LECTURE XXXII.

"Yes, that's like your feeling, just. I want my salts, and you tell me there's nothing like being still for a headache. Indeed? But I'm not going to be still; so don't you think it. That's just how a woman's put upon. But I know your aggravation—I know your art. You think to keep me quiet about that minx Kitty,—your favourite, sir! Upon my life, I'm not to discharge my own servant without—but she shall go. If I had to do all the work myself, she shouldn't stop under my roof. I can see how she looks down upon me. I can see a great deal, Mr. Caudle, that I never choose to open my lips about— but I can't shut my eyes. Perhaps it would have been better for my peace and mind if I always could. Don't say that. I'm not a foolish woman, and I know very well what I'm saying. I suppose you think I forget that Rebecca? I know it's ten years ago that she lived with us—but what's that to do with it? Things aren't the less true for being old, I suppose. No; and your conduct, Mr. Caudle, at that time—if it was a hundred years ago—I should never forget. What?

"I shall always be the same silly woman?

"I hope I shall—I trust I shall always have my eyes about me in my own house. Now, don't think of going to sleep, Caudle; because, as you've brought this up about that Rebecca, you shall hear me out. Well, I do wonder that you can name her! Eh?

"You didn't name her?

"That's nothing at all to do with it; for I know just as well what you think, as if you did. I suppose you'll say that you didn't drink a glass of wine to her?

"Never?

"So you said at the time, but I've thought of it for ten long years, and the more I've thought the surer I am of it. And at that very time—if you please to recollect—at that very time little Jack was a baby. I shouldn't have so much cared but for that; but he was hardly running alone, when you nodded and drank a glass of wine to that creature. No; I'm not mad, and I'm not dreaming. I saw how you did it,—and the hypocrisy made it worse and worse. I saw you when the creature was just behind my chair; you took up a glass of wine, and saying to me, 'Margaret,' and then lifting up your eyes at the bold minx, and saying 'my dear,' as if you wanted me to believe that you spoke only to me, when I could see you laugh at her behind me. And at that time little Jack wasn't on his feet. What do you say?

"YOU NODDED AND DRANK A GLASS OF WINE TO THAT CREATURE."

"Heaven forgive me?

"Ha! Mr. Caudle, it's you that ought to ask for that: I'm safe enough, I am: it's you who should ask to be forgiven.

"No, I wouldn't slander a saint—and I didn't take away the girl's character for nothing. I know she brought an action for what I said; and I know you had to pay damages for what you call my tongue—I well remember all that. And serve you right; if you hadn't laughed at her, it wouldn't have happened. But if you will make free with such people, of course you're sure to suffer for it. 'Twould have served you right if the lawyer's bill had been double. Damages, indeed! Not that anybody's tongue could have damaged her!

"And now, Mr. Caudle, you're the same man you were ten years ago. What?

"You hope so?

"The more shame for you. At your time of life, with all your children growing up about you, to——

"What am I talking of?

"I know very well; and so would you, if you had any conscience, which you haven't. When I say I shall discharge Kitty, you say she's a very good servant, and I sha'n't get a better. But I know why you think her good; you think her pretty, and that's enough for you; as if girls who work for their bread have any business to be pretty,— which she isn't. Pretty servants, indeed! going mincing about with their fal-lal faces, as if even the flies would spoil 'em. But I know what a bad man you are—now, it's no use your denying it; for didn't I overhear you talking to Mr. Prettyman, and didn't you say that you couldn't bear to have ugly servants about you? I ask you,—didn't you say that?

"Perhaps you did?

"You don't blush to confess it? If your principles, Mr. Caudle, aren't enough to make a woman's blood run cold!

"Oh, yes! you've talked that stuff again and again; and once I might have believed it; but I know a little more of you now. You like to see pretty servants, just as you like to see pretty statues, and pretty pictures, and pretty flowers, and anything in nature that's pretty, just, as you say, for the eye to feed upon. Yes; I know your eyes,—very well. I know what they were ten years ago; for shall I ever forget that glass of wine when little Jack was in arms? I don't care if it was a thousand years ago, it's as fresh as yesterday, and I never will cease to talk of it. When you know me, how can you ask it?

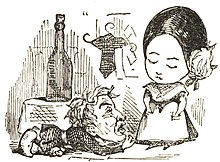

MRS. CAUDLE DISCHARGES "KITTY." |

"And now you insist upon keeping Kitty, when there's no having a bit of crockery for her? That girl would break the Bank of England—I know she would—if she was to put her hand upon it. But what's a whole set of blue china to her beautiful blue eyes? I know that's what you mean, though you don't say it.

"Oh, you needn't lie groaning there, for you don't think I shall ever forget Rebecca. Yes,—it's very well for you to swear at Rebecca now,—but you didn't swear at her then, Mr. Caudle, I know. 'Margaret, my dear!' Well, how you can have the face to look at me———

"You don't look at me?

"The more shame for you.

"I can only say, that either Kitty leaves the house, or I do. Which is it to be, Mr. Caudle? Eh?

"You don't care? Both?

"But you're not going to get rid of me in that manner, I can tell you. But for that trollop—now, you may swear and rave as you like—

"You don't intend to say a word more?

"Very well; it's no matter what you say—her quarter's up on Tuesday, and go she shall. A soup-plate and a basin went yesterday.

"A soup-plate and a basin, and when I've the headache as I have, Mr. Caudle, tearing me to pieces! But I shall never be well in this world—never. A soup-plate and a basin!"

"She slept," writes Caudle, "and poor Kitty left on Tuesday."