XXV.

THE VINTAGE SEASON, AND MONTEREY.

I.

It was the pleasant vintage season at San José. Santa Clara County, of which San José is the capital, boasts of a number of acres of grape-vines under cultivation (over eleven thousand) second only to Sonoma County. Napa, however, to the north, and Los Angeles, to the South, greatly surpass it in gallons of wine and brandy produced.

I visited, among others, the Le Franc vineyard, which dates from 1851, and is the pioneer in making wine-growing a regular industry. Here are about a hundred and seventy-five thousand vines, set out a thousand, perhaps, to the acre. The large, cheerful farm buildings are upon a gentle rise of ground above the area of vines, which is nearly level. An Alsacian foreman showed us through the wine-cellars. A servant-maid bustling about the yard was a thorough French peasant, only lacking the wooden shoes. The long tables, set for the forty hands employed in the vintage-time, were spread with viands in the French fashion. Scarcely a word of English was spoken.

At other places the surroundings are as exclusively Italian or Portuguese. One feels very much abroad in such scenes on American soil. The foreigners from

Southern Europe take naturally to wine-making and go

into it, from the few hundred gallons of red wine made by the Portuguese and Italian laborers for their own families, to the manufacture of an American champagne on a large scale by the Hungarian, Arpad Haraszthy, at San Francisco. The Americans, who have not acquired the habit of looking upon wine as a necessity in the family, are not yet, as a rule, very active in its production.

A certain romantic interest attaches to this ancient industry. The great tuns in the wine-cellars and all the processes were very clean. It was re-assuring to see the pure juice of the grape poured out in such floods, and to feel that here was no need—founded on scarcity, at least—for adulteration.

Teeming loads of the purple fruit were driven up, and across a weighing scale. The contents are lifted to an upper story, put into a hopper, where the stems come off, and the grapes fall through to a crusher. They are lightly crushed at first. It is something of a discovery that the earliest product of grapes of every hue is white wine. The red wine gets its hue from the coloring matter in the skins, which are utilized in a subsequent ruder squeezing.

I shall not enter upon all the various processes—the racking off, clarifying, and the like—though, so much in the company of those who spoke with authority and were continually holding up little glasses to the light with a gusto, like figures in popular chromos, I consider myself to yield in knowledge of such abstruse matters to few. Immense upright casks, containing a warm, audibly fermenting mass, and others lying down, neatly varnished, with concave ends, are the most salient features in the dimly lighted wine-cellars.

They are not cellars, properly so called, either, since

BOTTLING CHAMPAGNE AT SAN FRANCISCO.

large scale, the cobwebs have been allowed to increase and hang like tattered banners. Through these the light penetrates dimly from above, or with a white glare from a latticed window, upon which the patterns of vine-leaves without are defined. The buildings are brown, gray, and vine-clad, with quaint, Dutch-pavilion-looking roofs, and dove-cotes attached. A lofty water-tank, with a wind-mill a feature of every California rural homestead here is more tower-like than usual.

Round about extend long avenues of eucalyptus, pine, tamarind, with its black, dry pods; the pepper-tree, with its scarlet berries; large clumps of the nopal cactus, and an occasional maguey, or century-plant. All is glowing now with the tints of autumn. Poplar and cottonwood are yellow. The peach and almond, the Lawton black-berry, and the vineyards themselves, touched by frost, supply the scarlet and crimson. The country seems bathed in a fixed sunshine, or in hues of its own wines.

The vines, themselves short and stout, and needing no support, yield each an incredible number of purple clusters, all growing from the top. They quaintly suggest the uncouth little men of Hendrik Hudson who stagger up the mountain, in "Rip Van Winkle," with kegs of spirits on their shoulders.

No especial attention is given to the frosts now, but those of the early spring are the object of many precautions. The most effectual is to kindle smudge-fires about the vineyard toward four o'clock in the morning, the smoke of which envelops it and keeps it in a warmer atmosphere of its own till the sun be well risen.

Three to four tons of grapes to the acre are counted

A BRANDY CELLAR, SAN JOSÉ .

in quality. The best results, we were told, are got from such vines as the Mataro, Carignane, and Grenache, imported cuttings from the French slope of the Pyrenees. There were at Le Franc's not less than sixty varieties, under probation, many of which will, no doubt, give an excellent , account of themselves. They are assembled from Greece, Italy, Palestine, and the Canary Islands, so that we have all the chances of the development of something suited to our peculiar conditions.

II.

I left San José to drive along the dry, shallow bed of the Guadalupe River to the Guadalupe Quicksilver Mine, a more remote and less visited companion of well-known

New Almaden. The mine is in a lovely little vale, with a settlement of Mexican and Chinese boarding-houses clustered around it. Some bold ledges of rock jut out above, and a superintendent's house surrounded by flowers hangs upon the hill-side. A weird-looking flume conveys

the sulphurous acid from the calcining furnaces to a hill-top, upon which every trace of vegetation has been blasted

by its poisonous exhalations.

Then I made a little tour by rail southward through the immense "Murphy" and "Miller and Lux" ranches, comprising a grain country as flat as a floor.

We turned west through the fertile little Pajaro Valley, the emporium of which for produce, and fine red-wood lumber, cut in great quantities on the adjoining Santa Cruz Mountains, is the thriving town of Watsonville. We ran along a rugged coast, past wooded gorges and white sea-side cottages, at Aptos and Soquel, to the much-frequented resort of Santa Cruz. Santa Cruz has bold variations of level, the usual commonplace buildings, a noble drive along cliffs eaten into a hundred fantastic

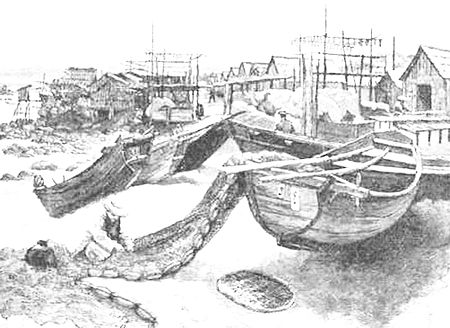

A BIT OF OLD MONTEREY.

shapes by the waves, and shops for the sale of shells, and its summer boarders, who become, with change of seasons, winter boarders in turn. Thence finally to the long-anticipated Monterey.

Here at last was something to commend from the point of view of the picturesque without reservation. Monterey has a population which still, in considerable part, speaks Spanish only. It retains the impress of the Spanish domination, and little else. When you are told in your own country that somebody does not speak English, you naturally infer that it is brokenly, or only a little, But at Monterey it means absolutely not a word. There are Spanish signs on the shops, and even Spanish advertisements, as, for instance, the Wheeler & Wilson Maquinas á Coser, on the fences.

My Mexican experience was a liberal education for Monterey, and I made the most of it. I was taken to call upon an ancient señorita, in whose history there was some romance.

"Las rosas son muy secas"—("The roses are very dry") she said very apologetically, as we entered her little garden, laid out in regular parallelograms, behind an adobe wall topped with red tiles. Large yellow and red roses were blowing to pieces in the wind before her long, low adobe house.

She was one of those who spoke no English. It seems if there were some wilful perversity in it, after having been since 1846 a part of the most bustling State of most active country in the world. It seems as if it must be some lingering hatred of the American. But the señorita is a little, thin old lady of fifty. Her romance was with an American officer, it is said, thirty years ago, and she has never since married, but has withered, like her roses, at Monterey.

As seen from a distance, scattered loosely and white on the forest-crested slope of the fine bay, the little city, which has now perhaps two thousand inhabitants, does not show its unlikeness to other places. But when entered it consists almost exclusively of whitewashed adobe houses, and the straggling, mud-colored walls of enclosures, for animals, known as "corrals." Many of them are vacant. At frequent intervals is encountered too some abandoned old barracks, or government house, or military prison of historic fame, with its whitewash gone, holes in its walls, and bits of broken grating and balcony hanging aimlessly on, waiting only the first opportunity to let go.

LOOK OUT STATION.

The travellers of my youth had a fashion of talking glibly of adobe, without explaining what adobe was. Let me not be guilty of the same error. Adobe is bricks made of about twice the usual size, and dried in the sun instead of being baked. Walls are made of great thick-

ness, in order that, though outside and inside crumble off, there may be a good deal left. Like a number of other things, it stands very well while not assailed; and in this climate it is rarely assailed by violent extremes of temperature.

The typical adobe house of the best class is stuccoed and whitewashed. It is large on the ground, two stories in height, and has verandas. Again, it is of but one story, with an interior court-yard. It has green doors and shutters, and green, turned posts, in what we now call the "Queen Anne style," and it is comfortable and home-like to look at.

One of them contains the first piano ever introduced into California, and the owners are people who made haste to sell out their all at San Francisco and invest it here, in order to reap the greater prosperity which was thought to be waiting upon Monterey. Two old iron guns stand planted as posts at the corners of the dwelling. In front of others are some walks neatly made of the verterbræ of whales, taken by the Monterey Whaling Company. The company is a band of hardy, weather-beaten men, chiefly Portuguese, of the Azores, who have a lookout station on the hill by the ruined fort, and a barracks lower down. They pursue their avocation from the shore in boats, with plenty of adventure and no small profit.

Monterey, which is now not even a county seat, was the Spanish capital of the province from the time it was thought necessary to have a capital. The missionary father, Junipero Serra, came here from Mexico in the year 1770. It was next a Mexican capital under eleven successive governors. Then it became the American capital, the first port of entry, the scene of the first Constitutional Convention of the State, and an outfitting point for the southern mines. Money in those early days was so

CUTTING UP THE WHALE.

store-keepers hardly stopped to count it, but threw it under the counter in bushelfuls.

A secret belief in the ultimate revival of Monterey seems always to survive in certain quarters, like that in the reappearance of Barbarossa from the Kylfhäuser Berg, or the restoration of the Jews. Breakwaters have been ambitiously talked of, and it is said that the bay could be made a harbor and shipping-point and the rival of San Francisco.

The only step toward such revival as yet is a fine hotel, built by the Southern Pacific railroad, which may make it, instead of Santa Cruz, across the Bay, the leading sea-side resort. Though not so grandiose a direction as some others, this is really the one in which the peculiar conditions of the old capital are most likely to tell. The summer boarder can get a tangible pleasure out of its historic remains and traditions of greatness, though they be good for nothing else. The Hotel del Monte is a beautiful edifice, not surpassed at any of our American watering-places, and unequalled in the charming groves of live-oak and pine and profusion of cultivated flowers by which it is surrounded, and the air of comfort combined with its elegant arrangements.

This is the way with our friends of the Pacific coast. If they do not always stop to follow Eastern ideas and patterns, when they really attempt something in the same line, they are as likely as not to do it a great deal better.

The climate at Monterey, according to statistical tables, is remarkably even. The mean temperature is 52° in January and 58 in July. This strikes one as rather cool for bathing, but the mode is to bathe in the tanks of a large bath-house, to which sea-water is introduced, artificially warmed, instead of in the sea itself.

THE HOTEL DEL MONTE - MONTEREY

CLIFFS AND FOREST AT MONTEREY.

In other respects the place seems nearly as desirable at one time of the year as another. The quaint town is always there; and the wild rocks, with their gossiping gulls and pelicans; and the drives through the extensive forests. There are varieties of pine and cypress the latter like the Italian stone-pine peculiar to Monterey.

The more venerable trees, hoary with age and hanging moss, are contorted into all the fantastic shapes of Doré's "Inferno." They grow by preference on the most savage points of rock, and the wild breakers toss handfuls of spray up to them high in the air, in amity and greeting.

Along the beach on this far-away point of the Pacific Ocean we find a Chinese fishing settlement. Veritable Celestials, without a word of English among them, have pasted the usual crimson papers of hieroglyphics on shanty residences. They burn tapers before their gods on the rocks, and fish for a living in just such junks and small boats as may be seen at Hong-Kong and Canton. They prepare avallonia meat and avallonia shells for their home market. One had rather thought of the Chinese element as confined to San Francisco alone, but it is a feature of quaint interest throughout all of Southern California.

At Monterey is found an old mission of the delightfully ruinous sort. It is in the little Carmel Valley, which is bare and brown again, after the green woods are passed, four miles from the town. The mission fathers once had here ninety thousand cattle, and other things to correspond. There are now only some vestiges, resembling earth-works, of their extensive adobe walls, and, on a rise overlooking the sea, the yellowish, low, rococo church of San Carlos.

The Mexican traditions in design and proportion accompanied them here, but the workmanship as they went farther from home became curiously rude, and speaks of the disadvantages under which it was done. A dome of concrete on the bell-tower is unequally bulged; a star window in the front has very irregular points. The interior does not yield, as a picture of sentimental ruin, to Muckross Abbey or any broken temple of the Roman Campagna. The roof, open now to the sky, with grasses and

CHINESE FISHING VILLAGE.

SAN CARLOS'S-DAY AT THE OLD MISSION.

There are grasses growing within, sculptured stones tumbled down, vestiges of a tile pavement, tombs, bits of fresco, and over all the autograph scribblings of a

myriad of A. B. Smiths and J. B. Joneses, visitors here in their time like ourselves.

DRYING FISH AT CHINESE VILLAGE.