Archaeological Journal/Volume 3/Notices of Ancient Ornaments, Vessels, and Appliances of Sacred Use, the Chalice

NOTICES OF ANCIENT ORNAMENTS, VESSELS,

AND APPLIANCES OF SACRED USE.

Amongst the numerous sacred vessels and objects connected with the rites and ceremonies of the Christian Church, those which were appropriated to the most solemn of religious ordinances, the consecration of the Holy Eucharist, must be regarded with special and reverential interest. They may claim attention, on account of the perfection or profuse variety of their decoration, bestowed by that unsparing liberality of former times in all occasions wherein veneration for the house of God, or the services of the Church, could be evinced. They present also the most choice examples of various decorative arts, of which such objects, preserved on account of their sacred character, now supply almost the only evidence, whilst the richest ornaments of personal and unhallowed use have been destroyed under the capricious influence of fashion. They are, however, still more interesting when regarded in connection with the successive changes in the discipline of the Church, or the modifications of ritual observance, in conformity with which, the forms of such hallowed accessories were at various times and in different countries modified or ordained. Thus it will be found that, in earlier times, whilst the communion of the faithful under both kinds was permitted, the chalice, termed ministralis, or communicalis, was of considerable capacity, and furnished not unfrequently with a handle on either side, (calix ansata,) so that it might be raised with greater ease and security. A curious representation of such a chalice occurs amongst the embroideries of the Imperial Dalmatic, of Byzantine workmanship, preserved at St. Peter's at Rome, as the "cappa di S. Leone III." (795—816,) but probably not more ancient than the eleventh or twelfth century[1]. It may likewise be seen in the missal of the abbey of St. Denis, now preserved in the Bibliothèque Royale, where the miraculous appearance of the Saviour, and administration of the Eucharist, to St. Denis are portrayed. This MS. is attributed to the eleventh century. Theophilus, who wrote his treatise about the same period, as it is supposed, gives, with detailed instructions for the fabrication of the greater and lesser chalice, a chapter on fashioning the auricula, or aures, of such vessels, a term by which the side-handles appear to be designated[2]. These large chalices furnished with handles were occasionally suspended in churches with coronæ and other ornaments, and are termed by Agnelli calices appensorii, they may be seen in the illuminations of the Bible of Charles le Chauve, and other MSS. In many cases the calices ansati appear to have been used as receptacles for wine, in place of the stoup or flagon of recent times; being ill suited, on account of their large dimensions, for the purpose of administration. A large chalice with two handles, which could not easily be raised by a man, was preserved in the treasury of Mayence cathedral[3].

The fashion of the chalice in primitive ages, was, probably, of the most simple kind. The silver chalice formerly exhibited to pilgrims at Jerusalem as the cup used by our Saviour at the last supper, was formed, as described by Bede, with two handles[4]; and although the antiquity of the tradition may be questionable, it is not improbable that in many instances the shape of the calix ansatus may have been assimilated to such a revered model. In later times a plain cup was used, somewhat more elevated in its proportions, fashioned with a knop, or pomellum, beneath the bowl, whereby it might be securely held; and it was occasionally inscribed or marked by some appropriate symbol[5]. Subsequently, the bowl was made of smaller proportions, the administration of the wine to the laity being forbidden; and, as a precaution against the risk of its being overturned, the foot was made very wide, with indentations, intended, according to De Vert, to keep the chalice steady, when it was laid to drain on the paten, after celebration, in accordance with an ancient usage[6]. The knop and foot were decorated in the most sumptuous manner, the bowl being usually quite plain; nielli, enamels, gems, and other precious objects were incrusted amongst the elaborately chased or graven ornaments of the lower parts of the chalice.

The apprehension that some portion of the sacred element might accidentally be spilled during administration, had previously caused the use of a pipe, (fistula, pipa, syphon, pugillaris, canna, or calamus;) the wine was thus drawn from the chalice by suction. This custom, long retained at Chuny, St. Denis, and other monasteries, as also at the coronation of the kings of France[7], is now only observed by the Pope. It is supposed to have been of high antiquity, and was not unknown in Britain, as appears by the inventory of vessels and vestments given to the church of Exeter by Bishop Leofric, (circa A.D. 1046,) amongst which were five silver chalices, and one "silfrene pipe," the Anglo-Saxon term whereby the fistula appears to be designated in a contemporary inventory[8]. Florence of Worcester likewise states that William Rufus, after his coronation, A.D. 1087, bestowed upon the chief churches in the realm precious gifts, "fistulas," sacred vessels and ornaments. This tube was occasionally fixed permanently in the chalice, according to the minute directions given by Theophilus[9]. The Greek Church had adopted the usage of dipping the bread in the wine, the administration being made with a spoon, (labida,) a practice supposed by some to have been not wholly unknown in the Western Church[10], but the spoon, or cochlear, frequently named with the chalice in inventories, appears to have been used in pouring the wine and water thereinto, and in some instances to have served as a strainer[11], properly called colatorium, for the formation of which detailed instructions are given by Theophilus.

