ORDER VII. GRALLÆ.

(Wading-birds.)

The birds of this Order are characterized by the great length of the tarsus and leg, and by having the lower portion of the latter destitute of feathers, and covered with regular plates like the former. They are thus enabled to wade into the water to a considerable depth without wetting their plumage; and thus to seize fishes, and other animals of the waters, on which they feed. To facilitate this object, the beak is usually greatly lengthened, as is also the neck. Deriving thus their support from the water, while yet they are destitute, at least generally, of the power of swimming, they form an interesting link of connection between the terrestrial and aquatic birds. The typical Families alone, however, maintain this intermediate character; for while on the one hand, the Plovers and the Cranes, both in the nature of their food and in their terrestrial habits, conform rather to some of the Gallinaceous or Cursorial groups,—on the other, the faculty of swimming possessed in great perfection by the Rails, with their correspondent habits, bring them into close association with the Natatorial type.

The wings of the Waders are usually long and powerful; and hence the flight of these birds is rapid and well sustained: many of them make periodical migrations, and are thus widely distributed over the globe. They commonly stretch out their long legs behind the body during flight, thus maintaining their balance, which otherwise, from the extreme shortness of their tails, might be difficult. Those genera which are most aquatic place their nests among the reeds and herbage of marshy places, or, as the Herons, build in society on trees; those which frequent dry and stony places, frequently lay their eggs on the bare ground, or content themselves with such protection as a tuft of grass may afford. The eggs are usually marked with spots on a coloured ground; they are commonly of a lengthened form, with one end much pointed.

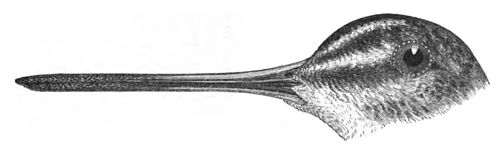

HEAD OF SNIPE

Family I. Charadriadæ.

(Plovers.)

In this extensive group the feet are long and slender, adapted for swift running; the toes comparatively short, and the hind one either wanting, or in the few cases where present, so small as to be little more than rudimentary; the wings are long and pointed, and the flight rapid and powerful. Plovers live chiefly on sandy and unsheltered shores, or on dry, exposed commons; they associate in flocks, run with great swiftness, and fly in great circles, somewhat like pigeons,

HEAD OF PLOVER.

wheeling round at no great height, with loud piping cries. Their head is thick, with large dark eyes, placed far back; the beak is short, the basal half soft and compressed, the outer half abruptly swollen, and often slightly notched, so as to present some resemblance to that of a Pigeon. The nostrils are pierced in a long groove.

The colours of the Plovers are not showy, but are chaste and beautiful: various shades of brown, mingled with ochraceous tints, and diversified with white and black, frequently disposed in bands, may be considered as most prevalent among them. The plumage is generally subject to periodical changes; a gayer and more varied dress being assumed for the nuptial season, than that displayed in winter. Many of them are active during the night; they feed on worms, slugs, &c. The species are scattered over the whole globe.

Genus Vanellus. (Briss.)

The Lapwings are distinguished by having the beak straight, slightly compressed; the tips of both mandibles smooth and hard; the groove of the nostrils wide, deep, and reaching to the swollen part of the beak; the nostril pierced in the middle of it; the wings ample, more or less rounded; fourth and fifth quills longest; the shoulder armed with a spur; the feet slender, the tarsal plates taking a net-work form; the toes united at the base by a small membrane; a minute hind toe, jointed on the tarsus. They inhabit the Old World; breed inland; associate in flocks, which are very clamorous when their haunts are approached in the breeding season. At the approach of winter they migrate to the seaside, when they appear in a different condition of plumage.

The common Lapwing or Peewit (Vanellus cristatus, Meyer) is one of the most beautiful of the Plovers. In its nuptial plumage, the crown, face, neck, and breast are of a deep and rich black, with a green gloss; from the hind head springs a most elegant crest of long black feathers, curving upwards, capable of being erected; the upper parts of the body are pale olive brown, with metallic reflections of purple and blue; the sides of the head, the base of the tail, and whole under parts are pure white, except the under

