STITCHES AND MECHANISM

AS a guiding classification of methods of embroidery considered from the technical point of view, I have set down the following heads:—

(a) Embroidery of materials in frames.

(b) Embroidery of materials held in the hand.

(c) Positions of the needle in making stitches.

(d) Varieties of stitches.

(e) Effects of stitches in relation to materials into which they are worked.

(f) Methods of stitching different materials together.

(g) Embroidery in relief.

(h) Embroidery on open grounds like net, etc.

(i) Drawn thread work; needlepoint lace.

(j) Embroidery allied to tapestry weaving.

In the first place, I define embroidery as the ornamental enrichment by needlework of a given material. Such material is usually a closely-woven stuff; but skins of animals, leather, etc., also serve as foundations for embroidery, and so do nets.

(a) Materials to be embroidered may be either stretched out in a frame, or held loosely (b) in the hand. Experience decides when either way is the better. For embroidery upon nets, frames are indispensable. The use of frames is also necessary when a particular aim of the embroiderer is to secure an even tension of stitch throughout his work. There are various frames, some large and standing on trestles; in these many feet of material can be stretched out. Then there are small handy frames in which a square foot or two of material is stretched; and again there are smaller frames, usually circular, in which a few inches of materials of delicate texture, like muslin and cambric, may be stretched.

Oriental embroiderers, like those of China, Japan, Persia, and India, are great users of frames for their work.

(c) Stitches having peculiar or individual characteristics are comparatively few. Almost all are in use for plain needlework. It is through the employment of them to render or express ornament or pattern that they become embroidery stitches. Some embroiderers and some schools of embroidery contend that the number of embroidery stitches is almost infinite. This, however, is probably one of the myths of the craft. To begin with, there are barely more than two different positions in which the needle is held for making a stitch—one when the needle is passed more or less horizontally through the material, the other when the needle is worked more or less vertically. In respect of the first-named way, the point of the needle enters the material usually in two places, and one pull takes the embroidery thread into the material more or less horizontally, or along or behind its surface (Fig. 1). In the second, the needle is passed upwards from beneath the material, pulled right through it, and then returned downwards, so that there are two pulls instead of one to complete a single stitch.

A hooked or crochet needle with a handle is held more or less vertically for working a chain stitch upon the surface of a material stretched in a frame, but this is a method of embroidery involving the use of an implement distinct from that done with the ordinary and freely-plied needle. Still, including this last-named method, which comes into the class of embroidery done with the needle in a more or less vertical position, we do not get more than two distinctive positions for holding the embroidery needle.

(d) Varieties of stitches may be classified under two sections: one of stitches in which the thread is looped, as in chain stitch, knotted stitches, and button-hole stitch; the other of stitches in which the thread is not looped, but lies flatly, as in short and long stitches—crewel or feather stitches as they are sometimes called,—darning stitches, tent and cross stitches, and satin stitch.

Almost all of these stitches produce different sorts of surface or texture in the embroidery done with them. Chain stitches, for instance, give a broken or granular-looking surface (Fig 2). This effect in surface is more strongly marked when knotted stitches are used. Satin stitches give a flat surface (Fig. 3), and are generally used for embroidery or details which are to be of an even tint of colour.

Crewel or long and short stitches combined (Fig. 4) give a slightly less even texture than satin stitches. Crewel stitch is specially adapted to the rendering of coloured surfaces of work in which different tints are to modulate into one another.

(e) The effects of stitches in relation to the materials into which they are worked can be considered under two broadly-marked divisions. The one is in regard to embroidery which is to produce an effect on one side only of a material; the other to embroidery which shall produce similar effects equally on both the back and front of the material. A darning and a satin stitch may be worked so that the embroidery has almost the same effect on both sides of the material. Chain stitch and crewel stitch can only be used with regard to effect on one side of a material.

(f) But these suggestions for a simple classification of embroidery do not by any means apply to many methods of so-called embroidery, the effects of which depend upon something more than stitches. In these other methods, cutting materials into shapes, stitching materials together, or on to one another, and drawing certain threads out of a woven material and then working over the undrawn threads, are involved. Applied or appliqué work is generally used in connection with ornament of bold forms. The larger and principal forms are cut out of one material and then stitched down to another—the junctures of the edges of the cut-out forms being usually concealed and the shapes of the forms emphasised by cord stitched along them. Patchwork depends for successful effect upon skill in cutting out the several pieces which are to be stitched together. Patchwork is a sort of mosaic work in textile materials; and, far beyond the homely patchwork quilt of country cottages, patchwork lends itself to the production of ingenious counterchanges of form and colour in complex patterns. These methods of appliqué and patchwork are peculiarly adapted to ornamental needlework which is to lie, or hang, stretched out flatly, and are not suited therefore to work in which is involved a calculated beauty of effect from folds.