To enumerate and explain the various artistic processes, which, according to the curious descriptions preserved in ancient documents, were employed to enrich these accessories of the service of the altar, would extend this notice beyond the limits suitable to the Archæological Journal. If any of our readers should desire to ascertain the customary and appropriate character of these decorations, the inventories of St. Paul's, London, A.D. 1295, of Lincoln cathedral, York Minster, and other churches, published by Dugdale, will be found to supply abundant information. With regard, however, to the material employed in the fabrication of chalices, it may be remarked, that the precious metals were always preferred, and that, in default thereof, chalices were formed of glass, horn, wood, or ordinary metals. Durandus, and other writers, have stated that the use of chalices of glass, to which allusion is made by Tertullian, was ordered by Pope Zephirinus, at the commencement of the third century, and that on account of their fragility Pope Urban shortly after prescribed that they should be formed of gold, silver, or, in poorer churches, of tin. About the same period the use of glass was forbidden by the council of Rheims, A.D. 226. It was not, however, wholly discontinued; the ancient sculpture in the cloisters of St. Stephen's, at Toulouse, represented St. Exuperius, who died early in the fifth century, attended by a deacon presenting to him a chalice; above was seen the following inscription, in wwhich that vessel is described as of glass:

"Sacramenta parat pia, pontificique ministrat.

Offert vas vitreum, vimineumque canistrum."

In a will, dated A.D. 837, are mentioned a chalice of ivory, another of cocoa-nut, mounted with gold and silver, and a third of glass; "calicem vitreum auro paratum[12]." The British council of Chalcuth, in the reign of Egbert, forbade the use of chalices or patens of horn, "quod de sanguine sunt[13];" and the canons enacted under Archbishop Dunstan, in the time of Edgar, enjoined that all chalices, wherein the housel is hallowed, be of molten work, (calic gegoten,) and that none be hallowed in a wooden vessel[14]. The Saxon laws of the Northumbrian priests imposed a fine upon those who should hallow housel in a wooden chalice[15], and the canons of Elfric repeat the injunction, that chalices of molten material, gold, silver, glass, (glæsen,) or tin, be used; not of horn, but especially not of wood[16]. Horn was rejected, because blood had entered into its composition[17]; wood, on account of its absorbent quality. Stone or marble were less objectionable[18], and precious gems were used, as in the case of the vessel of sardonyx, attributed to Abbot Suger, at St. Denis. The use of vessels of tin or pewter, in poorer churches, was not unfrequent: it had been sanctioned by the canons, but nevertheless was forbidden by the constitutions of Archbishop Wethershed, about A.D. 1229. Lyndwode observes that copper was objectionable, because it occasioned nausea, "quia provocat vomitum;" brass, as subject to oxidation, "quia contrahit rubiginem[19]."

These careful precautions evince the deep reverence with which, at all times, the sacred ordinance of the Eucharist was regarded, as further shewn by the solemn benediction of all vessels or appliances of the service of the altar, which may be found in ancient ceremonials, such especially as that of the Anglo- Saxon Church, preserved in the Public Library at Rouen[20].