LAPWING

The Lapwing is spread over the northern half of the Eastern Hemisphere, from Ireland to Japan, and from Iceland to Calcutta. In this country it is partially migratory; for though many reside with us all the year yet "numbers leave these islands, and others annually perform a periodical migration to the breeding-grounds, arriving there with as much regularity as our summer visitors from a distance."[1] Large downs, the sheep-walks of an open unenclosed country, wild heaths, and commons, boggy pastures, wet meadow-lands, and marshes near lakes and rivers, are the favourite resorts of these beautiful birds. In such situations immense numbers congregate at the breeding-season, separating into pairs to assume the parental joys and cares. "When incubation has fairly commenced," observes Sir William Jardine, "the common or moor often appears alive with their active motions; no stranger or intruder can enter upon their haunts without an examination, and both, or one of the pair, hover and fly around, tumbling and darting at him, and all along uttering their vehement cry of Peeswit. When incubation is completed, the young and old assemble together, and frequent the pastures and fallows; some particular fields being often chosen by them in preference to others, probably on account of the abundance of food; and here they will assemble daily for some time, feeding chiefly in twilight or clear nights, and resting during the day.

The clouds of birds that rise about sunset, to seek their feeding-grounds, performing many beautiful evolutions ere they go off, is incredible, except to one who has witnessed it. In Holland, where this bird is extremely abundant, and where the view on all sides is bounded equally by a low horizon, thousands may be seen on all sides at once, gleaming in the setting sun, or appearing like a dense black moving mass between its light and the spectator."[2]

The eggs of this bird are nearly two inches long, of an olive hue, spotted all over with blotches of brown. Four are laid, in some slight depression of the ground, on which a few blades of dried grass form the only nest. These eggs are well known as an esteemed luxury for the table, and may be seen in the shops of the London poulterers in great numbers in the months of April and May. The flat and low counties around the metropolis afford the chief supply to this market; and the trade of collecting them affords employment to many individuals during the season. "Great expertness in the discovery of the nests is shewn by those accustomed to it, who generally judge of their situation by the conduct of the female birds, which invariably, upon being disturbed, run from the eggs, and then fly near to the ground for a short distance, without uttering any alarm-cry. The males, on the contrary, are very clamorous, and fly round the intruder, endeavouring, by various instinctive arts to divert his attention. So expert have some men become, that they will not only walk straight towards a nest, which may be at a considerable distance, but tell the probable number of eggs it may contain, previous to inspection; generally judging of the situation and number of eggs by the conduct of the female bird. In some counties, however, all the most likely ground is carefully searched for eggs once every day, by women and children, without any reference to the actions of the birds.[3] Dogs are also trained to search for the eggs. The food of the Lapwing consists largely of earth-worms, to which are added slugs, insects and their larvae, and small crustacea. It is not unfrequently kept in gardens, where it soon becomes an interesting pet, and by its destruction of vermin proves useful. Its mode of obtaining earthworms is thus described by Dr. Latham: "I have seen this bird approach a worm-cast, turn it aside, and after walking two or three times about it, by way of giving motion to the ground, the worm come out, and the watchful bird, seizing hold of it, draw it forth,"

Family II. Ardeadæ.

(Herons.)

Mr. Swainson considers that the Herons shew the strongest affinity to the Ostriches, but we confess that to us they appear to present more points of dissimilarity than resemblance. They are decidedly carnivorous in their appetite, feeding on fishes, aquatic reptiles, small mammalia, mollusca, worms, and insects. The Cranes, however, are more terrestrial than the others, and join with an animal diet, grains, seeds, and herbage. The legs and feet in these birds are long and slender, as is also the neck, which is very flexible: the beak is long, straight, sharp-pointed, firm in texture, and very powerful; in some genera it is of great thickness and strength. The Spoon-bills, however, shew an exception to the sharpness of this organ; and the Curlews to its straightness. The wings are, in general, well developed, and some of the genera are birds of soaring and powerful flight. The hind toe is always present, but its position and development vary in different genera.

The typical Herons have the above characters in greatest perfection: they are the most beautiful of all the Waders, not so much from the colours of their plumage, which however are chaste and agreeable, as from their taper and graceful forms, the curves of their slender necks, and the elegant hanging crests, and long decomposed plumes that adorn various parts of their bodies. Their plumage is copious, but somewhat lax, particularly on the neck. They build in society, but live solitary. Their common habit is to watch patiently, and without motion, on the margin of the water, or within the shallows; on the appearance of prey, it is transfixed by a sudden stroke of the pointed beak with lightning-like rapidity, and swallowed whole.

