailed descriptions of the plates; it is divided into three portions, the first of which comprises costume from the earliest times to the thirteenth century; the second exhibits the peculiarities of the fourteenth and fifteenth; and the third division is devoted to the sixteenth century. The text may be procured either in French or German, and copies carefully and splendidly coloured are on sale, but the price of each number, containing four plates, (about 20 francs, or one pound, if procured in London,) places the illuminated copies beyond the reach of most purchasers; the uncoloured plates, however, accompanied by a careful description of the colouring of every portion, may amply suffice, and are attainable at the price of two francs, or in England shillings, for each number.

It would not be easy to convey a notion of the variety of examples of ancient art which have supplied materials for this collection. In the rich and unexplored treasuries of mediæval sculpture, the churches of Germany, numerous striking specimens have been selected; we may here admire the grandeur of the sepulchral memorials of that country, and perceive the original intention of the canopy of tabernacle-work, sometimes termed a hovel, housing[1], or dais, which appears over the heads of some recumbent monumental figures in England. The tombs of Edward III., of Richard II. and his Queen, and of several other distinguished personages, afford examples of this feature of decoration; it is not improbable that it was introduced from Flanders or Germany, and in those countries we find it appropriately employed, the effigy being frequently placed in an erect position, as a mural, not a recumbent memorial. It may deserve enquiry whether in adopting a continental fashion of placing the figure in a kind of niche with shrine-work on either side and a richly purfled canopy, we did not disregard the propriety of its original use, and retaining our own usage of the recumbent portraiture of the deceased, surround it with ornamental accessories which properly belonged to the erect figure. A specimen of the earlier English effigies in the cross-legged attitude, peculiar, as it would appear, to our own country, has been added by M. de Hefner to his curious collection. It is the figure assigned to Sir Robert Harcourt, in Worcester cathedral, and engraved from a drawing communicated by Mr. Robert Pearsall, of Willsbridge, who has contributed some other subjects, comprised in this work, amongst which is the remarkable effigy of Sir Guy de Brian, preserved in Tewksbury abbey church.

Illuminated MSS., painted glass, and various other productions of art, have afforded well-chosen examples; M. de Hefner has also brought together representations of some of those interesting relics, which are associated with the memory of men eminent for great deeds or sanctity of life. At the present time, when sacred costume is a subject of much research, the chasuble of St. Willigisius, bishop of Mayence, A.D. 975, to whom the erection of the cathedral of that city is attributed, presents no slight degree of interest. In the same church is still to be seen a beautiful pastoral staff, an enamelled work attributed to the eleventh century, and similar to the curious specimens of the work of Limoges, which are to be seen in the galleries recently opened in Paris at the Louvre, and Palais des Thermes.

