Archaeological Journal/Volume 3/Illustrations of Domestic Customs during the Middle Ages. Ornamental Fruit-Trenchers inscribed with Posies

ILLUSTRATIONS OF DOMESTIC CUSTOMS DURING THE IMIDDLE AGES.

ORNAMENTAL FRUIT-TRENCHERS INSCRIBED WITH POSIES.

The usages of social life amongst our ancestors present a subject of interesting enquiry, appearing to deserve more careful consideration than it has hitherto received. The most minute details connected with pagan customs, and the illustration of domestic usages, costume, or the refinements of advancing civilisation amongst the Greeks and Romans, have been investigated with the utmost diligence, whilst the curious evidences relating to the private life of bygone times, in our own country, have been very imperfectly noticed. Those national monuments which display the constructive genius of our forefathers in their ecclesiastical, castellated, or domestic edifices, have for some time arrested the attention of numerous lovers of antiquity, and the smallest details of architectural ornament or arrangement have been examined with keen interest. Should the numerous scattered evidences which remain be regarded as devoid of interest, which may enable the antiquary to revive the stirring picture of daily life and social manners within those ancient walls, of which every feature has become now so familiar to us?

The investigation of the domestic habits of former times is a subject of much variety and extent, and the vestiges presented to us may frequently appear so trivial in their nature as to be unworthy of consideration. Amongst minor objects connected with festive usages, those now brought before the notice of our readers may possibly appear to be of that trivial character, and to have received already from antiquarians as full a share of attention as they can deserve. It does not appear, however, that any correct representation of the curiously ornamented "fruit-trenchers," in fashion during the sixteenth century, has hitherto been given, in illustration of various conjectures advanced regarding them; and I would hope that the examples, which I have been kindly permitted to submit to the readers of the Journal, may not prove devoid of interest; possibly, even that they may prove the means of drawing forth some further information.

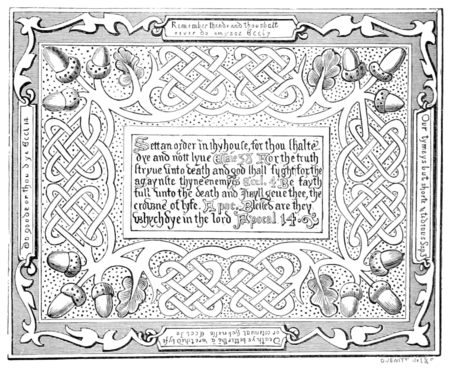

The only set of tablets, or trenchers, of this description, rectangular in form, hitherto noticed, are in the possession of Mrs. Bird, of Upton-on-Severn. They are twelve in number, formed of thin leaves, of some light-coloured wood, possibly that of the lime-tree, measuring about 534 inches by 412 inches, and enclosed in a wooden case formed like a book with clasps, the sides being decorated with an elegant arabesque design, imitating the patterns of impressed bindings, such as were found in the libraries of Grolier or Maioli. On removing a sliding piece which forms the upper margin of this little tome the tablets may be taken out. They are curiously painted and gilt, every one presenting a different design, and inscribed with verses from holy writ conveying some moral admonition. Each tablet relates to a distinct subject. These legends are enclosed in compartments, as shewn in the annexed representation, surrounded by various kinds of foliage and the old fashioned flowers of an English garden, the campion, honeysuckle, and gilliflower, each tablet being ornamented with a different flower. The trencher, of which a representation is given, bears the oak-leaf and acorns, and the texts inscribed upon it relate to the uncertainty of human life. Upon the others are found admonitions against covetonsness, hatred, malice, gluttony, profane swearing and evil speaking, with texts in which the virtues of benevolence, patience, chastity, forgiveness of injuries, and so forth, are inculcated.The specimen here given may shew the quaint arrangement of these inscriptions.

The following are the texts relating to inebriety, and it may deserve remark that, having been taken from a version of the Scriptures, previous to the subdivision into verses, the chapters only are indicated. In the centre, "Wo be vnto you that ryse vppe early to geue your selues to dronkenes, and set all your myndes so on drynckynge, that ye sytte swearynge therat vntyll yt be nighte. The Harpe, the Lute, the Tabour, the Drumslade, the Trumpet, the Shalme, and plentye of wyne, are at your feastes, but the worde of the lorde, do ye not beholde, neyther consydre ye the workes of hys handes. Esaie the Prophete î the 5. Chap." In the four compartments of the margin, "Take hede that your hart' be not ouerwhelmed wyth feastynge and dronkenship. Luk. 21. Thorowe glotonye many peryshe. Eccl. 35. Thorowe feastynge many haue dyed but he that eateth measurably p'longeth lyfe. Eccl. 37. Be no wyne bybber. Eccl. 31."

The sides thus ornamented were coated with a hard transparent varnish, and have suffered very slightly by use; the reverse, which probably was the side upon which the fruit or comfits were laid, is smooth and clean, without varnish or colour. These curious "fruit-trenchers" were found amongst a variety of old articles at Elmley castle, Worcestershire, about twenty years since; and they were presented to Mrs. Bird, by Mr. E. Woodward, of Pershore.

