Archaeological Journal/Volume 2/The Legend of St. Werstan, and the first Christian Establishment at Great Malvern

THE LEGEND OF SAINT WERSTAN,

AND THE FIRST CHRISTIAN ESTABLISHMENT AT GREAT MALVERN.

On the northern side of the choir of the ancient priory church of Great Malvern, in Worcestershire, three large windows, which compose the clerestory, still exhibit, in the original arrangement, a very interesting series of subjects taken from sacred as well as legendary history. These windows consist of four lights, which are divided into two almost equal stories by a transom; and the painted glass with which they are still, in great part, filled, appears never to have been re-leaded or disturbed, although in its present fractured and decaying condition, it greatly needs some judicious measures which might preserve it from further injuries. The window which is nearest to the northern transept, and most remote from the eastern end of the church, presents a very curious series of subjects, and of some of these it is proposed to offer to our readers a detailed description. They illustrate the origin of a Christian establishment in the wild woodland district, which, at an early period, contributed to render the hill country of Worcestershire an almost impenetrable fastness, and boundary towards the marches of Wales. It was by a very small beginning that Christianity found an entrance into this savage country, but the primitive introduction of Christian worship, to which it will be my endeavour to draw the attention of our readers, ultimately led the way to the foundation of an extensive religious establishment, the Benedictine monastery, which, although considered as a cell to Westminster, occupied in this country a very important position. An interesting evidence of the beneficial tendency of a monastic institution, situated, as was the priory of Great Malvern, in a remote and inaccessible district, is afforded by the letter of remonstrance, addressed by the pious Latimer, then bishop of Worcester, entreating that an exception might be made in its favour, at the time of the general dissolution of religious houses[1].

The documentary evidences, chartularies, and records, which might have thrown light on the early history of Great Malvern, have either been destroyed, or yet remain stored away in concealment, amongst the unexamined muniments of some ancient family. Some fortunate research may hereafter bring to light these ancient memorials; at the present time little is known even of its later history, and the legend of the circumstances under which, in Anglo-Saxon times, the first Christian establishment was here made, is recorded only on the shattered and perishable glass, which has escaped from the successive injuries of four centuries. The priory church of Great Malvern was erected by the hermit Aldwin, according to Leland's statement, about the year 1084; the Annals of Worcester give the year 1085 as the date of the foundation. Some portions of the original fabric still exist; the short massive piers of the nave, and a few details of early Norman character, are, doubtless, to be attributed to that period. It appears by the Confirmation charter of Henry I., dated 1127, that the monks of Great Malvern then held, by grant from Edward the Confessor, certain possessions which had been augmented by the Conqueror; but there is no evidence that, previously to the Conquest, any regular monastic institution had been there established. The evidence which was given by the prior, in the year 1319, may be received as grounded, not merely on tradition, but on some authentic record preserved amongst the muniments of the house. He declared that the priory had been, for some time previously to the Conquest, "quoddam heremitorium," a certain resort of recluses, founded by Urso D'Abitot, with whose concurrence it subsequently became a monastic establishment, formed and endowed by the abbot of Westminster[2]. It is not, however, my present intention to enter into the subject of the foundation or endowment of the priory, but to call attention to the singular and forgotten legend of the hermit saint, who first sought to establish Christian worship in the impenetrable forest district of this part of Worcestershire.

Several writers have described, in greater or less detail, the remarkable painted glass, of which a considerable portion still remains in the windows of Great Malvern church; of few churches, indeed, have such minutely detailed accounts been preserved, noted down long since, at a time when the decorations had sustained little injury. The full descriptions, which were taken by Habingdon, are for the most part accurate and satisfactory, and afford a valuable source of information; a mere wreck now remains of much which attracted his attention, and has been preserved from utter oblivion in the notes compiled by him during the reign of Charles I.[3] It is however very singular that he wholly overlooked, as it would appear, the remarkable commemorative window, to which the present notice relates; and Thomas, Nash, and other subsequent writers, have contented themselves with giving a transcript or abstract of Habingdon's notes, without any comparison with the original painted glass still existing. They have in consequence neglected the most curious portion of the whole, and it will now be my endeavour to set before our readers this feature of the ancient decorations of this interesting church, as a singular example of the commemorative intention of such decorations, and, in default of direct historical or documentary evidences, an addition to the information which we possess, respecting the progressive establishment of Christian worship in our island, in early times.

