CHAPTER XI

judicial proceedings drum-dances and

entertainments.

I have again and again sought to impress upon the reader that the Eskimos are a peaceable and kindly race. There is no more striking proof of this, I think, than their primitive judicial process.

It is a mistake to suppose that the heathen Eskimos had no means of submitting any wrong they had suffered to the judgment of their fellows. Their judicial process, however, was of a quite peculiar nature, and consisted of a sort of duel. It was not fought with lethal weapons, as in the so-called civilised countries; in this, as in other things, the Greenlander went more mildly to work, challenging the man who had done him wrong to a contest of song or a drum-dance. This generally took place at the great summer meetings, where many people were assembled with their tents. The litigants stood face to face with each other in the midst of a circle of onlookers, both men and women, and, beat-

ing a tambourine or drum, each in turn sang satirical songs about the other. In these songs, which as a rule were composed beforehand, but were sometimes improvised, they related all the misdeeds of their opponent and tried in every possible way to make him ridiculous. The one who got the audience to laugh most at his jibes or invectives was the conqueror. Even such serious crimes as murder were often expiated in this way. It may appear to us a somewhat mild form of punishment, but for this people, with their marked sense of honour, it was sufficient; for the worst thing that can happen to a Greenlander is to be made ridiculous in the eyes of his fellows, and to be scoffed at by them. It has even happened that a man has been forced to go into exile by reason of a defeat in a drum-dance.

This drum-dance is still to be found upon the east coast. It seems clear that it must be an exceedingly desirable institution, and for my part I only wish that it could be introduced into Europe; for a quicker and easier fashion of settling quarrels and punishing evil-doers it is difficult to imagine.

The missionaries on the west coast of Greenland, unfortunately, do not seem to have been of the same opinion. Being a heathen custom, it was therefore, in their opinion, immoral and noxious as well; and on the introduction of Christianity they opposed it

and rooted it out. Dalager even teils us that 'there is scarcely any vice practised among the Greenlanders against which our missionaries preach more vehemently than they do against this dance, affirming that it is the occasion of all sorts of misbehaviour, especially among the young.' This policy he did not at all approve. He admits, indeed, that the dances may be the occasion of a few irregularities, but adds that if a girl has made up her mind to part with her virtue, she is not likely to select so unquiet a time and place; and one cannot but agree with him when he exclaims, 'And in truth, if people danced to such good purpose among us, we should presently see every second moralist and advocate transformed into a dancing-master.'

The result of this inconsiderate action on the part of the missionaries is that, in reality, no law and no forms of justice now exist in Greenland. The Europeans cannot, of course, or at any rate should not, mix themselves up in the Greenlanders' private affairs. But when, on some rare occasion, a crime of real importance occurs, the Danish authorities feel that they must intervene. The consequences of such intervention are sometimes rather surprising. At a settlement in North Greenland some years ago (so I have been told), a man who had killed his mother was punished by banishment

to a desert island. In order that he should be able to support himself in solitude, they had to give him a new kaiak, and a small store of food to begin with. Some time afterwards, the food having run out, he returned to the settlement and declared that he could not live on the island, because there was not enough game in the waters around it. He therefore settled down again in his old house, and the only change in his life brought about by his matricide was that he got a new kaiak.

The managers of the colonies sometimes have recourse to a more effective method of punishment in the case of women: it consists in excluding them for a certain time from dealing at the stores.

Besides being a judicial process, the drum-dance was also a great entertainment, and was often danced merely for the sake of pastime. In this case the dancers sang songs of various kinds, beating a drum the while, and going through a varied series of more or less burlesque writhings and contortions of the body. This is another consideration which ought to have made the missionaries think twice before abolishing the drum-dances, for amusement is a necessity of life, serving to refresh the mind, and is of quite peculiar importance for a people which, like the Greenlanders, inhabits an inhospitable region and has few diversions. To

make up for the loss of the drum-dances, they have now borrowed from the European whale-fishers and sailors many European dances, especially reels, which they have to some extent modified according to their own taste. At the colonies, the carpenter's shop, the blubber-loft, or some other large apartment, is generally used as a ball-room, and here dances take place as often as the managers or other authorities will give permission—generally once a week. In the other villages the dancing takes place in the Greenlanders' own houses.

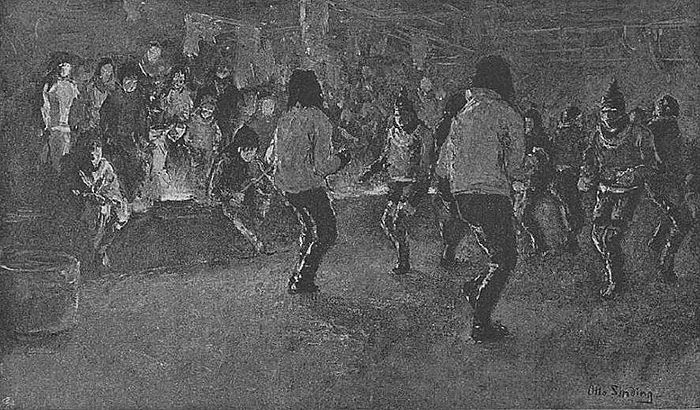

A Greenland ball offers a picturesque spectacle—the room half lighted by the train-oil lamps, and the crowd of people, young and old, all in their many coloured garments, some of them taking part in the dance, some standing as on-lookers in crowded groups along the walls and upon the sleeping-benches and seats. There is plenty of beauty and of graceful form, commingled with the most extravagant hideousness. Over the whole scene there is a sense of sparkling merriment, and in the dance a great deal of grace and accomplishment. The feet will often move so nimbly in the reel that the eye can with difficulty follow them. In former days the music was generally supplied by a violin, but now the accordion, too, is much in use.

The unhappy Eskimos who belong to the German or Herrnhut communities, of which there are several in the country, are forbidden to dance, and even to look at others dancing. If they do, they are excommunicated by the missionaries, or put down in their black books.Among other amusements, church-going takes a prominent place. They find the psalm-singing extremely diverting, and the women in particular are very much addicted to it.

The women, however, find shopping at least as entertaining. As the time for opening the stores approaches, they are to be seen, even in the winter snowstorms, standing in groups along the walls and waiting for the moment when the doors of Paradise shall be swung wide and they can rush in. Most of them do not want to buy anything, but they while away the hours during which the store is open, partly in examining all the European articles of luxury, especially stuffs and shawls, partly in flirting with the storekeepers, and partly in exchanging all sorts of more or less refined witticisms and 'larking' with each other.

The rush is particularly great every summer, after the arrival of the ships with cargoes of new wares from Europe. Then the stores are literally in a state of siege the whole day long. Like their European sisters, the Eskimo women are fond of

novelties of all sorts, so that as soon as they arrive the stores do a roaring trade in them. The main point, so far as I could understand, is that the wares shall be new; the use they are to be put to is a minor consideration.