By the obliging permission of the lady amongst whose collections these singular tablets had thus been deposited, they were included in the assemblage of interesting objects of antiquity and art, exhibited at the Deanery during the meeting of the Institute at Winchester, September, 1845. The kindness of Mrs. Bird in this instance was the cause of bringing to light other sets of "fruit-trenchers." One of these, belonging to Jervoise Clarke Jervoise, Esq., of Idsworth Park, Hants, consisted of ten trenchers, of the more usual form of roundels, ornamented in precisely similar style to those already described; they measure 514 inches in diameter, and are enclosed in a box, which bears upon its cover the royal arms, France and England quarterly, surmounted by the imperial crown. The supporters of the scutcheon are the lion and the dragon, indicating that these roundels are of the times of Queen Elizabeth. On each is inscribed a rhyming stanza and Scripture texts, each relating, as those on the tablets already described, to some different subject of moral admonition. The following examples may suffice to shew the character of these quaint "posies."Under the symbol of a skull,

"Content yi selfe wth thyn estat

And sende noo poore wight from thy gate

For why this coũcell I ye giue

To learn to die and die to lyue

Set an order in yi liouse for yu shalt die & not lyue. Ecl. 3.

Thy goodes wel got by knowledge skile

Wil healpe yi hungrie bagges to fyll

But riches gayned by falsehoodes drift

Will run awaie as streame ful swift.

Though hungrie meales be put in pot

Yet conscience cleare keept wthout spot

Doth keepe ye corpes in quiet rest

Than hee that thousandes hathe in cchest.

With out faith yt is vnpossible to please God. Hebrew the. 11."

It must be admitted that these uncourtly rhymes seem ill deserving to be designated as "posies." They are of the same doggrel character as various others communicated from time to time to Mr. Urban, amongst which may be mentioned a roundel formerly in the possession of Ives, the historian of Burgh castle, and described by him as a trencher for cheese or sweetmeats. These roundels have, however, been considered by some antiquaries as intended to be used in some social game, like modern conversation cards: their proper use appears to be sufficiently proved by the chapter on "posies" in the "Art of English Poesie," published in 1589[1], which contains the following statement. "There be also another like epigrams that were sent usually for new yeare's gifts, or to be printed or put upon banketting dishes of sugar plate, or of March paines, &c., they were called Nenia or Apophoreta, and never contained above one verse, or two at the most, but the shorter the better. We call them poesies, and do paint them now-a-dayes upon the back sides of our fruit-trenchers of wood, or use them as devises in ringes and armes."

It was the usage in olden times to close the banquet with "confettes, sugar plate, fertes with other subtilties, with Ipo- crass," served to the guests as they stood at the board, after grace was said[2]. The period has not been stated at which the fashion of desserts and long sittings after the principal meal in the day became an established custom. It was, doubtless, at the time when that repast, which during the reign of Elizabeth had been at eleven before noon, amongst the higher classes in England, took the place of the supper, usually served at five, or between five and six, at that period[3]. The prolonged revelry, once known as the "reare supper," may have led to the custom of following up the dinner with a sumptuous dessert. Be this as it may, there can be little question that the concluding service of the social meal, composed, as Harrison, who wrote about the year 1579, informs us, of "fruit and conceits of all sorts," was dispensed upon the ornamental trenchers above described. It is not easy to fix the period at which their use commenced: in the "Doucean Museum" at Goodrich Court, there is a set of roundels, closely resembling those in the possession of Mr. Clarke Jervoise, which, as Sir Samuel Meyrick states in the Catalogue of that curious collection, appear, by the badge of the rose and pomegranate conjoined, to be of the early part of the reign of Henry VIII.[4] Possibly they may have been introduced with many foreign "conceits" and luxuries from France and Germany, during that reign. In the times of Elizabeth mention first occurs of fruit-dishes of any ornamental ware, the service of the table having previously been performed with dishes, platters, and saucers of pewter, and "treen" or wooden trenchers; or, in more stately establishments, with silver plate. Shakspeare makes mention of "China dishes[5]" but it is more probable that they were of the ornamental ware fabricated in Italy, and properly termed Maiolica, than of oriental porcelain. The first mention of "porselyn" in England occurs in 1587-8, when its rarity was so great, that a porringer and a cup of that costly ware were selected as new year's gifts presented to the queen by Burghley and Cecil[6]. Shortly after, mention is made by several writers of "earthen vessell painted; costly fruit-dishes of fine earth painted; fine dishes of earth painted, such as are brought from Venice[7]."

Those elegant Italian wares, which in France appear to have superseded the more homely appliances of the festive table, about the middle of the sixteenth century, were doubtless adopted at the tables of the higher classes in our own country, towards its close. The wooden fruit-trencher was not, however, wholly disused during the seventeenth century, and amongst sets of roundels which may be assigned to the reign of James I. or Charles I., those in the possession of Mr. Hailstone may be mentioned, exhibited in the museum formed during the meeting of the Institute at York. They were purchased in a broker's shop at Bradford, Yorkshire; in dimensions they resemble the trenchers of the reign of Elizabeth, already described; but their decoration is of a more ordinary character. On each tablet is pasted a line engraving, of coarse execution, and gaudily coloured, representing one of the Sibyls. Around the margin is inscribed a stanza. The following may serve as a specimen.

"The Phrygian Sibill named Cassandra.

God readie is to punishe mans mischance,

Ore swolne with sinne, hood-winckt with ignorance

Into the Virgins wombe to make all euen,

Hee comes from heauen to earlhe, to giue vs heauen."

ALBERT WAY.