(g) There are two or three classes of embroidery in relief which are not well adapted to embroideries on lissome materials in which folds are to be considered. Quilting is one of these classes. It may be artistically employed for rendering low-relief ornament, by means of a stout cord or padding placed between two bits of stuff, which are then ornamentally stitched together so that the cord or padding may fill out and give slight relief to the ornamental portions defined by and enclosed between the lines of stitching. There is also padded embroidery or work consisting of a number of details separately wrought in relief over padding of hanks of thread, wadding, and such like. Effects of high relief are obtainable by this method.

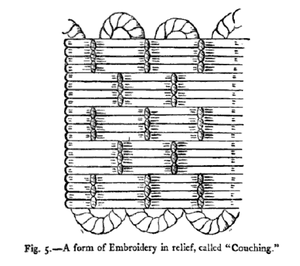

Another class, but of lower relief embroidery, is couching (Fig. 5), in which cords and gimps are laid side by side, in groups, upon the face of a material, and then stitched down to it. Various effects can be obtained in this method. The colour of the thread used to stitch the cords or gimp down may be different from that of the cords or gimp, and the stitches may of course be so taken as to produce small powdered or diaper patterns over the face of the groups of cords or gimp. Gold cords are often used in this class of work, which is peculiarly identified with ecclesiastical embroideries of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as also with Japanese work of later date.

(h) The embroidery and work hitherto alluded to has been such as requires a foundation of a closely woven nature, like linen, cloth, silk, and velvet. But there are varieties of embroidery done upon netted or meshed grounds. And on to these open grounds, embroidery in darning and chain stitches can be wrought. For the most part the embroideries upon open or meshed grounds have a lace-like appearance. In lace, the contrast between close work and open, or partially open, spaces about it plays an important part. The methods of making lace by the needle, or by bobbins on a cushion, are totally distinct from the methods of making lace-like embroideries upon net.

(i) Akin to lace and embroideries upon net is embroidery in which much of its special effect is obtained by the withdrawal of threads from the material, and then either whipping or overcasting in button-hole stitches the undrawn threads. The Persians and embroiderers in the Grecian Archipelago have excelled in such work, producing wondrously delicate textile grills of ingenious geometric patterns. In this drawn thread work, as it is called, we often meet with the employment of button-hole stitching, which is an important stitch in making needlepoint lace (Fig. 6).

(j) We also meet with the use of a weaving stitch resembling in effect, on a small scale, willow weaving for hurdles. This weaving stitch, and the method of compacting together the threads made with it, are closely allied to that special method of weaving known as tapestry weaving. Some of the earliest specimens of tapestry weaving consist of ornamental borders, bands, and panels, which were inwoven into tunics and cloaks worn by Greeks and Romans from the fourth century before Christ, up to the eighth or ninth after Christ. The scale of the work in these is so small, as compared with that of large tapestry wall-hangings of the fifteenth century, that the method may be regarded as being related more to drawn thread embroidery than to weaving into an extensive field of warp threads.

A sketch of the different employments of the foregoing methods of embroidery is not to be included in this paper. The universality of embroidery from the earliest of historic times is attested by evidences of its practice amongst primitive tribes throughout the world. Fragments of stitched materials or undoubted indications of them have been found in the remains of early American Indians, and in the cave dwellings of men who lived thousands of years before the period of historic Egyptians and Assyrians. Of Greek short and long stitch, and chain stitch and appliqué embroidery, there are specimens of the third or fourth century B.C. preserved in the Hermitage at St. Petersburg. Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans were skilful in the use of tapestry weaving stitches. Dainty embroidery, with delicate silken threads, was practised by the Chinese long before similar work was done in the countries west of Persia, or in countries which came within the Byzantine Empire. In the early days of that Empire, the Emperor Theodosius I. framed rules respecting the importation of silk, and made regulations for the labour employed in the gynæcea, the public weaving and embroidering rooms of that period, the development and organisation of which are traceable to the apartments allotted in private houses to the sempstresses and embroideresses who formed part of the well-to-do households of early classic times.

Alan S. Cole.