Leland, who appears to have visited Great Malvern, in the course of the tour of investigation pursued by him during six years, and who had the opportunity of consulting the muniments, to which the commission of enquiry, granted to him under the Great Seal, in the year 1533, afforded him freedom of access, has noted down that nigh to the priory stood the chapel of St. John the Baptist, where St. Werstan suffered martyrdom[4]. He had, perhaps, examined the singular subjects in the northern window of the choir, a memorial replete with interest to a person zealously engaged on such a mission of historical enquiry, and had listened in the refectory to the oral tradition of the legendary history to which these representations relate, or perused the relation which was then preserved in the muniment chamber of the priory. Leland is the only writer who names the martyr St. Werstan, or makes any allusion to the connexion which appears to exist between his history and the foundation of the religious establishment at Great Malvern. It is, however, certain, from the place assigned to the four subjects illustrative of the incidents of his life, in the window destined to commemorate the principal facts of that foundation, that in the fifteenth century, when this painted glass was designed, the monks of Great Malvern accounted the "certain hermitage," according to the statement of the prior, in the year 1319, as above related, to have been the germ of that important and flourishing establishment, which at a later time had taken a prominent place amongst the religious institutions situated on the western shore of the Severn.

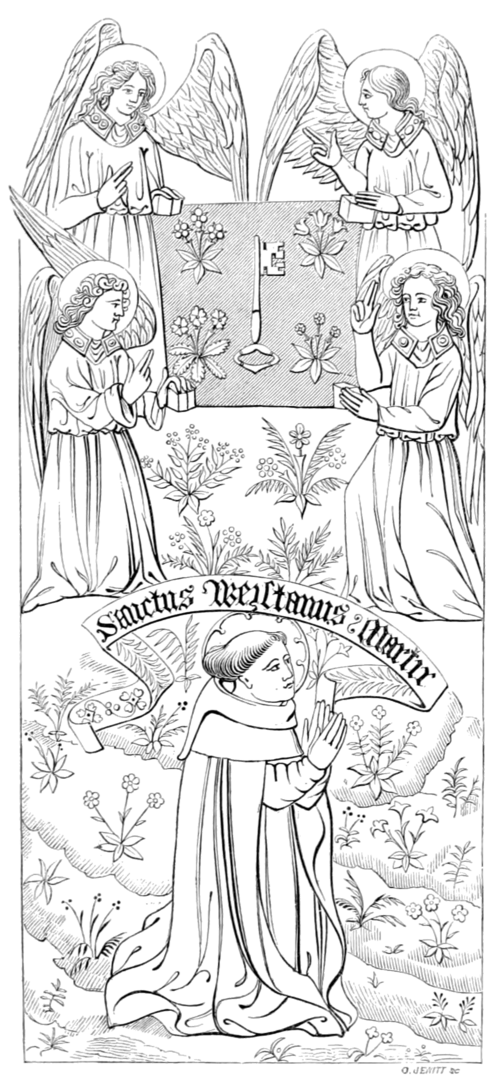

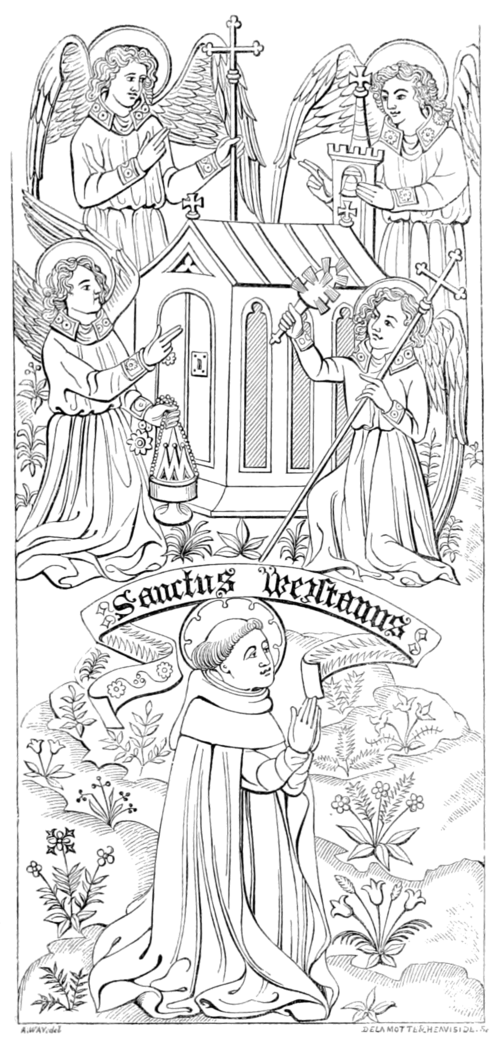

The remarkable painted glass, to which I would call attention, is to be found in the upper division or story of the clerestory window, nearest to the Jesus chapel, or northern transept. In the elevated position occupied by these representations, they appear scarcely to have attracted notice, the figures being mostly of small dimension; and to these circumstances it is perhaps to be attributed that Habingdon and the writers of later times have wholly neglected so singular a series. The painted glass, which is preserved in the choir of this church, appears to have been executed towards the year 1460: some changes have, in recent times, been made, and the windows on the southern side have been filled with portions collected from the clerestory of the nave, which was of somewhat later date than the choir. The construction of the church, as augmented and renovated in the Perpendicular style, appears to have commenced towards the middle of the fifteenth century; and it is to prior John Malverne, who is first named in the register of Bishop Bourchier, in 1435, that the commencement of this new work may be attributed. Habingdon has recorded that in the window of the clerestory of the choir, on the northern side, nearest to the east end, the kneeling figure of that prior was to be seen, with an inscription commemorative of his benefaction. It no longer remains, as described by Habingdon, but it is possible that the fragment which may still be noticed in the lower part of that window, being the head and upper part of the figure of a Benedictine monk, may be the portraiture of prior Malverne, the founder of the new choir: and it may readily be distinguished by the inscribed scroll over the head, O felix Anna, pro me ad xp'm ex ora. The following inscription formerly recorded his benefaction, Orate pro anima Johannis Malverne qui istam fenestram fieri fecit, and although it is not certain that such requests for prayers on behalf of the soul of the benefactor were not, in some instances, thus inscribed during his life-time, some persons will probably take the pious phrase as an evidence that the window was not completed until after the decease of the prior, which occurred about the year 1449. But some further circumstances, in regard to the painted glass which is preserved in the windows of the choir, will be hereafter noticed, in the endeavour to ascertain its date; I will now proceed to describe the four subjects which comprise the legendary history, as I am led to suppose, of St. Werstan, exhibited in the upper story of the window nearest to the northern transept. In the first pane is to be observed a representation