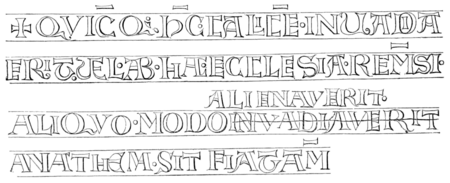

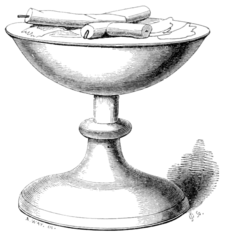

Several ancient chalices, highly interesting on account of their elaborate decoration, or traditions connected with them, exist in the treasuries of various churches, or in other depositories. One of the most remarkable, now preserved in the Cabinet of Antiquities in the Bibliothèque Royale, at Paris, is the "calice de St. Remi," formerly belonging to the cathedral of Rheims. This incomparable example of the skill of the twelfth century is of gold, incrusted with enamelled ornaments, gems, pearls, and filigree work of the most curious character. It measures, in height, 612 in., and the diameter of the cup is 5 in. and seven-eighths. This precious object is described in the account of the treasury of Rheims cathedral, and distinguished from the "calix ministerialis" of St. Remy, noticed by Flodoard[21]. The inscription which forms two lines around the foot of the chalice, denounces an anathema on any one who should abstract it from the church of Rheims. A singular instance is here to be noticed of the heedlessness of the artificer, who, having erroneously repeated the word INVADIAVERIT, instead of effacing the blunder, drew a single line through the letters, and corrected it by engraving the right word above the line. A similar reluctance to make any erasion appears frequently in medieval MSS. The fine preservation of this chalice is very remarkable, especially as it lay for some time in the river Seine, having been part of the plunder abstracted from the Cabinet of Medals, a few years since. At the time when the author was permitted (in 1839) to make the drawing from which the annexed representation has been executed, there were still adherent to the filigree small stones and sand from the bed of the Seine.

In the beautiful publications by Mr. Shaw, the Specimens of Ancient Church Plate, the Illustrations of the History of Medieval Art, by Du Sommerard, and other similar works, representations of many beautiful chalices may be found. Those which are preserved at Oxford, namely, one from St. Alban's Abbey, presented to Trinity College by Sir Thomas Pope, and the founder's chalice at Corpus Christi College[22], well deserve attention. Amongst the choice collections in Mr. Magniac's possession there is a beautiful specimen of Italian workmanship, of the fourteenth century, decorated with enamels, and inscribed ✠ ANDRƐA PƐTRUCI DƐ SƐNIS MƐ FƐCIT⋅ Mr. Shaw has given another, of similar character, bearing the name of another artificer of Sienna[23]; and Italian chalices, of great beauty, may be seen in the De Bruges, and other collections, at Paris. An interesting example of the form of the chalice in our own country, towards the close of the fifteenth century, is supplied by one in Lord Hatherton's possession, at Teddesley, discovered a few years since, concealed in the walls of the old Hall of Pillaton, near Penkridge. The prevalent fashion of this sacred vessel, at various periods, may be ascertained by numerous examples which have been found in the graves of ecclesiastics, as likewise by their sepulchral effigies, on which the chalice is frequently represented, held reverently between the hands, or deposited upon the breast.

The usage of depositing a chalice and paten with the corpse of a priest appears to have been very generally observed; and, although no established regulation may be found which prescribed the observance of this custom, it is in accordance with ancient evidences cited by Martene, in his treatise on Rites observed at the Obsequies of Ecclesiastics. Occasionally, not only the sacred vessels, but a portion of the Eucharist was placed upon the breast of the deceased, as on the occasion of the interment of St. Cuthbert, according to the relation of Bede. This usage had been adopted from very early times, although forbidden by several councils[24]. An ancient writer on ritual observances, cited by Martene, states that it was customary to place over the head of the corpse a sigillum of wax, fashioned in the form of a cross: that the bodies of persons who had received sacred orders ought to be interred in the vestments worn by them at ordination; and that on the breast of a priest ought to be placed a chalice, which, in default of such sacred vessel of pewter, should be of earthen-ware[25]. Numerous instances of the discovery of a chalice and paten in the grave of an ecclesiastic have been noticed; they have usually been formed of tin or pewter, but occasionally a chalice of more precious metal was deposited with the corpse, as in the stone coffin, supposed to contain the remains of Hugh de Byshbury, Rector of Byshbury in Staffordshire, t. Edw. III., wherein was found a small silver chalice, afterwards appropriated to the use of the church[26]. Several chalices are preserved at York, which have been at various times found in the graves of ecclesiastics, in the Minster: of a similar discovery in the coffin supposed to contain the remains of Henry of Worcester, abbot of Evesham, who died A.D. 1263, an interesting record has been preserved by Mr. Rudge[27], and many other examples might be cited.In forming a grave in Hereford cathedral, in 1836, a place of sepulture was brought to light, containing human remains, clothed in vestments which had been richly embroidered; at the right side lay a small chalice and paten of white metal, and on the paten were two pieces of wax taper, the wicks partly consumed, placed in the form of a cross. This singular circumstance seemed to indicate a practice, analogous, in some measure, to the deposit of the waxen sigillum, according to the ancient Custumal above mentioned, cited by Martene[28]. The chalice was placed in the hand of the deacon, as a kind of investiture, at his ordination, as represented in the curious subject from the legend of St. Guthlac, given in a former volume of this Journal[29]. The same, possibly, was in many instances placed between the hands of the defunct priest, whilst his corpse was exposed to view, previously to interment, and finally was deposited therewith. In default of such vessel a cup of earthen-ware was sometimes used, as we have been informed by Martene, and instances of the discovery of such fictile chalices have occurred, even in our own country. Dr. Milner relates that, near the West Gate, at Winchester, adjoining to the parish of St. Valery, there had anciently been a church and cemetery, wherein were found in graves two earthen chalices, such as were buried with priests[30]. It is, indeed, possible that these might have been small cressets, or funerary lamps, deposited in Christian sepulchres, according to ancient usage, as shewn by many curious examples.