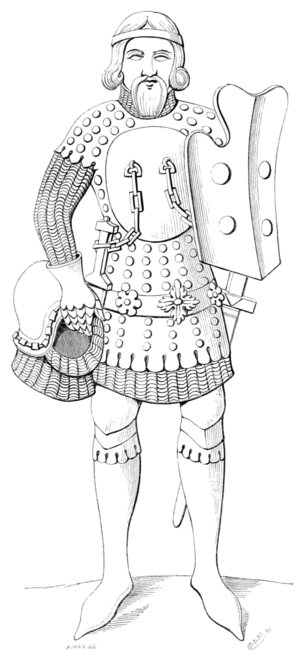

The illustrations of military costume contained in M. de Hefner's interesting series, are not less curious and novel than the subjects of a sacred character. He has given representations of a visored bacinet, of which he is the possessor, which has the extraordinary projecting beak, according to a fashion which prevailed in England during the reign of Richard II.; and it still retains the vervilles, or small staples, which wore used in lacing on the mailed camail to the head-piece, at that period. These, which may be noticed on many of our sepulchral effigies, are wanting in the specimens preserved in the Musée de l'Artillerie, at Paris, but the curious Neapolitan bacinet in the armoury at Goodrich court still retains them. The visor was removed whenever the grand heaume was worn over the bacinet, surmounted by the stately crest, the pendant lambrequin, and other accessory ornaments which were introduced with such picturesque effect in German heraldry. As an occasional defence a kind of nasal was devised, of which no example has hitherto been noticed in England. Of this the monumental figure of Ulrich Landschaden, knight, who died 1369, and was interred in the church of Neckarsteinach, near Heidelberg, has supplied a very curious illustration, as seen in the woodcut here given. It will be perceived that to the mailed throat-guard, a small piece of plate, of a shape fitted to the nose, was attached; this, when brought up into place as a nasal[2], was fastened to the forepart of the bacinet, by means of a staple and pin which passed through it. It is remarkable to find at so late a period in the fourteenth century so small an admixture of plate, as appears in the armour of this figure. With the exception of the bacinet, the gauntlets and the genouillères, the defences are wholly of mail, and the shape of the body is expressed in such a manner as to make it evident that no plastron, or breastplate, was worn in this instance with the hauberk. The close-fitting jupon, called in Germany Lendner, the arm-holes of which are singularly jagged or foliated, is buttoned down the front, an uncommon fashion, of which a very curious example is to be found at Abergavenny, in Monmouthshire. It is the effigy of a knight of the De Hastings family, now placed under one of the arches on the south side of the choir, opening into the Herbert chapel; in France no example of this buttoned just-au-corps has hitherto been noticed[3].It deserves notice that the sword has a chain attached to its hilt, appended apparently to the breast of the hauberk, so that if the weapon slipped out of the grasp of the combatant it might readily be recovered. The fashion of wearing chains, usually attached to mammelières, or ornamental bosses on the breasts, appears to have been very prevalent in Germany; an example of their use in England is supplied by the curious effigy at Alvechurch, Worcestershire, which represents a person of the Blanchfront family, t. Edward III.: in this instance two chains appear, the one which proceeds from the left breast being connected with the sword-hilt, and the second attached, apparently, to the scabbard[4]; occasionally these chains were linked to the dagger, or even, as seen in the sepulchral brass of Sir Roger de Trumpington (A.D. 1292), to the outer head-piece, or heaume. In that example, however, the chain is attached to the girdle. An allusion to this usage occurs in the French romance, entitled "le Tournois de Chauvenci," Written about A.D. 1285.

"Chascun son hiaume en sa chaaine,

Qui de bons cous attent l'estraine." v. 3543.

For chausses, or long hose of chain-mail, we find in these examples leg coverings, probably formed of leather: Chaucer mentions "jambeux of coorbuly," or jacked leather, and defences of that nature may frequently be noticed in examining English monumental effigies of the reign of Edward III.

It may be sufficiently seen from these examples, how instructive and interesting is the series which is in the course of publication by M. de Hefner. We must, however, present to our readers one more example of German art, of the most splendid character. There is perhaps no other work of middle-age sculpture which exhibits so much dignity of expression, accompanied by the richest accessories of costume. The figure represents Giinther of Schwarzburg, King of the Romans, who died in 1349, not as his warlike aspect would have led us to imagine, in the front of the battle, but a victim to poison. It was raised shortly after his decease by his partisans, and still exists in the choir of the cathedral of Francfort on the Mein. It is elaborately painted, to give the reality of life, as nearly as might be, to so majestic a portraiture. The general usage of colouring monumental effigies, of whatever material they might be formed, appears to have prevailed at all periods in Germany, as well as in England; in France the effigies of white marble, sculptured during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, were frequently left without any such decoration. The nasal attached to the camail is here again to be noticed, the blue surcoat is powdered with golden lions, and lined with the white fur called Kleinspalt, which must not lie confounded with the Imperial ermine. The most singular portions of the armour are the defences which are laid over the sleeves of mail, and those which supply the place of greaves. M. de Hefner describes them as formed of cuir-bouilli, formed in longitudinal bands, which are gilt, with intervening rows of gilt studs, serving probably not only as fastenings of the rivets, but also as a partial protection from a blow. Examples of armour of a similar kind are supplied by the effigy in the north aisle of the nave at Tewksbury church, and that of Sir Otho de Grandison, at Ottery St. Mary, Devon. Similar defences were used also in Italy, as shewn by sepulchral figures in the church of the Santa Croce, at Florence, (date about 1357,) which present likewise examples of the use of chains and mammelières, and of the nasal, above mentioned. (See Mr. Kerrich's interesting drawings preserved in the British Museum; Add. MS. 6728. f. 130.) Several sepulchral brasses also existing in England, exhibit defences formed with rows of small round plates; armour wholly formed in such a manner was in use as early as the thirteenth century, as is shewn by the figure of a knight, copied by Strutt from a MS. in the British Museum[6]. De Comines relates that the dukes of Berry and Charolois, in their expedition against Paris in 1465, "chevauchoient sur petites hacquenées à leur aise, armez de petites brigandines fort légères; pour le plus encore disoient aucuns qu'il n'y avoit que petits cloux dorez par dessus le satin, afin de moins leur peser[7]." In later times a defence similarly formed but of more rude description, appears to have been called a "peny platt cote," and a curious specimen of horse-armour, composed of round plates riveted upon leather is preserved in the Great Hall, at Warwick Castle.

