CHAPTER XXI

"A POORHOUSE NOBODY"

A few days after the football game Nat Poole arrived at Oak Hall. Dave did not see him come, but Ben Basswood did, and he at once informed his chum of the fact.

"He is just as lordly as he ever was," said Ben. "I suppose he expects to cut quite a dash while he is here."

"I want nothing to do with him," answered Dave, quickly. "Do you know to what dormitory he was assigned?"

"No. 13—the one Gus Plum, Macklin, Puffers, and that crowd are in."

"It's just the kind of a crowd he belongs in, Ben. He and Gus Plum would make a good team. They are both rich, and both bullies."

It was not until the next day that Dave met Nat Poole in one of the lower halls. The newcomer stared coldly at Dave for a second, and then passed without either nodding or speaking.

Dave flushed—he could not exactly tell why. He had been on the point of speaking in a general way, but now he shut his mouth tightly. After that, during the day, he met Nat Poole several times, but not a word was exchanged.

"If he doesn't want to speak to me, I'm sure I don't want to speak to him," said Dave, in talking the matter over with Ben. "Perhaps he thinks himself too good."

"Let him go his own way, Dave. I shouldn't bother my head about him."

"Has he spoken to you?"

"Yes, but not in a very cordial manner. Each of us said, 'How do you do?' and that was all."

It was not long before it became apparent that Nat Poole and Gus Plum were growing very chummy. In the past the bully and Puffers had been close friends, but now Puffers was called away, to join his family, which had moved to the west.

"By the way," said Gus Plum, one day, when he and Poole and Macklin were in their dormitory alone. "As you come from Crumville you must have known Ben Basswood and Dave Porter."

"I knew Basswood pretty well, although he was not my style," answered the aristocratic youth. "Dave Porter I didn't want to know."

"Didn't want to know?" queried Macklin. "Didn't like him, I suppose. I don't like him myself."

"I want to know something of the people I associate with," went on Nat Poole, suggestively. "Unless a fellow has good family connections he usually doesn't amount to anything."

"Hasn't he good connections? Somebody told me he was a nephew or something like that, of a rich manufacturer named Wadsworth."

"A nephew!" cried Nat Pools. "He is no relation whatever to Oliver Wadsworth. Wadsworth merely took a fancy to him—I can't see why—and sent him to school here."

"Then, where did Porter come from?" asked Gus Plum, interested.

"Came from the Crumville poorhouse," answered Nat Poole. "He's a foundling—a mere nobody. That's the reason I don't want anything to do with him."

"Well, I never!" ejaculated the bully of the school. He mused for a moment and then gave a low whistle. "Wish I had known of this before," he went on. "Did you tell anybody else?"

"No—I haven't been asked. I thought you'd like to know it."

"You're right there. I like to pick the people I associate with, the same as you do. I don't want to know any poorhouse nobodies."

"It's a wonder Dr. Clay let him come here," ventured Macklin. "All the other boys, so far as I know, come from the best of families. Some of them wouldn't like it a bit to learn they were schooling with a poorhouse nobody."

"Hasn't he any relatives at all?"

"Not any, so far as is known. He was a pick-up—probably belonged to some low people who didn't want to pay for raising him."

"I see." Gus Plum's eyes began to glow. "Say, but I'm mighty glad you told me of this."

"Porter used to live with an old broken-down crank named Caspar Potts," went on Nat Poole. "Potts owed my father money, and there was quite a row before my old man could get what was coming to him. Dave Porter took Potts's part, and he and I had some sharp words. That is why he keeps his distance now. I let him understand that he wasn't in my class at all."

"Good for you!" cried the bully of Oak Hall. "After this I'll let him know what I think of him, too."

"Maybe we had better let the other fellows know about this," suggested Macklin. "I'm sure such fellows from fine families as Phil Lawrence and Lazy Day won't want to associate with a poorhouse upstart."

"Don't tell Porter I told you of this," put in Nat Poole, hastily. "I—well,—you understand——"

"Oh, that's all right," answered Gus Plum. "We shan't get you into any trouble."

The matter was talked over for half an hour, and when some of the other students came in the bully and the sneak mentioned what they had learned, in an off-hand way. As Dave was being talked of because of the run during the football game, the revelation created something of a sensation, and the news quickly spread until every boy at Oak Hall had heard it.

"By jinks, I can't believe this!" cried Sam Day, running up to Shadow, who was in the Hall gymnasium.

"Can't believe what, Lazy?" demanded the boy who loved to tell stories.

"What the fellows are telling about Dave Porter."

"What are they telling?"

"They say he is a nobody—that he was raised in a poorhouse, and that he doesn't know anything about his parents or relatives."

At this announcement Shadow Hamilton, who was on a bar, dropped to the floor.

"Is that true?"

"So they say."

"Who told you?"

"Blinky Watterson."

"And who told Blinky?"

"Chip Macklin. But Blinky heard it elsewhere, too. He said it must be so."

"I can't believe it," answered Shadow, soberly. "If it is true——" He stopped short.

"What?" demanded Sam Day.

"I—I shouldn't like to say, Lazy. Dave is a pretty nice chap, isn't he?"

"Yes, but——"

"Let's go and ask Phil Lawrence about this," and off the two students hurried to consult their leader.