Henry Denton, Higham Ferrers.

A. Apparel or Parura of the Amice.

A. Apparel or Parura of the Amice.

B. Stole.D. Chasuble or Chesible.

C. Maniple, or fanon.D. Alb, with apparel at the feet.

Sepulchral brasses afford many interesting illustrations of the form of the chalice, and of the usage of its deposit in the tomb of a priest. The effigies of priests, at North Mimms, Herts, and Wensley, Yorkshire, supply very richly decorated examples. Both of these are of the fourteenth century, and a fine specimen is given by Mr. Shaw, from the memorial of a chancellor of Noyon Cathedral, who died 1358[31]. Many other instances may readily be enumerated; most commonly the wafer is represented, placed over the chalice, and occasionally with rays radiating from it. The chalice is usually held between the hands, but sometimes it is placed upon the body, as in the figure of the priest at North Mimms, already noticed.

There is an incident in the history of our country, at a very interesting period, to which it may not be inappropriate to advert, in concluding these notices of the most sacred of the ornaments of churches. In the year 1193 the Emperor Henry had thrown Richard king of England into a dungeon in the Tyrol; one hundred thousand pounds of silver were demanded as ransom, a sum far beyond the exhausted resources of the captive monarch's exchequer, impoverished by the expenses of protracted warfare in a remote country. No ordinary means appeared available. In vain did his mother Alianore send into every part of the realm to levy from each subject according to his estate; a second and a third time did the measure prove insufficient to meet the pressing emergency: at length Richard resolved upon an extraordinary expedient—he wrote to his mother and the justiciaries, directing them to take the gold and silver in the churches of the realm, and to give a solemn pledge that full restitution should be made[32]. At such a moment of exigency none appear to have offered opposition; the chalice of each parish church was readily given towards the redemption of the lion-hearted King; the treasures of wealthier establishments were likewise rendered up to the commissioners, or an equivalent paid in money[33]; and the sum thus amassed at length sufficed for the king's liberation. When the light of heaven again shone upon the ransomed captive, and he found himself securely restored to his dominions, the solemn promise was not overlooked; restoration was made, and wherever he learned that, in the most remote country church the altar had been despoiled of its appropriate ornaments for his redemption, Richard forthwith dispensed to them chalices of silver, accounting it a personal reproach that the services of the church should, on his account, be conducted with any want of suitable solemnity[34].

- ↑ Boisserée, Dissertation published in the Annals of the Royal Academy of Bavaria. Didron, Annales Archéologiques, tom. i. p. 152.

- ↑ Diversarum artium schedula, ed. L'Escalopier, p. 155.

- ↑ It may be doubtful whether the antique vase of oriental agate, given to St. Denis by Charles III., was ever used as a chalice, the ornaments sculptured upon it being of a profane character, but the famous chalice of the Abbot Suger, formed of the same material, as likewise one of crystal, attributed to St. Denis himself, had handles. Felibien, plates iii. vi., p. 541. There were curious chalices with handles at St. Josse sur Mer, near Montreuil, and in other churches in France, noticed by De Vert, Cerem. de L'Egl. iv. 162.

- ↑ Beda, de locis Sanctis, c. 2. Adamnanus de locis sacris, lib. i. Baron. An. 34. Another chalice, formed of agate, supposed to have been used by the Saviour, was preserved at Valentia, in Spain.

- ↑ The chalice of St. Ludgerius, founder of the abbey of Verden, A.D. 796, was there preserved, and the Benedictines have given a representation of it. An inscription ran round both the edge of the bowl and the foot. Voyage Litt. ii. 234. Of somewhat similar form is the silver cup discovered at St. Austell, in Cornwall, with objects of Saxon date, and a coin of Burghred, king of Mercia, dethroned A.D. 874. It was subsequently used as a communion cup in a neighbouring parish church. Archæol. ix. pl. viii., and xi. pl. vii.

- ↑ The chalice was formerly laid on its side also at the commencement of the mass, See M. Didron's interesting dissertation on the tapestry at Montpezat, representing the mass of St. Martin. Annales Archæol., iii. 108.