apparently composed of two pictures, forming one subject; in the upper part are seen four angels, with golden-coloured wings, vested in amices and albs, the apparels of the former being conspicuous, and presenting the appearance of a standing collar. Each of these angels has the right hand elevated in the Latin gesture of benediction; and they rest their left hands on the boundary stones placed at the four angles of a square verdant plot, which appears in that manner to be set out and defined, being a more green and flowery spot than the adjacent ground, which seems to represent a part of the Malvern hills. In the centre of this piece of ground, thus marked out by the angels, appears a large white key. In the lower division of the same pane appears a figure kneeling, and looking towards heaven; a hill, formed of several banks or terraces one above another, appears as the back-ground, and over his head is a scroll thus inscribed, Sanctus Werstanus Martir. He is not clad in the Benedictine habit, like other figures in the adjoining windows, but in the russet-coloured cappa, or full sleeveless mantle, with a round caputium, or mozzetta, to which is attached a hood. Under the mantle may be distinguished the scapulary: the head is bare, and the hands are raised in adoration. There can, I think, be little question, that this first subject was intended to represent a celestial vision which indicated to the hermit, who had fled from troubles or temptations to the wilds of the Malvern hills, the spot where he should construct an oratory, which would ultimately lead to the foundation of an important Christian institution in those dreary wastes. The import of the silver key at present remains unknown, for the legend of St. Werstan is lost, and even his name has not been handed down in any calendar of British Saints, but the signification of this interesting representation can scarcely be mistaken; the heavenly guidance, which fixed the wanderings of the pious recluse in the woodland waste of this hill country of Worcestershire, and pointed out the site of the primitive Christian foundation in that district, appears undeniably to be here set forth and commemorated.In the next pane may be noticed a similar twofold disposition of the subject represented. In the lower part appears the same hermit, clad in russet as before, the epithet Martir being, perhaps accidentally, omitted in the inscription. In the superior division are again seen the four angels vested in like manner in albs, which have apparels on the sleeves, over the wrists; and these celestial messengers are engaged in the dedication of the oratory, which, as it may be supposed, had been raised by St. Werstan on the spot miraculously pointed out to him in the vision. The angels elevate their right hands, as before, in benediction; one bears a processional cross; another, who approaches the closed entrance of the chapel, bears the thurible, and seems prepared to knock against the door, and cry aloud, according to the impressive ancient ritual of the Latin church, "Lift up your heads, O ye gates, and be ye lifted up, ye everlasting doors, that the King of Glory may come in!" A third angel bears the cross-staff, and raises the aspergillum, or hyssop, as if about to sprinkle with holy water the newly completed edifice; whilst the fourth touches the bell, which is suspended in an open turret, surmounted by a spire and finial cross. The roof of the chapel is coloured blue, as if to represent a covering formed of lead. In this pane we must at once recognise the representation of a miraculous dedication of the chapel, which had been built by the hermit Saint in obedience to a vision from above, and was now consecrated by the same ministering spirits who had been sent forth to direct him to undertake its construction. It is interesting to compare this subject with the curious drawing, preserved at Cambridge, which may be seen in a series of representations illustrative of the life of Edward the Confessor; amongst these occurs the miraculous dedication of the church of St. Peter, at Westminster, by the arch-apostle in person, according to the legendary history; St. Peter is there seen accompanied by angels, who perform the services of the attendant acolytes, in singular and close conformity with the curious representation at Great Malvern, above described.