During that day Dave noticed that a number of the students looked at him rather curiously. A few who in the past had spoken to him cordially now appeared not to see him when they went by. Once he passed Gus Plum, and the bully grinned in a sickly way but said nothing.

The blow fell on the following afternoon, shortly after the studies for the day were over. Dave, having nothing else to do, walked into the gymnasium, where he found Gus Plum and a dozen other pupils congregated. Dave began to swing upon some rings, when the bully promptly left off exercising.

"Come on, fellows," cried Plum, in a low but distinct voice, so that Dave might catch what he said. "I don't care to exercise with a nobody!" And he moved towards the door.

Several started to follow, including Macklin, who added, in a loud voice: "That's so—I like to pick my company."

"For shame, Plum!" came from Phil, who had just stepped into the gymnasium, after Dave.

"All right, Lawrence, you can associate with whom you please. I like to pick my company," answered the bully.

"And we don't pick poorhouse nobodies," added another boy, keeping close to the bully.

At the latter words Dave turned white, and allowed himself to drop to the floor. Like a flash he understood what had been going on and why some of his fellow-students had been treating him so strangely.

"What—what do you mean?" he faltered, facing the bully of Oak Hall.

"I mean just what I say, Dave Porter. I don't want anything to do with you," answered Gus Plum, loudly. "I can't understand why Dr. Clay allowed you to become a pupil here."

"Plum, you're a—a brute," interposed Phil, drawing himself up. "This sort of thing isn't fair at all," he went on, earnestly. "Dave is a good fellow, and you know it."

"Pooh! Stick up for him if you wish, but as for me, I don't intend to associate with a poorhouse fellow; yes, and a mere nobody at that."

Plum had scarcely uttered the words when he found himself in Dave's grip. The face of the country youth was like a sheet and his grasp was like that of steel.

"Gus Plum, you take that back!" he muttered, hoarsely. "Take it back, or I'll—I'll——"

Dave's look was so truly awful that the bully of Oak Hall actually shivered. He wanted to say something biting and sarcastic, but the words died on his lips.

"You—you—let go of me!" he faltered. "Let go!"

"I'm half of a mind to—to—strangle you!" returned Dave, and his grip did not lessen in the least. "You're a—a—I don't know what to call you."

"Let go!" and now Gus Plum began to struggle.

"Don't fight here," cried Phil, touching Dave on the shoulder. "If you do, you'll get yourself into trouble."

"But, Phil——" The words came almost pleadingly. Dave looked at his chum keenly, as if to read his innermost thoughts.

"I know—and I agree with you—Gus Plum is a brute, and Macklin is a snipe not worth considering. But don't have it out here."

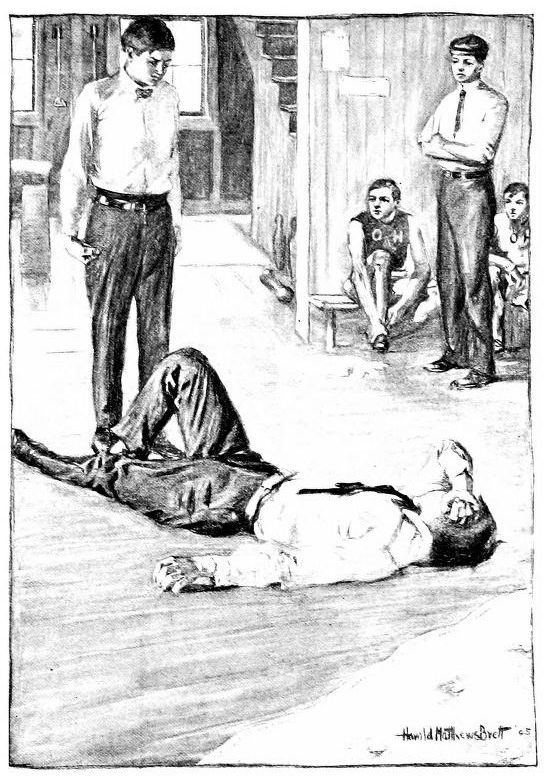

"All right, I'll take your advice," said Dave, and he gave the bully of Oak Hall a shove that landed him flat on his back. It took Plum but a moment to scramble to his feet.

"I'll show you!" he roared, squaring off. "I'll show you!"

"A fight! A fight!" was the shout.

"Now you'll see Gus polish off the poorhouse nobody," said one boy, but in such a low tone that only a few friends heard the remark.

"Dave, don't fight in here—arrange for a meeting later," urged Phil again. "This is no place for it. Somebody may come in, and——"

Phil had no time to say more, for Gus Plum was dancing around wildly. Now he let out with his right fist, and struck Dave on the shoulder.

It was the last straw, and casting prudence to the winds Dave assailed his foe with vigor. He struck the bully on the arm and in the chest, and then the two clinched and wrestled over a large portion of the gymnasium floor. Then they broke away again, and Dave was hit in the ear, and landed a telling blow on the bully's right eye.

"Cheese it! cheese it!" came the cry from a boy standing near the open door. "Here comes old Haskers!"

The cry was taken up by others. The second assistant teacher heard it, and at once, surmising that something was wrong, started toward the gymnasium on a run.

"I'll meet you some other time," growled Gus Plum, just as the teacher put in an appearance.

"All right—whenever you are ready I'll be," answered Dave, and then he and Phil hurried in one direction, while the bully and Macklin hurried in another.