Archaeological Journal/Volume 9/The Collection of British Antiquities in the British Museum

Bronze objects found near the River Wandle.

Presented by Robert Mylne, Esq.

(Length of sword, 30 in.; spear-head, 26 in.; curved pin, 20 in.)

THE COLLECTION OF BRITISH ANTIQUITIES IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

During the past year one of the new rooms in the British Museum has been set apart for a collection of British Antiquities. It has occurred to me that some account of the state and prospects of the collection might not be uninteresting to the members of the Archaeological Institute, more especially as it is in a great measure owing to the influence of the Society and of its liberal Patron, the Duke of Northumberland, that such a collection has been placed at last on a proper footing. I shall therefore notice briefly the materials already in the museum, and give a somewhat longer account of the acquisitions made during the year.

These materials are not extensive, and have been gradually accumulated from various sources during a long period of years. The only large number of objects relating to England which were obtained at one time were contained in the collection of Sir Hans Sloane: few of them, however, of great importance. The collections of Mr. Towneley and Mr. Payne Knight included some objects of great beauty, found in Britain, valued, however, by these eminent collectors rather on account of their artistic merits than of their interest to the British archaeologist.

Among the antiquities which belong to those obscurer periods of our history, known as the stone and bronze periods, may be noticed a considerable collection of weapons, &c., in those materials, collected chiefly during the Ordnance Survey of Ireland; no less than three bronze celt-moulds, and the shied[1] and dagger-sheath found in the bed of the Isis. To Robert Mylne, Esq., we are indebted for an interesting group of objects discovered at the mouth of the river Wandle, in Surrey. The perfect state of these remains and their value in being found together and probably, therefore, of contemporary workmanship render them important specimens in a collection. The sword, (fig. 1) is thirty inches long; it is of the usual type, though more carefully finished off than any I have seen. The portion to which the hilt was attached is unfortunately broken off. The spear-head (fig. 2) is remarkably light and strong, it is very carefully worked, especially towards the point, combining a very sharp edge with considerable thickness, some portion of the original wood remains in the socket.

The length of the whole is 26 inches. The celt (fig. 3) of the form known to the antiquaries of the North as Palstaves has been cast and carefully hammered at the sides. The pin (fig. 4) is the most interesting object of the whole, the curved point as appears by other specimens, is purposely made. The bulging portion in the centre is pierced, probably to allow of a chain being attached to the pin for greater safety. The purpose to which this object was applied must have been to adorn the hair, or fasten the dress. Its length is 20 inches. The collection is very deficient in Celtic pottery, the most important object being the urn supposed to have contained the ashes of Bronwen the Fair, aunt to Caractacus, found on the banks of the Alaw, Anglesea.[2] The gold ornaments of this period include the Mold breastplate[3] and a considerable number of antiquities from Ireland.

The relics of the Roman occupation of Britain form the most considerable portion of the whole collection. Most of the varieties of pottery used by the Romans are to be found there. Among these should be noticed a considerable number of vessels, various in form and colour, discovered in excavations at the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich, and deposited in the Museum by the Board of Ordnance. Several urns were presented by the Right Hon, the Speaker, found in 1839, near the Reading-road bridge in the parish of Basingstoke. To Mr. Diamond we are indebted for the interesting collection of fragments found in the pits at Ewell,[4] and to Canon Rogers for the remarkable specimen of red ware, bearing an inscription in unknown characters, found in the Cathedral Close at Exeter.[5] Among the bronze objects are an Egyptian figure of Osiris Pethempamentes discovered in the Roman camp at Swanscombe, in Kent. The magnificent inlaid figure of a Roman general, discovered at Barking Hall, in Suffolk.[6] The tabulæ honestæ missionis found at Sydenham and Malpas,[7] The helmet from Tring,[8] and the mirror-case from Coddenham in Suffolk.[9] Mr. Lysons and Lord Selsey deposited in the Museum the greater part of the objects engraved by the former in his Reliquæ Britannico-Romanæ;[10] while with Mr. Towneley's collection came the antiquities from Ribchester.[11] The Roman silver plate includes the splendid objects found on the estate of Sir John Swinburne in Northumberland,[12] and the dish found at Mileham in Norfolk.[13] Several glass vessels require to be noticed, viz., those found at Hemel Hempstead,[14] Long Melford in Suffolk,[15] Harpenden in Hertfordshire,[16] and Southfleet in Kent.[17] The sarcophagi in which the two latter were found are also in the Museum. Among the gold ornaments are to be observed the curious collection found near the Roman wall,[18] and which formerly belonged to Mr. Brummell, as well as a fine armilla found at Wendover, in Buckinghamshire, presented by R. C. Fox, Esq.[19]

The Museum is not rich in Saxon antiquities. It possesses, however, two interesting collections which though not apparently the work of the Saxon invaders, still must be referred to the same period, viz.: the remains found at Polden Hill in Somersetshire,[20] and those from Stanwick, Yorkshire, presented by the Duke of Northumberland.[21] They consist chiefly of ornaments for men and horses. To the same period seem to belong the massive armillæ found at Drummond Castle, Perthshire, presented to the collection by Lord Willoughby d'Eresby.[22] Of Saxon relics, properly so called, the Hexham bucket,[23] Ethelwolf's ring, and the ornament found at Bacton in Norfolk[24] and presented by Miss Gurney, are the most important.