The drawings in question exist in a MS. in the library at Trinity College, and appear to have been executed towards the commencement of the fifteenth century. In the third compartment of the window the eye is at once struck by the stately aspect of a regal personage, a figure of larger dimension as compared with those which have been described: he appears vested in a richly embroidered robe lined with ermine, a cape of the same, and the usual insignia of royalty. In his right hand he holds a charter, to which is appended the great seal, bearing the impression of a cross on red wax, and apparently is about to bestow a grant upon a person who kneels at his feet. The king is at once recognised by the inscribed scroll, Sc's Edwardus rex; the figure of the suppliant, to whom the charter is accorded, is represented as of much smaller proportion than that of the sovereign, in accordance with a conventional principle of design in old times, by which persons of inferior station were often represented as of diminutive size, in comparison with their more powerful neighbours. Over the head of this smaller figure is a scroll, which bears the following inscription, Will' m': Edwardus: It does not appear, in the absence of all legendary or historical evidence, who was the person thus designated, upon whom a grant was conferred by the Confessor, and who here appears as connected with the history of St. Werstan. He is clad in a sleeved robe and hooded cape, the former being blue, and the cape bordered with white: it is not properly the monastic habit, and it differs from that in which St. Werstan appears, as before described. It may be conjectured that the hermit, disturbed in his peaceful resting place upon the Malvern heights by some oppressive lord of the neighbouring territory, had sent a messenger to intercede with St. Edward, and obtained by royal charter lawful possession of the little plot whereon the celestial vision had led him to fix his oratory. Certain it is, as recorded in the charter of Henry I., dated 1127, that amongst the possessions of Great Malvern were numbered lands[5] granted by the Confessor, although no regular monastic establishment appears to have existed previously to the Conquest. It seems therefore rea sonable to conclude from the introduction of the subject now under consideration, in connection with the circumstances of the legend of that saint, that, according to received tradition, the period when St. Werstan first resorted to this wild spot, and established himself on the locality marked out by a heavenly vision, was during the times of the Confessor. The fourth, and last subject of the series, which appears in the upper division of this remarkable window, appears to represent the martyrdom of St. Werstan the hermit, and the chapel or oratory, which was the scene of that event, described by Leland as situated near to the Priory. On the steep side of the Malvern heights are represented, in this pane, two small buildings, apparently chapels: the upper one may, doubtless, be regarded as the same miraculously dedicated building, which appears in the second pane; from its roof springs the bell-turret and spire, but precise conformity in minor details has not been observed in these two representations. At one of the windows of the oratory is here to be seen the Saint, who puts forth his head, bleeding and bruised, whilst on either side stands a cruel murderer, prepared with sword upraised to strike the unoffending recluse. These miscreants are clad in gowns which are girt round their waists, and reach somewhat below their knees; the scabbards of their swords are appended to their girdles, and on their heads are coifs, or caps, similar in form to the military salade, but they do not appear to be armour, properly so called. These may possibly, however, represent the palets, or leathern headpieces, which were worn about the time when this painted glass was designed, as a partial or occasional defence. Be this as it may, it deserves to be remarked that the short gown and coif-shaped head covering is a conventional fashion of costume, in which the tormenter and executioner are frequently represented as clothed, in illuminations and other works of medieval art. An illustration of this remark is supplied by the curious embroidered frontal and super-frontal, preserved in the church of Steeple Aston, Oxfordshire, which were exhibited at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Association at Canterbury. The subjects portrayed thereon are the sufferings of Apostles and martyred Saints: the work appears to have been designed towards the early part of the