The Ardeadæ are to be found, in some of their varied forms, in all parts of the globe; the typical genera are numerous in species, and widely distributed. Some of their characters are thus graphically summed up by Willoughby: "These have very long necks; their bills also are long, strong, ending in a sharp point, to strike fish, and fetch them from under stones or brinks; long legs, to wade in rivers, and pools of water; very long toes, especially the hind toe, to stand more firmly in rivers; large crooked talons, and the middle serrate on the inside, to hold eels and other slippery fishes the faster,[4] or because they sit on trees; lean and carrion bodies, because of their great fear and watchfulness." Genus Botaurus. (Briss.)

The Bitterns are distinguished by having the beak as long as, or rather longer than, the head, strong, higher than broad, the mandibles of equal length, the upper mandible slightly curved downwards. The nostrils are basal, linear, longitudinal, lodged in a furrow, and partly covered by a naked membrane. The legs are comparatively short and strong, the toes long and slender, all unequal, the middle toe as long as the tarsus; the hind toe on the level of the others; the claw of the middle toe serrated on its inner edge. The wings are long, rather rounded, the first three quills longest, and nearly equal. The back of the neck is bare of feathers, but the plumage of the sides, which is particularly long and lax, ordinarily meets across the back.

The Bitterns are spread over both hemispheres, but are not found in Australia; they are nocturnal birds, which love to skulk in the cover of reeds, and other aquatic herbage, through which their remarkably thin, compressed bodies enable them to run with great ease and celerity. Their voices are loud and hollow, sometimes harsh and piercing. The general colours of the plumage are yellow, merging into rufous, and black; the latter frequently taking the form of numerous spots or freckles; at other times the hues are disposed in broad masses, and the black is replaced by a deep sea-green, with metallic reflections.

The name of the Common Bittern (Botaurus stellaris, Linn.), or, as it was formerly spelled, Bittour, was probably derived from its voice, which, uttered as the bird rises spirally to a vast height in the dusk of evening, is thought to resemble the deep-toned bellowing of a bull. The names which are given to the species, in some of the rural districts of England, such as Bull of the bog, Mire-drum, &c., refer to this booming sound.

The Bittern is a bird of much beauty; the ground-colour of its plumage is bright buff, marked with innumerable streaks, freckles, and crescents of black; the crown is black, with green and purple glosses. The plumage of the neck can be thrown forward, and made to assume the appearance of a thick ruff. The legs and feet are grass-green.

In former years the Bittern was common throughout Great Britain, but owing to the increase of cultivation, the reclaiming of waste-lands, and the drainage of marshes, it has gradually become less frequently met with, and may now be classed among the rare British birds. Yet, from circumstances unexplained, it is even now, in some years, comparatively numerous in favourable localities, where, perhaps, for several seasons before and after, not a specimen is to be seen. Its occurrence is therefore considered as an event of sufficient interest to be recorded. The winters of 1830-31, 1831-32, and 1837-38, were remarkable for the number of specimens that were procured. Instances of the breeding of this species are rare in England.

On the continent of Europe, however, the Bittern appears much more common; nor is it confined to this quarter of the world; for specimens, procured in Sweden, Barbary, South Africa, Siberia, Bengal, and Japan, do not appreciably differ from each other.

The Bittern is a voracious feeder: small mammalia, birds, and fishes, alternate with frogs, newts, slugs, and insects, to satisfy his appetite; and the former are not always of the smallest.

COMMON BITTRRN.

Sir William Jardine has found a Water Rail whole in the stomach of one; and from that of another, Mr. Yarrell has taken the bones of a pike of considerable size; and in a third instance a Water Rail whole, and six small fishes. In Graves's "British Birds," it is stated that in one dissected in 1811, the intestines were distended with the remains of four eels, several newts, a short-tailed field-mouse, three frogs, two buds of the water-lily, and some other vegetable substances. It is chiefly during the night that the Bittern feeds; by day he remains skulking among the reeds or coarse weeds of the marsh, or river-margin, and is not easily flushed. On the approach of night he emerges from his retreat, and rising on the wing soars in spiral circles to a great height, uttering, as he goes, his hollow boom. Goldsmith's description of this sound, to which superstition was wont to attach somewhat of an unearthly character, is poetical and interesting, the rather because he seems to speak from observation. "Those who have walked in an evening by the sedgy sides of unfrequented rivers must remember a variety of notes from different water-fowl; the loud scream of the wild-goose, the croaking of the mallard, the whining of the lapwing, and the tremulous neighing of the jack-snipe. But of all those sounds there is none so dismally hollow as the booming of the Bittern. It is impossible for words to give those, who have not heard this evening call, an adequate idea of its solemnity. It is like the interrupted bellowing of a bull, but hollower and louder, and is heard at a mile's distance, as if issuing from some formidable being that resided at the bottom of the waters." And he adds, "I remember in the place where I was a boy, with what terror this bird's note affected the whole village; they considered it as the presage of some sad event, and generally found or made one to succeed it. I do not speak ludicrously; but if any person in the neighbourhood died, they supposed it could not be otherwise, for the night-raven had foretold it; but if nobody happened to die, the death of a cow or a sheep gave completion to the prophecy."[5]

