Horse shoes and horse shoeing: their origin, history, uses, and abuses/Chapter VII

CHAPTER VII.

In connection with the archæological discoveries which have enabled us to fix, approximately, the period when shoeing was first introduced into, or practised in, Europe, I have deferred alluding, until now, to another matter which has excited much interest among antiquarians; this is the discovery of what are generally termed 'hipposandals'—objects in iron, of somewhat different shapes, but all apparently designed for the same purpose. In various museums in France, Germany, Switzerland, and Britain, these curious-looking instruments are exhibited under the designation of 'hipposandals,' or 'soleæ ferreæ,' owing to its being supposed,—because the Romans did not employ nailed-shoes, and these articles usually presenting themselves with Roman remains,—they were used as sandals for their horses' feet. A large number of archæologists,—at the head of whom are the Abbé Cochet,[1] M. Namur,[2] and Mr Roach Smith;[3] and

several Continental veterinary surgeons, with others, Professors Reynal of Alfort,[4] and Defays of Brussels,[5] MM. Fischer of Cessingen,[6] and Bieler of Rolle[7] (Switzerland)—are of this opinion; while others again, as Professor Quicherat of Chartes, MM. Castan and Delacroix of Besançon,[8] Captain Bial[9] of the French Artillery, and M. Quiquerez of Switzerland, are opposed to them, and think that these articles could never have been intended for, or worn as, shoes or sandals. Mr Roach Smith, the eminent archæologist, appears at one time to have held a middle opinion on the subject: 'It has been supposed they were used as temporary shoes for horses with tender feet, and they have been called stirrups; but both these notions are unsatisfactory.'[10] Some of these so-called sandals have been found in Gallo-Roman and

Frankish graves; many with Roman remains of various kinds, and others without any accompanying relics.

Though their forms are varied, yet it will be found that they chiefly belong to three models which, in all probability, have had the same uses, though they differ in shape. The first model may be described as a somewhat oblong or oval plate, or sole of metal, having a pyriform or circular opening in the middle (supposed to be for the purpose of allowing the moisture to escape from the horse's foot, as well as to give it air!). Transverse or crucial grooves are nearly always noticed on the under-surface of this plate, as if to make it bite the ground better. Two clips, sometimes four, rise from its sides, which are terminated at times in rings or hooks bending outwards, and the posterior part of the plate usually ends in a hook that projects more or less upwards.

The second form, found concurrently with the first, is much narrower in the sole, has a longer heel or spur than it, and is besides furnished with one in front which rises like the prow of a galley; clips also flank the sides, but these are irregular in number, sometimes one on each side, sometimes two, and in one instance I have seen (in the British Museum) only one on one side; these clips are often rather high, and nearly always terminate in eyes or hooks bending outwards. Sometimes there is an oval opening in the sole, but the grooves are seldom absent.

The third description is more curious. There is no hook in front, but the posterior one yet remains; and the two lateral appendages are prolonged, gradually tapering and bending towards each other as they incline to the front of the plate, until they meet and are welded together, when they are drawn out to form a strong hook, as if to compensate for the absence of the anterior crotchet of the second model.

So early as 1758, one of the first class was found at Culm, near Avenches, Switzerland;[11] but in this century they have been largely dug up over a comparatively wide expanse of territory. They have been discovered in the departments of the Sarthe and Moselle; in 1853 at Arques, in the Roman establishment of Archelles; at Caudebec-les-Elbeuf (the ancient Uggate); at Riviere-Thibonville (Eure); at Vieux, near Caen (the ancient Argægenus); at Vieil-Evreux (the ancient Mediolanum); at Chatelet, Dijon, Autun, Troyes, Montbeliard, Mandeure, and Seine-Inferieure. They have likewise been found in the Prankish cemeteries of Lorraine and Champagne; and in 1862, at the demolition of the ancient bridge of Reignac (Indre) a number of them were recovered, with a sword-blade, and coins of Adrian and Antoninus. In 1854, two more were extracted from the Roman road between Langres and Rheims; these are now in the Chalôns Museum. Another was picked up at Chateau de Beauregard (Hautes-Pyrénées) in 1856, and was presented to the Cluny Museum by M. Fould; and M. Widranges procured some from excavations at Remennecourt. Metz, Strasbourg, and Stuttgart have also furnished specimens. In Switzerland they have been found at Granges, Canton de Vaud. In Germany, at Schwarzacht, near Echternach, and particularly in the Roman camp at Dalheim, In England, at Stony Stratford; Spring-Head, in Kent; and in London.

As remarked, these articles are nearly always discovered on the sites of Roman buildings, contiguous to Roman stations, or with Roman reliquæ. Not unfrequently the three models are collected on the same site, and at the same depth, and with them have also been found the usual Gallo- or Romano-Celtic horse-shoes. Antiquarians have been greatly puzzled how to designate them; for some time they were stands or supports for lamps; afterwards they were stirrups; and then they figure as temporary shoes or sandals for horses with diseased or hoof-worn feet; as slippers that the Romans have strapped on their horses' limbs at night after long journeys; and as real defences for ordinary work—a step in advance of the sock with its metal sole; and lastly, as busandals, or bullock-slippers.

As the subject is one of more than ordinary interest, on account of the various hypotheses raised, and from the fact that these articles are now becoming somewhat common in museums, where they are duly labelled 'Hipposandals,' we will glance at the description and probable uses of some of them at least.

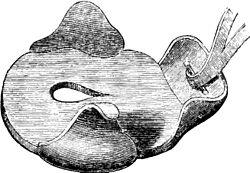

Dalheim affords a good instance of a locality in which all three forms have been discovered, accompanied by Roman remains of every description, as well as the ordinary nailed horse-shoe. In the first report from Professor Namur,[12] amongst other relics, he mentions having dug up several ordinary horse-shoes, and beside them were five pathological shoes. The latter are described as having their base oval, with a hole in the middle, and on each side towards the front a clip 2¾ inches high, ending in a hook-like process. Behind was a prolongation, also terminating in a hook. These strange articles were submitted to veterinary surgeon Fischer, of Cessingen, in 1851, who, on examining them, gave it as his opinion that they were 'hippopodes pathologiques,' intended to protect and cure hoofs too much worn, through default of shoeing.[13] This supposed sandal and its mode of attachment were delineated as in the accompanying figures (figs. 112, 113). In 1852–3, the excavations being

|

|

| fig. 112 | fig. 113 |

continued, with many articles belonging to the Roman period were found one ordinary shoe and several of the so-called pathological ƒers. One of these belonged to the first description, but no horse's foot, so far as I am aware, was attempted to be fitted into it (fig. 114).[14]

In 1854–5, it is again reported that a new form of hipposandal had been discovered, accompanied by another belonging to the second category.[15]

Allusion is made to the former discoveries: 'Besides some ordinary shoes, there have been found others which are distinguished by a singular form, and which we may designate hipposandals or "hippopodes pathologiques." The base of these shoes is oval in shape, and in some there is an opening in the middle. On each side, and near the front part, there is a clip (rebord) furnished with a round ear, and another rebord at the heel is terminated by a hook turned towards the ground. These shoes (ƒers) were attached by means of straps, which passed through the two ears and under the hook behind. It appears that it was made use of when the hoof was diseased or worn by journeying, particularly in mountainous countries. Such at least is the opinion of distinguished veterinary surgeons who have examined these shoes.' M, Namur then quotes the evidence of Fischer, who alludes to the writer in the 'United Service Gazette' we have already noticed, in saying: 'These shoes present much resemblance with the ancient shoes of Lycia,' &c.: showing how error is perpetuated and spread. We have no evidence to prove that horse-shoes were ever worn in Lycia; the resemblance of the Triquetra on a Lycian coin, to a shoe, was merely the fancy of a writer full of surmises and conjectures.

Namur continues: 'The use of shoes and straps (ƒers à courroies) is evidently much anterior to that of the nailed shoes.' Then reference is made to the new discovery. 'The excavations at Dalheim in 1854-5 have furnished two additional specimens. One, with clips, differs from those I have described, in that there is no hook behind. There is only a rebord pierced with two holes, in which are two oxidized nails with flat heads (fig. 115). The other specimen differs most essentially from the form generally known. It has also a base of an oval form, without an opening in the middle.

The two lateral clips towards the anterior part, instead of being separate and terminated by ears, are brought together and united into a point which is bent towards the front in a hook or ear projecting above the anterior convex border of the shoe. This form appears altogether new, and M. Fischer has never seen one like it in the veterinary schools of Alfort, or elsewhere' (fig. 116). Professor Defays, of Brussels, has rehabilitated fig. 112, and attached it to a horse's limb.

It will be observed that the fastening for the strap at the heel is rather awkwardly placed, and so arranged that no horse could walk with it.

Fischer,[16] in describing those of the first and second class, previously discovered, remarks that they were not attached by means of nails, but by straps or cords. When the ƒer was found to be adapted to the size of a particular foot, the prolongation at the heel (supposed to be previously on a level with the body of the 'sandal ') was then bent upwards in conformity with the dimensions and shape of the hoof. 'Je pense qu'ils étaient employés comme fers pathologiques destinés à garantir et à guérir les pieds déjà usés par une trop grande course, et auxquels il etait alors impossible d'adapter des fers à clous,' This camp of Dalheim alone furnished twelve of these slippers.

An example of what we may term the second description was found in the Hill of Sacrifices, at Granges, in Switzerland, where ordinary shoes had been excavated. They were four in number, according to M. Troyon, who asserted that they were found on the feet of a horse or mule. They are thus noticed by veterinary surgeon Bíeler, though no mention is made as to whether he or M. Troyon, or any other persons worthy of credit, were present when the remains were exhumed. 'There was found near Granges, Canton de Vaud, in the midst of Roman ruins, the skeleton of a horse or mule, the four feet of which were garnished with iron boots. These articles, now in the museums of Avenches and Bel-Air, were the soleæ ferreæ spoken of by the ancients. They are composed of a plate of iron destined to be applied under the foot, round at the toe, and following the shape of the hoof, but narrowing towards the middle of the quarters in such a way as to allow a portion of the heels to rest on the ground; then they widen a little towards the posterior part, which is provided with an appendage or branch, with a hook raised at a right angle in the soleæ of the fore feet, but less elevated in those of the hind. In front, at each corner of the toe, a strong clip (binçon), about 1½ inch high, carries a buckle or hook at its summit. These three buckles were quite sufficient to fix the solea in a firm manner, and it is scarcely possible that anything intervened between it and the hoof, for no traces of holes or rivets were perceived. The presence of straps leads to the supposition that these soleæ were applied during work only, and that they were removed when the animal entered its stable. Without this precaution, the straps, already dangerous by the wear to which they might subject the skin of the pastern, could not fail to be yet more pernicious if left continually tightened around the feet. It is remarkable that the clips are only at the corners of the toes, and that the iron sole should become narrowed at the part which corresponds to the quarters; was this to prevent slipping? Or did the Romans understand that the heels were elastic? It is very possible that their spirit of observation taught them something respecting this. The presence of these four soleæ on the feet of the same horse, sufficiently indicates that they were not used for maladies alone, as has been surmised, but habitually'[17] (fig. 117).

|

| fig. 117 |

The instrument found at Chateau Beauregard, Hautes-Pyrénées, and now in the Cluny Museum, belongs to the first class (figs. 118, 119), and is shown here in profile, as well as upper face. One of those discovered at Vieil-Evreux is also figured (fig. 120), and agrees with fig. 115 found at Dalheim. Of a more peculiar shape, but yet evidently intended for the same purpose, are two of the number recovered at Remennecourt, and delineated by M. de Widrange, an antiquarian of Bar-le-Duc (figs. 121, 122).

|

| fig. 118 |

Figure 121 is remarkable for its possessing no rings or ears, or anything by which it could be attached to the hoof, supposing it to have been intended for such a purpose; and figure 122 is not much better adapted for a sandal.

|

Professor Defays gives a drawing of another of this division, with an eye and ring posteriorly, two side clips without hooks, and the sole pierced by two round holes (fig 123).

Figures of the second type are as numerous, if not more so, than those of the first; and they have also been found with them, and with nailed shoes, in various excavations on Roman and

Frankish sites. The Museum of Cluny, France, exhibits one as a hipposandal, and is here shown in profile and upper surface (figs. 124, 125); and a similar one, found at Scrupt in 1846, is also delineated (fig. 126). This, M. de Widrange assured the Abbé Cochet, had been reported by the workman who found it, as yet attached to the limb of the animal by means of straps that had been first passed round the pastern, then through the eyelet in front, and buckled underneath the hook behind.

|

| fig. 126 |

The Abbé, however, receives this information with suspicion, and I think in this he is justified.[18] Figure 127 is a drawing of another of this class exhibited in the Museum of Besançon, which differs yet more in shape, though, unlike the last, it has only a single clip on each side.

|

| fig. 127 |

Specimens of the third model are not apparently so numerous. In addition to the one represented as found at Dalheim, an example is given of a still more peculiar article of this class found at Abbaye Wood, Canton St Saens, France, in 1861; the Abbé Cochet designates it a 'hippo-sandal.'[21] It is remarkable for the two stud-like processes fixed to its lower surface, and for the slight inclination towards the front of its united branches, one of which has been partially destroyed by oxidation (fig. 130).

Another good specimen of the third class is from an excavation in London, and is described by C. Roach Smith.[22] It differs but little from the one found in the Roman camp at Dalheim, and is six inches in length (fig. 131).

The British Museum contains six of these mysterious instruments, one of them more curious than any yet discovered. It has only one real lateral clip, the usual two being quite in front, where they are clumsily united to form a projecting hook. The sole is very narrow, and much oxidized on the ground surface, and the ordinary hook-like termination at the end is present (fig. 132).

The others belong to the three classes; one of the first has the side clips long and thin, and looking as if the hooks had been worn or rusted off, and the sole had been repaired by welding on a thin and narrow strip of iron in shape somewhat like a horse-shoe. The actual sole is six inches long, but the total length is six and three-quarters inches. The width across at the clips is four and three-quarters inches.

The others are somewhat different in length and width. One from the Bridge of Reignac, belonging to the second class, and presented by M. Picot to Sir J. Lubbock, by whom it was given to the museum, measures six inches long, three and a half wide, and the height of the front hook is two and three-quarters inches. It is inscribed 'Fer de Cheval.' Two of the specimens exhibited have the flat strips of iron forming the clips welded on to the sole, which in one of them is only two and three-eighths inches wide. To compensate for this want of breadth, these project a little from each side before being turned upwards at an acute angle. The ground-surface, as already mentioned, is notched or furrowed in various directions. The workmanship of all of them is very rough and primitive, but the welding appears to be solid, and the iron of excellent quality. They are comparatively light, the sole plate being generally the heaviest and strongest part.

Springhead, near Gravesend, Kent, so prolific in antiquities belonging to the British, Roman, and subsequent periods, furnishes us with two specimens of the first and second models. These, through the obliging kindness of Mr Sylvester, I have been allowed to inspect very carefully. Figure 133 has the oval or pear-shaped sole with the wide opening in the middle. One of the side clips has been oxidized completely through, and the other has been temporarily repaired; it is narrow, and the height is three and seven-eighths inches. The point of the hook inclines inwards. The sole is worn and oxidized to a thin edge in front, and is thicker behind towards the hook. The specimen is little more than an aggregation of rusty flakes; its length, not including the hook at the extremity, is five and a half inches, and

|

| fig. 133 |

the width across the sole between the clips is four and a half inches; behind this part it contracts very considerably, and in bending slightly upwards expands a little.

|

| fig. 134 |

Figure 134 is altogether a larger instrument. Its length within the front and back hooks is six and a half inches; the width between the side clips is four and a half inches, though the sole before and behind these is much narrower. This specimen is also much corroded, and the terminal hooks at the extremity of the side clips, if they ever were present, have disappeared. The face of the front hook is worn, as if it had been rubbed on the ground, or against some hard substance. The sole has transverse and longitudinal grooves. One side, as shown in this copy from a photograph, is much more worn than the other. The side clips are wide and have a slight twist inwards towards the front. One identical in shape with this was found in London, and is represented in the 'Archæological Journal' (vol. xi. p. 416). Another has been found at Langton, Wiltshire, and two discovered at Camerton are now in the museum of the Bristol Philosophical Institution.

Another example of the third type, resembling, in all its essential features, those found at Dalheim; Abbaye Wood, France; and in London, was picked up in the neighbourhood of Zazenhausen, near Stuttgart, among the roots of an old tree which was being removed. This was in a place where it appears the Romans had been really settled, for the remains of Roman baths, as well as a number of arms and such-like articles of undoubted Roman origin, have been gathered there. It consists of a ground plate (fig. 135), corresponding, as Grosz[23] informs us, with the form of a horse's sole; into it is riveted three studs, or we might term them calks, about half-an-inch high, the foremost of which is placed in the middle of the toe of the plate, and the other two are placed on each side behind. From both sides of the back part springs a clasp or band as is usual in this type, about an inch broad, which inclines forwards and upwards, uniting in the middle, about two inches above the ground plate, to form a round eyelet or ring, through which Grosz supposed a thong was drawn. There is a hook for the same purpose at the rear of the plate, this veterinarian observes; though whether the article served as a so-called pathological shoe for diseased hoofs, as a temporary expedient when horses had lost a shoe, or whether destined for hoofs which were too much worn to be shod, he could not decide.After an inspection of so many of these articles, which are apparently Roman, or belonging to the Roman period, the question arises, are they justly designated horse, mule, or bullock sandals? or have the Romans, or the people in whose territory they were found, ever employed them as a defence for the feet of their horses?

We have noticed that at one time they were supposed to be supports for lamps;[24] also lychnuchi pensiles, or hanging lamp-holders; the specimen found at Langton, Wiltshire, Sir S. Meyrick supposed to be a spur; then they were imagined to be ancient stirrups,[25] and now they are almost universally designated 'horse-sandals.' Professor Defays even contrives to adjust one to an animal's foot, though it must be rather uncomfortable about the heel; and veterinary surgeon Bieler asserts they were in ordinary use; while others declare they were only employed as temporary shoes, to be applied when the hoofs were too much worn or the feet diseased. Baron Ziegesar, of Berg, after reading the report of M. Namur regarding the Dalheim discoveries, wrote to the President of the Archæological Society of Luxembourg, informing him that, in his opinion, the sabots, or hippo-sandals, were intended to be put on the horses' feet at night during a halt, and that they were never used for marching.[26] It is, indeed, difficult to understand why defences should be required when the animals were at rest, and the hoofs not exposed to attrition, and why they should be left off at the very time they were likely to be needed. If difficult to be retained on the hoofs during the day, they would not be less so at night when the horses would be lying down and getting up frequently, and the uncouth projections behind, before, and on each side of the feet, would be certain to entangle the animals wearing them, and either cause these clumsy contrivances to be torn off, or expose the horses and their riders to serious accidents.

Mr Roach Smith, at first incredulous as to this application of these articles, appears to have become convinced of its correctness by discovering that in Holland horses yet wear sandals. 'At the present day in Holland it is usual to bind long flat iron shoes to the horses' feet. They are fastened with a strap of leather, and are somewhat in the form of an ordinary horse-shoe, but much longer and wider; and, did we not know they are commonly used, would seem almost as unsuitable as the iron shoes under consideration. Singular as the shape of these iron implements certainly is, we shall probably not be wrong in explaining them as veritable iron horse-shoes, such as Catullus refers to; and it is worthy of notice that at Springhead, where some were dug up at the same time and place, horse-shoes of the modern fashion were also found, as well as other objects in iron.' [27] To what extent they may be worn by the Dutch horses I do not know; but from the shape of them, which that gentleman has kindly permitted me to copy from an interesting but unpublished work[28] (fig. 136), it will be seen that they are very different to the Roman productions, and not at all intended for every-day wear. They are only used, I presume, for travelling on deep snow, or on marshy land where there is danger of sinking, and never on firm ground. I have seen similar snow or bog shoes used on horses in the Highlands of Scotland in removing peat. In this respect, as well as in their form, they resemble the snow shoes of the North-American hunters and the Scandinavians. The so-called hippo-sandals could never serve such a purpose, as they would no more preserve the animal wearing them from sinking than the shoe of the present day.Other authorities have not only decided that these antique contrivances were fastened on the feet of solipeds during the time of the Romans, but that they were in use until a comparatively recent age. Baron de Bonstetten remarks: 'The employment of horse-shoes of this form (modern) was only introduced by the Romans at a late period; those we see at Rome and in the "Museo Borbonico" at Naples are a kind of shots (souliers) which were attached by straps to the horse's feet, as the "induere" of Pliny attests.'[29] And the Abbé Cochet writes: 'I also know that when a very distinguished Belgian archæologist, M. Hagemans, the author of "The Cabinet d'Amateur," was at Milan in 1858, he saw in the collection of the Chevalier Ubaldo an iron hippo-sandal in magnificent preservation, and which did not appear to him to be very old. Prince Biondelli, a learned Milanese archæologist, who accompanied him, assured him that this horse sabot ought to belong to the 10th or 11th century. The Italian antiquary was also of opinion that the employment of shoes without nails was in vogue up to a late period of the middle ages.'[30]

With all due deference to the deservedly high reputation of the many authorities who have inspected and pronounced these iron utensils 'sandals,' after carefully examining and measuring them, and perusing the evidence brought forward to support that opinion, I cannot but conclude that the general opinion is an erroneous one, and for he following reasons: 1. These objects have not, so far as I am aware, been found in any country at a period which we might designate 'pre-Roman '—that is, in any region where the Romans have not been, nor before their invasion of the regions in which these articles have been discovered. 2. They have been found most frequently, I think, in places where the simple ordinary nail-shoe has been met with, and either with it, or so situated as to show they belonged to, and were in use at, the same period. 3. The evidence now collected would appear to indicate that shoeing with narrow plates and nails was largely practised in several countries, even before the arrival of the Romans; and also that in all probability the Romans themselves shod their horses in the ordinary manner at the same time that these strange-looking fabrications were in use for some purpose or other. The advantages of shoeing by means of nails must have been very striking to the Romans when they first became acquainted with it; so much so, that we should indeed think them extremely stupid if they did not avail themselves of it, and still had recourse to this unlikely contrivance. Cognizant of the art of defending the hoof by a thin narrow plate of iron, pierced with six holes, and which could be made in a few minutes, and firmly secured to the hoofs in as brief a space of time, it cannot for a moment be conceded that they would either allow their horses to travel unshod until they were foot-sore, and then apply this complicated sandal, with a sole much harder than the ground, to the bruised surface; or work their horses continually with shoes which must have tasked the abilities of their blacksmiths to fabricate in less than an hour, and have required more than three or four times the quantity of iron that the Gallic or British shoe did. Though not an equestrian nation, we must give the Romans credit for common sense. As for their working their horses all day without any foot-cover, and applying these at night when they were not required, the idea is perfectly absurd. This is admitting that these articles were really intended to be attached to horses' feet; and that, though nail-shoeing was well known, and its efficacy and simplicity were recognized, the Romans, or the people among whom they were living, persisted in expending four times the weight of iron, twenty times the amount of labour, and a dozen times the quantity of charcoal.

But I cannot believe that these 'hippo-sandals' were ever made for such a purpose. Extremely few horses, if any, could travel with those of the first class on roads, in ascending or descending steep places, nor yet move at any speed. The projecting fastening behind, and the inside clip, as well as the insecurity and situation of the attachment, and the weight of the iron, all forbid this supposition.

For the second and third classes, I need only say that horses could neither travel nor yet stand in them. With far more reason might we expect two or three ranks of soldiers to walk, run, and manœuvre in close order with Canadian snow-shoes on their feet, than to see a horse walk, trot, and gallop with these so-called sandals. The majority of the second class could not be put on the hoofs, to begin with; and none of the third class could, by any possibility, serve such a purpose. A glance at the shape of these will show this to be the fact.

Besides, not one of those I have examined, though many appear to have been subjected to wear in other respects, show any marks of hoof wear; that is, still granting that they could be fastened to the extremity of the limb. It is well known that a horse's shoes, after being a short time subjected to use on hard ground, become rounded over at the toe, where the greatest amount of wear occurs; also that the foot-surface, even with the shoe firmly nailed to the wall, becomes worn and channeled where any play or friction takes place. This is well seen in an old horseshoe. No such evidences appear on the best-preserved of these so-called sandals. On the contrary, the upper surface of the sole is entirely free from traces of friction of any kind, and the under or ground-surface is usually most worn towards the middle, the extremities being sharp rather than rounded over. There is not the faintest trace of their having been worn at all by horses. No nation ever offered any contrivance so unsuited to the object to be attained as these so-called hippo-sandals, if we suppose them to have been intended for horses' feet. There is nothing at all reasonable in the supposition; and in this opinion I find I am supported by MM. Delacroix and Quiquerez, antiquarians who have had abundant opportunities of studying this matter, and have availed themselves of them. M. Quiquerez writes: 'The many excavations made by us in the Roman villas, camps, and castles of the Bernese Jura have never afforded us any of these calceæ ferreæ, or hippo-sandals, with which people would like to shoe the feet of Roman horses. But we have seen plenty of these articles, without being able to comprehend how a horse, starting at a gallop on an uneven road, could, for an instant even, carry such a chaussure. Always, however, out of respect for the opinion of others, we have never cast a doubt on the use of the socks for the Roman horses, because their employment for this purpose may have been one of those unfortunate essays of their military chiefs. Elsewhere in Switzerland, so few of these strap-shoes (fers à courroies) have been found, that it appears probable such a mode of shoeing, if it did exist, was for but a brief period. On the contrary, it is our conviction that long before the arrival of the Romans among the Gauls, the Sequaniæ, Helvetiæ, and Rouraks, in the vicinity of the Jura mountains, shod their horses as we now do. The almost total absence of calceæ ferreæ in our districts confirms this opinion; which is, it is true, in disaccord with that of some archæologists, who only introduce nail-shoeing in the Roman armies towards the 10th century of our era, and as an importation by the nations of the North.'[31]

And M. Delacroix, when describing the shoes found in Besançon, makes a similar protest against these articles being designated hippo-sandals. 'Modern science, in the face of ancient authors mentioning horse-shoes, thinks it ought to consider as such the objects whose use is as yet unknown, which are found in ancient roadways, and to which it has been imagined to give the name of hippo-sandals. The figure of some hippo-sandals might, justly or unjustly, have authorized such an explanation of their use; the collection of a tolerably large number of these articles, however, dispels the illusion. There are in the Archaeological Museum of Besançon hippo-sandals provided with long hooks before and behind, and even on the sides. A horse furnished with such a chaussure could not walk four steps without mutilating himself and falling. What is more, we have hippo-sandals the two flanks of which are united above, and which could never make a shoe for a horse, even if the animal were standing still. . . . . . . When we see the same ground containing hippo-sandals and nailed shoes, it must be evident that the first were not destined for the feet of horses. It has been said that at least they might be employed for horses' feet in a bad condition; but besides the impossibility of using many of them for any such purpose, and which is obvious enough, we have discovered in our excavations a shoe intended for a diseased foot, one of the branches of which has been enlarged to an extraordinary degree, so as to cover one-half of the sole.'

Veterinary surgeon Duplessis, of the French artillery, likewise announces his disapproval of the name and the use given to these contrivances. Referring to the opinions of the Abbé Cochet and M. Megnin, he says: 'These gentlemen justly deny the possibility of these strangely formed bits of irons ever having been placed under horses' feet. I am of their opinion, for everything is opposed to such an admission. The lightness and freedom required for rapid paces would prevent their employment in this way, as well as the impossibility of fixing on a round flat foot a heavy ill-balanced machine like this. The example afforded by all the human foot-covers would show them (the Romans) that it was at least indispensable that it should resemble in shape the plantar surface of the foot.'[32] M. Delacroix,[33] since the publication of his opinion adverse to these instruments being horse-sandals, has suddenly come to the conclusion that they are ox-sandals. 'The number of these articles in the Besançon Museum has actually increased to thirty. They affect various shapes, but yet retain a single and common feature—that of an iron plate worn beneath by friction. This character was so striking, that, among others, one of our able confrères who superintends the archæological museum of the town, was looking out every day for some proof as to the use of these hippo-sandals. One of these objects was at last brought to him, having two wings bent over towards each other (fig. 128), in an acute arch, and exactly representing the foot of an ox to which it had been moulded by the hammer and wear. There could be no doubt about it; M. Vuilleret had in his hands a shoe adapted for the bovine species; he had solved the problem. I carried this article to the farriers' shops in the suburbs, where oxen are usually shod, although after a different fashion. "This," said a workman at the first glance, "is a bullock's shoe." "This object," the farmers present generally assented, "would not be worn by an ox at work or at pasture; it would confine their movements too much. But if a convoy of oxen or cows was sent along the roads, it might be of the greatest utility; for there is always in a travelling drove animals whose feet are wounded, and for whom it is necessary to have recourse to temporary shoeing." This last explanation put us on the alert in comprehending the diversity in shape of the specimens in the museum; and M. Vuilleret was not long in showing us shoes made for the single claw of the ox (fig. 129), and yet belonging to this class of pretended hippo-sandals. . . . . whose name it behoves us to rectify . . . . . it should be bu-sandal.' It appears to have been forgotten that a bisulcus or cloven-footed animal cannot travel easily with its digits restrained by a solid plate with two iron bands compressing them on each side. And we may ask if the experiment was tried of making oxen walk for a mile or two with any of these Besançon specimens? None of those I have examined would fit the foot of an ox, and there is no reason to suppose that they were ever used for that purpose by the Romans. I have already noted that tips of iron, conjectured to have armed the feet of cattle, were recently found at Pompeii. Until I have inspected these articles, or seen drawings of them, I cannot decide as to their having been so employed, though I think it improbable, as Cato the Censor (B.C. 160) speaks of the application of liquid pitch to the under surface of the hoofs of oxen to preserve them from wear, as is now done in the East with the feet of elephants and camels: 'Boves ne pedes subterant, priusquam in viam quoquam ages, pice liquidam cornua infima unguito.'[34]

It will then, I think, be admitted that these strange-looking iron plates are not horse, mule, or ox sandals, and that they could not be employed as such. The form and situation of the clips and hooks alone forbid such a supposition, and the Romans would indeed deserve to be classed among the most clumsy of all contrivers if they ever attempted to put such a garniture on their horses', mules', or oxen's feet, even supposing they were ignorant of nail-shoeing, which at the time these were made it appears they were not.

If not supports for lamps, ancient stirrups, sandals for sound or diseased feet, or iron socks for wearing at night while the horses were resting, what then are they? The first one I saw in the British Museum—belonging to the second class—suggested its probable use. Was it not a skid or drag (sabot or enrayeur) to put under the wheel of a carriage to moderate its descent on steep places? This appeared to me a very likely supposition. It is well known that the Romans employed such instruments for their vehicles, and they are often mentioned in their real, as well as in a figurative, sense, by the designation of 'sufflamen.' For instance, Juvenal, in the ist century, in his eighth satire (148), writes:Ipse rotam astringit multo sufflamine Consul.

Nec res atteritur longo sufflamine litis.

Tardat sufflamine currum.

Ainsworth, in his Latin Dictionary, explains the meaning of the designation: Sufflamen. Sufflo, machinæ genus, quo in descendu vel procursu nimio tota solet sufflari, i. e., retineri. And another classical dictionary explains it as 'lignum illud, quo per radios rotarum trajecto; vel ferreum instrumentum in modum soleæ formatum, quo subter notæ unius canthum supposito, currus in declivibus locis nimio impetu ruentes cohibentur: illud Itali stanga, hoc scarpa vocant.

There can be no doubt, then, as to the Romans possessing such an instrument to facilitate the travelling of their carriages; but I do not remember any mention being made as to their discovery anywhere; and in all likelihood we have them here. I am aware that in a sepulchral bas-relief found at Langres, representing, among other objects, a cart drawn by three horses, two chains are seen attached to the body of the carriage, and in front of the hind wheel, one with a ring, the other with a hook at the end to lock round the felloe between two of the spokes, and make a fetter for the wheel. So says Mr Rich; but this kind of contrivance would, one is inclined to think, be of as limited application in the Romano-Gallic days as now. It is a most expensive way of staying the velocity of a carriage. The shape of the supposed sandals presents but little difference from that of the skid or wheel-shoe of now-a-days, except, perhaps, in length.

The drawing of one of those attached to the waggons of the Military Train will make this manifest (fig. 137).

fig. 137

- ↑ Le Tombeau de Childéric I.

- ↑ Public, de la Soc. Archéol. du Luxemburg, vols. vii. p. 185 xi. p. 92.

- ↑ Collect. Antiq., vol. iii. p. 129.

- ↑ Journal Vét. de Belgique, 1853.

- ↑ Annales de Méd. Vétérinaire, 1867.

- ↑ Journal Vét. de Belgique, 1853.

- ↑ Journal de Méd. Vétérinaire de Lyon, 1857.

- ↑ Journal de Méd. Vét. Militaire, 1866.

- ↑ Megnin. Origine de la Ferrure.

- ↑ Catalogue of the Museum of London Antiquities, p. 77.

- ↑ Schmidt. Recueil d'Antiq. trouvé â Avenches, Culon, etc. Berlin, 1780.

- ↑ Public, de la Soc. pour le Recher. des Monumens Luxembourg, vol. vii.

- ↑ Journal Vétérinaire de Belgique, p. 30, 1853.

- ↑ Op. cit. vol. ix.

- ↑ Op. cit vol. xi.

- ↑ Journal de Med.Vétérinaire, 1853.

- ↑ Journal de Méd. Vét. de Lyon, p. 241, 1857.

- ↑ 'Je le declare franchement, j'ai quelque peine à accepter cette assertion, toute positive qu'elle paraît. La raison principale, c'est que M. de Widranges n'a pas vu lui-même le fait qu'il raconte; qu'il le tient d'ouvriers toujours disposés à en iniposer ou à se faire illusion à euxmêmes, et enfin, parce que notre expérience nous a montré combien il est difficile que le pied du cheval se soit suffisamnient conservé pour être aussi bien restitué, même par I'homme le plus compétent. Quoique M. de Widranges soit un fort honnête et trés-consciencieux archéologue, je lui demanderai la permission de citer, sous sa seule responsabilité, les faits qui précédent, faits dont I'lmportance est d'autant plus grand que jusqu'ici, en France, ils sont seuls de leur genre.'—Le Tombeau de Chihléric, p. 154.

- ↑ La Maréchalerie Française, p. 40. Paris, 1867.

- ↑ Mémoires de la Soc. d'Emulation du Doubs, 1864.

- ↑ La Seine Inférieure, Hist, et Archaeol. Paris, 1864.

- ↑ Catalogue of the Museum of London Antiquities, p. 77, 1854. Collectanea Antiqua, vol. iii. p. 128.

- ↑ Op. cit. p. 13.

- ↑ Grivaud de la Viucelle. Arts et Métiers des Anciens.

- ↑ Cachet. Le Tombeau de Childérie, p. 164, note.

- ↑ Pub. de la Soc. Arch, de Luxembourg, vol. xii. p. 163.

- ↑ C. R. Smith. Illustrations of Roman London, p. 146.

- ↑ Letters from Holland.

- ↑ Recueil d' Antiquitiés Suisses, p. 30.

- ↑ Op. cit. p. 163.

- ↑ Mem. de la Soc. d'Emulation du Doubs, p. 132, 1863.

- ↑ Journal de Méd. Vét. Militaire, vol. iv. p. 163.

- ↑ Mem. de la Soc. d'Emulation du Doubs, p. 143, 1864.

- ↑ De Re Rustica, cap. 72.