fourteenth century; and the tormenters are in most instances clad in the short gown and close-fitting coif. Beneath, not far from the chapel, wherein the martyr is seen, in the Malvern window, appears a second building, not very dissimilar to the first in form, but without any bell-turret and spire: possibly, indeed, so little were minute propriety and conformity of representation observed, the intention may have been to exhibit the same building which is seen above, and a second occurrence which there had taken place. This oratory has three windows on the side which is presented to view, and at each appears within the building an acolyte, or singing-clerk, holding an open book, whilst on either side, externally, is seen a tormenter, clad in like manner as those who have been noticed in the scene above; they are not, however, armed with swords, but hold bundles of rods, and seem prepared to castigate the choristers, and interrupt the peaceful performance of their pious functions. With this subject, the series which appears to represent the history of the martyr St. Werstan, closes, and in the four compartments of the lower division of the window, divided by the intervening transom, are depicted events recorded and well known, in connection with the foundation of Great Malvern, namely, the grant and confirmation conceded by William the Conqueror to Aldwin, the founder; the grant to him by St. Wolstan, bishop of Worcester; and the acts of donation by William, earl of Gloucester, Bernard, earl of Hereford, and Osbern Poncius; benefactions which materially contributed to the establishment of this religious house. Of these, curious as the representations are, I will not now offer any description; the circumstances, to which they relate, are detailed in the documents which have been published by Dugdale, Thomas, and Nash. No allusion has hitherto been found in the legends of the saints of Britain, or the lists of those who suffered for the faith within its shores, to assist us in the explanation of the singular subjects which are now, for the first time, described; they appear to be the only evidences hitherto noticed, in relation to the history of St. Werstan, and the earliest Christian establishment on the savage hills of Worcestershire. In this point of view, even more than as specimens of decorative design, it is hoped that this notice may prove acceptable.It is so material, wherever it may be feasible, to establish the precise age of any example either of architectural design, or artistic decoration, that a few observations will not here be misplaced, in the endeavour to fix the dates, both of the fabric of the later portions of Great Malvern priory church, and of the painted glass which still decorates its windows. The work of renovation or augmentation had commenced, as it has been stated, under Prior John Malverne, towards the year 1450; and it progressed slowly, as we find by various evidences. It has been affirmed that the great western window was bestowed by Richard III., whose armorial bearings were therein to be seen; the nave appears to have been completed during the times, and under the patronage of the liberal John Alcock, whilst he held the see of Worcester, from 1476 to 1486. But in regard to the eastern part of the building, it is to be noticed that the dates 1453 and 1456, (36th Henry VI.) appear on tiles which formed the decoration not only of the pavement, but of some parts of the walls of the choir; being here used in place of carved wainscot, an application of fictile decoration, of which no other similar example has hitherto been noticed. The period at which the work had been so far completed, that the dedication of the high Altar, and of six other altars, might be performed, which took place probably on the completion of the choir and transepts, is fixed by an authentic record, hitherto strangely overlooked by those who have written on the history and antiquities of Malvern, and now for the first time published. This document is to be found in the Registers of Bishop Carpenter, the predecessor of Bishop Alcock in the see of Worcester. They are preserved amongst the chapter muniments in the Edgar Tower, at Worcester. This evidence has possibly been overlooked on this account, that those who searched for documents in relation to the date of the later building, did not bear in mind that no consecration of the new structure would take place, the church having been only embellished or enlarged; the only evidence therefore, to be sought in the episcopal archives, would be the record of the dedication of the altars, which is given in the Register as follows:

Registrum Carpenter, vol. i. f. 155. "Consecracio altarium in prioratu majoris Malvernie. Penultimo die mensis Julii, Anno Domini millesimo ccccmo sexagesimo, Reverendus in Christo pater et dominus, dominus Johannes, permissione divinâ Wigorniensis Episcopus, erat receptus in monasterium sive prioratum majoris Malvernie per priorem et Conventum ejusdem, cum pulsacione campanarum, et ibidem pernoctavit, cum clericis, ministris, et servientibus suis, sumptibus domus. Et in crastino die sequente consecravit ibidem altaria, videlicet, primum et summum altare, in honore beate Marie virginis, Sancti Michaelis Archangeli, Sanctorum Johannis Evangeliste, Petri et Pauli Apostolorum, et Benedicti Abbatis. Aliud altare in choro, a dextris, in honore Sanctorum Wolstani et Thome Herfordensis. Aliud in choro, a sinistris, in honore Sanctorum Edwardi Regis et Confessoris, et Egidii Abbatis. Quartum, in honore Petri et Pauli, et omnium Apostolorum, Sancte Katerine et omnium virginum. Quintum, in honore Sancti Laurencii, et omnium martirum, et Saneti Nicholai, et onmium confessorum. Sextum, in honore beate Marie virginis, et Sancte Anne, matris ejusdem. Et septimum, in honore Jesu Christi, Sancte Ursule, et undecim milia virginum."

The period, therefore, at which the work had so far progressed that the services of the church might take place in the choir of the new fabric, was the year 1460. It is worthy of observation, that in the great eastern window, a careful observer may discern, here and there, scattered as if irrespectively of any original design in the painted glass, several large white roses and radiant suns, which appear to be allusive to Edward IV, They seem to have been inserted in various places, after the window had been filled with painted glass, as they manifestly do not accord with the propriety of the design, which consists of subjects of New Testament history. The painted glass to which the present notice chiefly relates, namely, that which has been preserved in the northern clerestory windows of the choir, may be assigned to this same period, the later part of the reign of Henry VI., or commencement of that of Edward IV. There is a great pre- dominance of white glass, according to a prevalent fashion of the time: the skies are richly diapered, the alternate panes, or compartments, being red and blue; the figures are slightly shaded, but scarcely any colour, with the exception of yellow, is introduced.

