IV

The Work and the Artistic Theory of Millet

Relatively speaking, Millet produced little. He began to exhibit in 1840 and did not cease work until his death, that is for more than thirty years. Yet he left only about eighty pictures, nearly all—with a few exceptions, such as the Woman shearing Sheep—of small dimensions. The reason is that, though he brought much fire and energy to bear in painting certain works, he generally spent much time in meditation, often began again and was seldom satisfied. His nature was one of the least complex imaginable; his was a soul all of one piece, in which feelings, ideas, and the vision of external things did not vary from the beginning of his life to the end. He felt this inclination of his mind to repeat itself, and was not the man to fix himself in a formula. Therefore he never ceased working to enlarge his thought and to enrich and vary his technical methods. He even tried for some years, not without success, to engage in paths remote from his real vocation. Then he perceived that he was going the wrong way and consented to remain within the limits of his nature, never, however, relaxing his efforts to improve every part of his artistic domain and to penetrate more deeply into the spirit of the things and beings that he observed.

Let us endeavour to sum up this evolution. His first works have not been preserved to us, but the choice of subjects and the reminiscences left by contemporaries testify clearly to the unity of his life. From his very beginning as a painter his two sources of inspiration, his two models, are the natural scenes of daily life and the Scriptures. One of his earliest drawings represents an old man bent double, broken by age and sufferings. Of the two drawings which he brought to the Cherbourg teacher, one was an illustration of St Luke and one a pastoral scene. Under Delaroche he conscientiously applied himself to draw from the Holy Family of Francis the First and from the antique; but beneath the academic garb that he assumed, his heavy and violent peasant temperament was always breaking out. His companions used to joke about his figures "in the fashions of Caen," and he wearied those around him by his admiration for Michael Angelo. Then poverty compelled him to make imitations of the fashionable painters of the eighteenth century, whom he could not bear. This compulsion had at least the advantage that it taught him the mastery of his brush; he freed himself from Delaroche's blacks and opaque shadows; he studied Correggio; and so successful were his endeavours to acquire those qualities wherein he chiefly fell short that by about 1844 his most striking quality in the eyes of his contemporaries was his colour. He had charming flower-like tones of grey and pink. He painted easily and he pleased. The best example of his works of this period is the Portrait of little Antoinette Feuardent at six years old. Her head is covered by a pink silk kerchief; she is kneeling barefooted before a looking-glass, looking at herself and making little grimaces. In the year after his second marriage up to about 1847 he had an exuberance of sensuous spontaneous ardour, very unusual with him, which showed itself in Bacchantes, in mythological canvases and Offerings to Pan, amorous idylls that are yet simple and innocent. He worked on and on at the improvement of his qualities of form; and having in the previous years rather neglected correctness of drawing in his pursuit of colour, he set himself in his Oedipus unfastened from the Tree to make a perfect study of the nude. But all these were but trials which could neither permanently nor successfully deceive others nor himself as to his true nature; nature breaks through these disguises and discerning judges were not blinded by them. Gautier and Thoré noted, even in the Oedipus, a barbaric energy that vainly attempted to conceal itself beneath academic frigidity. Diaz said of the Women Bathing that they "came out of a stable," and Millet, although wounded by this speech which failed to recognise the rustic and half heroic grandeur perceptible even in these Women Bathing, felt well enough that he was out of his element in this world of fine conventions and was ashamed to see himself in it. He shared to some degree the feeling of Paul Huet, who said that when he saw his pictures in exhibitions beside "alarmingly clean Parisian canvases, he felt like a man with muddy shoes in a drawing-room." To console himself for these untruthful works he studied the workman types of Paris and the country round Paris, and prefaced his great rustic pictures by The Winnower in 1848.

Finally he broke sharply with all fashionable art and in 1849 gave himself up definitely to studying the country. Into this pursuit he threw himself with enthusiastic ardour. Every day during the early part of his residence at Barbizon, and sometimes in a couple of hours, he would paint a rustic scene; and in a letter to Sensier dated 1849 he says that he has five pictures finished and three more in hand. The first Sower of 1850 was painted in so furious an impulse that Millet presently found his canvas too short and had to repaint the figure, tracing the outline. The works of this first Barbizon period are distinguished by their violence and heavy execution. Gautier who, speaking of the Winnower, had pointed out to Millet, as early as 1848, the thickness of his impasto, says that all these canvases are "as rugged as shagreen leather."

Millet himself was not satisfied, but his self-criticism differed from that of his critics; he was anxious not to decrease, but on the contrary to accentuate, the harshness of his manner, and did not yet consider his way of painting strong enough. He wrote in 1853: "I seem to myself like a man who sings true but with a weak voice and who is hardly heard." He was helped by the advice of Rousseau, with whom he had become intimate, and with whom he had at this time some idea of collaborating, as some letters remain to testify.[1] Exposed thus to a powerful influence that strengthened the natural development of his genius, his manner broadened; about 1856 the landscape began to assume more importance, and he arrived at the style of the Gleaners and The Angelus, a style that was concentrated, sober, simple, austere—his enemies said poverty-stricken,—because he tried to efface himself behind his subject.

The rejection of Death and the Woodcutter in 1859 awoke his combative instincts, and he answered it in 1862-63 by the challenge of the Man with a hoe, in which he made a clean sweep of everything that could possibly please, and displayed his roughness absolutely bare. It was, as he said himself, the sheer "cry of the earth" in all its savage reality.