A wounded Bittern fights with desperation, lying on its back and endeavouring to clutch its adversary with its claws, as well as striking vigorously with its sharp, formidable beak. Hence, in the days of falconry, when this bird, which was favourite game, was brought down, it was the duty of the falconer to run in quickly, and seizing the beak of the Bittern, to plunge it into the firm ground, to prevent injury to the Falcon; an operation not without danger, as the Bittern generally aims to strike the eyes.

The comb-like divisions of the inner edge of the middle claw, which we find in all the Herons, have given rise to no little difference of opinion on the subject of their intended purpose. The structure is found in widely different birds, such as the Nightjar among the Fissirostral Passeres, and the Frigate-bird among the Pelecanidæ. From our own observation, we have no doubt of its object being the freeing of the plumage from insect—parasites. A glance at its structure will shew that no greater power of grasping or of holding a branch is, or can be possessed by a claw having these narrow parallel slits in its edge (for they are not serratures) than by one of the ordinary structure.

Family III. Scolopacidæ.

(Snipes.)

The most remarkable characteristic of this Family is the extreme length and slenderness of the beak, which, far from possessing the strength and firmness of the Herons, is extremely weak and flexible. Of course this structure is more conspicuous in what are known as the typical genera, than in those which lead off from them into connexion with neighbouring Families. In the former the tip of this long beak is covered with a soft skin, extremely sensitive; and the organ is employed as a probe to feel the soft mud or earth, into which it is thrust, and to capture there minute insects and animalcules, which could not be discovered by any other sense. They have the hind toe jointed on the tarsus above the level of the fore toes, and so short as to be unable to touch the ground. In some it is absent.

The feet and necks of these birds are, generally, of moderate length; the wings long and pointed; and hence the flight is swift and sustained: the tail is short and even; the front toes frequently united by a membrane more or less considerable. Their plumage is of chaste and subdued tints, frequently presenting a mottled assemblage of black, white, and rufous hues, often disposed in elegant contrast; at other times a nearly uniform greyish olive is the prevalent hue. Their flesh is held in high esteem.

The Snipes are widely distributed; a considerable number of the species are found in Britain, where, however, they are all more or less migratory in their habits. The majority of them frequent marshes, the banks of lakes and rivers, or the seacoast, on which they run with great swiftness. A few species affect the shade of woods and coppices, but even these select, as favourite resorts, the most humid spots they can find. They lay four eggs, of a somewhat conical form, with but little nest; and the business of incubation is performed on the ground of inland moors and fens. The young are able to run about as soon as they escape from the shell; when they are clothed with down. With the exception of a very few polygamous species, the females are larger than the males. Many of them feed, and perform their migrations during the night, and these have the eye very large in proportion to the head.

Genus Scolopax. (Linn.)

The following are the generic characters of the restricted Snipes, inclusive of the Woodcocks. The beak is lengthened, straight, flattened at the base, slightly curved at the tip, where it is dilated; the tip of the lower mandible fitting into the upper; the legs and feet are slender, moderately long; the wings moderate, the first or second quills the longest.

Of the five species of this genus which are met with in England, either permanently or occasionally, we select the Common Snipe (Scolopax gallinago, Linn.) to illustrate the Family. Its ground colour is a rich dark brown, so deep in some parts as to be almost black, variously spotted, striped and banded with white, which, on the back, is suffused with rufous; the under parts are white, beautifully and regularly banded on the sides with black. The end of the beak, as Mr. Yarrell has observed, "when the bird is alive, or recently killed, is smooth, soft, and pulpy, indicating great sensibility; but some time afterwards

COMMON SNIPE.