The mediæval objects which belong to this country have not been separated from those of foreign origin, nor till the latter become more numerous does there seem any necessity to do so. In the middle ages art was far more universal than at an earlier period, and the constant intercourse between various countries diminished to a certain extent any wide differences in workmanship. Among the objects found in England I must mention the chessmen found in the Isle of Lewis,[25] the two state swords of the Earldom of Chester, and some paintings from St. Stephen's Chapel, Westminster. There are likewise several ornamented paving tiles, including some very curious ones from Castle Acre. The English Porcelain manufactures have likewise their representatives. Two large vases made by Mr. Spremont at Chelsea, in 1762, were presented in the following year, and must have been nearly the last productions of that manufactory. There is likewise a bowl, the only authenticated specimen of the extinct manufactory at Bow.[26]

It now remains for us to notice the acquisitions made during the past year, which include several objects of importance. The numerous donations testify to the interest which is felt in a collection of national antiquities.

The greater part of the earlier antiquities which have been acquired were found in Wales. The Rev. J. M. Traherne has contributed one stone and three bronze celts, all found in Glamorganshire. From Lord Willoughby d'Eresby we have received a bronze sword and dagger discovered in cutting peat on his lordship's estates at Dolwyddelan, Caernarvonshire. A stone disk has been presented by Mr. Stokes, found in a ploughed field at Haverford West, South Wales. This is one of those curious objects which have been frequently found in England, but regarding which various opinions have been expressed. By some it has been conjectured to be the verticillus of a spindle, from its similarity to such objects found with Roman remains; by others a bead or a button. The last opinion seems not unlikely, as very similar objects have been found in Mexico, which have certainly been used as buttons. The present specimen has evidently had a cord passed through it, as the edges of the hole in the centre are much worn by friction. An important addition has been made to the collection of Celtic pottery by the Hon. W. O. Stanley, who has deposited in the Museum the curious urns found in a tumulus at Porth Dafarch, Anglesea. They have been fully noticed in a previous volume of the Journal[27] Another urn of unusual form has been presented to the Museum by Mr. Tomkins. It was found about twenty years ago in the centre of one of a group of seven barrows on a farm in the Parish of Broughton, Hampshire, and contained ashes. The urn is remarkable for two auricular projections on the prominent ridge of its exterior; the material is a coarse clay, slightly baked.

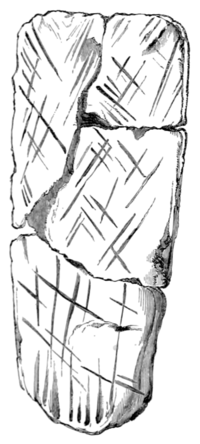

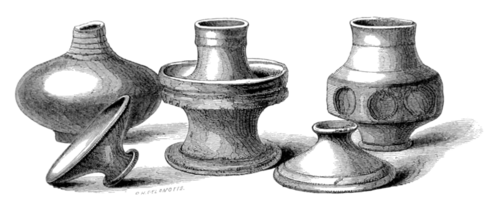

Among the Roman remains must be especially mentioned a stone sarcophagus presented by Henry Long, Esq. It is formed out of the malm-rock (lower chalk) and is a singular instance of so large a mass of that rock. It consists of a stone cist and cover, represented in the accompanying engraving; the cover is broken in several places, and is indented with rude scorings which are probably the marks of the ploughshare. It was found several years ago at a farm called Wheatleys, in the parish of Binstead, Hampshire, a little to the south of the Holt forest. It contained when found a skeleton and several small terra cotta vessels, six of which have been preserved. The three principal ones are black, the others which appear to have been used as covers, are of a light red. The spot where the discovery was made is a knoll on the verge of the malm escarpment, overlooking the valley of Kingsley and the forest of Woolmer. The Duchess of Grafton has presented the fragments found in the Sepulchral Cist, containing fictile vessels, found at Binstead Hampshire.

Presented to the British Museum, by Henry Long, Esq.