This almost excessive affirmation of his individuality eased him; and, moved less by the criticisms which his work aroused than by the secret objections which his own taste raised against this passionate exaggeration of his style, he immediately went, in the impulse of reaction, to the other extreme. He wished to paint mythological pictures and illustrate Greek idylls. This, too, was the moment at which he made some decorative paintings. Though some of his friends, such as Burty and Piédagnel profess to admire these works, they savour too much of the awkward roughness of a modern peasant, transplanted suddenly into the world of Hellenic legend.

Millet returned to reality and to realism with the Peasants carrying a calf, in 1864 and the Pig-killers of 1869. But the greater part of his time from 1864 to 1870 was given up to a considerable series of drawings and pastels. He said that in these he wished to try the effects of his future oil paintings. In reality it was, as we shall presently try to show, his instinct which drew him to these media as the most perfect expression of his thought, his real artistic language. At this same period his travels, especially into Auvergne, in 1866, gave him new impressions and yet further increased the proportion of landscape in his work. He tried to express nature in a more complex way, to penetrate more deeply into it, "to grope into the bowels of it with constancy and labour" as he wrote after Bernard Palissy. Burty says that, in his last years he even came to "trying to put too many things into his painting. On a wall, a stone, the bark of a tree, he tried to make us see the successive deposits laid by time." But if his mind became more rich and complex, his heart grew more pure and tender with age; and his dark vision of country life was pierced towards the close of his days by a calmer feeling and by a domestic gentleness that finds its expression especially in his pictures of children.

***Having now marked out the main lines of his artistic development, let us try to define the technical methods and the style of Millet.

The first point to be noted is, that like most of the great French landscape painters of his time he did not paint nature from nature; he painted it in his studio. Some peasants and his maid served him as models. Most frequently however he contented himself with a few studies, rapid sketches, or even with the impression that he brought home from his lonely walks and long meditations. "He did not feel, he often said to me" (Wheelwright is the speaker) "the need of studying nature upon the spot, though he did sometimes take rudimentary notes in a pocket-sketch book no larger than one's hand. All the scenes that he desired to reproduce were fixed in his memory with marvellous exactness. He therefore attached great importance to exercise of the memory. He said that his own was naturally refractory, but that he had succeeded in training it, and that a memory-picture of this sort is more faithful, as to the general impression than one made from nature." From this cause comes the simplification of his landscapes and figures, the mind having retained only the leading features and eliminated those accessory details which do not immediately depend upon the impression as a whole. Thence, too, comes the rather planned, the almost abstract character of his realism. All that he says is true but it is rather a summary than a complete view.

The very studio in which Millet painted was of a special kind. Light hardly came into it. He said so himself: "You never saw me paint except in shadow; it is that half-light which I need to make my sight keen and my brain clear." It must be owned that this is a strange enough way of painting full daylight effects,—the high light of noonday in the open fields. Let us not forget that Millet's eyes often troubled him and that he was in danger of losing his sight. All this explains some characteristics of his painting and especially his rather murky light. This is especially noticeable in some of his most celebrated pictures, like the Gleaners, in which the illumination should be intense. About, who was a warm partisan of Millet did not fail to remark this fault but he excused it or wittily explained it in his Salon of 1857. "The August sun," he said, "sheds a powerful warmth upon the canvas, but you will not surprise any of these capricious rays which gambol like holiday schoolboys in pictures by Diaz; this is a grave sunshine which ripens wheat and makes men sweat and does not waste its time in frolics." But this "grave sunshine,"—too grave indeed—has not in reality the overwhelming splendour which is supposed by the three panting figures bowed above the burned ears of wheat; and Millet would not have failed to give it that splendour and so to impart the full value to his thought—if he had been able. It is surprising that neither this need of avoiding a strong light which he felt both in his eyesight and in his mind, nor yet his melancholy should have led him more frequently to represent the dark hours of the woods, and the poetry of shadow. But he mistrusted these too easy effects; he was afraid of sentimentality and might well have said, as Michael Angelo did to Francis of Holland: "good painting will never draw a tear." He particularly delighted in the first and last hours of the day, when the light falls level upon the upturned furrows as in The Angelus and when the distances are bathed in a fine powdery light, as in some of his Shepherds and Shepherdesses. And in spite of all this it cannot be said that he is a painter of half-tones. That term conveys an implication of softness and moderation that ill accord with the rather rough energy of his genius. To conclude, though he well knew how to express the soft glow of a warm light as he did in Gréville Church, in the Louvre, or the dramatic contrast between an opaque black sky full of storm and clear sunshine upon meadows and flowery orchards as he did in Spring in the same gallery, yet he was never, properly speaking, a great painter of light, still less a great colourist. He has been justly reproached with too often painting earth, flesh and stuffs all "with the same woolly and monotonous touch."[2] Yet he had a certain curiosity about the shades of stuffs. Wheelwright says that he had in his studio a collection of rags, handkerchiefs, skirts, and blouses, to suggest shades to him. "Blue was his favourite colour." He had innumerable shades of it, "from the crude indigo of the new blouse to the delicate tone of garments that had grown almost white by washing. He revelled in them." But his execution very often remains heavy and uniform; and our contemporary criticism which is but too much inclined to judge painting wholly and solely in respect of colouring has a good case against Millet. Huysmans does not know how to be angry enough with "his monotonous stingy oils, commonplace and rank, false and obliterated," "his rough and scurvy pictures, old and deaf," and "his uniform, russet figures under a hard sky;" and distinguishing the painter in pastels, whom he admires (and to whom we shall return) from the painter in oils, whom he abhors, he sees the latter as "a heavy worker on canvas imbued with the old scruples about a scheme of colour and the old ceremonies."But it is not enough to say that Millet was possessed by classic traditions and prejudices. In reality he was himself a classic painter, a great French classic of the race of Poussin; and if we would appreciate him justly we must judge him from that point of view and according to those principles. Far from seeing in him one of those revolutionary painters who create a new art, we must see him as a mind and painter of the seventeenth century transplanted into our world and applying an art of former days to the presentation of our contemporary world.[3] This is precisely his originality. His faults and his merits are those of a whole race of men of genius with whom, as we shall presently see, his relationship is very close.