The mode of feeding, in which this well-endowed organ comes into requisition, is not a little singular. A writer in the "Magazine of Natural History" thus describes it, as observed by himself with a powerful telescope: "I distinctly saw them pushing their bills into the thin mud, by repeated thrusts, quite up to the base, drawing them back with great quickness, and every now and then shifting their ground a little." And we have ourselves seen a closely-allied species feeding at less than half a stone's cast distance, wading in water that reached just above the tarsal joint. At this depth the beak could just touch the bottom, and thus it walked deliberately about, momentarily feeling the mud with its sensitive beak-tip, striking with short perpendicular strokes, without withdrawing the beak from the water. The action of swallowing, now and then, was distinctly perceived. We observed that when thus occupied, the faculties were so absorbed that the bird appeared unconscious of danger, nor could it be roused, though so near, without repeated shouts.

The Snipe breeds with us, selecting the edges or drier spots of the wet moors and fens, or the barren heaths of the northern districts. About the beginning of April, the male Snipe begins to utter his calls of invitation to his mate. "At this season," say Sir W. Jardine, "or when the pairing has commenced, the birds may be heard piping among the herbage, or may be both seen and heard in the air, performing their evolutions, and uttering the loud drumming sound, which at one time gave rise to so much discussion in regard to the manner in which it was performed. The sound is never heard, except in the downward flight, and when the wings are in rapid and quivering motion; their resistance to the air, without doubt, causes the noise, which forms one of those agreeable variations in a country walk, so earnestly watched for by the practical ornithologist."[7] Mr. Selby compares the sound to the bleating of a goat (a resemblance which has been often noticed), and observes that at this season the bird soars to an immense height, remaining long upon the wing; and that its notes may frequently be heard when the bird itself is far beyond the reach of sight. These flights are performed principally towards the close of day, and are continued during the whole season of breeding. The nest is very slight, consisting of nothing more than a few dry blades of grass or decaying herbage, collected beside a tuft of grass, or merely a scraped hollow. Four eggs are deposited, about an inch and a half in length, of a yellowish or a greenish hue, marked with spots of pale and dark brown, running somewhat obliquely. The young, when hatched, grow very fast, and soon become very large, being often, before they are able to fly, larger than the parents.

Sir Humphrey Davy, who observed many nests of these birds in the month of August, in the Orkneys, remarked that the old birds were much attached to their offspring; and if any one approached they would make a loud and drumming noise above his head, as if to divert his attention from their nest.

Though the Snipe, as we have thus seen, is to a certain extent, a permanent resident in these islands, it is partially migratory also. The numbers of those bred here, are not sufficient to account for the flocks that sometimes appear in August, in which month as many Snipes may often be killed as at any time in the year. Mr. Selby states that great flights come every season from Norway and other northern parts of Europe; arriving in Northumberland in the greatest numbers early in November. They seldom remain long in one situation, moving from place to place, under the influence of various causes, so that the sportsman who has enjoyed excellent Snipe-shooting one day, may find the same spots entirely deserted on the following.

The. food of the Snipe consists of worms, the larvae of insects, small mollusca and crustacea, with which are often taken into the stomach minute seeds, perhaps adhering to their animal food. One kept by Mr. Blyth in confinement would eat only earthworms.[8] Family IV. Palamedeadæ

(Screamers.)

Of this very limited, but widely distributed Family, very little is known. Hence their true affinities and their position in the natural system is still matter of some uncertainty. We follow Mr. G. R. Gray, who, in his "Genera of Birds," elevates them, few as they are in number, to the rank of a Family. Some of them seem modified on the type of the Plovers, and manifest in their anatomy and other points an approach to certain Lapwings; others, again, bear a resemblance to the Gallinacea, with which they have been supposed to connect themselves through the great-footed Megapodidæ. But their strongest affinities are, we think, with the Rallidæ, especially with the genus Porphyrio, which they resemble in their greatly developed toes, their spurred wings, and their habits of walking upon aquatic plants.

