CHAPTER III

The Technique of the Baton

THE BATON ITSELFBefore giving actual directions for the manipulation of the conductor's baton, it may be well to state that the stick itself should be light in weight, light in color, and from sixteen to twenty inches long. It must be thin and flexible, and should taper gradually from the end held in the hand to the point. Batons of this kind can be manufactured easily at any ordinary planing mill where there is a lathe. The kinds sold at stores are usually altogether too thick and too heavy. If at any time some adulating chorus or choir should present the conductor with an ebony baton with silver mountings, he must not feel that courtesy demands that it should be used in conducting. The proper thing to do with such an instrument is to tie a ribbon around one end and hang it on the wall as a decoration.

THE CONDUCTOR'S MUSIC STANDA word about the music desk may also be in order at this time. It should be made of wood or heavy metal so that in conducting one need not constantly feel that it is likely to be knocked over. The ordinary folding music stand made of light metal is altogether unsuitable for a conductor's use. A good substantial stand with a metal base and standard and wood top can be purchased for from three to five dollars from any dealer in musical instruments. If no money is available and the stand is constructed at home, it may be well to note that the base should be heavy, the upright about three and a half feet high, and the top or desk about fourteen by twenty inches. This top should tilt only slightly, so that the conductor may glance from it to his performers without too much change of focus. Our reason for mentioning apparently trivial matters of this kind is to guard against any possible distraction of the conductor's mind by unimportant things. If these details are well provided for in advance, he will be able while conducting to give his entire attention to the real work in hand.

HOLDING AND WIELDING THE BATONThe baton is ordinarily held between the thumb and first, second and third fingers, but the conductor's grasp upon it varies with the emotional quality of the music. Thus in a dainty pianissimo passage, it is often held very lightly between the thumb and the first two fingers, while in a fortissimo one it is grasped tightly in the closed fist, the tension of the muscles being symbolic of the excitement expressed in the music at that point. All muscles must be relaxed unless a contraction occurs because of the conductor's response to emotional tension in the music. The wrist should be loose and flexible, and the entire beat so full of grace that the attention of the audience is never for an instant distracted from listening to the music by the conspicuous awkwardness of the conductor's hand movements. This grace in baton-manipulation need not interfere in any way with the definiteness or precision of the beat. In fact an easy, graceful beat usually results in a firmer rhythmic response than a jerky, awkward one. For the first beat of the measure the entire arm (upper as well as lower) moves vigorously downward, but for the remaining beats the movement is mostly confined to the elbow and wrist. In the case of a divided beat (see pages 23 and 24) the movement comes almost entirely from the wrist.

POSITION OF THE BATONThe hand manipulating the baton must always be held sufficiently high so as to be easily seen by all performers, the elbow being kept well away from the body, almost level with the shoulder. The elevation of the baton, of course, depends upon the size of the group being conducted, upon the manner in which the performers are arranged, and upon whether they are sitting or standing. The conductor will accordingly vary its position according to the exigencies of the occasion, always remembering that a beat that cannot be easily seen will not be readily followed.

PRINCIPLES AND METHODS OF TIME BEATINGIf one observes the work of a number of conductors, it soon becomes evident that, although at first they appear to have absolutely different methods, there are nevertheless certain fundamental underlying principles in accordance with which each beats time, and it is these general principles that we are to deal with in the remainder of this chapter. It should be noted that principles rather than methods are to be discussed, since principles are universal, while methods are individual and usually only local in their application.

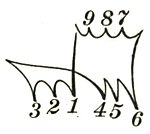

DIAGRAMS OF BATON MOVEMENTSThe general direction of the baton movements now in universal use is shown in the following figures.

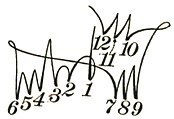

In actual practice however, the baton moves from point to point in a very much more complex fashion, and in order to aid the learner still further in his analysis of time beating an elaborated version of the foregoing

figures is supplied. It is of course understood that such

diagrams are of value only in giving a general idea of

these more complex movements and that they are not

to be followed minutely.

TWO-BEAT MEASURE | ||

THREE-BEAT MEASURE |

FOUR-BEAT MEASURE | |

SIX-BEAT MEASURE | ||

VERY SLOW TWO-BEAT MEASURE |

VERY SLOW THREE-BEAT MEASURE | |

SLOW FOUR-BEAT MEASURE |

SLOW NINE-BEAT MEASURE | |

SLOW TWELVE-BEAT MEASURE | ||

An examination of these figures will show that all baton movements are based upon four general principles:

- The strongest pulse of a measure (the first one) is always marked by a down-beat. This principle is merely a specific application of the general fact that a downward stroke is stronger than an upward one (cf. driving a nail).

- The last pulse of a measure is always marked by an up-beat, since it is generally the weakest part of the measure.

- In three- and four-beat measures, the beats are so planned that there is never any danger of the hands colliding in conducting vigorous movements that call for the use of the free hand as well as the one holding the baton.

- In compound measures the secondary accent is marked by a beat almost as strong as that given the primary accent.

NUMBER OF BEATS DETERMINED BY TEMPOThe fact that a composition is in 4–4 measure does not necessarily mean that every measure is to be directed by being given four actual beats, and one of the things that the conductor must learn is when to give more beats and when fewer.

If the tempo is very rapid, the 4–4 measure will probably be given only two beats, but in an adagio movement, as, e.g., the first part of the Messiah overture, it may be necessary to beat eight for each measure in order to insure rhythmic continuity. There are many examples of triple measure in which the movement is so rapid as to make it impracticable to beat three in a measure, and the conductor is therefore content merely to give a down-beat at the beginning of each measure; waltzes are commonly conducted by giving a down-beat for the first measure, an up-beat for the second, et cetera; a six-part measure in rapid tempo receives but two beats; while 9–8 and 12–8 are ordinarily given but three and four beats respectively.

It is not only annoying but absolutely fatiguing to see a conductor go through all manner of contortions in trying to give a separate beat to each pulse of the measure in rapid tempos; and the effect upon the performers is even worse than upon the audience, for a stronger rhythmic reaction will always be stimulated if the rhythm is felt in larger units rather than in smaller ones. But on the other hand, the tempo is sometimes so very slow that no sense of continuity can be aroused by giving only one beat for each pulse; hence, as already noted, it is often best to give double the number of beats indicated by the measure sign. In general, these two ideas may be summarized in the following rule: As the tempo becomes more rapid, decrease the number of beats; but as it becomes slower, increase the number, at the same time elaborating the beat so as to express more tangibly the idea of a steady forward movement.

In order to clarify these matters still further another series of figures is here supplied, these giving the more highly elaborated movements employed in slower tempos. As in the case of the diagrams on pages 23 and 24 these figures are intended to be suggestive only, and it is not expected that any one will copy the indicated movements exactly as given.

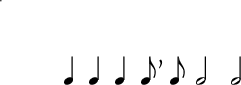

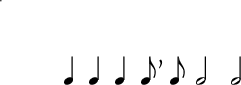

SHALL WE BEAT THE RHYTHM OR THE PULSE?In this same connection, the amateur may perhaps raise the question as to whether it is wise to beat the rhythm or the pulse in such a measure as- When a phrase begins with a tone that is on a fractional part of the beat; e.g., if the preceding phrase ends with an eighth, thus: ; for in this case the phrasing cannot be indicated clearly without dividing the beat.

- When there is a ritardando and it becomes necessary to give a larger number of beats in order to show just how much slower the tempo is to be. The second point is of course covered by the general rule already referred to.

The conductor must train himself to change instantly from two beats in the measure to four or six; from one to three, et cetera, so that he may be able at any time to suit the number of beats to the character of the music at that particular point. This is particularly necessary in places where a ritardando makes it desirable from the standpoint of the performers to have a larger number of beats.

THE DOTTED-QUARTER AS A BEAT NOTEAlthough covered in general by the preceding discussion, it may perhaps be well to state specifically that the compound measures 6–8, 9–8, and 12–8 are ordinarily taken as duple, triple, and quadruple measures, respectively. In other words, the dotted-quarter-note (FIVE- AND SEVEN-BEAT MEASURESAlthough only occasionally encountered by the amateur, five- and seven-beat measures are now made use of frequently enough by composers to make some explanation of their treatment appropriate. A five-beat measure (quintuple) is a compound measure comprising a two-beat and a three-beat one. Sometimes the two-beat group is first, and sometimes the three-beat one. If the former, then the conductor's beat will be down-up, down-right-up. But if it is the other way about, then the beat will naturally be down-right-up, down-up. "But how am I to know which comes first?" asks the tyro. And our answer is, "Study the music, and if you cannot find out in this way, you ought not to be conducting the composition."

Just as quintuple measure is a compound measure comprising two pulse-groups, one of three and the other of two beats, so seven-beat measure (septuple) consists of a four-beat group plus a three-beat one. If the fourbeat measure is first, the conductor's beat will be downleft-right-up, down-right-up; i.e., the regular movements for quadruple measure followed by those for triple; but if the combination is three plus four, it will be the other way about. Sometimes the composer helps the conductor by placing a dotted bar between the two parts of the septuple measure, thus:AN IMPORTANT PRINCIPLE OF TIME BEATINGThe most fundamental principle of time beating, and the one concerning which the young conductor is apt to be most ignorant, is the following: The baton must not usually come to a standstill at the points marking the beats, neither must it move in a straight line from one point to another, except in the case of the down beat; for it is the free and varying movement of the baton between any two beats that gives the singers or players their cue as to where the second of the two is to come. We may go further and say that the preliminary movement made before the baton arrives at what might be termed the "bottom" of the beat is actually more important than the "bottom" of the beat itself. When the baton is brought down for the first beat of the measure, the muscles contract until the imaginary point which the baton is to strike has been reached, relaxing while the hand moves on to the next point (i.e., the second beat) gradually contracting again as this point is reached, and relaxing immediately afterward as the hand moves on to the third beat. In the diagrams of baton movements given on preceding pages, the accumulating force of muscular contraction is shown by the gradually increasing thickness of the line, proceeding from the initial part of the stroke to its culmination; while the light curved line immediately following this culmination indicates the so-called "backstroke," the muscular relaxation. It is easy to see that this muscular contraction is what gives the beat its definiteness, its "bottom," while the relaxation is what gives the effect of continuity or flow. It will be noticed that when the baton is brought down on an accented beat, the beginning of the back-stroke is felt by the conductor as a sort of "rebound" of the baton from the bottom of the beat, and this sensation of rebounding helps greatly in giving "point" to these accented beats.

In order to understand fully the principle that we have just been discussing, it must be recalled that rhythm is not a succession of jerks, but is basically a steady flow, a regular succession of similar impulses, the word rhythm itself coming from a Greek stem meaning "flow." Like all other good things, this theory of continuous movement may be carried to excess, and one occasionally sees conducting that has so much "back-stroke" that there is no definiteness of beat whatsoever; in other words there is no "bottom" to the beat, and consequently no precision in the conducting. But on the other hand, there is to be observed also a great deal of conducting in which the beats seem to be thought of as imaginary points, the conductor apparently feeling that it is his business to get from one to another of these points in as straight a line as possible, and with no relaxation of muscle whatever. Such conductors often imagine that they are being very definite and very precise indeed in their directing, and have sometimes been heard to remark that the singers or players whom they were leading seemed exceedingly stupid about following the beat, especially in the attacks. The real reason for sluggish rhythmic response and poor attacks is, however, more often to be laid at the door of a poorly executed beat by the conductor than to the stupidity of the chorus or orchestra.[1]

HOW TO SECURE A FIRM ATTACKCoordinate with the discussion of continuous movement and back-stroke, the following principle should be noted: A preliminary movement sufficiently ample to be easily followed by the eye must be made before actually giving the beat upon which the singers or players are to begin the tone, if the attack is to be delivered with precision and confidence. Thus in the case of a composition beginning upon the first beat of a measure, the conductor holds the baton poised in full view of all performers, then, before actually bringing it down for the attack, he raises it slightly, this upward movement often corresponding to the back-stroke between an imaginary preceding beat and the actual beat with which the composition begins. When a composition begins upon the weak beat (e.g., the fourth beat of a four-pulse measure), the preceding strong beat itself, together with the back-stroke accompanying it, is often given as the preparation for the actual initial beat. In case this is done the conductor must guard against making this preliminary strong beat so prominent as to cause the performers to mistake it for the actual signal to begin. If the first phrase begins with an eighth-note (

THE ATTACK IN READING NEW MUSICFor working in rehearsal it is convenient to use some such exclamation as "Ready—Sing," or "Ready—Play," in order that amateur musicians may be enabled to attack the first chord promptly, even in reading new music. In this case the word "Ready" comes just before the preliminary movement; the word "Sing" or "Play" being coincident with the actual preliminary movement. In preparing for a public performance, however, the conductor should be careful not to use these words so much in rehearsing that his musicians will have difficulty in making their attacks without hearing them.

LENGTH OF THE STROKEThe length and general character of the baton movement depend upon the emotional quality of the music being conducted. A bright, snappy Scherzo in rapid tempo will demand a short, vigorous beat, with almost no elaboration of back-stroke; while for a slow and stately Choral, a long, flowing beat with a highly-elaborated backstroke will be appropriate. The first beat of the phrase in any kind of music is usually longer and more prominent, in order that the various divisions of the design may be clearly marked. It is in the length of the stroke that the greatest diversity in time beating will occur in the case of various individual conductors, and it is neither possible nor advisable to give specific directions to the amateur. Suffice it to say, that if he understands clearly the foregoing principles of handling the baton, and if his musical feeling is genuine, there will be little difficulty at this point.

NON-MEASURED MUSICThe directions for beating time thus far given have, of course, referred exclusively to what is termed "measured music," i.e., music in which the rhythm consists of groups of regularly spaced beats, the size and general characteristics of the group depending upon the number and position of the accents in each measure. There exists, however, a certain amount of non-measured vocal music, and a word concerning the most common varieties (recitative and Anglican chant) will perhaps be in order before closing our discussion of beating time.

RECITATIVEIn conducting the accompaniment of a vocal solo of the recitative style, and particularly that variety referred to as recitative secco, the most important baton movement is a down-beat after each bar. The conductor usually follows the soloist through the group of words found between two bars with the conventional baton movements, but this does not imply regularly spaced pulses as in the case of measured music, and the beats do not correspond in any way to those of the ordinary measure of rhythmic music. They merely enable the accompanying players to tell at approximately what point in the measure the singer is at any given time, the up-beat at the end of the group giving warning of the near approach of the next group.

THE ANGLICAN CHANTIn the case of the Anglican chant, it should be noted that there are two parts to each verse: one, a reciting portion in which there is no measured rhythm; the other, a rhythmic portion in which the pulses occur as in measured music. In the reciting portion of the chant, the rhythm is that of ordinary prose speech, punctuation marks being observed as in conventional language reading. This makes it far more difficult to keep the singers together, and in order to secure uniformity, some conductors give a slight movement of the baton for each syllable; others depend upon a down-beat at the beginning of each measure together with the lip movements made by the conductor himself and followed minutely by the chorus.

The beginning of the second part of the chant is indicated by printing its first syllable in italics, by placing an accent mark over it, or by some other similar device. This syllable is then regarded as the first accented tone of the metrical division of the chant, and, beginning with it, the conductor beats time as in ordinary measured music. If no other syllable follows the accented one before a bar occurs, it is understood that the accented syllable is to be held for two beats, i.e., a measure's duration. Final ed is always pronounced as a separate syllable.

The most important thing for an amateur to learn about conducting the Anglican chant is that before he can successfully direct others in singing this type of choral music, he must himself practically memorize each chant. The amateur should perhaps also be warned not to have the words of the first part of the chant recited too rapidly. All too frequently there is so much hurrying that only a few of the most prominent words are distinguishable, most of the connecting words being entirely lost. A more deliberate style of chanting than that in ordinary use would be much more in keeping with the idea of dignified worship. Before asking the choir to sing a new chant, it is often well to have the members recite it, thus emphasizing the fact that the meaning of the text must be brought out in the singing. In inaugurating chanting in churches where this form of music has not previously formed a part of the service, it will be well to have both choir and congregation sing the melody in unison for a considerable period before attempting to chant in parts.

THE NECESSITY OF PRACTICE IN HANDLING THE BATONNow that we have laid down the principles upon the basis of which our prospective conductor is to beat time, let us warn him once more that here, as in other things, it is intelligent practice that makes perfect, and that if he is to learn to handle the baton successfully, and particularly if he is to learn to do it so well that he need never give the slightest thought to his baton while actually conducting, hours of practice in beating time will be necessary. This practising should sometimes take place before a mirror, or better still, in the presence of some critical friend, so that a graceful rather than a grotesque style of handling the baton may result; it should also be done with the metronome clicking or with some one playing the piano much of the time, in order that the habit of maintaining an absolutely steady, even tempo may evolve. The phonograph may also be utilized for this purpose, and may well become an indispensable factor in training conductors in the' future, it being possible in this way to study the elements of interpretation as well as to practise beating time.

BATON TECHNIQUE NOT SUFFICIENT FOR SUCCESS IN CONDUCTINGIt must not be imagined that if one is fortunate enough to acquire the style of handling the baton which we have been advocating one will at once achieve success as a conductor. The factors of musical scholarship, personal magnetism, et cetera, mentioned in preceding pages, must still constitute the real foundation of conducting. But granting the presence of these other factors of endowment and preparation, one may often achieve a higher degree of success if one has developed also a well-defined and easily-followed beat. It is for this reason that the technique of time beating is worthy of some degree of serious investigation and of a reasonable amount of time spent in practice upon it.

- ↑ It is but a step from the conclusions arrived at above to a corollary relating to conducting from the organ bench. How does it happen that most choirs directed by an organist-conductor do not attack promptly, do not follow tempo changes readily, and do not in general present examples of good ensemble performance? Is it not because the organist is using his hands and feet for other purposes, and cannot therefore indicate to his singers the "continuous flow of rhythm" above referred to? When a conductor directing with a baton wishes to indicate a ritardando, he does so not merely by making the beats follow one another at longer intervals, but even more by making a more elaborate and more extensive movement between the beat culminations; and the musicians have no difficulty in following the baton, because it is kept continuously in motion, the points where the muscular contractions come being easily felt by the performers, because they can thus follow the rhythm in their own muscles by instinctive imitation. But when the organist-conductor wishes a ritardando, he merely plays more slowly, and the singers must get their idea of the slower tempo entirely through the ear. Since rhythm is a matter of muscle rather than of ear, it will be readily understood that conducting and organ-playing will never go hand in hand to any very great extent. There is, of course, another reason for the failure of many organists who try to play and conduct simultaneously, viz., that they are not able to do two things successfully at the same time, so that the chorus is often left to work out its own salvation as best it may; while, if the conducting is done by using the left hand, the organ end of the combination is not usually managed with any degree of distinction. Because of this and certain other wellknown reasons, the writer believes that choral music in general, and church music in particular, would be greatly benefited by a widespread return to the mixed chorus, led by a conductor with baton in hand, and accompanied by an organist.