***Millet himself has informed us clearly of his profound affinity with certain masters of the past. Nothing can be more interesting if we wish to know him than to read his written judgments of the paintings in the galleries of the Louvre.

We have seen already that, when he first stayed in Paris, the Louvre was the only thing which made him able to endure life in a city odious to him. There he found his only friends.

In the Louvre itself, however, his friendships were extremely exclusive. He scornfully repelled the advances of the enticing masters who belonged to the eighteenth century. He treats Boucher almost as severely as Diderot did. Like Diderot he would be ready to call aloud to him: "Leave the Salon! Leave the Salon!" He despises the "pornographic" painter[4] and his "melancholy women with their slender legs, their feet bruised in high heeled shoes, their waists diminished by stays, their useless hands and bloodless bosoms.[5] Boucher is nothing but an allurer." He is not disarmed even by Watteau who seems to him mournful. With a singular psychological penetration (which I have noted already in what he says of Decamps), Millet discovers the genuinely morbid and sad temperament of Watteau beneath the disguises of Fêtes galantes. He sees the "hidden melancholy of these theatrical puppets who are condemned to laugh." They remind him of marionettes, and he imagines that "all this little company was going to be put back into the box when the show was over, and weep there over its fate." He has a certain taste for some of Murillo's portraits, and for Ribera's St Bartholomew and Centaurs. It was curious that he did not at first fully understand Rembrandt; he was probably alienated by the thing that generally attracts: the magic of his light. I imagine that, at first sight Rembrandt must have appeared to him too much of a "virtuoso;" and he could never endure "virtuosity." "Rembrandt," he said, "did not repel me, but he blinded me." Only by degrees did Millet reach the profound truth and the sublime heart of Rembrandt. On the other hand though he was shocked by Rubens he forgave him everything because he was "strong." "I always liked what was powerful, and would have given all Boucher for a naked woman by Rubens." Millet passionately loved strength; and his usual designation of the masters was the strong men. His love of power and abundance led him sometimes to like artists most remote from himself: painters of the Italian decadence like the Rossos and Primatices at Fontainebleau, whose taste is poor and sometimes detestable, but who are full of the pulse of life: "They belong to the decadence, it is true. The accessories of their people are often ridiculous and their good taste doubtful; but what a power of creation, and how their rough good humour recalls past times! It is all as childish as a fairy-tale and as real as the simplicity of bygone ages. There are recollections in their art of the Lancelots and the Amadises. One could stay for hours before these kind giants." The most curious and characteristic of these judgments of Millet's is, in its very narrowness that which he delivers in a single line upon Velasquez. He never liked him. He understands, he says, the beauty of his painting: "but his compositions seem to me to have nothing in them."

His favourite masters were the Italian primitives, the French masters of the seventeenth century, and Michael Angelo.

It was a moral sympathy which drew him particularly to the primitives. He loved "these gentle masters who have made the creature so fervent, that it becomes beautiful—and so nobly beautiful, that it becomes good." Their piety, their simplicity and their suffering moved him. "I have retained," he said, "my first leaning towards the primitive masters, towards their subjects which are as simple as childhood, their unconscious expressions, their individualities which say nothing, but feel themselves overburdened by life, or suffer patiently without cries or complainings, undergoing the human law without even having an idea of asking satisfaction from any body. These men did not produce an art of revolt like ours today." Fra Angelico "gave him visions." But of all the Italians of the fifteenth century, the one who seems to have moved him most deeply is the harsh and tragic Mantegna. "Masters of his kind have an incomparable power. They throw in your face the joys and sorrows that possess them."[6]

Beside this great Italian school of the fifteenth century, he gave a place in his admiration, to the great French School of the seventeenth century: Le Brun and Jouvenet whom he considered "very strong"; Lesueur, "one of the great souls of our school"; and above all Poussin, "who is the prophet, the wise man and the philosopher of it, and also the most eloquent arranger of a scene. I could spend my life looking at Poussin's work, and never be satisfied."

But the master of masters who overwhelmed him and dominated him tyrannically, the genius whom he preferred to all others, was Michael Angelo. I have already quoted the passage in which Millet describes his first meeting with Michael Angelo's work, and the contagion of pain by which he was suddenly overcome at the sight of a drawing which represented a man in a swoon. "I saw very well," he added, "that the man who had done that was capable of personifying the good and evil of humanity in a single figure. It was Michael Angelo. To say that is to say everything. I had already seen some poor engravings at Cherbourg; but here I touched the heart, and heard the voice of him who haunted me so strongly all my life."