The beak is usually slender, rather short, more or less compressed at the sides, and curved downwards at the point. The wing is armed at the shoulder with one or more spurs, of a horny texture, and sharp pointed, which, where most developed, seem to be used as weapons of offence. The feet are long, as are also the legs (tibiæ), the lower portion of which is bare of feathers, and scaled; the toes are four, three before and one behind, the latter resting on the ground; the whole are greatly lengthened, and furnished with exceedingly long, straight, and pointed claws, by the expansion of which the birds are enabled to walk with ease and celerity on the leaves of aquatic plants that float on the surface of rivers and lakes in tropical countries. Their food is believed to consist principally of the seeds and leaves of such plants as grow in the waters.

The tropical regions of South America, Africa, and Asia, are the native countries of these birds, which are found only in the vicinity of large expanses of water.

Genus Palamedea.

The Screamers are large birds which are confined to the hot and teeming forests of South America. They have the beak shorter than the head, covered at the base with small feathers slightly arched, rather high at the base, tapering to the point, where it descends somewhat abruptly. The forehead is armed with a long, slender pointed horn. The nostrils are oval and open. The wings are armed with two spurs, the one large and lancet-shaped, situated on the shoulder, the other a little nearer to the tip; these are firmly fixed on a bony core: the third and fourth quills are the longest. The front toes are united at the base by a small membrane; the hind claw is very long, straight, and sharp: the tarsi are clothed with regular many-sided scales instead of transverse plates.

There is only one ascertained species, the Horned Screamer (Palamedea cornuta, Linn.), called in Brazil the Anhima, and in Guiana the Camichi or Camouche. It is larger than a goose, of a greenish-black hue, variegated on the long neck with white, and marked with a large cinnamon-coloured spot on the shoulder.

This singular bird is an inhabitant of the inundated grounds of South America, where the immense rivers overflowing their banks, cover large

HORNED SCREAMER.

The use of the long, slender, pointed horn with which the Screamer s forehead is furnished, is not apparent : Mr. Swainson believes that it is moveable at the base. There can, however, as Mr. Martin observes, be no possibility of mistaking the use of the shoulder-spurs. Snakes of various size, all rapacious, and all to be dreaded, abound in its haunts, and these formidable weapons enable the bird to defend itself and its young against the assaults of such enemies. If not attacked, however, the Screamer is an inoffensive bird, of shy but gentle manners. The male is contented with a single mate, and their conjugal union is said to be broken only by death.

Some writers have asserted that the Screamer feeds on reptiles; but it would rather appear, that it confines itself to the leaves and seeds of aquatic plants, to obtain which it walks on the matted floating masses of vegetation, or wades in the shallows. Its flight, as might be expected from the length and pointed character of the wings, is sweeping and powerful; on the ground its gait is stately, its head proudly erected, whence, probably, it was regarded by the older travellers, as allied to the Eagle.

The nest of this singular bird is made on the ground at the root of a tree, in which it lays two eggs, resembling those of a goose. The stomach, notwithstanding its vegetable food, is but slightly muscular: the windpipe (trachea) has an abrupt bony box or enlargement about the middle, somewhat like that of the male Velvet Pochard (Oidemia fusca). The loud and piercing character of its voice is doubtless connected with this remarkable structure.

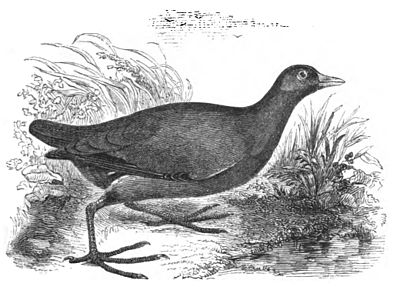

Family V. Rallidæ.

(Rails.)

In the very valuable and elaborate observations of the late Mr. Vigors on the affinities of animals, he remarks that the Rallidæ are separated from the other Families of their Order, and united among themselves, by the shape of their body, which is compressed and flattened on the sides, in consequence of the narrowness of their sternum. "If we were allowed," continues this acute naturalist, "to draw an inference from the analogical construction of other bodies, which move with the greater facility through the water in proportion as they assume this compressed and keel-like form, we might almost conclude that this structure, peculiar to the birds of the present Family, facilitates their progress through that element, and is intended to counterbalance the deficiency in the formation of the foot, which separates them from the truer and more perfectly formed water-birds…… It is certain that the greater portion of these birds are excellent swimmers; and in such habits, as well as in the shortness of their tarsi, which is equally conducive to their powers in swimming, they are found to deviate from all the remaining groups of the Order. They thus become an aberrant Family, and lead directly to the succeeding Order of Natatores [the Anseres of Linn]."[9]