It is not very easy to fix the positions of the seven altars, described in the record of their consecration. The high Altar, dedicated in honour of the Blessed Virgin, St. Michael the archangel, St. John the Evangelist, St. Peter, St. Paul, and St. Benedict, occupied the position wherein now is placed the altar-table. The two altars which are described as in the choir, were, probably, one at the eastern extremity of the north aisle thereof, dedicated in honour of St. Edward the Confessor, and St. Giles; and the second on the other side, where is now a vestry; this was dedicated in honour of St. Wolstan, and St. Thomas of Hereford. The fourth, dedicated in honour of St. Peter and St. Paul, may have been in one of the transepts, and the sixth, in honour of the Blessed Virgin, and St. Anne, in the lady chapel, eastward, which is now totally destroyed, unless indeed that building was erected subsequently to the choir. The seventh, dedicated in honour of Jesus Christ, St. Ursula, and the eleven thousand virgins, was in the southern transept. It seems not improbable that some change in the appropriation of these altars might have been made at some later period, for whilst the northern transept has been always traditionally called the Jesus chapel, the southern transept, long since wholly demolished, has been termed the chapel of St. Ursula. The tomb of Walcherus, the second prior, discovered in 1711, on the site of the cloisters, not far from the spot formerly occupied by the southern transept, is described as having been found about twelve feet from the chapel of St. Ursula[6].

In the map of the chace and hills of Great Malvern, which was supplied by Joseph Dougharty, of Worcester, for the work compiled by William Thomas, and published in 1725, under the title, "Antiquitates Prioratus majoris Malverne," it is to be noticed, that above the Priory church, a little higher up the hill, towards the Worcestershire beacon, appears a little solitary building, marked "St. Michael's Chapel." The position of the chapel, as it appears in this map, corresponds with the description which is found in Habingdon's notes on the windows of the church, as given by Thomas. In the lower part of the western window of the northern transept, or Jesus chapel, it is stated that there were to be seen the town and church of Malvern, and the chapel of St. Michael, situated on the side of the hill; and in the southern corner an archer in the chace, about to let fly a shaft at a hind[7]. Not a trace of this interesting subject is now to be distinguished. It must be observed that, although the Priory church, according to the account commonly received, was dedicated in honour of the Blessed Virgin alone, it appears from a passage in the Chronicle of Gervase of Canterbury, that it was dedicated in honour of St. Michael also; and Richard, "filius Puncii," in his grant of the church of Leche to Malvern, expresses, that the donation was made "Deo, et Sancte Marie, et Sancto Michaeli Malvernie[8]." The high Altar of the new fabric, according to the document given above, was also consecrated in honour of the Blessed Virgin, and St. Michael the archangel. These facts woidd lead to the supposition that the primitive oratory had been dedicated in honour of the Archangel, on account of the miraculous vision of Angels, who first directed St. Werstan to undertake the work, and by whose ministry it had been consecrated. Nor was the memory of the same celestial guidance lost, when a more stately fabric was erected near to St. Michael's chapel; the trace of it is preserved in the dedication of Aldwin's church to the Archangel, in the times of the Conqueror, as likewise in that of the high Altar, in 1460; and these facts seem to shew that the monks of Great Malvern, at all times, bore in mind, that the remote origin of that religious foundation was derived from the message of ministering spirits to the hermit Saint[9].