- ↑ By the indenture for the construction of the tomb of Anne, Queen of Richard II., in Westminster abbey, Nicholas Broker and Godfrey Prest, coppersmiths, of London, covenanted to make "tabernacles appellés Hovels, ove gabletz às testes, ove doublesjambes à chescune partie." A.D. 1395. Rymer, vol. vii. The hovels still remain, but the double jambs, or tabernacle-work at the sides, have been torn away.

- ↑ Another specimen of this curious nasal is given by Müller, in his plate of Johan von Falckenstein, 1365. Beiträge zur Kunst, p. 59.

- ↑ The jupon was sometimes laced up in front, instead of being buttoned. M. de Hefner gives a good example of this fashion, it is the figure of Weikhard Frosch, who died 1378. XIV. Cent. pl. 49.

- ↑ Stothard's Monumental Effigies. See also the sepulchral brass, apparently of Flemish execution, which commemorates Ralph de Knevyngton, 1370, at Avely, in Essex. (Waller's Brasses.) The chain attached to the sword-hilt appears on the great seals of Edward III. In the accounts of the silversmith of John II., king of France, 1352, a charge occurs " pour forger—ij. mamellières, et deux chaiciies pour icelle mamellières." The double chain from the right breast, with a single chain depending from the left, appears on two curious effigies in Alsace, date about A.D. 1344. Schoepflin, Alsatia Illustr. pp. 533, 633. In the "Ordonnance comment on soulloit faire anciennement les Tournois, (Colombière, t. i. 48, and Due. in Joinv. Diss. vii. 183.) amongst the requisite harness for the knight are included "deux chaines à attachier à la poitrine de la cuirie, une pour l'espée, et l'autre pour le baston," which in the English version, Harl. MS. 6149, f. 46, is thus rendered, "item, ij. thengeis knet to the brest of the curie, one for the suord, the tother for the bastone."

- ↑ Sonic kind of breast-plate had been used as early as the reign of Henry II., as may be gathered from the lines of William le Breton, who describing a tilting match, in which Richard Cœur de Lion, at that time earl of Poictou, took part, says, that in the fury of the encounter the ashen lance pierced through shield, gamboison, and breast-guard, wrought with triple tissue; so that at last "vix obstat ferro fabricata patena recocto," the little plate of proof scarce could resist the thrust. The pair of plates were used in England as early as 1331. It appears by the Inventories of the Exchequer that in that year Edward III. ordered restitution of the armour of Roger, earl of March, to his son Esmon de Mortemer; and amongst the items occur "une peire des plates covertz de rouge samyt. vj. corsets de feer," &c. Possibly the small breast-plates represented as worn by the Bamberg warriors were termed "corsets."

- ↑ Royal MS. 2 A. XXII. Strutt's Dresses, vol. ii. pl. lxvi. Shaw's Dresses.

- ↑ Memoires, liv. 1. c. vi.