Encyclopædia Britannica, Ninth Edition/Abbey

ABBEY, a monastery, or conventual establishment, under the government of an abbot or an abbess. A priory only differed from an abbey in that the superior bore the name of prior instead of abbot. This was the case in all the English conventual cathedrals, e.g., Canterbury, Ely, Norwich, &c., where the archbishop or bishop occupied the abbot's place, the superior of the monastery being termed prior. Other priories were originally offshoots from the larger abbeys, to the abbots of which they continued subordinate; but in later times the actual distinction between abbeys and priories was lost.

Reserving for the article Monasticism the history of the rise and progress of the monastic system, its objects, benefits, evils, its decline and fall, we propose in this article to confine ourselves to the structural plan and arrangement of conventual establishments, and a description of the various buildings of which these vast piles were composed.

The earliest Christian monastic communities with which we are acquainted consisted of groups of cells or huts collected about a common centre, which was usually the abode of some anchorite celebrated for superior holiness or singular asceticism, but without any attempt at orderly arrangement. The formation of such communities in the East does not date from the introduction of Christianity. The example had been already set by the Essenes in Judea and the Therapeutæ in Egypt, who may be considered the prototypes of the industrial and meditative communities of monks.

In the earliest age of Christian monasticism the ascetics were accustomed to live singly, independent of one another, at no great distance from some village, supporting themselves by the labour of their own hands, and distributing the surplus after the supply of their own scanty wants to the poor. Increasing religious fervour, aided by persecution, drove them further and further away from the abodes of men into mountain solitudes or lonely deserts. The deserts of Egypt swarmed with the cells or huts of these anchorites. Antony, who had retired to the Egyptian Thebaid during the persecution of Maximin, A.D. 312, was the most celebrated among them for his austerities, his sanctity, and his power as an exorcist. His fame collected round him a host of followers, emulous of his sanctity. The deeper he withdrew into the wilderness, the more numerous his disciples became. They refused to be separated from him, and built their cells round that of their spiritual father. Thus arose the first monastic community, consisting of anchorites living each in his own little dwelling, united together under one superior. Antony, as Neander remarks (Church History, vol. iii. p. 316, Clark's Trans.), "without any conscious design of his own, had become the founder of a new mode of living in common, Cœnobitism." By degrees order was introduced in the groups of huts. They were arranged in lines like the tents in an encampment, or the houses in a street. From this arrangement these lines of single cells came to be known as Lauræ, Λαῦραι, "streets" or "lanes."

The real founder of cœnobian monasteries in the modern sense was Pachomius, an Egyptian of the beginning of the 4th century. The first community established by him was at Tabennæ, an island of the Nile in Upper Egypt. Eight others were founded in his lifetime, numbering 3000 monks. Within 50 years from his death his societies could reckon 50,000 members. These cœnobia resembled villages, peopled by a hard-working religious community, all of one sex. The buildings were detached, small, and of the humblest character. Each cell or hut, according to Sozomen (H. E. iii. 14), contained three monks. They took their chief meal in a common refectory at 3 P.M., up to which hour they usually fasted. They ate in silence, with hoods so drawn over their faces that they could see nothing but what was on the table before them. The monks spent all the time, not devoted to religious services or study, in manual labour. Palladius, who visited the Egyptian monasteries about the close of the 4th century, found among the 300 members of the Cœnobium of Panopolis, under the Pachomian rule, 15 tailors, 7 smiths, 4 carpenters, 12 camel-drivers, and 15 tanners. Each separate community had its own œconomus, or steward, who was subject to a chief œconomus stationed at the head establishment. All the produce of the monks' labour was committed to him, and by him shipped to Alexandria. The money raised by the sale was expended in the purchase of stores for the support of the communities, and what was over was devoted to charity. Twice in the year the superiors of the several cœnobia met at the chief monastery, under the presidency of an Archimandrite ("the chief of the fold," from μάνδρα, a fold), and at the last meeting gave in reports of their administration for the year.

The cœnobia of Syria belonged to the Pachomian institution. We learn many details concerning those in the vicinity of Antioch from Chrysostom's writings. The monks lived in separate huts, κάλυβαι, forming a religious hamlet on the mountain side. They were subject to an abbot, and observed a common rule. (They had no refectory, but ate their common meal, of bread and water only, when the day's labour was over, reclining on strewn grass, sometimes out of doors.) Four times in the day they joined in prayers and psalms.

The necessity for defence from hostile attacks, economy of space, and convenience of access from one part of the community to another, by degrees dictated a more compact and orderly arrangement of the buildings of a monastic cœnobium. Large piles of building were erected, with strong outside walls, capable of resisting the assaults of an enemy, within which all the necessary edifices were ranged round one or more open courts, usually surrounded with cloisters. The usual Eastern arrangement is exemplified in the plan of the convent of Santa Laura, Mt. Athos (Laura, the designation of a monastery generally, being converted into a female saint).

| A. Gateway. | G. Refectory. |

| B. Chapels. | H. Kitchen. |

| C. Guest-house. | I. Cells. |

| D. Church. | K. Storehouses. |

| E. Cloister. | L. Postern Gate. |

| F. Fountain. | M. Tower. |

This monastery, like the Oriental monasteries generally is surrounded by a strong and lofty blank stone wall, enclosing an area of between 3 and 4 acres. The longer side extends to a length of about 500 feet. There is only one main entrance, on the north side (A), defended by three separate iron doors. Near the entrance is a large tower (M), a constant feature in the monasteries of the Levant. There is a small postern gate at (L.) The enceinte comprises two large open courts, surrounded with buildings connected with cloister galleries of wood or stone. The outer court, which is much the larger, contains the granaries and storehouses (K), and the kitchen (H), and other offices connected with the refectory (G). Immediately adjacent to the gateway is a two-storeyed guesthouse, opening from a cloister (C). The inner court is surrounded by a cloister (EE), from which open the monks' cells (II). In the centre of this court stands the catholicon or conventual church, a square building with an apse of the cruciform domical Byzantine type, approached by a domed narthex. In front of the church stands a marble fountain (F), covered by a dome supported on columns. Opening from the western side of the cloister, but actually standing in the outer court, is the refectory (G), a large cruciform building, about 100 feet each way, decorated within with frescoes of saints. At the upper end is a semi-circular recess, recalling the Triclinium of the Lateran Palace at Rome, in which is placed the seat of the Hegumenos or abbot. This apartment is chiefly used as a hall of meeting, the Oriental monks usually taking their meals in their separate cells. St Laura is exceeded in magnitude by the Convent of Vatopede, also on Mount Athos. This enormous establishment covers at least 4 acres of ground, and contains so many separate buildings within its massive walls that it resembles a fortified town. It lodges above 300 monks, and the establishment of the Hegumenos is described as resembling the court of a petty sovereign prince. The immense refectory, of the same cruciform shape as that of St Laura, will accommodate 500 guests at its 24 marble tables.

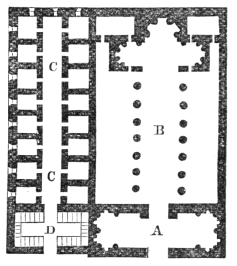

The annexed plan of a Coptic monastery, from Lenoir shows us a church of three aisles, with cellular apses, and two ranges of cells on either side of an oblong gallery.

| A. Narthex. | C. Corridor, with cells on each side. |

| B. Church. | D. Staircase. |

Monasticism in the West owes its extension and development to Benedict of Nursia (born A.D. 480). His rule was diffused with miraculous rapidity from the parent foundation on Monte Cassino through the whole of Western Europe, and every country witnessed the erection of monasteries far exceeding anything that had yet been seen in spaciousness and splendour. Few great towns in Italy were without their Benedictine convent, and they quickly rose in all the great centres of population in England, France, and Spain. The number of these monasteries founded between A.D. 520 and 700 is amazing. Before the Council of Constance, A.D. 1005, no fewer than 15,070 abbeys had been established of this order alone. The Benedictine rule, spreading with the vigour of a young and powerful life, absorbed into itself the older monastic foundations, whose discipline had too usually become disgracefully relaxed. In the words of Milman (Latin Christianity, vol. i. p. 425, note x.), "The Benedictine rule was universally received, even in the older monasteries of Gaul, Britain, Spain, and throughout the West, not as that of a rival order (all rivalry was of later date), but as a more full and perfect rule of the monastic life." Not only, therefore, were new monasteries founded, but those already existing were pulled down, and rebuilt to adapt them to the requirements of the new rule.

The buildings of a Benedictine abbey were uniformly arranged after one plan, modified where necessary (as at Durham and Worcester, where the monasteries stand close to the steep bank of a river), to accommodate the arrangement to local circumstances.

| Church. | |

| A. | High Altar. |

| B. | Altar of St Paul. |

| C. | Altar of St Peter. |

| D. | Nave. |

| E. | Paradise |

| F. | Towers |

| Monastic Buildings. | |

| G. | Cloister. |

| H. | Calefactory, with Dormitory over. |

| I. | Necessary. |

| J. | Abbot's house. |

| K. | Refectory. |

| L. | Kitchen. |

| M. | Bakehouse and Brewhouse. |

| N. | Cellar. |

| O. | Parlour. |

| P1. | Scriptorium, with Library over. |

| P2. | Sacristy and Vestry. |

| Q. | House of Novices—1. Chapel; 2. Refectory; 3. Calefactory; 4. Dormitory; 5. Master's Room; 6. Chambers. |

| R. | Infirmary—1-6 as above in the House of Novices. |

| S. | Doctor's House. |

| T. | Physic Garden. |

| U. | House for blood-letting. |

| V. | School. |

| W. | Schoolmaster's Lodgings. |

| X1X1 | Guest-house for those of superior rank. |

| X2X2 | Guest-house for the poor. |

| Y. | Guest-chamber for strange monks. |

| Menial Department. | |

| Z. | Factory |

| a. | Threshing-floor. |

| b. | Workshops. |

| c, c. | Mills. |

| d. | Kiln. |

| e. | Stables. |

| f. | Cowsheds. |

| g. | Goatsheds. |

| h. | Pig-sties. |

| i. | Sheep-folds. |

| k, k, k. | Servants' and workmen's sleeping chambers. |

| l. | Gardener's house. |

| m, m. | Hen and Duck house. |

| n. | Poultry-keeper's house. |

| o. | Garden. |

| p. | Cemetery. |

| q. | Bakehouse for Sacramental Bread. |

| r. | Unnamed in Plan. |

| s, s, s. | Kitchens. |

| t, t, t. | Baths. |

We have no existing examples of the earlier monasteries of the Benedictine order. They have all yielded to the ravages of time and the violence of man. But we have fortunately preserved to us an elaborate plan of the great Swiss monastery of St Gall, erected about A.D. 820, which puts us in possession of the whole arrangements of a monastery of the first class towards the early part of the 9th century. This curious and interesting plan has been made the subject of a memoir both by Keller (Zurich, 1844) and by Professor Willis (Arch. Journal, 1848, vol. v. pp. 86-117). To the latter we are indebted for the substance of the following description, as well as for the above woodcut, reduced from his elucidated transcript of the original preserved in the archives of the convent. The general appearance of the convent is that of a town of isolated houses with streets running between them. It is evidently planned in compliance with the Benedictine rule, which enjoined that, if possible, the monastery should contain within itself every necessary of life, as well as the buildings more intimately connected with the religious and social life of its inmates. It should comprise a mill, a bakehouse, stables and cow-houses, together with accommodation for carrying on all necessary mechanical arts within the walls, so as to obviate the necessity of the monks going outside its limits. The general distribution of the buildings may be thus described:—The church, with its cloister to the south, occupies the centre of a quadrangular area, about 430 feet square. The buildings, as in all great monasteries, are distributed into groups. The church forms the nucleus, as the centre of the religious life of the community. In closest connection with the church is the group of buildings appropriated to the monastic life and its daily requirements—the refectory for eating, the dormitory for sleeping, the common room for social intercourse, the chapter-house for religious and disciplinary conference. These essential elements of monastic life are ranged about a cloister court, surrounded by a covered arcade, affording communication sheltered from the elements, between the various buildings. The infirmary for sick monks, with the physician's house and physic garden, lies to the east. In the same group with the infirmary is the school for the novices. The outer school, with its head-master's house against the opposite wall of the church, stands outside the convent enclosure, in close proximity to the abbot's house, that he might have a constant eye over them. The buildings devoted to hospitality are divided into three groups,—one for the reception of distinguished guests, another for monks visiting the monastery, a third for poor travellers and pilgrims. The first and third are placed to the right and left of the common entrance of the monastery,—the hospitium for distinguished guests being placed on the north side of the church, not far from the abbot's house; that for the poor on the south side next to the farm buildings. The monks are lodged in a guest-house built against the north wall of the church. The group of buildings connected with the material wants of the establishment is placed to the south and west of the church, and is distinctly separated from the monastic buildings. The kitchen, buttery, and offices, are reached by a passage from the west end of the refectory, and are connected with the bakehouse and brewhouse, which are placed still further away. The whole of the southern and western sides is devoted to workshops, stables, and farm-buildings. The buildings, with some exceptions, seem to have been of one story only, and all but the church were probably erected of wood. The whole includes thirty-three separate blocks. The church (D) is cruciform, with a nave of nine bays, and a semicircular apse at either extremity. That to the west is surrounded by a semicircular colonnade, leaving an open "Paradise" (E) between it and the wall of the church. The whole area is divided by screens into various chapels. The high altar (A) stands immediately to the east of the transept, or ritual choir; the altar of St Paul (B) in the eastern, and that of St Peter (C) in the western apse. A cylindrical campanile stands detached from the church on either side of the western apse (FF).

The "cloister court" (G) on the south side of the nave of the church has on its east side the "pisalis" or "calefactory" (H), the common sitting-room of the brethren, warmed by flues beneath the floor. On this side in later monasteries we invariably find the chapter-house, the absence of which in this plan is somewhat surprising. It appears, however from the inscriptions on the plan itself, that the north walk of the cloisters served for the purposes of a chapter-house, and was fitted up with benches on the long sides. Above the calefactory is the "dormitory" opening into the south transept of the church, to enable the monks to attend the nocturnal services with readiness. A passage at the other end leads to the "necessarium" (I), a portion of the monastic buildings always planned with extreme care. The southern side is occupied by the "refectory" (K), from the west end of which by a vestibule the kitchen (L) is reached. This is separated from the main buildings of the monastery, and is connected by a long passage with a building containing the bakehouse and brewhouse (M), and the sleeping-rooms of the servants. The upper story of the refectory is the "vestiarium," where the ordinary clothes of the brethren were kept. On the western side of the cloister is another two story building (N). The cellar is below, and the larder and store-room above. Between this building and the church, opening by one door into the cloisters, and by another to the outer part of the monastery area, is the "parlour" for interviews with visitors from the external world (O). On the eastern side of the north transept is the "scriptorium" or writing-room (P1), with the library above.

To the east of the church stands a group of buildings comprising two miniature conventual establishments, each complete in itself. Each has a covered cloister surrounded by the usual buildings, i.e., refectory, dormitory, &c., and a church or chapel on one side, placed back to back. A detached building belonging to each contains a bath and a kitchen. One of these diminutive convents is appropriated to the "oblati" or novices (Q), the other to the sick monks as an "infirmary" (R).

The "residence of the physicians" (S) stands contiguous to the infirmary, and the physic garden (T) at the north-east corner of the monastery. Besides other rooms, it contains a drug store, and a chamber for those who are dangerously ill. The "house for blood-letting and purging" adjoins it on the west (U).

The "outer school," to the north of the convent area, contains a large school-room divided across the middle by a screen or partition, and surrounded by fourteen little rooms, termed the dwellings of the scholars. The head-master's house (W) is opposite, built against the side wall of the church. The two "hospitia" or "guest-houses" for the entertainment of strangers of different degrees (X1 X2) comprise a large common chamber or refectory in the centre, surrounded by sleeping apartments. Each is provided with its own brewhouse and bakehouse, and that for travellers of a superior order has a kitchen and store-room, with bed-rooms for their servants, and stables for their horses. There is also an "hospitium" for strange monks, abutting on the north wall of the church (Y).

Beyond the cloister, at the extreme verge of the convent area to the south, stands the "factory" (Z), containing workshops for shoemakers, saddlers (or shoemakers, sellarii), cutlers and grinders, trencher-makers, tanners, curriers, fullers, smiths, and goldsmiths, with their dwellings in the rear. On this side we also find the farm-buildings, the large granary and threshing-floor (a), mills (c), malt-house (d). Facing the west are the stables (e), ox-sheds (f), goat-stables (g), piggeries (h), sheep-folds (i), together with the servants' and labourers' quarters (k). At the south-east corner we find the hen and duck house, and poultry-yard (m), and the dwelling of the keeper (n). Hard by is the kitchen garden (o), the beds bearing the names of the vegetables growing in them, onions, garlic, celery, lettuces, poppy, carrots, cabbages, &c., eighteen in all. In the same way the physic garden presents the names of the medicinal herbs, and the cemetery (p) those of the trees, apple, pear, plum, quince, &c., planted there.

It is evident, from this most curious and valuable document, that by the 9th century monastic establishments had become wealthy, and had acquired considerable importance, and were occupying a leading place in education, agriculture, and the industrial arts. The influence such an institution would diffuse through a wide district would be no less beneficial than powerful.

The curious bird's eye view of Canterbury Cathedral and its annexed conventual buildings, taken about 1165, preserved in the Great Psalter in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge, as elucidated by Professor Willis with such admirable skill and accurate acquaintance with the existing remains,[1] exhibits the plan of a great Benedictine monastery in the 12th century, and enables us to compare it with that of the 9th, as seen at St Gall. We see in both the same general principles of arrangement, which indeed belong to all Benedictine monasteries, enabling us to determine with precision the disposition of the various buildings, when little more than fragments of the walls exist. From some local reasons, however, the cloister and monastic buildings are placed on the north, instead, as is far more commonly the case, on the south of the church. There is also a separate chapter-house, which is wanting at St Gall.

The buildings at Canterbury, as at St Gall, form separate groups. The church forms the nucleus. In immediate contact with this, on the north side, lie the cloister and the group of buildings devoted to the monastic life. Outside of these, to the west and east, are the "halls and chambers devoted to the exercise of hospitality, with which every monastery was provided, for the purpose of receiving as guests persons who visited it, whether clergy or laity, travellers, pilgrims, or paupers." To the north a large open court divides the monastic from the menial buildings, intentionally placed as remote as possible from the conventual buildings proper, the stables, granaries, barn, bakehouse, brewhouse, laundries, &c., inhabited by the lay servants of the establishment. At the greatest possible distance from the church, beyond the precinct of the convent, is the eleemosynary department. The almonry for the relief of the poor, with a great hall annexed, forms the pauper's hospitium.

The most important group of buildings is naturally that devoted to monastic life. This includes two cloisters, the great cloister surrounded by the buildings essentially connected with the daily life of the monks,—the church to the south, the refectory or frater-house here as always on the side opposite to the church, and furthest removed from it, that no sound or smell of eating might penetrate its sacred precincts, to the east the dormitory, raised on a vaulted undercroft, and the chapter-house adjacent, and the lodgings of the cellarer to the west. To this officer was committed the provision of the monks daily food, as well as that of the guests. He was, therefore, appropriately lodged in the immediate vicinity of the refectory and kitchen, and close to the guest-hall. A passage under the dormitory leads eastwards to the smaller or infirmary cloister, appropriated to the sick and infirm monks. Eastward of this cloister extend the hall and chapel of the infirmary, resembling in form and arrangement the nave and chancel of an aisled church. Beneath the dormitory, looking out into the green court or herbarium, lies the "pisalis" or "calefactory," the common room of the monks. At its northeast corner access was given from the dormitory to the necessarium, a portentous edifice in the form of a Norman hall, 145 feet long by 25 broad, containing fifty-five seats. It was, in common with all such offices in ancient monasteries, constructed with the most careful regard to cleanliness and health, a stream of water running through it from end to end. A second smaller dormitory runs from east to west for the accommodation of the conventual officers, who were bound to sleep in the dormitory. Close to the refectory, but outside the cloisters, are the domestic offices connected with it; to the north, the kitchen, 47 feet square, surmounted by a lofty pyramidal roof, and the kitchen court; to the west, the butteries, pantries, &c. The infirmary had a small kitchen of its own. Opposite the refectory door in the cloister are two lavatories, an invariable adjunct to a monastic dining-hall, at which the monks washed before and after taking food.

The buildings devoted to hospitality were divided into three groups. The prior's group "entered at the south-east angle of the green court, placed near the most sacred part of the cathedral, as befitting the distinguished ecclesiastics or nobility who were assigned to him." The cellarer's buildings, were near the west end of the nave, in which ordinary visitors of the middle class were hospitably entertained. The inferior pilgrims and paupers were relegated to the north hall or almonry, just within the gate, as far as possible from the other two.

Westminster Abbey is another example of a great Benedictine abbey, identical in its general arrangements, so far as they can be traced, with those described above. The cloister and monastic buildings lie to the south side of the church. Parallel to the nave, on the south side of the cloister, was the refectory, with its lavatory at the door. On the eastern side we find the remains of the dormitory, raised on a vaulted substructure, and communicating with the south transept. The chapter-house opens out of the same alley of the cloister. The small cloister lies to the south-east of the larger cloister, and still farther to the east we have the remains of the infirmary, with the table hall, the refectory of those who were able to leave their chambers. The abbot's house formed a small court-yard at the west entrance, close to the inner gateway. Considerable portions of this remain, including the abbot's parlour, celebrated as "the Jerusalem Chamber," his hall, now used for the Westminster King's scholars, and the kitchen and butteries beyond.

St Mary's Abbey, York, of which the ground-plan is annexed, exhibits the usual Benedictine arrangements. The precincts are surrounded by a strong fortified wall on three sides, the river Ouse being sufficient protection on the fourth side. The entrance was by a strong gateway (U) to the north. Close to the entrance was a chapel, where is now the church of St Olaf (W), in which the new comers paid their devotions immediately on their arrival. Near the gate to the south was the guest's-hall or hospitium (T). The buildings are completely ruined, but enough remains to enable us to identify the grand cruciform church (A), the cloister-court with the chapter-house (B), the refectory (I), the kitchen-court with its offices (K, O, O), and the other principal apartments. The infirmary has perished completely.

Some Benedictine houses display exceptional arrangements, dependent upon local circumstances, e.g., the dormitory of Worcester runs from east to west, from the west walk of the cloister, and that of Durham is built over the west, instead of as usual, over the east walk; but, as a general rule, the arrangements deduced from the examples described may be regarded as invariable.

The history of Monasticism is one of alternate periods of decay and revival. With growth in popular esteem came increase in material wealth, leading to luxury and worldliness. The first religious ardour cooled, the strictness of the rule was relaxed, until by the 10th century the decay of discipline was so complete in France that the monks are said to have been frequently unacquainted with the rule of St Benedict, and even ignorant that they were bound by any rule at all. (Robertson's Church History, ii. p. 538.) These alternations are reflected in the monastic buildings and the arrangements of the establishment.

| A. | Church. |

| B. | Chapter-house. |

| C. | Vestibule to do. |

| E. | Library or Scriptorium. |

| F. | Calefactory |

| G. | Necessary. |

| H. | Parlour. |

| I. | Refectory. |

| K. | Great Kitchen and Court. |

| L. | Cellarer's Office. |

| M. | Cellars. |

| N. | Passage to Cloister. |

| O. | Offices. |

| P. | Cellars. |

| Q. | Uncertain. |

| R. | Passage to Abbot's House. |

| S. | Passage to Common House. |

| T. | Hospitium. |

| U. | Great Gate. |

| V. | Porter's Lodge. |

| W. | Church of St Olaf. |

| X. | Tower. |

| Y. | Entrance from Bootham |

The reformation of these prevalent abuses generally took the form of the establishment of new monastic orders, with new and more stringent rules, requiring a modification of the architectural arrangements. One of the earliest of these reformed orders was the Cluniac. This order took its name from the little village of Clugny, 12 miles N.W. of Macon, near which, about A.D. 909, a reformed Benedictine abbey was founded by William, Duke of Auvergne, under Berno, abbot of Beaume. He was succeeded by Odo, who is often regarded as the founder of the order. The fame of Clugny spread far and wide. Its rigid rule was adopted by a vast number of the old Benedictine abbeys, who placed themselves in affiliation to the mother society, while new foundations sprang up in large numbers, all owing allegiance to the "archabbot," established at Clugny. By the end of the 12th century the number of monasteries affiliated to Clugny in the various countries of Western Europe amounted to 2000. The monastic establishment of Clugny was one of the most extensive and magnificent in France. We may form some idea of its enormous dimensions from the fact recorded, that when, A.D. 1245, Pope Innocent IV., accompanied by twelve cardinals, a patriarch, three archbishops, the two generals of the Carthusians and Cistercians, the king (St Louis), and three of his sons, the queen mother, Baldwin, Count of Flanders and Emperor of Constantinople, the Duke of Burgundy, and six lords, visited the abbey, the whole party, with their attendants, were lodged within the monastery without disarranging the monks, 400 in number. Nearly the whole of the abbey buildings, including the magnificent church, were swept away at the close of the last century. When the annexed ground-plan was taken, shortly before its destruction, nearly all the monastery, with the exception of the church, had been rebuilt. The church, the ground-plan of which bears a remarkable resemblance to that of Lincoln Cathedral, was of vast dimensions. It was 656 feet by 130 feet wide. The nave was 102 feet, and the aisles 60 feet high. The nave (G) had double vaulted aisles on either side. Like Lincoln, it had an eastern as well as a western transept, each furnished with apsidal chapels to the east. The western transept was 213 feet long, and the eastern 123 feet. The choir terminated in a semicircular apse (F), surrounded by five chapels, also semicircular. The western entrance was approached by an ante-church, or narthex (B), itself an aisled church of no mean dimensions, flanked by two towers, rising from a stately flight of steps bearing a large stone cross. To the south of the church lay the cloister-court (H), of immense size, placed much further to the west than is usually the case. On the south side of the cloister stood the refectory (P), an immense building, 100 feet long and 60 feet wide, accommodating six longitudinal and three transverse rows of tables. It was adorned with the portraits of the chief benefactors of the abbey, and with Scriptural subjects. The end wall displayed the Last Judgment. We are unhappily unable to identify any other of the principal buildings (N). The abbot's residence (K), still partly standing, adjoined the entrance-gate. The guest-house (L) was close by. The bakehouse (M), also remaining, is a detached building of immense size. The first English house of the Cluniac order was that of Lewes, founded by the Earl of Warren, cir. {{{AD 1077}}. Of this only a few fragments of the domestic buildings exist. The best preserved Cluniac houses in England are Castle Acre, Norfolk, and Wenlock, in Shropshire. Ground-plans of both are given in Britton's Architectural Antiquities. They show several departures from the Benedictine arrangement. In each the prior's house is remarkably perfect. All Cluniac houses in England were French colonies, governed by priors of that nation. They did not secure their independence nor become "abbeys" till the reign of Henry VI. The Cluniac revival, with all its brilliancy, was but short lived. The celebrity of this, as of other orders, worked its moral ruin. With their growth in wealth and dignity the Cluniac foundations became as worldly in life and as relaxed in discipline as their predecessors, and a fresh reform was needed. The next great monastic revival, the Cistercian, arising in the last years of the 11th century, had a wider diffusion, and a longer and more honourable existence. Owing its real origin, as a distinct foundation of reformed Benedictines, in the year 1098, to a countryman of our own, Stephen Harding (a native of Dorsetshire, educated in the monastery of Sherborne), and deriving its name from Citeaux (Cistercium), a desolate and almost inaccessible forest solitude, on the borders of Champagne and Burgundy, the rapid growth and wide celebrity of the order is undoubtedly to be attributed to the enthusiastic piety of St Bernard, abbot of the first of the monastic colonies, subsequently sent forth in such quick succession by the first Cistercian houses, the far-famed abbey of Clairvaux (de Clara Valle), A.D. 1116.

| A. | Gateway. |

| B. | Narthex. |

| C. | Choir. |

| D. | High-Altar. |

| E. | Retro-Altar. |

| F. | Tomb of St Hugh. |

| G. | Nave. |

| H. | Cloister. |

| K. | Abbot's House. |

| L. | Guest-House. |

| M. | Bakehouse. |

| N. | Abbey Buildings. |

| O. | Garden. |

| P. | Refectory. |

The rigid self-abnegation, which was the ruling principle of this reformed congregation of the Benedictine order, extended itself to the churches and other buildings erected by them. The characteristic of the Cistercian abbeys was the extremest simplicity and a studied plainness. Only one tower—a central one—was permitted, and that was to be very low. Unnecessary pinnacles and turrets were prohibited. The triforium was omitted. The windows were to be plain and undivided, and it was forbidden to decorate them with stained glass. All needless ornament was proscribed. The crosses must be of wood; the candlesticks of iron. The renunciation of the world was to be evidenced in all that met the eye. The same spirit manifested itself in the choice of the sites of their monasteries. The more dismal, the more savage, the more hopeless a spot appeared, the more did it please their rigid mood. But they came not merely as ascetics, but as improvers. The Cistercian monasteries are, as a rule, found placed in deep well-watered valleys. They always stand on the border of a stream; not rarely, as at Fountains, the buildings extend over it. These valleys, now so rich and productive, wore a very different aspect when the brethren first chose them as the place of their retirement. Wide swamps, deep morasses, tangled thickets, wild impassable forests, were their prevailing features. The "Bright Valley," Clara Vallis of St Bernard, was known as the "Valley of Wormwood," infamous as a den of robbers. "It was a savage dreary solitude, so utterly barren that at first Bernard and his companions were reduced to live on beech leaves."—(Milman's Lat. Christ, vol. iii. p. 335.)

All Cistercian monasteries, unless the circumstances of the locality forbade it, were arranged according to one plan. The general arrangement and distribution of the various buildings, which went to make up one of these vast establishments, may be gathered from that of St Bernard's own Abbey of Clairvaux, which is here given.

It will be observed that the abbey precincts are surrounded by a strong wall, furnished at intervals with watch towers and other defensive works. The wall is nearly encircled by a stream of water, artificially diverted from the small rivulets which flow through the precincts, furnishing the establishment with an abundant supply in every part, for the irrigation of the gardens and orchards, the sanitary requirements of the brotherhood, and for the use of the offices and workshops. The precincts are divided across the centre by a wall, running from N. to S., into an outer and inner ward,—Ψthe former containing the menial, the latter the monastic buildings. The precincts are entered by a gateway (P), at the extreme western extremity, giving admission to the lower ward.

| A. | Cloisters. |

| B. | Ovens, and Corn and Oil-mills. |

| C. | St Bernard's Cell. |

| D. | Chief Entrance. |

| E. | Tanks for Fish. |

| F. | Guest House. |

| G. | Abbot's House. |

| H. | Stables. |

| I. | Wine-press and Haychamber. |

| K. | Parlour. |

| L. | Workshops and workmen's Lodgings. |

| M. | Slaughter-house. |

| N. | Barns and Stables. |

| O. | Public Presse |

| P. | Gateway. |

| R. | Remains of Old Monastery. |

| S. | Oratory. |

| V. | Tile-works. |

| X. | Tile-kiln. |

| Y. | Water-courses. |

Here the barns, granaries, stables, shambles, workshops, and workmen's lodgings were placed, without any regard to symmetry, convenience being the only consideration. Advancing eastwards, we have before us the wall separating the outer and inner ward, and the gatehouse (D) affording communication between the two. On passing through the gateway, the outer court of the inner ward was entered, with the western façade of the monastic church in front. Immediately on the right of entrance was the abbot's house (G), in close proximity to the guest-house (F). On the other side of the court were the stables, for the accommodation of the horses of the guests and their attendants (H). The church occupied a central position. To the south were the great cloister (A), surrounded by the chief monastic buildings, and further to the east the smaller cloister, opening out of which were the infirmary, novices' lodgings, and quarters for the aged monks. Still further to the east, divided from the monastic buildings by a wall, were the vegetable gardens and orchards, and tank for fish. The large fish-ponds, an indispensable adjunct to any ecclesiastical foundation, on the formation of which the monks lavished extreme care and pains, and which often remain as almost the only visible traces of these vast establishments, were placed outside the abbey walls.

| A. | Church. |

| B. | Cloister. |

| C. | Chapter-House. |

| D. | Monks' Parlour. |

| E. | Calefactory. |

| F. | Kitchen and Court. |

| G. | Refectory. |

| H. | Cemetery. |

| I. | Little Cloister. |

| K. | Infirmary. |

| L. | Lodgings of Novices. |

| M. | Old Guest-House. |

| N. | Old Abbot's Lodgings. |

| O. | Cloister of Supernumerary Monks. |

| P. | Abbot's Hall. |

| Q. | Cell of St Bernard. |

| R. | Stables. |

| S. | Cellars and Storehouses. |

| T. | Water-course. |

| U. | Saw-mill and Oil-mill. |

| V. | Currier's Workshops. |

| X. | Sacristry. |

| V. | Little Library. |

| Z. | Undercroft of Dormitory. |

The Plan No. 2 furnishes the ichnography of the distinctly monastic buildings on a larger scale. The usually unvarying arrangement of the Cistercian houses allows us to accept this as a type of the monasteries of this order. The church (A) is the chief feature. It consists of a vast nave of eleven bays, entered by a narthex, with a transept and short apsidal choir. (It may be remarked that the eastern limb in all unaltered Cistercian churches is remarkably short, and usually square.) To the east of each limb of the transept are two square chapels, divided according to Cistercian rule by solid walls. Nine radiating chapels, similarly divided, surround the apse. The stalls of the monks, forming the ritual choir, occupy the four eastern bays of the nave. There was a second range of stalls in the extreme western bays of the nave for the fratres conversi, or lay brothers. To the south of the church, so as to secure as much sun as possible, the cloister was invariably placed, except when local reasons forbade it. Round the cloister (B) were ranged the buildings connected with the monks daily life. The chapter-house (C) always opened out of the east walk of the cloister in a line with the south transept. In Cistercian houses this was quadrangular, and was divided by pillars and arches into two or three aisles. Between it and the transept we find the sacristy (X), and a small book room (Y), armariolum, where the brothers deposited the volumes borrowed from the library. On the other side of the chapter-house, to the south, is a passage (D) communicating with the courts and buildings beyond. This was sometimes known as the parlour, colloquii locus, the monks having the privilege of conversation here. Here also, when discipline became relaxed, traders, who had the liberty of admission, were allowed to display their goods. Beyond this we often find the calefactorium or day-room—an apartment warmed by flues beneath the pavement, where the brethren, half-frozen during the night offices, betook themselves after the conclusion of lauds, to gain a little warmth, grease their sandals, and get themselves ready for the work of the day. In the plan before us this apartment (E) opens from the south cloister walk, adjoining the refectory. The place usually assigned to it is occupied by the vaulted substructure of the dormitory (Z). The dormitory, as a rule, was placed on the east side of the cloister, running over the calefactory and chapter-house, and joined the south transept, where a flight of steps admitted the brethren into the church for nocturnal services. Opening out of the dormitory was always the necessarium, planned with the greatest regard to health and cleanliness, a water-course invariably running from end to end. The refectory opens out of the south cloister at (G). The position of the refectory is usually a marked point of difference between Benedictine and Cistercian abbeys. In the former, as at Canterbury, the refectory ran east and west parallel to the nave of the church, on the side of the cloister furthest removed from it. In the Cistercian monasteries, to keep the noise and sound of dinner still further away from the sacred building, the refectory was built north and south, at right angles to the axis of the church. It was often divided, sometimes into two, sometimes, as here, into three aisles. Outside the refectory door, in the cloister, was the lavatory, where the monks washed their hands at dinner time. The buildings belonging to the material life of the monks lay near the refectory, as far as possible from the church, to the S.W. With a distinct entrance from the outer court was the kitchen court (F), with its buttery, scullery, and larder, and the important adjunct of a stream of running water. Further to the west, projecting beyond the line of the west front of the church, were vast vaulted apartments (SS), serving as cellars and storehouses, above which was the dormitory of the conversi. Detached from these, and separated entirely from the monastic buildings, were various workshops, which convenience required to be banished to the outer precincts, a saw-mill and oil-mill (UU) turned by water, and a currier's shop (V), where the sandals and leathern girdles of the monks were made and repaired.

Returning to the cloister, a vaulted passage admitted to the small cloister (I), opening from the north side of which were eight small cells, assigned to the scribes employed in copying works for the library, which was placed in the upper story, accessible by a turret staircase. To the south of the small cloister a long hall will be noticed. This was a lecture-hall, or rather a hall for the religious disputations customary among the Cistercians. From this cloister opened the infirmary (K), with its hall, chapel, cells, blood-letting house, and other dependencies. At the eastern verge of the vast group of buildings we find the novices' lodgings (L), with a third cloister near the novices' quarters and the original guest-house (M). Detached from the great mass of the monastic edifices was the original abbot's house (N), with its dining-hall (P). Closely adjoining to this, so that the eye of the father of the whole establishment should be constantly over those who stood the most in need of his watchful care,—those who were training for the monastic life, and those who had worn themselves out in its duties,—was a fourth cloister (O), with annexed buildings, devoted to the aged and infirm members of the establishment. The cemetery, the last resting-place of the brethren, lay to the north side of the nave of the church (H).

It will be seen that the arrangement of a Cistercian monastery was in accordance with a clearly-defined system, and admirably adapted to its purpose.

The base court nearest to the outer wall contained the buildings belonging to the functions of the body as agriculturalists and employers of labour. Advancing into the inner court, the buildings devoted to hospitality are found close to the entrance; while those connected with the supply of the material wants of the brethren,—the kitchen, cellars, &c.,—form a court of themselves outside the cloister, and quite detached from the church. The church refectory, dormitory, and other buildings belonging to the professional life of the brethren, surround the great cloister. The small cloister beyond, with its scribes' cells, library, hall for disputations, &c., is the centre of the literary life of the community. The requirements of sickness and old age are carefully provided for in the infirmary cloister, and that for the aged and infirm members of the establishment. The same group contains the quarters of the novices.

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

This stereotyped arrangement is further illustrated by the accompanying bird's eye view of the mother establishment of Citeaux. A cross (A), planted on the high road. directs travellers to the gate of the monastery, reached by an avenue of trees. On one side of the gate-house (B) is a long building (C), probably the almonry, with a dormitory above for the lower class of guests. On the other side is a chapel (D). As soon as the porter heard a stranger knock at the gate, he rose, saying, Deo gratias, the opportunity for the exercise of hospitality being regarded as a cause for thankfulness. On opening the door he welcomed the new arrival with a blessing—Benedicite. He fell on his knees before him, and then went to inform the abbot. However important the abbot's occupations might be, he at once hastened to receive him whom heaven had sent. He also threw himself at his guest's feet, and conducted him to the chapel (D) purposely built close to the gate. After a short prayer, the abbot committed the guest to the care of the brother hospitaller, whose duty it was to provide for his wants, and conduct the beast on which he might be riding to the stable (F), built adjacent to the inner gate-house (E). This inner gate conducted into the base court (T), round which were placed the barns, stables, cow-sheds, &c. On the eastern side stood the dormitory of the lay brothers, fratres conversi (G), detached from the cloister, with cellars and storehouses below. At (H), also outside the monastic buildings proper, was the abbot's house, and annexed to it the guest-house. For these buildings there was a separate door of entrance into the church (S). The large cloister, with its surrounding arcades, is seen at V. On the south end projects the refectory (K), with its kitchen at (I), accessible from the base court. The long gabled building on the east side of the cloister contained on the ground floor the chapter house and calefactory, with the monks' dormitory above (M), communicating with the south transept of the church. At (L) was the staircase to the dormitory. The small cloister is at (W), where were the carols or cells of the scribes, with the library (P) over, reached by a turret staircase. At (R) we see a portion of the infirmary. The whole precinct is surrounded by a strong buttressed wall (XXX), pierced with arches, through which streams of water are introduced. It will be noticed that the choir of the church is short, and has a square end instead of the usual apse. The tower, in accordance with the Cistercian rule, is very low. The windows throughout accord with the studied simplicity of the order.

An image should appear at this position in the text. If you are able to provide it, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images for guidance. |

The English Cistercian houses, of which there are such extensive and beautiful remains at Fountains, Rievaulx, Kirkstall, Tintern, Netley, &c., were mainly arranged after the same plan, with slight local variations. As an example, we give the ground-plan of Kirkstall Abbey, which is one of the best preserved and least altered. The church here is of the Cistercian type, with a short chancel of two squares, and transepts with three eastward chapels to each, divided by solid walls (222). The whole is of the most studied plainness. The windows are unornamented, and the nave has no triforium. The cloister to the south (4) occupies the whole length of the nave. On the east side stands the two-aisled chapter house (5), between which and the south transept is a small sacristy (3), and on the other side two small apartments, one of which was probably the parlour (6). Beyond this stretches southward the calefactory or day-room of the monks (14). Above this whole range of building runs the monks' dormitory, opening by stairs into the south transept of the church. At the other end were the necessaries. On the south side of the cloister we have the remains of the old refectory (11), running, as in Benedictine houses, from east to west, and the new refectory (12), which, with the increase of the inmates of the house, superseded it, stretching, as is usual in Cistercian houses, from north to south. Adjacent to this apartment are the remains of the kitchen, pantry, and buttery. The arches of the lavatory are to be seen near the refectory entrance. The western side of the cloister is, as usual, occupied by vaulted cellars, supporting on the upper story the dormitory of the lay brothers (8). Extending from the south-east angle of the main group of buildings are the walls and foundations of a secondary group of considerable extent. These have been identified either with the hospitium or with the abbot's house, but they occupy the position in which the infirmary is more usually found. The hall was a very spacious apartment, measuring 83 feet in length by 48 feet 9 inches in breadth, and was divided by two rows of columns. The fish-ponds lay between the monastery and the river to the south. The abbey mill was situated about 80 yards to the north-west. The mill-pool may be distinctly traced, together with the gowt or mill stream.

Fountains Abbey, first founded A.D. 1132, deserves special notice, as one of the largest and best preserved Cistercian houses in England. But the earlier buildings received considerable additions and alterations in the later period of the order, causing deviations from the strict Cistercian type. The church stands a short distance to the north of the river Skell, the buildings of the abbey stretching down to and even across the stream. We have the cloister (H) to the south, with the three-aisled chapter house (I) and calefactory (L) opening from its eastern walk, and the refectory (S), with the kitchen (Q) and buttery (T) attached, at right angles to its southern walk. Parallel with the western walk is an immense vaulted substructure (U), incorrectly styled the cloisters, serving as cellars and store-rooms, and supporting the dormitory of the conversi above. This building extended across the river. At its S.W. corner were the necessaries (V), also built, as usual, above the swiftly flowing stream. The monks' dormitory was in its usual position above the chapter-house, to the south of the transept.

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

As peculiarities of arrangement may be noticed the position of the kitchen (Q), between the refectory and calefactory, and of the infirmary (W) (unless there is some error in its designation) above the river to the west, adjoining the guest-houses (XX). We may also call attention to the greatly lengthened choir, commenced by Abbot John of York, 1203-1211, and carried on by his successor, terminating, like Durham Cathedral, in an eastern transept, the work of Abbot John of Kent, 1220-1247, and to the tower (D), added not long before the dissolution by Abbot Huby, 1494-1526, in a very unusual position at the northern end of the north transept. The abbot's house, the largest and most remarkable example of this class of buildings in the kingdom, stands south to the east of the church and cloister, from which it is divided by the kitchen court (K), surrounded by the ordinary domestic offices. A considerable portion of this house was erected on arches over the Skell. The size and character of this house, probably, at the time of its erection, the most spacious house of a subject in the kingdom, not a castle, bespeaks the wide departure of the Cistercian order from the stern simplicity of the original foundation. The hall (2) was one of the most spacious and magnificent apartments in mediæval times, measuring 170 feet by 70 feet. Like the hall in the castle at Winchester, and Westminster Hall, as originally built, it was divided by 18 pillars and arches, with 3 aisles. Among other apartments, for the designation of which we must refer to the ground-plan, was a domestic oratory or chapel, 4612 feet by 23 feet, and a kitchen (7), 50 feet by 38 feet. The whole arrangements and character of the building bespeak the rich and powerful feudal lord, not the humble father of a body of hard-working brethren, bound by vows to a life of poverty and self-denying toil. In the words of Dean Milman, "the superior, once a man bowed to the earth with humility, care-worn, pale, emaciated, with a coarse habit bound with a cord, with naked feet, had become an abbot on his curvetting palfrey, in rich attire, with his silver cross before him, travelling to take his place amid the lordliest of the realm." (Lat. Christ., vol. iii. p. 330.)

The buildings of the Austin Canons or Black Canons (so called from the colour of their habit) present few distinctive peculiarities. This order had its first seat in England at Colchester, where a house for Austin Canons was founded about A.D. 1105, and it very soon spread widely. As an order of regular clergy, holding a middle position between monks and secular canons, almost resembling a community of parish priests living under rule, they adopted naves of great length to accommodate large congregations. The choir is usually long, and is some times, as at Llanthony and Christ Church (Twynham), shut off from the aisles, or, as at Bolton, Kirkham, &c., is destitute of aisles altogether. The nave in the northern houses, not unfrequently, had only a north aisle, as at Bolton, Brinkburn, and Lanercost. The arrangement of the monastic buildings followed the ordinary type. The prior's lodge was almost invariably attached to the S.W. angle of the nave.

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

The annexed plan of the Abbey of St Augustine's at Bristol, now the cathedral church of that city, shows the arrangement of the buildings, which departs very little from the ordinary Benedictine type. The Austin Canons' house at Thornton, in Lincolnshire, is remarkable for the size and magnificence of its gate-house, the upper floors of which formed the guest-house of the establishment, and for possessing an octagonal chapter-house of Decorated date.

The Premonstratensian regular canons, or White Canons, had as many as 35 houses in England, of which the most perfect remaining are those of Easby, Yorkshire, and Bayham, Sussex. The head house of the order in England was Welbeck. This order was a reformed branch of the Austin canons, founded, A.D. 1119, by Norbert (born at Xanten, on the Lower Rhine, c. 1080) at Prémontré, a secluded marshy valley in the forest of Coucy, in the diocese of Laon. The order spread widely. Even in the founder's lifetime it possessed houses in Syria and Palestine. It long maintained its rigid austerity, till in the course of years wealth impaired its discipline, and its members sank into indolence and luxury. The Premonstratensians were brought to England shortly after A.D. 1140, and were first settled at Newhouse, in Lincolnshire, near the Humber. The ground-plan of Easby Abbey, owing to its situation on the edge of the steeply-sloping banks of a river, is singularly irregular. The cloister is duly placed on the south side of the church, and the chief buildings occupy their usual positions round it. But the cloister garth, as at Chichester, is not rectangular, and all the surrounding buildings are thus made to sprawl in a very awkward fashion. The church follows the plan adopted by the Austin canons in their northern abbeys, and has only one aisle to the nave—that to the north; while the choir is long, narrow, and aisleless. Each transept has an aisle to the east, forming three chapels.

The church at Bayham was destitute of aisle either to nave or choir. The latter terminated in a three-sided apse. This church is remarkable for its exceeding narrowness in proportion to its length. Extending in longitudinal dimensions 257 feet, it is not more than 25 feet broad. To adopt the words of Mr Beresford Hope—"Stern Premonstratensian canons wanted no congregations, and cared for no processions; therefore they built their church like a long room."

The Carthusian order, on its establishment by St Bruno, about A.D. 1084, developed a greatly modified form and arrangement of a monastic institution. The principle of this order, which combined the cœnobitic with the solitary life, demanded the erection of buildings on a novel plan. This plan, which was first adopted by St Bruno and his twelve companions at the original institution at Chartreux, near Grenoble, was maintained in all the Carthusian establishments throughout Europe, even after the ascetic severity of the order had been to some extent relaxed, and the primitive simplicity of their buildings had been exchanged for the magnificence of decoration which characterises such foundations as the Certosas of Pavia and Florence. According to the rule of St Bruno, all the members of a Carthusian brotherhood lived in the most absolute solitude and silence. Each occupied a small detached cottage, standing by itself in a small garden surrounded by high walls and connected by a common corridor or cloister. In these cottages or cells a Carthusian monk passed his time in the strictest asceticism, only leaving his solitary dwelling to attend the services of the Church, except on certain days when the brotherhood assembled in the refectory.

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

The peculiarity of the arrangements of a Carthusian monastery, or charter-house, as it was called in England, from a corruption of the French chartreux, is exhibited in the plan of that of Clermont, from Viollet le Duc. The whole establishment is surrounded with a wall, furnished at intervals with watch towers (R). The enclosure is divided into two courts, of which the eastern court, surrounded by a cloister, from which the cottages of the monks (I) open, is much the larger. The two courts are divided by the main buildings of the monastery, including the church, the sanctuary (A), divided from (B), the monks' choir, by a screen with two altars, the smaller cloister to the south (S) surrounded by the chapter-house (E), the refectory (X)—these buildings occupying their normal position—and the chapel of Pontgibaud (K). The kitchen with its offices (V) lies behind the refectory, accessible from the outer court without entering the cloister. To the north of the church, beyond the sacristy (L), and the side chapels (M), we find the cell of the sub-prior (a), with its garden. The lodgings of the prior (G) occupy the centre of the outer court, immediately in front of the west door of the church, and face the gateway of the convent (O). A small raised court with a fountain (C) is before it. This outer court also contains the guest-chambers (P), the stables, and lodgings of the lay brothers (N), the barns and granaries (Q), the dovecot (H), and the bakehouse (T). At (Z) is the prison. (In this outer court, in all the earlier foundations, as at Witham, there was a smaller church in addition to the larger church of the monks.) The outer and inner court are connected by a long passage (F), wide enough to admit a cart laden with wood to supply the cells of the brethren with fuel. The number of cells surrounding the great cloister is 18. They are all arranged on a uniform plan. Each little dwelling contains three rooms: a sitting-room (C), warmed with a stove in winter; a sleeping-room (D), furnished with a bed, a table, a bench, and a bookcase; and a closet (E). Between the cell and the cloister gallery (A) is a passage or corridor (B), cutting off the inmate of the cell from all sound or movement which might interrupt his meditations. The superior had free access to this corridor, and through open niches was able to inspect the garden without being seen. At (I) is the hatch or turn-table, in which the daily allowance of food was deposited by a brother appointed for that purpose, affording no view either inwards or outwards. (H) is the garden, cultivated by the occupant of the cell. At (K) is the wood-house. (F) is a covered walk, with the necessary at the end. These arrangements are found with scarcely any variation in all the charter-houses of Western Europe. The Yorkshire Charter-house of Mount Grace, founded by Thomas Holland the young Duke of Surrey, nephew of Richard II., and Marshal of England, during the revival of the popularity of the order, about A.D. 1397, is the most perfect and best preserved English example. It is characterised by all the simplicity of the order. The church is a modest building, long, narrow, and aisleless. Within the wall of enclosure are two courts. The smaller of the two, the south, presents the usual arrangement of church, refectory, &c., opening out of a cloister. The buildings are plain and solid. The northern court contains the cells, 14 in number. It is surrounded by a double stone wall, the two walls being about 30 feet or 40 feet apart. Between these, each in its own garden, stand the cells; low-built two-storied cottages, of two or three rooms on the ground-floor, lighted with a larger and a smaller window to the side, and provided with a doorway to the court, and one at the back, opposite to one in the outer wall, through which the monk may have conveyed the sweepings of his cell and the refuse of his garden to the "eremus" beyond. By the side of the door to the court is a little hatch, through which the daily pittance of food was supplied, so contrived by turning at an angle in the wall that no one could either look in or look out. A very perfect example of this hatch—an arrangement belonging to all Carthusian houses exists at Miraflores, near Burgos, which remains nearly as it was completed in 1480.

| A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

There were only nine Carthusian houses in England. The earliest was that at Witham in Somersetshire, founded by Henry II., by whom the order was first brought into England. The wealthiest and most magnificent was that of Shene or Richmond in Surrey, founded by Henry V. about A.D. 1414. The dimensions of the buildings at Shene are stated to have been remarkably large. The great court measured 300 feet by 250 feet; the cloisters were a square of 500 feet; the hall was 110 feet in length by 60 feet in breadth. The most celebrated historically is the Charter-house of London, founded by Sir Walter Manny A.D. 1371. the name of which is preserved by the famous public school established on the site by Thomas Sutton A.D. 1611.

An article on monastic arrangements would be incomplete without some account of the convents of the Mendicant or Preaching Friars, including the Black Friars or Dominicans, the Grey or Franciscans, the White or Carmelites, the Eremite or Austin Friars. These orders arose at the beginning of the 13th century, when the Benedictines, together with their various reformed branches, had terminated their active mission, and Christian Europe was ready for a new religious revival. Planting themselves, as a rule, in large towns, and by preference in the poorest and most densely populated districts, the Preaching Friars were obliged to adapt their buildings to the requirements of the site. Regularity of arrangement, therefore, was not possible, even if they had studied it. Their churches, built for the reception of large congregations of hearers rather than worshippers, form a class by themselves, totally unlike those of the elder orders in ground-plan and character. They were usually long parallelograms unbroken by transepts. The nave very usually consisted of two equal bodies, one containing the stalls of the brotherhood, the other left entirely free for the congregation. The constructional choir is often wanting, the whole church forming one uninterrupted structure, with a continuous range of windows. The east end was usually square, but the Friars Church at Winchelsea had a polygonal apse. We not unfrequently find a single transept, sometimes of great size, rivalling or exceeding the nave. This arrangement is frequent in Ireland, where the numerous small friaries afford admirable exemplifications of these peculiarities of ground-plan. The friars' churches were at first destitute of towers; but in the 14th and 15th centuries, tall, slender towers were commonly inserted between the nave and the choir. The Grey Friars at Lynn, where the tower is hexagonal, is a good example. The arrangement of the monastic buildings is equally peculiar and characteristic. We miss entirely the regularity of the buildings of the earlier orders. At the Jacobins at Paris, a cloister lay to the north of the long narrow church of two parallel aisles, while the refectory—a room of immense length, quite detached from the cloister—stretched across the area before the west front of the church. At Toulouse the nave also has two parallel aisles, but the choir is apsidal, with radiating chapels. The refectory stretches northwards at right angles to the cloister, which lies to the north of the church, having the chapter-house and sacristy on the east. As examples of English friaries, the Dominican house at Norwich, and those of the Dominicans and Franciscans at Gloucester, may be mentioned. The church of the Black Friars of Norwich departs from the original type in the nave (now St Andrew's Hall), in having regular aisles. In this it resembles the earlier examples of the Grey Friars at Reading. The choir is long and aisleless; an hexagonal tower between the two, like that existing at Lynn, has perished. The cloister and monastic buildings remain tolerably perfect to the north. The Dominican convent at Gloucester still exhibits the cloister-court, on the north side of which is the desecrated church. The refectory is on the west side, and on the south the dormitory of the 13th century. This is a remarkably good example. There were 18 cells or cubicles on each side, divided by partitions, the bases of which remain. On the east side was the prior's house, a building of later date. At the Grey or Franciscan Friars, the church followed the ordinary type in having two equal bodies, each gabled, with a continuous range of windows. There was a slender tower between the nave and choir. Of the convents of the Carmelite or White Friars we have a good example in the Abbey of Hulme, near Alnwick, the first of the order in England, founded A.D. 1240. The church is a narrow oblong, destitute of aisles, 123 feet long by only 26 feet wide. The cloisters are to the south, with the chapter-house, &c., to the east, with the dormitory over. The prior's lodge is placed to the west of the cloister. The guest-houses adjoin the entrance gateway, to which a chapel was annexed on the south side of the conventual area. The nave of the church of the Austin Friars or Eremites in London is still standing. It is of Decorated date, and has wide centre and side aisles, divided by a very light and graceful arcade. Some fragments of the south walk of the cloister of the Grey Friars exist among the buildings of Christ's Hospital or the Blue-Coat School. Of the Black Friars all has perished but the name. Taken as a whole, the remains of the establishments of the friars afford little warrant for the bitter invective of the Benedictine of St Alban's, Matthew Paris :—"The friars who have been founded hardly 40 years have built residences as the palaces of kings. These are they who, enlarging day by day their sumptuous edifices, encircling them with lofty walls, lay up in them their incalculable treasures, imprudently transgressing the bounds of poverty, and violating the very fundamental rules of their profession." Allowance must here be made for jealousy of a rival order just rising in popularity.

Every large monastery had depending upon it one or more smaller establishments known as cells. These cells were monastic colonies, sent forth by the parent house, and planted on some outlying estate. As an example, we may refer to the small religious house of St Mary Magdalene's, a cell of the great Benedictine house of St Mary's, York, in the valley of the Witham, to the south-east of the city of Lincoln. This consists of one long narrow range of building, of which the eastern part formed the chapel, and the western contained the apartments of the handful of monks of which it was the home. To the east may be traced the site of the abbey mill, with its dam and mil-lead. These cells, when belonging to a Cluniac house, were called Obedientiæ.

The plan given by Viollet le Due of the Priory of St Jean des Bons Hommes, a Cluniae cell, situated between the town of Avallon and the village of Savigny, shows that these diminutive establishments comprised every essential feature of a monastery,—chapel, cloister, chapter-room, refectory, dormitory, all grouped according to the recognised arrangement.

These Cluniac obedientiæ differed from the ordinary Benedictine cells in being also places of punishment, to which monks who had been guilty of any grave infringement of the rules were relegated as to a kind of penitentiary. Here they were placed under the authority of a prior, and were condemned to severe manual labour, fulfilling the duties usually executed by the lay brothers, who acted as farm-servants.

The outlying farming establishments belonging to the monastic foundations were known as villæ or granges. They gave employment to a body of conversi and labourers under the management of a monk, who bore the title of Brother Hospitaller—the granges, like their parent institutions, affording shelter and hospitality to belated travellers.

Authorities:—Dugdale, Monasticon; Fosbrooke, British Monachism; Helyot, Dictionnaire des Ordres Religieux; Lenoir, Architecture Monastique; Viollet le Due, Dictionnaire Raisonnée de l'Architecture Francaıse ; Walcott, Conventual Arrangement; Willis, Abbey of St Gall; Archæological Journal, vol. v., Conventual Buildings of Canterbury; Curzon, Monasteries of the Levant. (E. V.)

- ↑ The Architectural History of the Conventual Buildings of the Monastery of Christ Church in Canterbury. By the Rev. Robert Willis. Printed for the Kent Archaeological Society, 1869.