Canadian Alpine Journal/Volume 1/Number 2/The First Ascent of Mt. Garibaldi

On the extreme west of the Rocky Mountains system, hard by the waters of the North Pacific, is a mountain range little known beyond its own horizon. Its highest peaks do not compare in altitude with the giants of the Selkirks and Rockies, rising above valleys already at a considerable elevation, but they have the same alpine features of rock and glacier and snow, while their ascent involves climbing almost from the level of the sea. Moreover, they possess an added feature of beauty impossible to the ranges lying further east, their seaward slopes being indented with numerous fiords which find their way often into the very heart of the range.

The peak of greatest height is Mt. Garibaldi—known locally as "Old Baldi"—which stands at the head of Howe Sound, some thirty miles in from the Gulf of Georgia. Every dweller in the lovely Valley of the Squamish, which this mountain overlooks, is as proud of him as he is proud of his country; yet, except to these good people, he is all but a myth. Years ago a party attempted the ascent, but failed; and it looked, as time went on, as if Old Baldi were to crumble away in peace. But in that party were some who were "baffled to fight better," and this is why one stormy night, early in August, 1907, an adventurous group found themselves about a roaring fire in an old log house in the Squamish Valley, forty miles by water from Vancouver.

At six o'clock the next morning under a clear sky, we set out for the coveted summit, following the Tsee-Ki whose source is in Garibaldi's glaciers. At first the travelling was easy, for the rise was gradual and the country open; and in a few hours we were in the foothills, with the Tsee-Ki's milky waters boiling through canyons, and our mountain looming ever higher and more forbidding. By noon we reached a place where the way by the stream was barred and we were obliged to begin the ascent by a ridge on the left. And now our toils commenced. For 1,000 feet we had some very awkward rock-work made risky by loose fragments; and beyond this, a laborious grind of 5,000 feet up a wooded slope at an angle of 45 degrees. For hours we toiled up that interminable mountain-side with never a glimpse of a view to encourage us; until at last, when quite near the summit of the ridge, we "played out." We had been travelling for twelve hours. Camp was made in an open glade carpeted with heather, and with plenty of wood and pure water, we were soon comfortable for the night.

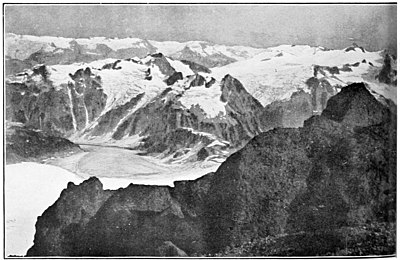

Early next morning we broke camp and continued the work of the previous day with keen anticipation. In a short while we were rewarded by our first panorama, for all at once we stepped on open ground and, looking back, beheld the whole Squamish Valley lying six thousand feet beneath us with its roads, rivers and farms showing as depicted upon a living map. Beyond lay Howe Sound stretching away to the open sea, and in the far distance Vancouver Island. We were feasting upon this scene when a shout from our amateur guides hurried us on. Almost before we knew what had happened, we found ourselves on the first crest with Garibaldi beyond in full view, and quite close. Towering heavenwards in one magnificent mass of rock, his precipices crowned with hanging glaciers, and all his upper heights wrapt in a mantle of fresh snow, he seemed some terrible monarch of the skies not to be approached by man. A rising ridge in the form of a crescent connected our present point with the glaciers behind the mountain. A steep descent of some three hundred feet brought us to its crest and along it we took our way. The whole ridge was clothed with fresh green grasses and blossoming heather, through which flowed here and there silvery streamlets of purest crystal. Clusters of trees were scattered about in reckless order, and gorgeous flowers in wild profusion made fragrant the air. In Indian file we moved along, ever on our right the mountain, and far below on the left the Squamish Valley and the ice-clad range beyond. Once a deer went bounding past with swift graceful motion, and then some fleecy clouds floated by. A few hours brought us to a commanding knoll, and here at timber-line we pitched camp in a group of dwarfed balsams. We now had a view behind Garibaldi of a vast sea of unknown mountains, glaciers and lakes.

