III

UP THE LONG MOUNTAIN SLOPE.

I.

There is but one train a day, each way, on the English railway, and the journey occupies twenty hours. The road is a great piece of engineering, and has been described more than anything else in Mexico. Photographs—almost the only good ones to be had in the country—are plentiful, displaying its notable points. It climbs seven thousand six hundred feet to the table-land in a distance of about two hundred miles, the whole way to the capital being about two hundred and sixty. It has the transporting of the greater amount of construction material brought into the country for the new roads, and has lately been quite profitable. A first-class fare is $16;

a second-class, $12.50; and baggage is charged for, as on the Continent of Europe.

Behold us at last at the station, at eleven o'clock at night, ready to climb to the capital—but how unlike our great predecessor, Cortez—by railway. No, indeed; poor hero! he had to linger at the coast for months before beginning his long and painful march, with a battle at

every step. Nor was it by the same route. He went in by Tlaxcala, Cholula, Puebla, and so over between the great snow-peaks of Popocatepetl and Ixtacihuatl (the

White Woman), down to the gleaming lakes and palaces

MAP OF ENGLISH RAILROAD FROM VERA CRUZ TO MEXICO.

I say beautiful Jalapa—although I have not been there myself—because all testimonies point with such a unanimity to the charms of soil and climate, and the beauty of the feminine type, in what is considered a peculiarly favored spot, that I think there can be no doubt about it.

There were no sleeping-cars; but the carriages, divided into compartments for eight, and comfortably padded (on the European plan), filled their place very well. The passengers in the third-class cars had already begun the night with a boisterous singing and playing of harmonicas. To-morrow was the Sabado de Gloria (or Holy Saturday), an occasion of merry-making, and they were taking an earnest of it. A car containing half a company of dusky Indian soldiers, who act as an escort, was coupled on to the train.

The associates in the compartment in which I established myself were the French engineer sent out to report for principals in Paris on Mexican mines, and the young Frenchman bringing back a bride from his own country. All at once there entered it so lawless and bizarre-looking a figure that the French engineer sent out to report on mines to his principals in Paris thought it prudent to descend hastily and seek quarters elsewhere. The rest of us, though remaining, were, perhaps, in no small trepidation. It was the first view at close quarters of a dashing type of Mexican costume and aspect which is peculiarly national.

Our new friend was dressed in a short black jacket, under which showed a navy revolver, in a sash; tight pantaloons, adorned up and down with rows of silver coins; a great felt sombrero, bordered and encircled with silver braid; and a red handkerchief knotted around his neck. A person in such a hat seemed capable of anything. And I had forgotten to mention silver spurs, weighing a pound or two each, upon boots with exaggerated high and narrow heels. This last, by-the-way, is a peculiarity of all boots and shoes in the market, which aim thus, it would seem, to continue the old Castilian tradition of a high instep.

Would it be his plan to overawe us with his huge revolver, alone?

Or would he, at a preconcerted signal, be joined by confederates from the third-class car or a way-station, who would assist him to slaughter us?

The traveller is rare who arrives in Mexico for the first time without a head full of stories of violence. The numerous revolutions, the confused intelligence which reaches us from the country, give a color to anything of the kind; and the stories retain their hold for a time even in the most frequented precincts.

We got under way. The new arrival, instead of devouring us, proved the most amiable of persons, and we were soon upon excellent terms with him. He was a wealthy young hacendado, or planter, returning to estates of his, on which he said six hundred hands were employed. He offered cigars, gave us details in answer

to our eager curiosity about his novel dress; and we had shortly even tried

on—bride and all—the formidable sombrero, and learned that the price of such an one in the market is from $20 to $30. The silver-bound sombrero, and ornaments of coins, are a favorite kind of Mexican extravagance even among the lower classes,

which is perhaps accounted for by the lack of proper places of deposit for savings in other forms.

II.

It was moonlight. Sleep on such a night was out of the question. Not a foot of the scenery ought to be lost. But the padded coach was comfortable; the fatigues of the day had been severe. The lively conversation became fitful, then lapsed into long silences. The events of that first night, half dozing, half waking, sometimes even alighting at the little stations, seem wholly like a

dream—the waking part, if possible, stranger than the other.

Palms and bananas and dense coffee shrubbery, with hamlets of thatched cottages sleeping peacefully among them; a glimpse of a cataract; an Indian mother singing to her baby; perfumes coming in at the window; statuesque, silent men in blankets, and Moorish-looking women, offering fruits; stations from the outer doors of which, when reached, no town was visible, but only an immense darkness; persons taking coffee in lighted interiors; the dusky soldiers laughing loud in their compartment; a few startling words of English, sometimes with a Southern or even Hibernian accent, spoken by imported employes of the line meeting to exchange a comment, generally unfavorable, on their situation—these are the impressions that stamp themselves upon the memory.

As soon as the first gray of daylight appears it seems incumbent on us to begin to admire the country. We are not far past Cordoba, the centre of its most important coffee-growing interest.

"Pouf!" says our friend, the hacendado, with an air of disdain. He will not take the trouble to look out of the window. He expects things very much better. We have, in fact, passed remarkable scenes in the night, but the best is still before us, and presently begins.

At a little station called Fortin we commence to wind along the side of one of the vast sudden gorges which impede travel in the country, the barranca of Metlac. There are horseshoe curves which almost permit the traditional feat in which the brakeman of the rear car is said to light his pipe at the locomotive. We pass tunnels and trestle bridges, see our route above and below us on the hills in such varied ways that it is hardly possible to understand that these are not so many different roads instead of the same. There is a point above Maltrata, distant but two and a half miles in a direct line, which must be reached by twenty miles of zigzag.

The history of this road, from the political point of view, presents hardly fewer obstacles and vicissitudes than those opposed by nature to its engineers. It has passed, in its time, under the rule of forty different presidencies, and lost and recovered its charter in the revolutions. Though of so moderate length it required over thirty years and $30,000,000 to build it.

The passengers ran out at the small stations for flowers, with which we adorned ourselves. So, too, wreaths were hung about the neck of Cortez's horse in his progress, and a chaplet of roses upon his helmet. We gave the new bride heliotrope, roses, jasmine, and the splendid large scarlet flower—the tulipan—which may pass for the type of tropical beauty.

The sun came up and lighted Orizaba, rising 17,375 feet beside us to the right, making it first rosy-red, then golden. The peak is a perfect sugar-loaf in form, with nothing splintered and savage about it, as in Switzerland. It seems almost too tame at first—a sort of drawing-master's mountain—and, above the tropical landscape, is like snow in sherbet. The city of Orizaba is an important small place, the scene of a dashing surprise of the Mexicans by the French, at the hill of El Borrego. It has charming torrents, which furnish water-power for cotton and paper mills. One of these torrents, conveyed in an arched aqueduct, turns the machinery of the ingenio, or sugar plantation, of Jalapilla, once a country residence of Maximilian.

A delegation of relatives had come down the night before to await our young couple here. What embracing and chattering! A Mexican embrace has a character of its own. The parties fall upon each other's necks, as we are accustomed to see done on the stage. It is given, too, between mere acquaintances, almost as commonly as shaking hands.

A vivacious sister-in-law aimed to give the new-comer an idea of what was before her in her future home.

"Such flowers as I have in the court-yard!" she said, raising her eyes, with an expressive gesture; "such oranges, camellias, azaleas! Ah yes, indeed, I believe it well."

"And Jack?" inquired the husband, addressed as Prosper; "how always goes poor Jack?"

"Ah! he is dead," replied the vivacious sister-in-law.

"I regret to tell you, but so it is."

It appeared that Jack was a favorite monkey, and for a moment his untimely fate cast a certain gloom over the

company.

III.

From the heights where we were little villages, with squares of cultivated fields around them, were seen at vast distances below, with the effect of those miniature topographical preparations in relief displayed at international

exhibitions.

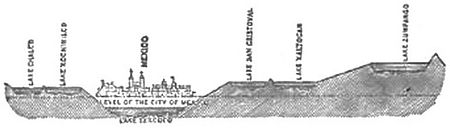

It greatly simplifies Mexico to remember that, in profile, it is a long, continuous mountain-slope, rising from the Atlantic to a central table-land, and falling, though more gradually, on the other side to the Pacific. Along the ascents, as well as at the top, are some benches, or level breathing-places. These table-lands are the chief seats of population, and they are utilized as much as possible for the lines of the north and south railways.

TRANSCONTINENTAL PROFILE OF MEXICO.

This steep formation accounts for absence of navigable streams and for the existence of climates verging from tropical to temperate, nearly side by side. The sharpness of contrasts in climate is scarcely to be appreciated by the hasty voyager. The really tropical vegetation is succeeded by a kind which to the eye of the American of the North is quite as exotic. Banana and cocoa-nut are followed by a hardy kind of fan-palm; by nopal, or prickly-pear, as large as the apple-tree with us; by the tall, straight organ-cactus, in use for hedges; and the remarkable maguey, or century-plant.

What would not some of our American conservatories or a certain well-known New York club give for some of these splendid specimens! The spiky maguey, like a sheaf of sword-blades, grows eight and ten feet high. It is the typical production of the central table-land. Its

sap furnishes in extraordinary quantities the beverage called pulque—the wine of the country. From it, in addition, are made thatch, fuel, rope, paper, and even stuffs for wearing apparel.

Our third-class passengers celebrated their Sabado de Gloria with great spirit, by shouting, and firing pistols and Chinese crackers from the car windows. Teams of mules, with their load, whatever it might be, gayly adorned, showed that it was being equally observed in the country. It is a day devoted by custom to the particular abasement of Judas, who is treated as a kind of Guy Fawkes and dishonored in effigy. Venders parade the streets with grotesque images of him, and children at this time estimate their fortune in the number of Judases they possess, just as at the season of All-Souls it is in cakes, gingerbread, and even more substantial viands, fashioned into death's-heads, cross-bones, and coffins.

At Apizaco, the junction of a branch-road to Puebla, we met a merry excursion, decorated with rosettes and streamers. It had two mammoth Judases, stuffed with fire-works, one on the locomotive, the other on a baggage-car. The former was blown up, as a kind of compliment to us by way of exchange of ceremonies with our own train, amid hilarious uproar.

We had now entered upon the central table-land of Mexico. Long, dotted, perspective lines of maize and maguey stretched to distant volcanic-looking hills. A few laborers in white cotton were ploughing with wooden ploughs, after the pattern of the ancient Egyptians.

At the stations squads of a mounted rural police, in buff leather uniforms and crimson sashes, which give them a certain resemblance to Cromwell's troopers, salute the train,

The sparse towns consist of a nucleus of excellently built old churches amid an environment of mud-colored habitations. They are in crying need of whitewash.

Will they ever get it?

The face of the country was not the verdant paradise that may have been expected, but parched and brown.

A RAILWAY JUDAS.

We had come at the end of the rainy season. Small columns of dust, whirling like water-spouts, were a constant feature of the landscape. A stage-coach going along a distant road was marked by its own dust, as a locomotive by its smoke.

Isolated houses there were none, with the exception of (at long intervals) some gloomy, square, fort-like hacienda, with straw-stacks and flocks and herds near it.

Indian peasants offered for sale, all along the way, cakes spiced with green and red peppers. The village of Apam is the centre and Bordelais of the pulque industry. The new-comer here usually makes his first trial of that beverage, milk-like in aspect, but somewhat viscid and sour to the taste, with heady properties. It does not commend itself to favor on a first acquaintance. Wry and contemptuous grimaces are made over it, but in time, as occurred in my own case, it may become very palatable, as it is said to be healthful. It is poured into little earthen pitchers from bags of whole

sheep-skins, with the wool-side in, like the wine-skins of the East and "Don

Quixote." These bags, resembling dressed pigs, lie about on the ground or the freight-car, with their legs dumbly kicking up in the air, in many a grotesque attitude.

But one glimpse of real Aztec antiquity along the way, and that at San Juan Teotihuacan, thirty miles from the capital. The deceptive shapes of the hills, which assume symmetrical forms, had frequently produced a throb of half self-delusion, but here are two genuine pagan teocallis, pyramids dedicated to the sun and moon, and a great area covered with broken fragments and vestiges of tombs. It is thought to have been old and ruined even in the time of the Aztecs. Children offer at the train caritas, as they call them ("little faces"), and other fragments of earthen-ware together with occasional pots and idols of large size, which they represent as having been dug up out of the soil. They have certainly been buried in the soil; but later, finding that the manufacture of spurious antiquities is a thriving industry, one takes leave to question for what length of time.

And yet, what can it matter? These ancient-seeming jars, with their symbols and images of the war-god and what not upon them, are at least unique and historically correct. One does well to bring home what he can get, for default of better, and not ask too many questions.

San Juan is a place that one mentally makes a note of as to be returned to; and I spent some pleasant days there later, poking among the potsherds of the past, and picking up ordinary caritas and bits of flint weapons, for myself.

IV.

But no dallying now. The shades of evening draw on. We are weary and travel-stained with the twenty hours' journey and the many excitements of the day; but

the great moment is at hand. Gleams of distant water, thickets of maguey and cacti, with a "peasant stealing mysteriously among them, behind a troop of donkeys! The geography picture is realized to the life. The water comes nearer; we skirt its borders. Can it be that these lonesome, shallow expanses, without vestige of sail or even skiff, their muddy shores white with a deposit of salt and alkali—can it be that these are the great lakes of Tenochtitlan, on which Cortez launched his brigantines? And the famous floating gardens, where are they? All in good time! We shall see. The sacred hill of the Virgin of Guadalupe, with a cluster of interesting-looking churches upon it, is passed. Remains of ruined haciendas and fortifications, and dilapidated adobe hovels, appear. We run out upon a long, low causeway, skirted by the arches of an aqueduct, over marshes. Other similar causeways are seen converging from a distance. One had not expected to find everything so unrelievedly flat. It is like climbing the mountain to find the Louisiana lowlands. A chain of yet higher mountains surrounds it, it is true; the snowy summits of Popocatepetl and its mate, the White Woman, always shine upon it from a

distance, but Mexico itself is a basin. It has been under water, and would be yet, but for artificial works by which the lakes have been made to recede and left behind them these alkali-whitened margins.

It is a disillusionment very like that of approaching Venice at low tide.