- ↑ See the History of the Abbey of St. Denis, by Doublet, p. 334. Representations of the fistula are given by F. de Berlendis, Dissert. de Oblationibus, p. 148. Martene de Ant. Rit., lib. ii. c. 4.

- ↑ MS. Bibl. Bodl. Mon. Ang. i. 221.

- ↑ Edit.. L'Escalopier, pp. 177, 291. See also Lindanus, Panoplia Evang. p. 342. Voyage Litt. ii. p. 61.

- ↑ See Ducange, v. Sumptorium.

- ↑ Doublet, Hist. de S. Denis, p. 334. A golden chalice, paten, and spoon, are enumerated amongst the sumptuous ornaments of the chapel of Richard II. at Windsor, A.D. 1384. In a MS. inventory of the vessels at Bayeux cathedral, occur "un calice d'argent—avec une cuillère a servir l'eau." A.D. 1476.

- ↑ Testam. Everardi Comitis, ap. Miræum, i. 21. Macer describes an ancient chalice of glass, with two handles, seen by him in the possession of the papal almoner. Hierolexicon, v. Calix.

- ↑ Wilkins, i. 147, A.D. 785.

- ↑ Wilkins, i. 227. Ancient Laws and Instit., ii. 253.

- ↑ Ancient Laws and Instit., ii. 293.

- ↑ Laws and Inst., ii. 351. See also Elfric's Pastoral Epistle, ib. 385.

- ↑ Bartholinus describes an ancient chalice of horn, in his possession, anciently used in Norway. Medicina Danorum domestica.

- ↑ In the life of St. Theodore, ap. Surium, 22 April, it is related that where vessels of marble were used, he replaced them with silver.

- ↑ Lyndw. Provinc., pp. 9. 234.

- ↑ Mr. Rokewode considered this remarkable MS. as written late in the tenth century. See the Ordo for the benediction of the chalice, Archæol., xxv. p. 264.

- ↑ Gul. Marlot, Metrop. Rom. Hist., ii. 474. M. Didron has given a short notice of this remarkable chalice in the Annales Archéologiques, ii. 363, accompanied by a plate which exhibits various examples of its curious ornamentation.

- ↑ Shaw's Specimens of ancient furniture, pl. lxix. Specimens of ancient church plate (by the Rev. W. Lukis.) In the last publication are given representations of ancient chalices existing at Comb Pyne, Devon, and Leominster.

- ↑ Dresses and Decorations, by Henry Shaw.

- ↑ Martene, Eccl. Rit., lib. iii. c. xii. See Martene's observations, ib. § 10.

- ↑ "Sigillum cereum in modum crucis compactum, et aquam benedictam continens, super caput defuncti ponimus, &c. Clerici vero ordinati cum illis indumentis in quibus fuerunt ordinati debent et sepeliri, et sacerdos cum illis cum quibus assistit altari: super pectus vero sacerdotis debet poni calix, et loco sigilli, quidquid sit de oblata; quod si non habetur stanneus, saltem Samius, id est, fictilis." Anon. Turon. in MS. Speculo Eccl.

- ↑ Shaw's Hist. of Staffordshire, vol. ii. p. 178. Hugh de Byshbury, according to tradition, built the chancel, and was buried adjoining to the south wall, in the churchyard, where his effigy, much defaced, may still be seen. The chalice is no longer to be found amongst the church-plate at Byshbury. Another silver chalice was found in Exeter cathedral, in the grave supposed to contain the remains of Bishop Thomas de Bytton, who died A.D. 1306. Gent. Mag. 1763, p. 396.

- ↑ Archæologia, vol. xx. p. 566.

- ↑ Amongst many other instances of such discoveries may be noticed several chalices found at Chichester, one of which, of singular form, has been assigned to the twelfth century; several found on the site of Hyde Abbey, represented by Carter, in his Sculpture and Painting; also two discovered in the choir at Lich- field, and formerly in Green's Museum. Shaw's Hist. Staff., vol. i. pp. 256, 332.

- ↑ Archæol. Journal, vol. i. p. 286.

- ↑ Hist. of Winchester.

- ↑ Clutterbuck's Herts; Waller's Sepulchral Brasses; Shaw's Dresses and Decorations. See other examples in Cotman's Brasses of Norfolk and Suffolk.

- ↑ Hoveden, Script. post Bedam, 726, 733.

- ↑ Amongst the benefactors of St. Alban's Abbey is specially named Abbot Garin, who, being warmly attached to King Richard, redeemed the chalices of the Abbey at the price of 200 marks. Cott. MS. Nero D. VII.

- ↑ Brompton, 1256, 1258. Knyghton, 2408.