Such were his great friends. Among the moderns, Delacroix alone, whom he loved and defended violently against his enemies, and fifty of whose sketches he contrived in spite of poverty to purchase at the public exhibition of his works in 1864, was judged by Millet to take rank with Theodore Rousseau, and perhaps Barye among these, his chosen few. All the other contemporary artists, the painters of the Luxembourg gallery, seemed to him "repulsively insipid" and his antipathy to modern art applies not only to the productions, but to the very essence of this art. He explains himself clearly upon the point. "With us, art is no longer anything more than an accessory, a drawing room accomplishment, whereas formerly, and even down to the middle ages it was one of the columns of ancient society, its conscience and the expression of its religious feeling." The blame of this decadence lies not only with the artists; it rests on the whole of society and especially upon those who direct it or claim to direct it, the intellectual aristocracy: "What have the best brains of our period done for art? Less than nothing. Lamartine (I saw him choosing out his favourite pictures in the Salon of 1848) was only touched by a subject that corresponded with his political or literary interests. He would never have placed a picture of Rembrandt's in his own house. Victor Hugo puts Louis Boulanger and Delacroix on the same level. George Sand has a woman's prudence, and gets out of the question with fine musical words. Alexander Dumas is under the thumb of Delacroix, and apart from him does not think freely. I have not been able to dig out a single really felt page in Balzac, Eugène Sue, Frédéric Soulié, Barbier, Méry, etc.—a single page that might serve us as a guide, or that bears witness to a real understanding of art. Proudhon's work on art is a magnificent bit of special pleading, full of ingenious sallies, but it is a lecture fit for the blind asylum."[7] Millet, then, felt himself almost completely separated from all his period; and lived in communion of thought across the centuries, with a few great men: Mantegna, Michael Angelo, and Poussin. Let us endeavour to extricate from this selection and these judgments of Millet's the features which may serve to draw his own character.

*** We must note, to begin with, the unceremonious disdain with which Millet treats the colourists: Velasquez and Watteau. As to the painters of plastic beauty: Leonardo and Raphael he does not seem even to have given heed to them. His three preferred masters are the masters, pre-eminently, of style. A fine, clear, strong and expressive utterance: this was their ideal. The word "style" is never more fitly employed than in speaking of Mantegna, Michael Angelo and Poussin, and of this last in particular. Poussin himself in speaking of his works, said: "those who know how to read them properly." And Bernini, enraptured with Poussin's Extreme Unction, says that "it produced the same effect as a fine sermon, to which the hearer listens with very great attention and from which he goes away in silence but feeling the effect within."[8] Poussin and Mantegna unhesitatingly sacrifice beauty to style, and neither Poussin nor Mantegna, nor yet Michael Angelo is, truly speaking, a colourist; their colour is their weak point and Poussin, who recognizes this, does not hesitate to hold colour very cheap. "The singular application bestowed on the study of colour," said he, "is an obstacle which prevents people from attaining the real aim of painting; and the man who attaches himself to the main thing will acquire by practice a fine enough manner of painting."[9] And in another passage: "Colours in painting are as it were allurements to persuade the eye; and the same thing is true of the beauty of the verse in poetry."[10] No doubt it is praiseworthy to say things that are beautiful, but the essential is to say things that are clear and strong. To think rightly and speak one's thought clearly is the ideal of Poussin. It is also that of Millet.

One cannot be too careful to keep in mind Poussin's theories if one wishes to judge Millet. Millet had fed upon them. Very many points of his nature resembled Poussin's. Like him he was a Norman. He had a kindred mind, the same admixture of religion and philosophy, of high thinking with the good sense of a realist. He had also Poussin's rather dull and darkened eye, and his heavy hand. He had long been used to read Poussin's Letters and had assimilated his ideas. They may readily be recognized in his own expressed theories about art. Indeed, he does not conceal their origin but explicitly rests them upon Poussin.

"When Poussin," writes Millet in some notes upon art to Sensier who had asked for them, "when Poussin sent his picture of Manna to M. de Chantelou he did not say to him: See what a fine bit of colour, see how bold, see how it is put in, or any of the things of that kind to which so many painters seem to attach importance, I don't know why. He said: If you remember the letter which I wrote you touching the movement of the figures that I promised to put into it, and if you consider the picture altogether, I think you will easily recognize which are those that are languishing, those that are full of pity, and those that are performing charitable actions."

The matter would rather seem to be a book than a picture. "Characterisation, that is the aim," wrote Millet again. "In art one must have a main thought, express it eloquently, preserve it in oneself and communicate it to others strongly as though by the die of a medal." Note the words "thought" and "eloquently"; they conform closely to the intellectual ideal of the Seventeenth century. The aim of art is not form but expression. "To have done a certain number of things which say nothing is not to have produced something. He writes to Sensier on the 21st of October 1854, "There is only production where there is expression." Therefore Millet hated mere executive skill. "Woe to the artist who shows his talent rather than his picture! It would be laughable indeed if the wrist were to take the first place"; and he calls the hand "the very humble servant of the thought." He did not even allow that his way of painting might be admired, or that endeavours should be made to explain it. "As to explanations that may be given of my manners of painting, they would be lengthy, for I have not concerned myself with that matter; and if there are any manners, they can only have come from the way of entering more or less deeply into my subject, and from the difficulties of life, etc." Thus, the thought only should be a matter of attention. The point is not to seek a factitious originality, or a personal technique. The point is to think justly. Every line, every touch, as he showed Wheelwright, has a meaning. One must make oneself master of it. One must learn to see, that is to say, to draw[11]—to seize the "drawing of things," that is to say the vital and essential qualities of things. "The drawing of things," as Poussin says, "must be the exact expression of the ideas of things."

This point can only be reached if we are strongly moved by what we see. Impression forces expression. "I should like to do nothing which was not the result of an impression received from the appearance of nature, either in landscape or in figures.… Art began to weaken from the moment when people no longer rested directly and simply upon impressions coming from nature, and when executive cleverness at once came to take nature's place: then began the decadence."

The majority of critics make for themselves an abstract ideal of beauty, and judge all works according to this ideal, condemning them unless they find it observed and applied. Millet protests against these pedantic claims. In judging an artist one must inquire, not whether his figures or colouring conform to a certain general idea of beauty, but what is his personal idea, and whether he has expressed it well. "Our matter of concern with the artist is his aim and the manner in which he has attained it," wrote Millet to Camille Lemonnier in 1872. And elsewhere, in a letter written in June 1863 to the critic Pelloquet, on the subject of the Man with a hoe: "It is not so much the things represented which make beauty as the necessity which has been felt of representing them; and that very necessity creates the degree of power with which the task has been executed." He means (for Millet's style, like Poussin's, is often abstract and obscure, and a commentary is not unnecessary), he means, that the beauty or ugliness of the object represented matters little. The thing that counts in art is the passionate impulse that compels the artist to create his work, and it is this passion which gives the work its power of expression, and consequently its beauty; for it is the same thing. "Beauty does not dwell in the face; it glows in the entirety of a figure, and in whatever suits the action of the subject. Beauty is expression." Thus beauty is in the mind not in the body. Poussin wrote in the same way: "Beauty is altogether apart from the material body." And Lomazzo, the theorist of Michael Angelo's school, said: "La bellezza è lontana dalla materia."[12] Millet continues: "We may say that everything is beautiful if it comes in its right time and place, and on the contrary that nothing can be beautiful if it comes in the wrong place. Which is more beautiful, a straight tree or a twisted tree? That which best suits its position. I conclude this, then: The beautiful is the suitable" or in other words, is that which is in the right place and says well what it means to say.

It is evident that all this does not deal with plastic beauty. The only beauties that Millet seems to require from painting are clearness and force. "I would rather say nothing than express myself feebly." His are the conceptions of a writer, an orator, a man of action, a great intellectual artist whose aim is less to please by his work than to move men by his thought and his will.

Thence arise all those great qualities of Millet's work which may be called oratorical: their solid composition, their logic, their feeling of rhythm, their imperious unity which forces itself upon the mind like a fine speech. He taught Wheelwright the necessity of concentrating his attention upon his subject, seeing the principal point, and subordinating all the rest to it. A picture demands unity, equilibrium, poise and harmony, and this ought, according to Millet, to exist even between the picture and its frame. Like Poussin, he attached great importance to the frame, and often retouched the picture after it was framed. "A picture should be finished in its frame. It must be in harmony with its frame, as well as with itself." The unity of the work is the first principle. "Nothing is of account but the foundamental. I try to make things seem, not put together by chance and for this one occasion, but so that they have an indispensable and compulsory connection. A work should be all of a piece; I desire to put in fully every thing that is necessary, but I profess the greatest horror of the unnecessary, however brilliant." We seem to hear a French writer of the seventeenth century and of the school of Boileau, speaking. Everywhere must be a ruling idea, the "mother-idea," which governs the work, and according to the laws of which all the elements that contribute to the action are co-ordinated on a rigorous plan—all others being mercilessly shorn away as useless.

It is well to remark, however, that these principles are not those of Millet alone, but of Théodore Rousseau too, though he appears so unlike Millet and so much occupied with technical method and with arrangement of colours. The Barbizon painters are not, whatever may be supposed, essentially colourists; they have, above all, the classic French sense of composition, of the central idea and the unity of the whole. "Form is the first thing to be observed," said Rousseau to one of his pupils, M. L. Letronne. "Every touch is to be of value to the whole and to express something." "He always insisted upon this," continues Letronne, "and spoke but very little to me of colour. 'You thought perhaps,' said he, 'that in coming to a colourist you would be spared drawing?' Another day he said: 'What "finishes" a picture is not the quantity of details, it is the truth of the whole. No matter what the subject may be, there is always a principal object upon which your eye rests continually; the other objects are but complementary, they interest you less; beyond them, there is nothing for your eye: this is the true limit of the picture. This principal object must also chiefly strike those who look at your work. You must therefore come back to it again and again and assert its colour more and more.' He quoted the example of Rembrandt. 'If on the contrary your picture contains exquisite detail, equal from one end of the canvas to the other, the spectator will look at it with indifference. Everything interesting him alike, nothing will interest him. There will be no limit. Your picture may prolong itself indefinitely; you will never reach the end of it. You will never have finished. The whole is the only thing that is finished in a picture. Strictly speaking you might do without colour, but you can do nothing without harmony.'"

There are so many points of resemblance between some passages of this fine painting lesson and Millet's judgments that we may believe these principles to have been brought to maturity by the two friends in common, and that both must often have studied Poussin. When for instance Rousseau says: "The picture ought to be made in the first place in our brain. The painter does not make it spring into life on the canvas: he removes one after another the veils which concealed it," do we not seem to hear Poussin saying in his pride of intellect, after conceiving the idea of a picture: "The thought of it has been fixed, and that is the principal thing."

*** One of the natural consequences of Millet's intellectuality is that he was perhaps even greater still in his drawings than in his paintings. He felt himself more at ease in them. To pastels and drawings he gave his best work in the last stage of his life, after 1864. He began by a number of drawings in black chalk dealing with the whole range of peasant life; then little by little he introduced pastels, adding pale shades of colour; and finally used coloured chalks only, producing in this way about a hundred large subjects. In these he impresses us as a genuinely great master. Even those who, like Huysmans, are most opposed to Millet's art, recognise the equal power and originality both of his feeling and his technique in this medium. His faults disappear. The air is more buoyant, the light more liquid. Connoisseurs delight in the novelty of his method in pastel, in "his black chalk work, his thread-like outlines, his trails of pins, his borders with their cunning flavour of coloured chalks." Here we feel Millet to be in his own province of pure expression reduced to its essential elements. Here we feel that he is in direct contact with nature; the spontaneous impression which he receives from her is not stopped upon its way and chilled or falsified by manual difficulties or by that laborious application which is sometimes felt a little too much in some of his pictures. He says directly what he thinks, and his beholder seizes the meaning wholly, freely, and at first sight;— in the same way that some great musician, Schumann, for example, whose technical training, acquired late, often hampers his inspiration in his great orchestral works, delivers himself much more sincerely and with more simplicity and greatness in his Lieder and pieces for the piano. And while Millet's faults are mitigated here, his virtues show themselves at their full value. His modelling is magnificent and his touch large; these chalk drawings are works made to be seen at a distance, tone melts into tone, and their general effect is decorative.

In the case of an artist who subordinates the whole work to one leading idea, the value of the work is the value of the idea; details can never save it. It will be frankly good or bad; there is no middle course. This is the case with Millet, as About remarked: "What I adore in him," he wrote in 1866, "is that he sometimes goes wrong and makes absolutely earth-quaking false steps. When he happens to set his foot upon uncertain ground, he sinks in up to the neck. I like him better thus than if he had learned from a master the habit of always doing pretty well." His system of simplification sometimes approaches exaggeration, and gives to the movements of some of his figures an automatic character that comes within a hair's breadth of caricature.

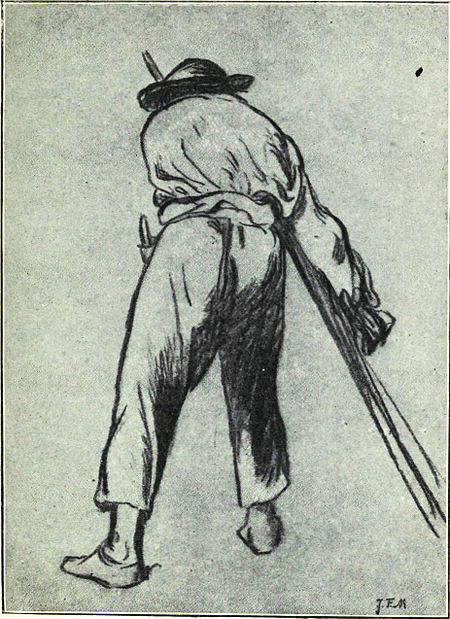

But, most frequently, he renders the characteristic essential features of his people as well as of the natural scenery to which they belong, with wonderful success. He imprints the moral physiognomy of beings and things in an indelible way. His vigorous mind, clear and free from complexities, imparts relief and noble expression to the outline, to the drawing that marks the limits of an object or a figure; he suppresses secondary details; he generalises the scheme. By these means he attains effects of epic power. A humble figure, a shed, an abandoned plough in a desert expanse, assume aspects of grandeur; the smallest gesture acquires a large solemnity. A Return to the Farm, by him, will involuntarily evoke the idea of a "Holy Family" or "Flight into Egypt." It would not be surprising to see the cradle of Moses floating on the majestic stream of that calm river over which his Women drawing water are bending. A simple sketch of a Woodcutter bowed double beneath his faggot, staggering under the burden, thin, wan, hollow-cheeked and lean of body, seems an emblem of man crushed by fate, unresisting, and knowing all struggles to be in vain.

The same spirit of generalisation causes Millet to be always seeking the type behind the individual. "If it were only a question of my will," he wrote to Lemonnier on the 15th of February 1873, "I should express the type very strongly, the type being, to my mind, the most powerful truth. You are perfectly right in attributing to me the intention of doing so." And this French classic, who devotes himself less to the observation of individuals than to the comprehension of social types, and less to passing gestures than to permanent acts, setting his whole strength to discriminate the transitor from the abiding, felt nothing and expressed nothing more firmly and more greatly than that primordial and Eternal existence from which everything comes and to which everything returns—the Earth. The earth is the real hero of his rustic poem; and living creatures are, to use André Michel's expression, only "lumps of it slowly brought to life." Huysmans justly remarks that it is as a painter of the Earth that Millet is especially distinguished. "Brute matter, the earth rises out of the framework, alive and exuberant. We feel it thick and heavy; through its clods and grasses, we feel it running deep and full. We breathe the scent of it, we could crumble it between our fingers. In most landscape painters the soil is superficial; in Millet it is deep." "Generally," said Burty, "the clods of earth and plots of grass come to the edge of the frame, their massing and drawing are exact, their values observed with knowledge, not predominating but giving a logical and solid groundwork to the various planes unfolded one beyond another until they merge into the sky amid the mists of the horizon." Let us recall the foregrounds of The Angelus and of The Sower, with their solidity, their living truth; and the immense plains stretching to the distance bathed in light and fading at the horizon into a fine haze. "The sky recedes beyond our sight, the fields are bathed in air." "Every landscape," said Millet to Wheelwright, "however small it may be, ought to suggest the possibility of indefinite extension; the tiniest corner of the horizon ought to be so painted as to make us feel that it is but a segment of the great circle which bounds our sight." And this, indeed, is the impression given by each of his pictures; none has the character of an isolated fact; it is part of a great whole. As the figures cannot be separated from the landscapes of Millet, as it would be impossible to take away the peasants seen in the open air "which makes them grey, brown and dull like the larks, the partridges and the hares of the field," so likewise none of his landscapes can be divided in our thoughts from the whole of nature, but calls up the vast expanses of the world that surround it. We feel that Millet, like Rousseau, "saw the universal before everything and in everything."

There was, moreover, as it were, a pre-established harmony between his genius and the scenery amid which he had chosen to dwell. The plain around the forest of Fontainebleau of which Millet had made the central point of his artistic existence, and of which the stretch is so vast, is not, as Wheelwright aptly remarks, in some respects unlike the Roman Campagna. Its details melt into an impression of grand and simple unity. The constant contemplation of these wide horizons with their classical element was well adapted to inspire Millet and to strengthen his natural inclination towards the simplified, the unified, and the abstract. The plain of Fontainebleau was to Millet very much what the Campagna of Rome was to Poussin.[13]

*** Friends and enemies alike acknowledged the classic character of Millet's style and spirit. Some criticised while others admired their application to the subjects which he treated; but none found it possible to deny their existence. The names of Homer, Michael Angelo and Raphael, recollections of the Bible and comparisons with antique art appear again and again when Millet's work is spoken of in articles upon the Salons from 1853 to 1875. Gautier said of the Harvesters' meal of 1853; "Some of these thick-set peasants display a Florentine air and lie in attitudes that might be those of Michael Angelo's statues. They have the majesty of toilers in touch with nature." Paul de St Victor, in turn, writes: "The picture of the Harvesters is a Homeric idyll translated into a rustic dialect. The countrymen seated in the shadow of the heaped up corn have a splendid animal, primitive ugliness, like that of the Æginetic statues and of the figures of captives sculptured on Egyptian tombs." Gautier says of the Peasant grafting a tree, in 1855: "The man has the appearance of accomplishing some rite of a mystic ceremonial, or of being the obscure priest of some rustic deity." About the Gleaners he says, "I might almost say that it presents itself as a religious painting," and Gerôme: "He is a Jupiter in wooden shoes." Theophile Silvestre remarks: "His pictures are expressed like psalms. This is the antique in painting." Even Baudelaire, when he desires to criticise Millet whom he does not like, does so not by denying but by emphasising the classical nature of his talent. "M. Millet," he says, particularly aims at style; he does not conceal the fact, he displays it and glories in it. But style does not succeed with him. Instead of simply drawing out the poetry inherent in his subject, he wishes, at all costs, to add something to it. All his peasants are outcasts on a small scale and have pretensions to philosophy, and melancholy, and the Raphaelesque." Baudelaire had too little simplicity of mind to understand that any man of his own day could still be naturally and simply classical as Millet was; but his ill-will did not prevent him from noting pretty fairly the essential characteristics of this art which was so much opposed to his own. He is quite right in saying that "Millet always adds something" to his subject. It is indeed the principal interest of his works that he always adds the soul of Millet to them. That is what gives them their greatness and makes them touching in so unique a way. At the first blush, there may seem something strange in a comparison between the noble poems of Raphael or Poussin and these representations of rough peasant life. But piercing through these scenes of humble realism, we feel a spirit that is inwardly sublime and that radiates sublimity. "One must know how," he said, "to make the trivial serve to express the sublime; in that lies real strength."[14] No man ever did this more constantly and more naturally than he. To him visible shapes were but a means of reaching the soul of things: "Ah, I wish I could make those who look at what I do, see the terrors and the splendours of night. I wish I could make them hear the songs, the silences, the rustlings of the air. I wish I could make infinity perceptible."

He mingled the poetry and emotion of his heart with everything that he saw. He is unique rather through the heart than through his art as a painter. That lofty, melancholy heart of his had none like it, save the heart of Michael Angelo. He is a kind of democratic Michael Angelo. "O Dante of the yokels, Michael Angelo of clowns" Robert Contaz called him, in a sonnet, in 1863. Some of his friends perceived, indeed, a certain physical likeness between Michael Angelo and him (rather, I imagine, in the general expression than in actual feature). See the portrait of Millet in a woollen cap, of the year 1847.

Assuredly Millet's disposition was remote from the heroic poetry and frenzied passion of the great Florentine. But he had an austere and pure realism of his own. He had also his amazing and eternal gravity. No ray of gaiety ever lightens his work. Everything is grave, the figures whom he choses and the actions which he assigns to them. There is no love; there are few or no anecdotes; he rarely paints young men; and the women whom he represents are all at work; they are sewing, turning hay, shearing sheep, carrying pails or fulfilling motherly duties, feeding and teaching children. The highest poetry and the only joy of his work lies in family affection. There is no room here for useless beauty. Millet said of Jules Breton's country girl: "They are too pretty to stay in the village." On every man and every woman he imposes the necessity of work. "My programme is work."

And, undoubtedly, it would be an exaggeration to say that this work is always sad. There are moments of calm, and of gentle content, the effect of which is perhaps the more agreeable for not being habitual. Then comes the deep comfort of hours of rest and silence.[15] Then we see the quiet and silent tenderness of home, motherly cares, The Meal, given to these nestlings, The Reading Lesson to the very attentive little maiden, the great events of childhood, The first steps. But the groundwork is always serious; and as soon as work resumes its place, there comes a character of tragedy. We feel the pressure of a divine law, a religious fate, weighing upon all creatures. Everywhere man is seen in conflict with the earth. It is a vast battle of which the year beholds the epic incidents: seed-time, harvest, red sunsets, pallid dawns, storms, the fall of the leaf, the passage of migrating birds, the succession of days and months; for nothing is insignificant, everything seems to play its part in this warfare between man and nature. Even in landscapes from which the human figure is absent, and in which day is breaking over sleeping lands, the conflict is heard muttering, ready to break out afresh. Thus we feel it in a chalk drawing that represents A plain at daybreak, empty, with a harrow lying in the fields and a plough standing upright beneath a cloud of rooks. Here we behold as Huysmans says again: "a truce between the earth and man; but the truce is on the point of being broken; and we feel that directly the sun is up "the dumb battle will begin again between the persistent peasant and the hard earth." Another chalk drawing again represents a vast plain in the first glow of dawn; and here, in the distance, the enemy is already seen advancing: a shepherd with his flock. "His tall figure black against the light has an indescribable air of hostility." And as the hours of the day go on, this silent struggle continues, ever harsher, ever fiercer beneath the consuming sun, until man is worn out; conquered by his own victory like the Man with a hoe, standing, bent, his body broken, his mind annihilated, in the glory of the light, or the Vine-dresser resting, with his burning eyes, his open mouth, his arms dropping between his outstretched legs, sitting, damp with sweat, stifled with heat;—until at last the inevitable end comes, and Death sets a limit to the long task and the many hardships:

"A la sueur de ton visaige

Tu gagneras ta pauvre vie;

Après long travail et usaige

Voicy la mort qui te convie."[16]

Millet's work has been justly considered as a poem of country life wherein all the occupations of the year are described. It has been likened to the poems of Hesiod, where the mystic abstraction of the thinker is found side by side with the familiar precepts of the Almanach du bon laboureur. In particular his work recalls, to some minds, those mediaeval calenders in which cathedral sculptors and Franco-Flemish illuminators, presented with untiring interest the larger scenes of country life.

But Millet's calender is one that has no festivals, a gospel of labour and domesticity. On its title, as has been truly said,[17] must be written the words of the Imitation: "Renounce frivolous matters." "Relinque curiosa."

- ↑ My Dear Rousseau,—I do not know whether the two sketches I send you will be of any good to you. I am only trying to show where I should put my figures in your composition.

- ↑ Sensier gives from one of Millet's letters a list of the colours that he used, which were all the most common earths "3 burnt sienna; 2 raw sienna; 3 Naples yellow; 1 burnt Roman ochre; 2 yellow ochre; 2 burnt umber.

- ↑ It should be added that this transposition is rendered easier by his choice of subjects. The world painted by Millet is the world of the common people and of the country, which is least subject to the laws of change and retains, even at the present day, many features in common with the life of two centuries ago.

- ↑ "What do you expect Boucher to put on the canvas? What he has in his imagination; and what can there be in the imagination of a man who spends his life with women of the lowest stamp." (Diderot.)

- ↑ "Our clothing depraves form. Our legs are cut by garters; the bodies of our women are stifled by bodices, our feet are disfigured by narrow hard shoes." (Diderot.)

- ↑ He had also a great predilection for Spanish primitives, like Greco, who in his day was very little known. He had a picture by him hanging in his room near his bed and used to look at it with emotion in his last illness. He said: "I know few pictures which touch me, I will not say more, but so much; a man must have had a great deal of feeling to paint a thing like that."

- ↑ This is P. J. Proudhon's work "On the Principles and Social Destination of Art." At first sight it would seem as though Millet might have sympathised with the programme put forth by Proudhon; (To paint men in the sincerity of their nature and their habits, at their work, accomplishing their civic and domestic duties, with their actual countenances, above all without posturing; to surprise them in the undress of their consciousness, as an aim of general education: such seems to me the real starting point of modern art." But Proudhon wished to make art subserve political ends, and Millet would not have that. Moreover Proudhon does not so much as name Millet, and his whole book seems written to extol Courbet alone.

- ↑ "Journal of the Travels in France of the Cavalière Bernini," by M. de Chantelou ("Gazette des Beaux Arts," 1877-85).

- ↑ Quoted by Reynolds in his fifth Lecture.

- ↑ Quoted by Bellori.

- ↑ "To see is to draw," said Millet to Wheelwright.

- ↑ "Beauty is remote from matter."

- ↑ To note one more point of resemblance between these two masters, it may be remarked that most of the paintings of both are conceived like large pictures and carried out on a small scale, so that they often produce the effect of being reductions from large decorative compositions. This is another result of the power of simplication and generalisation which characterises their genius.

- ↑ He was far, however, from desiring to confine art to his own personal province of rustic art. On the contrary, in opposition to Proudhon, he fiercely defended the right of art to represent other subjects than those of contemporary life. "Where, then, is personal impression? Cannot one be moved by a book that speaks of the past? Where would the picture of the Crusaders at Constantinople be if Delacroix had been compelled to paint the taking of the Trocadero or the opening of the Legislative Chambers?"

- ↑ Millet had met with an expression in Milton which had struck him greatly as according with his own feeling: "Silence listens." (It is curious to add that this expression is not Milton's but that of his French translator, Delille; Milton wrote: "Silence was pleased."

- ↑

"Thy life thou shalt gain

In the sweat of thy brow;

After long toil and pain

Death beckons thee now."This old verse is to be found beneath an engraving by Holbein described by George Sand in her Mare au Diable, the reading of which greatly impressed Millet and partly inspired his Death and the Woodcutter.

- ↑ By Ernest Chesneau.