After a somewhat uncanny night we awoke to find ourselves enveloped in clouds, so dense that our knoll seemed a little island in mid-ocean. All morning was spent in camp in that heavy, silent fog, but in the afternoon two of us set off with one of our guides for the base of the peak. It took two hours to get to it, steadily tramping up slopes of shale and snow in the thick fog. And then we reached a point where there was no sign of vegetation, and from whence we beheld the wildest scene of the trip. We stood on the top of a huge mass of rock, on one side was a precipice vanishing below in clouds, and on the other a very steep slope of trap rock, up which the clouds were surging from out the Tsee-Ki canyons. Within a stone's throw on the left darkly loomed the red walls of the dome of Garibaldi, and from a glacier at its base rushed a noisy little streamlet, the very head of the Tsee-Ki, which we had followed for twenty-five miles.

Early next morning the whole party set out to make an attempt at the ascent; but when we reached the snow-field below the peak, silent, desolate and trackless, the party would go no further. The fog gathered thickly and it was snowing; so, dejected, we returned to camp. Now happened what nearly ruined the whole expedition. Four of the party wanted to go home, and one of the leaders was willing, but the other bitterly opposed to it. The fate of that virgin peak hung in the balance. It was settled by the "youngster" of the party stepping alongside the "foolish" guide, as he was rated, and with him swearing to retreat not one step till more than mere clouds and snow flurries barred the way to the summit. It had been "do or die" sitting before a cosy hearth in town, so now the only way home was the Spartan one: with your shield or on it!

At sundown the wind veered to the north and in a few hours there was not a vestige of a cloud in the sky. Now we had cold to contend with, for an icy wind blew from the glaciers behind Garibaldi, and our supply of wood was ended. The break of dawn on the twelfth was the scene of a lifetime. All hands were up early and, just as the sun was tipping the surrounding peaks and tinting glacier after glacier, we set off for the third time up that mountain ridge. The peak showed clear but was clad with new snow and looked anything but easy. In a couple of hours we reached the base and here roped, with the two men of the former expedition as guides. Then we stepped out upon the glacier at an altitude of about eight thousand feet, and began to circle the peak—a pyramid rising two thousand feet—by the north. For an hour we walked steadily over new frozen snow of dazzling whiteness, constantly encountering ugly crevasses, the peak on our right, a wall of unscaleable precipices overhung by a glacier. For another hour we hurried on, gradually rising, the silence of those dismal wastes broken only by the sound of an alpenstock biting the frozen snow. Once the whole place was shaken by an avalanche which came thundering down the precipice on our flank. At eleven o'clock we reached the nine-thousand foot level where began the final struggle.

THE SUMMIT OF MT. GARIBALDI

LOOKING EAST FROM THE SUMMIT

In a kind of trance we at last crawled up a ridge of soft clean snow, and found ourselves standing on a flat, bare rock, with only the four winds about us and the heavens above us. One of our young guides planted a Union Jack; and we realized that a virgin peak was conquered—Garibaldi.

The view from that point ten thousand feet above the sea must be left to the imagination of those who have been in like places. A cairn was built, and then we hurriedly roped, for there were only four hours till nightfall and it had taken eight to make the ascent. Clouds were whirling about us now, and a storm was evidently coming on.

How we made the nerve-racking descent of that arête, and how once the front of our line went into one of those crevasses and was rescued, cannot be related here. Let it suffice that after a mad race with night and fog over the glaciers, we returned to camp, exhausted. One more night, and the worst, was spent in that desert spot, for all the elements seemed running riot, and our firewood was used up. In the morning we bade farewell to our never-to-be-forgotten camp, and set off home by the route we had come. Observation Point was reached, and then began the long tedious descent to the Tsee-Ki canyons. It rained in torrents, we lost our way and got entangled in a maze of cliffs. Several of these we overcame by sliding down our ropes, finally reaching the Tsee-Ki; and at 5 o'clock we stood on the Squamish road and were soon safe in our log house again.

Wednesday, the eighth day out, broke as clear and bright as ever a day seen by man, and we set off early down the country road on a farm wagon. Quietly we drove through that lovely valley, among its farms with their peaceful green lands and happy faces; above, the blue sky with a fringe of snow peaks.

Ten miles brought us to the sea where the little steamer "Britannia" waited. Then we bade farewell to Squamish and her "White-headed Baldi," and were homeward-bound.

The next four hours were spent steaming down that grand old fiord, Howe Sound, and at sunset we entered Vancouver harbor.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1929.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1927, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 96 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse

![]()

This work is in the public domain in Canada because it originates from Canada and one of the following statements is true:

- The author died over 70 years ago (before 1954) and the work was published more than 50 years ago (before 1974).

- The author died before 1972, meaning that copyright on that author's works expired before the Canadian copyright term was extended non-retroactively from 50 to 70 years on 30 December 2022.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1927, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 96 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse