Character of Renaissance Architecture/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III

CHURCH ARCHITECTURE OF THE FLORENTINE RENAISSANCE

No other work by Brunelleschi is comparable in merit to the great dome of the cathedral. None of his other opportunities were such as to call forth his best powers, which appear

Fig. 10.—Plan of the chapel of the Pazzi.

to have required great magnitude to bring them into full play. In his other works the influence of his Roman studies is more manifest, and his own genius is less apparent. In these other works he revives the use of the orders, and employs them in modes which for incongruity surpass anything that imperial Roman taste had devised.

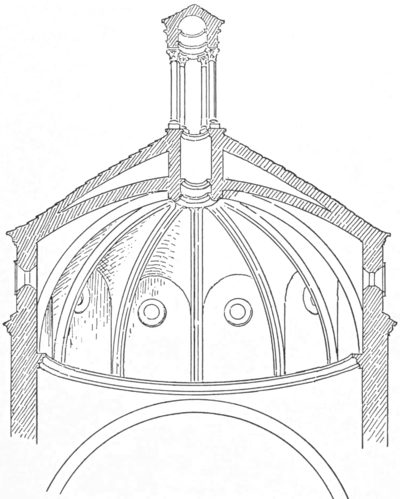

Fig. 11.—Section of vault of the Pazzi chapel.

The first of these works is the small chapel of the Pazzi in the cloister of Santa Croce. It is a simple rectangle on plan (Fig. 10), with a square sanctuary on the short axis, and a porch across the front. The central area is covered with a circular vault which by most writers is called a dome, but it is not a dome; it is a vault of essentially Gothic form, like two early Gothic apse vaults joined together (Fig. 11). It rests on pendentives, and is enclosed by a cylindrical drum, which forms an effective, though not a logical, abutment to its thrusts, and is covered with a low-pitched roof of masonry having a slightly curved outline. Whether this external covering is connected with the vaulting in any way above where it parts from the crowns of the vault cells it is impossible to discover, because there is no way of access to the open space between the two parts. Through a small opening in the outer shell, near its crown, the hand may be thrust into the void, but nothing can

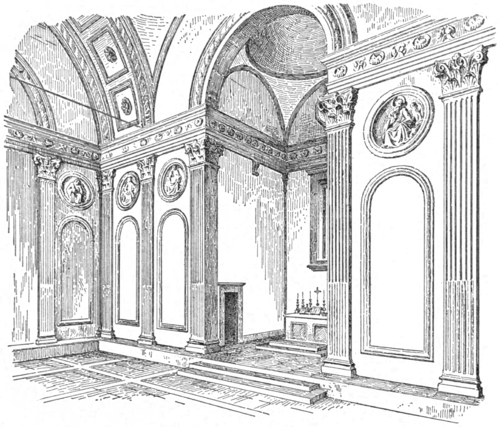

Fig. 12.—Interior of the Pazzi chapel.

be reached. It is a curious form of double vault, and differs fundamentally from the great double dome of the cathedral. The scheme as a whole is structurally inconsistent; for while the inner vault has the concentrated thrusts of Gothic construction, these thrusts are met by the enclosing drum, and not by the isolated abutments that the vault logically calls for. The sanctuary has a small hemispherical dome on pendentives, and the portico is covered with a barrel vault bisected by another small dome on pendentives. The architectural treatment of the interior (Fig. 12) exhibits a wide departure from that of any previous type of design. The form of the building is mediæval, being, with exception of the central vault, essentially Byzantine,[1] but the details are classic Roman, and consist of a shallow order of fluted Corinthian pilasters with the entablature at the level of the vaulting imposts. In such a building, however, and used in this way, a classic order is out of place; for an order is a structural system designed for structural use, but the order here has no more structural function than if it were merely painted on the walls. It is used, of course, with a purely ornamental motive, but as ornament it is inappropriate. A proper ornamental treatment of such an interior would be either by marble incrusting, mosaic, or fresco, or else by pilaster strips, or colonnettes, and blind arches, which would break the monotony of the broad wall surfaces without suggesting an architectural system foreign to the character of the building. Such arcading would have an appropriate structural suggestiveness, if not an actual structural use; but a classic order is unsuitable for a building of mediæval character. The mediæval pilaster strip and blind arcade were designed for this use, and they have the further advantage that their proportions may be indefinitely varied to meet varied needs, as the proportions of the classic orders may not. But in their lack of a true sense of structural expression, and in their eagerness to revive the use of classic forms, the designers of the Renaissance failed to consider these things.

A particularly awkward result of this improper use of an order is that the entablature passes through the arch imposts, making an irrational structural combination. This scheme was, however, extensively followed in the subsequent architecture of the Renaissance, but it is a barbarism for which no authority can, I believe, be found in ancient Roman design.[2] The nearest approach to it in Roman art is the entablature block resting on the capital (as in the great hall of the Baths of Caracalla), which was a blundering device of the later Roman architects. The complete entablature running through the impost, as in the chapel of the Pazzi, sometimes, indeed, occurs in the early churches of Rome and elsewhere,[3] as a result of unsettled conditions of design, while the architects were struggling

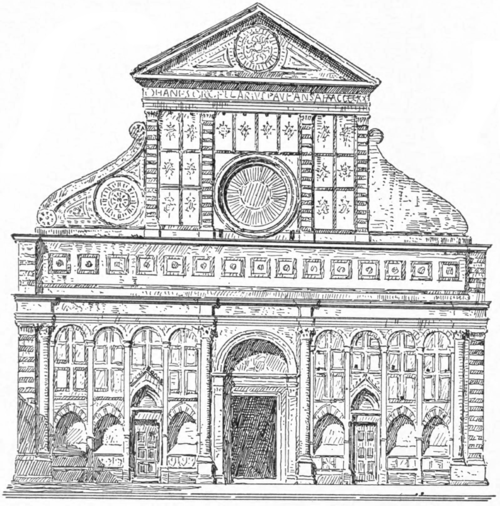

Fig. 13.—Façade of the Pazzi chapel.

with the traditional use of the entablature and the introduction of the arch sprung from the columns. But after the admirable logic of the mediæval arched systems of construction had been reached it appears strange that any designer should go back to this irrational combination.

In the portico (Fig. 13) the incongruities of design are of a still graver nature because they involve weakness of construction. The order of the interior is, as we have just seen, but a simulated order, and has no structural function, but in the portico a real Corinthian order is made to carry the barrel vault and dome above mentioned, and an attic wall which encloses the vaulting. But a classic order was never intended for such use, and cannot properly perform it. Such an order is adapted only to the support of crushing weight, and has no power of resistance to the thrusts of vaulting. The weight of the attic wall tends, indeed, in some measure to neutralize the force of the vault thrust, but this is not enough to render the structure secure, and unless the order were effectively steadied by some extraneous means the attic load would constitute a source of danger, as with any disturbance of its equilibrium by thrust its weight would hasten the overthrow of the system. How it is actually maintained is not apparent. No tie rods are visible beneath the vault, such as are common in Italian vaulted structures, which are rarely buttressed in an effective manner. Ties or clamps may, however, be concealed within the attic, though they would be less effective so placed. But in whatever way the system is held together, it is bad architecture, because the parts have no proper adaptation to their functions.

The ornamental treatment of the attic wall is worthy of notice. The surface is divided into panels by diminutive pilasters, and these panels are subdivided by mouldings in a manner which recalls the treatment of the attic of the Baptistery. The coupling of the pilasters was an innovation in the use of classic members, but it enabled the architect to avoid unpleasant proportions in these details. Single pilasters of the same magnitude would be too slender for the deep entablature over them, or to harmonize with the great Corinthian order below, while wider single ones would be stumpy and inelegant. The pair give good proportion in the total composition, while each pilaster is well proportioned in itself. Another noticeable point is the manner in which the central archivolt and the archivolts spanning the ends of the porch intersect the pilasters at the springing. This could not be avoided, because the pilasters cover the whole space on the entablature over the capitals of the columns, and leave no place for the archivolts. Thus the mediæval principle of intcrpenetration is carried over into the neo-classic design.

It should be observed that the details of this attic are wrought in stucco, so that we have with the beginning of the Renaissance a revival of a common ancient Roman practice of architectural deceit. The great order, however, is necessarily of stone, and its general proportions are good, though the details are poor in design, and coarse in execution.[4]

Fig. 14.—Badía of Fiesole.

The façade of the Pazzi has been considered as showing noteworthy originality of design. But there are older buildings in the neighbourhood to which it bears enough likeness to suggest its derivation from them. The façade of the Badía of Fiesole (Fig. 14) is one of these. By substituting a free-standing colonnade for the blind arcade of this front, and breaking its entablature and attic wall with an arch, we should get the leading features of the Pazzi front. Sant' Jacopo Soprarno, with its attic surmounting an open portico having an arcade on Corinthian columns, is also strongly suggestive of the same scheme. The features that are peculiar to the Pazzi, the arch breaking the entablature, the barrel vault sprung from the order, and the dome bisecting this vault, do little credit to the architect as a consistent designer.

Fig. 15.—Impost of San Lorenzo.

Two more important examples of church architecture in Florence, which appear to be mainly by Brunelleschi, are San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito. What part Brunelleschi had in the design of San Lorenzo is not perfectly clear,[5] but the main scheme was probably his, though the work was not completed until after his death. In the old sacristy of this church, which appears to be the part that was first built, the interior design of the Pazzi chapel is reproduced with some modifications of proportions and details, including the celled vault on a system of ribs, resting on pendentives. The church itself exhibits a frank return to primitive basilican forms and methods of construction, though with modifications and some additions. The nave has a flat wooden ceiling, but the aisles are covered with domical vaulting on salient transverse ribs, and over the crossing is a hemispherical dome on pendentives. In the arcades, which are carried on Corinthian columns like those of the portico of the Pazzi, the entablature blocks of late Roman design are reproduced in the impost (Fig. 15). The revival of this meaningless feature shows again how little impression the logic of mediæval art had made on the Italian mind, and what lack of discrimination in their borrowings from the antique the designers of the Renaissance often show. Whatever features the Roman models displayed were looked upon as authoritative, and copied without question; and the frequency with which this superfluous detail was reproduced in the subsequent architecture of the Renaissance has given it wide acceptance in more recent times. Notwithstanding the intention of the designer to revive the ancient style, mediæval features are conspicuous in San Lorenzo, and something of the mediæval logic of structural adjustment occurs in some details. Not only is the dome over the crossing supported on pendentives, which, in their developed form, are mediæval features and thus foreign to classic Roman design, but the piers sustaining this dome are compound, and consist of members of different proportions adjusted in the organic mediæval manner. The members which take part in the support of the aisle arcades are necessarily short, while those which carry the great pendentive arches are lengthened to reach the higher level from which those arches spring. But all of these members have the form of fluted Corinthian pilasters (Fig. 16). Thus were classic members used in ways that are foreign to classic principles, and their proportions altered with as much disregard for the rules of Vitruvius as the mediæval builders had shown.

Fig. 16.—Crossing pier of San Lorenzo.

The church of Santo Spirito, built after the architect's death, closely resembles San Lorenzo in its architectural character, though it is larger in scale. The entablature blocks occur in the arcades here also, but instead of a dome over the crossing as in San Lorenzo, there is a circular celled vault on converging ribs, like the vault of the Pazzi chapel. The interior is spacious and finely proportioned, but it presents no features that afford further illustration of the progress of neo-classic design.

The retrospective movement was carried further by the Florentine scholar and architect Leon-Batista Alberti, who, says Milizia, is justly regarded as one of the principal restorers of the architecture of antiquity.[6] His chief designs in church architecture are found in Santa Maria Novella of Florence, in San Francesco of Rimini, and in Sant' Andrea of Mantua. The first two of these are mediæval structures in which Alberti's work is confined to the remodelling of the exteriors, but the last was wholly designed by him, though the work was not completed within his lifetime, and the dome over the crossing is the work of another architect of a later time.

How much Alberti did to the façade of Santa Maria Novella, the part of the building to which his work is confined is not very clear. Vasari speaks vaguely as if the whole front were by him,[7] but from a foot-note by Milanesi it would appear that he merely completed a part which had been left unfinished by an older architect, and the work remaining by the older architect is said to include all below the first cornice except the central portal, which is attributed to Alberti. Milizia says[8] that although it is common to attribute the whole façade to Alberti, it has too much Gothic character to be entirely by him, and that therefore a part of it may, with more probability of correctness, be assigned to Giovanni Bettini, an older architect; but he adds that the central portal is undoubtedly by Alberti.

An examination of the monument itself would seem to show that the part below the first entablature, with exception of the great Corinthian columns and the central portal,, is mediæval work (Fig. 17). The whole Corinthian order, with the angle pilasters and the pedestals on which the order is raised, look like neo-classic work, and are probably by Alberti. This order is wholly different in character from mediæval design, and quite foreign to the mixture of Pisan Romanesque and Italian Gothic features of the distinctly mediæval part with which it is associated. The columns of the order are, however, of mediæval proportions, being eleven or twelve diameters in height, and they are built of small stones in a common mediæval manner. But these proportions were necessitated by the older work to which the order had to be adjusted, and the small masonry of which they are composed makes them harmonize with the older parts. The central portal has a round arch on fluted Corinthian pilasters framing in a deeply recessed rectangular opening with a classic lintel and jamb mouldings. It is noticeable that the arch does not spring directly from the capitals of the pilasters, but that the entablature block is interposed, as in Brunelleschi's arcades of San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito. Milizia, speaking

Fig. 17.—Façade of Santa Maria Novella.

of this feature in another work by the same architect, says: "In these arcades Alberti observed a rule always followed in the good ancient times, but since universally disregarded. The arches are not sprung from the columns, because this would be incorrect, but architraves [sic] are interposed. It would now be ridiculous to inculcate the importance of this rule, which is familiar to children."[9] This, like other notions to which the Renaissance gave currency, is a mistake. In inserting the entablature block at the arch impost Alberti did not follow a rule always observed in the ancient times. This feature is uncommon in ancient Roman art. It was, as before remarked, introduced by the late Roman architects, who, being accustomed to the use of the entablature over the column in the trabeate system which they had borrowed from the Greeks, did not see, when they began to spring arches from columns, that the entablature had no longer any reason for existence. The radical nature of the change wrought in architecture by the introduction of the arch was never grasped by the imperial Roman designers. First framing the arch with an order, thus uniting two contradictory systems, they afterwards, when, as in the basilica of Maxentius, springing the arches of vaulting from columns, thought that the rules required them to crown these columns with bits of entablature.

This façade appears to have been originally designed in the Pisan Romanesque style, with a tall, shallow blind arcade on pilaster-strips reaching across the ground story. But the Romanesque character was modified in some details, the portals having pointed arches, pointed arched niches sheltering tombs being ranged in the intervals between the pilaster-strips. How far the upper part of this façade had been left incomplete until Alberti took it in hand we have no means of knowing; but no mediæval features occur in it as it "now stands, except the circular opening in the central compartment. Upon this front, then, Alberti appears to have ingrafted the great Corinthian order, placing a wide pilaster paired with a column on each angle, breaking the entablature into ressauts to cover the columns, which have nothing else to support, and replacing the central portal with the existing one in the revived classic style. The preservation of the greater part of the mediæval work in the ground story made it impossible to get in more than the four columns in the great order, and these are necessarily spaced in an unclassic way, with a narrow interval in the middle and very wide ones on either side. To the upper compartment the architect has given an order of pilasters surmounted by a classic pediment, and flanked by screen walls over the aisle compartments in the form of gigantic reversed consoles, apparently the first of these features which became common thereafter in Renaissance fronts. The pilasters of this order are again four in number, and are set in pairs on either side of the circular opening, the width of this opening making it impossible to space them otherwise. We thus have in the clerestory compartment of this façade a forced arrangement of pilasters, which may have led to that alternation of wide and narrow intervals that became very common in the subsequent architecture of the Renaissance. The attic over the ground story, which extends across the entire front and answers to nothing in the interior of the building, is presumably also by Alberti.

The front of Santa Maria Novella is notable as the first mediæval one which was worked over by a Renaissance architect, and as a whole, notwithstanding that it is a patchwork of incongruous elements, it exhibits a remarkable unity of effect. The merit of Alberti's work here consists in its quietness. The applied orders are in low relief, their details are unobtrusive, and the mellowing effect of age on the beautiful marble incrusting has fused the whole front into an exquisite colour harmony that is almost unmatched elsewhere.

Very different is the west front of San Francesco of Rimini, in which Alberti has introduced a Roman composition without any admixture of mediæval elements. It is substantially a reproduction of the arch of Septimius Severus. The details are in higher relief here in conformity with the ancient model, and the ressauts of the entablature become correspondingly more salient. A ressaut of this kind is another feature of Roman art which has no justification on structural grounds, and to which there is nothing analogous in any reasonable style of architecture. To set a useless column in advance of an entablature and then make a ressaut to cover it, is irrational.

Alberti's capital work in church architecture is Sant' Andrea of Mantua, begun in 1472, the year of the architect's death, in which he made a frank return to Roman models in the structural forms of the whole edifice, as well as in the ornamental details—a thing that was rarely done by the architects of the Renaissance. The plan (Fig. 18) is, however, cruciform, and the dome over the crossing is supported in the Byzantine manner on pendentives. The nave (Plate II) has a barrel vault on massive square piers connected by arches, the intervals between the piers forming side chapels, and the lower part of each pier having a small

Plate II  Sant' Andrea |

Fig. 18.—Sant' Andrea, Mantua.

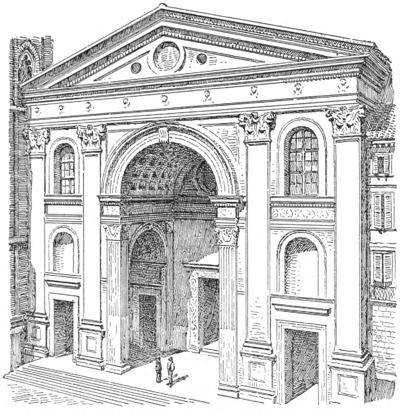

The west front of this church (Fig. 19) is again an adaptation of a Roman triumphal arch design. It is, in fact, as the plan (Fig. 18) shows, a great porch set against the true front, and has no correspondence in its parts with those of the building itself. In outline it is an unbroken rectangle crowned with a pediment. A very shallow order of Corinthian pilasters divides it into a wide central bay and two narrow ones. A great arch over a smaller order opens into a barrel-vaulted recess, on the three sides of which the entablature is returned. A rectangular portal, with square jambs and a cornice, opens into the nave, and

Fig. 19.—Façade of Sant' Andrea, Mantua.

an arch reaching to the entablature opens into the lateral compartment on each side, and each of these compartments has a barrel vault with its axis perpendicular to that of the great central one. The entablature of the small order is carried across the front of each lateral bay, dividing it into two stages, and the great order rises through it, embracing both stages, and forming an early instance of the so-called colossal order that became common in the later Renaissance. The great order is raised on pedestals, and both pedestals and pilasters of this order are panelled, while the small order rests directly on the pavement and its pilasters are fluted. It is noticeable that the design of the central arch is almost exactly like that of the central portal of Santa Maria Novella in Florence, the smaller entablature being broken into shallow ressauts over the pilasters, giving the same character to the imposts. The front as a whole has the quiet and refined character that distinguishes this architect's work in general.

Fig. 20.—Arch of Septimius Severus,

That Alberti derived all of these façades, and especially that of St. Andrea, from the Roman triumphal arch scheme a direct comparison will show; and the arch of Septimius Severus (Fig. 20) may, I think, be taken as the model that he had chiefly in mind. In Santa Maria Novella the mediæval scheme upon which he had to fit his work prevented such a disposition of the columns, and such general proportions as this model exhibits. He was obliged to make the lateral intercolumniations much wider than the central one, and to make the whole rectangle of the composition more oblong than that of the ancient monument; but in most other points he has followed the arch of Septimius Severus closely. As in the Roman design the entablature crowns the wall instead of the order, so that ressauts have to be formed to cover the columns. The insertion of the angle pilaster is a departure from the Roman scheme, and the placing of the stumpy pilaster of the attic over the great pilaster, instead of on the column, is another point of difference. But the general scheme of the ground story and attic will be seen to resemble that of the Roman design about as closely as the mediæval edifice on which it is ingrafted would allow. In San Francesco at Rimini the architect had a freer hand, and the order is treated in closer conformity with the ancient model as to the spacing of the columns and other details. The angles are treated precisely as they are in the arch of Septimius Severus, the pilasters being omitted, and the entablature at each end extending beyond the ressaut. The attic is omitted here, and the unfinished upper part of the façade is necessarily of different design.

In St. Andrea at Mantua the use of pilasters instead of columns, and the absence of ressauts in the great order, as well as the substitution of a pediment for the attic, make a great difference in the general character of the design; and yet the triumphal arch idea is even more strongly marked in this case, because it is not confined to the mere façade but extends to the form of the whole porch. The great barrel-vaulted recess is an exact reproduction of the central passageway of the Roman arch, and so are the lesser arches which open out of this recess on either side.

The triumphal arch idea applied to church fronts appears to be peculiar to Alberti. Most other architects among his contemporaries and immediate successors limit themselves to an application of the orders variously proportioned and disposed. In some cases the mediseval scheme of buttresses dividing the front into bays is retained, and this scheme is enriched with pilasters, or columns, and mouldings of classic profiling, as in the façade of the Duomo of Pienza by the Florentine architect Rossellino. In the later Renaissance façades, as we shall see, there is frequently no organic division of the whole front into bays by continuous members embracing its whole height, but superimposed pilasters and entablatures are variously disposed upon the surface without any suggestion, in the composition as a whole, of the triumphal arch idea (as in Vignola's fronts. Figs. 49 and 50). But in the characteristic Palladian scheme an organic division is formed by a great order of columns reaching to the top of the nave compartment, and overlapping a smaller order of pilasters extending across the whole front as in Figure 54.

The foregoing examples are enough to illustrate the character of Florentine church architecture, and that which was wrought elsewhere under Florentine influence, in the fifteenth century. These examples show us that the designers, while ostensibly striving to revive the antique forms, were in reality working more or less unconsciously on a foundation of mediæval ideas from which they could not free themselves. The inconsistencies of their work are largely due to the irreconcilable nature of the elements which they sought to unite, not appreciating the logic of mediæval art on the one hand, nor the true principles of the best art of antiquity on the other. The classic orders were entirely unsuited to the buildings to which they affixed them. They properly belong to a very different type of architecture which had been developed by the Greeks in ancient times, and the Greeks alone have used them with propriety. The Romans misapplied and deformed them, and the Italians of the Renaissance now surpassed the Romans in their misapplication and distortion. Many further illustrations of this will appear as we go on.

Early in the sixteenth century this architecture began to assume another phase in which the mediæval elements became less conspicuous, though they were not eliminated, and the imperial Roman features were more rigorously reproduced, yet they were never used with strict conformity to ancient models. This phase of the art was inaugurated by the architect Bramante after his settlement in Rome. We shall consider the Roman work of Bramante, in the following chapter.

- ↑ The term "Byzantine" is often applied loosely to buildings in which only the ornamental details have a Byzantine character. But the primary and distinguishing structural feature of Byzantine architecture is the dome on pendentives. The Byzantine features of the Pazzi are involved with others derived from different systems, but they are very distinct. The central vault, though of Gothic form, is supported on pendentives, and the true dome on pendentives occurs, as we have seen, in the sanctuary and the porch.

- ↑ The entablature does, however, occur under vaulting in some provincial Roman buildings, as in the Pantheon of Baalbek, where it forms the wall cornice from which the vaulting springs. But this, though not defensible, is less objectionable than the Renaissance scheme of an entablature passing through the imposts of archivolts.

- ↑ As in the arch of the apse of St. Paul outside the wall at Rome, and in the Baptistery of Florence.

- ↑ The character of these details will be discussed in the chapter on the carved ornament of the Renaissance.

- ↑ Cf. Vasari, Opere, vol. 2, p. 368 et seq., and Milancsi's foot-note, p. 370.

- ↑ Op. cit., vol. i, p. 200.

- ↑ Op. cit., vol. 2, p. 541.

- ↑ Op. cit., vol. i, p. 201.

- ↑ Op. cit., vol. i, p. 201.