A singular difficulty presents itself in this endeavour to bring together the few obscure details which relate to the legend of St. Werstan. Leland, and Leland alone, makes mention of the chapel of St. John the Baptist, nigh to the Priory, as the scene of his martyrdom. No other notice whatsoever has been found of any chapel thus dedicated. The ancient parish church, which stood near to the Priory, at the north-western angle of the present cemetery, was dedicated in honour of St. Thomas the Apostle, and no evidence has been adduced to shew that any other chapel existed in the vicinity. May it be supposed that Leland wrote inaccurately in this instance, or that the chapel of St. Michael might have been dedicated also in honour of the Baptist, and occasionally designated by his name? The decision must be left to the more successful researches of those who take an interest in the history of the locality; it will suffice now to suggest, that the forgotten site of the hermit's primitive chapel may still perhaps be traced, situated not far above the Priory church. No tradition is connected with the spot; few even bear in mind that not many seasons have passed since it was commonly termed The Hermitage. It is only twelve or fifteen years since, that a gentleman named Williams, on his return from Florence, selected and purchased this picturesque site; he built thereon a dwelling, in the Italian fashion, and applied to it the name of the Grand Duke's Villa, Il bello sguardo. The neighbours now commonly call it Bello Squardo, or sometimes, I believe, Bellers' Garden, and certainly it was not there that the curious traveller, in search of the spot where Christian worship was first established on these hills, in Anglo-Saxon times, would have lingered on his ascent to St. Anne's well. The Hermitage, at the time when it so strangely lost its ancient name, appears to have been an old-fashioned building, little worthy of the notice even of an antiquary: it had been fitted up as a dwelling-house, probably, soon after the dissolution of monasteries. An ancient vault, or crypt, of small dimensions, fragments of dressed ashlar, and a few trifling relics, have from time to time been found: several interments in rudely-formed cists, or graves lined with stones, were also discovered, which seem to shew that the spot had been consecrated ground. Here, then, in default of tradition, or any more conclusive evidence, it may be credibly supposed that the simple oratory of St. Werstan had stood; here did he suffer martyrdom, and here was the memory of his example cherished by those whose labours tended to the establishment of Christian institutions in the wild forests of this remote district of our island. albert way.

- ↑ Cott. MS. Cleop. E. iv. f. 264: printed in new edit. Monast. Ang. iii. 450.

- ↑ Plac. coram Rege apud Ebor. term. Mic. 12 Edw. II. Monast. Angl.

- ↑ William Habingdon, or Habington, of Hindlip, Worcestershire, was condemned to die for concealing some of the agents concerned in the gunpowder plot. He was pardoned on condition that he should never quit the county, to the history and antiquities of which he subsequently devoted his time. There existed formerly a MS. of these collections in Jesus College library, Oxford. In the library of the Society of Antiquaries there is a transcript made by Dr. Hopkins, in the reign of Queen Anne, with additions by Dr. Thomas. The notes on the Malvern windows have been printed in the Antiquities of the Cathedral Church of Worcester, and Malvern Priory, 8vo., 1728; Nash's Hist. of Worcestershire, ii. 129; and in the new edition of the Monasticon. Dr. Thomas gave a Latin version in his Antiquities of Malvern Priory.

- ↑ Leland, Coll. de rebus Britann. i. f. 62.

- ↑ "Una virgata terre in Baldeh, de feudo de Hanley, quam Hex Edwardus dedit." Carta R. Henr. I. A.D. 1127. In another charter of Henry I., cited in Pat. 50 Edw. III., per inspeximus, it is called "Baldehala," and in Plac. 12 Edw. II., "Badenhale."

- ↑ Nash, Hist. of Worcestershire, ii. 133.

- ↑ Antiqu. Prioratus majoris Malverne: descriptio ecclesiæ, p. 21.

- ↑ Carta Ant. L. F. C. xviii. 11, in the British Museum.

- ↑ Ecton gives in 1754, "Newland, St. Michael, Cap. to Malverne Magna. Wordsfield, Chapel to Malverne Magna, in ruins." The former is the little church on Newland Green, on the road from Malvern to Worcester.