Of objects of Saxon times, I must allude to Mr. Deck's interesting situla and other relics, found at Streetway Hill, already published in the Journal,[32] and the curious gold earrings found at Soberton in Hampshire, with coins of Edward the Confessor.[33] The beautiful fibula found at Abingdon in Berkshire, and exhibited at Bristol by the President of Trinity, has, I am happy to say, been secured through his means for the National Collection.[34] To the Rev. E. Jarvis we are indebted for the very curious collection of ornaments found in a barrow at Caenby in Lincolnshire.[35]

Among the mediæval objects relating to England must be mentioned the brass pyx found at Exning in Suffolk,[36] and two pitchers of Flemish stoneware, one bearing the arms of Elizabeth, and the date 1594; the other the arms of England and the year 1607. Among the matrices of seals which have been added, are three brass ones, of considerable interest; the seal of John Holland, Earl of Huntingdon, as Admiral of England,[37] that of the town of Droitwich, and the seal of the Alnager of Wiltshire.[38]

Mediæval antiquities have not been neglected; a fine collection of twenty-one Majolica plates, has been purchased, painted by Maestro Giorgio, the best known master of the manufactory of Gubbio, as "well as several enamels of the earlier and later schools of Limoges. Several specimens of Venetian and German glass have been presented by Felix Slade, Esq.

Two large collections of foreign antiquities have been purchased during the last year, by the Trustees of the Museum, which are of considerable importance to the English archaeologist. The first of these is the very extensive collection of Celtic and Roman-Colonial Antiquities formed by M. Commarmond, of Lyons; a collection well worthy of examination, from the great similiarity of many of the objects in it, to those found in this country. The other collection is that formed by Professor Bähr, of Dresden, consisting of a vast quantity of bronze ornaments, and iron weapons and implements discovered by him in the graves of the Livonians. From the coins found with them, the greater part of these relics appear to belong to the tenth and eleventh centuries: they are closely allied with antiquities found in Denmark, but present many characteristic differences.[39] Both these collections are of great value from their having been made by two eminent archaeologists, who have watched the finding of the various objects and have recorded the parculars of their discovery.

It is scarcely necessary for me to call the attention of members of the Archaeological Institute to the value of a museum of national antiquities. We have all felt the want of it too much. For till such a collection is formed—till a large mass of antiquities has been been brought together from various parts of England and properly arranged, it will be impossible to make great advances in the study of our early antiquities. Local museums are institutions of great value, as they rescue from destruction many relics which would otherwise be lost, and they encourage a local feeling of reverence for the memorials of the past Still their claims are very inferior to those of a national collection. Objects of great importance to the archaeologist often He buried in these far distant receptacles, affording him facts of the highest value as links in a great chain, but in their isolation perfectly useless.

It is to the members of societies like our own, to the great lords of manors, the parish clergymen and country antiquaries that we must look for assistance. The value of objects is frequently lost when they pass through a dealer's hands: their authenticity is destroyed and their history mutilated, or they acquire a pedigree which only misleads the unwary archaeologist. I trust that the assistance we seek will be cheerfully given, more especially as we seek it not for ourselves, but from a wish to form for this nation a collection worthy of it, which shall teach all what manner of men their ancestors were. AUGUSTUS W. FRANKS.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxvii. p. 298.

- ↑ Archaeological Jour., vol. vi., p. 238.

- ↑ Monumenta Vetusta, vol. v.

- ↑ Archæologia.

- ↑ Journal of Brit. Arch. Ass., vol. iv., p. 20.

- ↑ Monumenta Vetusta, vol. iv., Pl. 11—15.

- ↑ Lysons' Reliquiæ Britannico-Romanæ.

- ↑ Monumenta Vetusta, vol. v.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxvii., p. 359.

- ↑ Vol. ii., pl. 34—42.

- ↑ Monumenta Vetusta, vol. iv., pl. 1—4.

- ↑ Archæologia, xv., p. 393.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxix., p. 389.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxvii., p. 434.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxiii., p. 394.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxiv., p. 349.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxv., p. 10.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., vol. viii., p. 35.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., vol. viii., p. 48.

- ↑ Archæologia, xiv., p. 90.

- ↑ Trans. of Arch. Inst. at York, p. 36.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxviii., p. 435.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxv., p. 279.

- ↑ Trans. of Norwich Society, vol. i.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxiv., p. 203.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., vol. viii., p. 204.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., Vol. vi., p. 226.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., vol. vii., p. 172.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., vol. viii., p. 205.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., vol. iv., p. 355.

- ↑ Archæologia, xxix., p. 7.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., vol. viii., p. 172. I should mention that we are indebted to the Hon. Richard Neville for several of the missing fragments of the bucket.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., vol. viii., p. 100.

- ↑ This fibula is similar to, but more perfect than, the one engraved in Arch. Jour., vol. iv., p. 252, which was found about the same place.

- ↑ Arch. Jour., vol. vii., p. 36.

- ↑ Vide Proceedings of the Bury Arch. Soc. This pyx was exhibited at the mediæval exhibition in 1850. The National Collection owes this acquisition to the Rev. A. Sharp, of Chippenham.

- ↑ Archæologia, xviii., p. 434.

- ↑ Archæologia, viii., p. 450, where it is wrongly described as of lead.

- ↑ They are fully described and engraved in Dr. Bähr's work, Die Gräber der Liven. Dresden, 1850.