Not less interesting are the remarks of Mr. Swainson on the same subject, especially as they tend to shew a point of affinity, lying in another direction. After observing that the Rails and Water-hens, constituting a very natural Family of Waders, have been designated by these familiar names, from their peculiarly harsh notes, and from assuming much of the appearance of the Gallinaceous birds, another proof that the true analogies of nature are often perceived by the vulgar, though passed over by the scientific,—he thus proceeds:—"The most permanent differences in their structure, when compared with the foregoing Families (those of the Sandpipers and the Plovers), are, the great size of the leg, and the length of the toes, particularly the hinder one; the body is very thin and unusually flattened [vertically]; a structure particularly adapted to the habits of Rails, since they live for the most part in the tangled recesses of those reeds and aquatic vegetables which clothe the sides of rivers and morasses. They are for the most part solitary and timid birds, hiding themselves at the least approach of danger, but quitting their semi-aquatic retreats in the morning and evening, to feed in more open spots: their flight, from the shortness of their wings, is very feeble, but they run with swiftness; and by the peculiarly compressed form of their body, are able to make their way through dense masses of reeds and high grass with so much facility as to escape even after being desperately wounded. The flesh of all these birds is delicate; and from living chiefly upon aquatic seeds and vegetable aliment, they may be considered as aquatic Gallinacea."[10] To these points of resemblance may be added, that many of the species of this Family construct nests of accumulated materials, and lay a great number of eggs.

As in the Family just dismissed, the great length of the toes enables these birds to walk on aquatic herbage without sinking, or on the soft mud and ooze of lakes and morasses. Many swim and dive with a facility not surpassed by that of any of the Ducks, though the feet are not webbed. Some of the most aquatic, however, have a narrow margin of membrane running down each side of the toes, and in one genus this is dilated at intervals, so as to constitute each toe a broad scolloped oar. Flight is rarely resorted to by them as a means of progression or of escaping danger; the posterior limbs are the principal depositories of muscular energy; the sternum is remarkably narrow, the wings short, concave, and moved by feeble muscles; hence the flight, which can be sustained only for a short distance, is slow, heavy, and fluttering; and, during the unwonted exertion, the long legs and feet hang helplessly and awkwardly downward. But on the ground, the close array of tall reeds, or the high grass of the meadow, presents no obstacle to their speed, these they thread with surprising ease; and the bird, which the observer has just seen enter the grassy cover at his feet, he hears almost the next moment at the farthest end of the field, with no indication of its transit, except such as was revealed by a narrow line of motion which shot along the waving surface.

With respect to the other distinctive characters of the Family, we may mention that the beak is in general short, and greatly compressed, frequently running up in a sort of shield upon the forehead; the tail is excessively short, and nearly hidden by the coverts; it is usually carried erect. The toes are all on the same level.

Genus Gallinula. (Briss.)

In this genus the beak is short, compressed, pointed, high at the base, where it ascends on the forehead in a broad shield; the nostrils pervious, and pierced in a wide furrow, in the middle of the beak. Wings short, concave, the second or third quill longest; the shoulder armed with a small spine, not projecting. Legs rather short, strong, naked a little above the heel; feet large; toes long, and rather slender, divided to the base, bordered with a narrow membrane; hind toe comparatively short; claws compressed, very acute. Plumage soft and thick, but loose in texture.

In all our lakes, large ponds, and still rivers, particularly such as are fringed with thick brushwood, or coarse weeds and rushes, the Common Gallinule or Moor-hen (Gallinula chloropus, Linn.) is a well-known bird. It is of a dark olive-brown hue on the upper parts, the head, neck, breast, and sides, dark lead-grey, becoming almost white on the belly: the beak and the feet are green, but the base of the former as well as the forehead-shield, and that part of the leg just above the heel, are bright scarlet.

MOOR-HEN

The Moor-hen may often be seen swimming in the open water of rivers and ponds; which it does with much grace and swiftness, with a nodding motion of the head; it frequently picks floating seeds, shells, or insects, from the surface. It is very wary, and on the approach of an intruder it either dives, or rising just high enough to flap its wings, flutters along the surface with much plashing, to gain the nearest cover. In the former case, it swims a long way beneath the surface before it rises again, aiding its progress by striking vigorously not only with the feet, but also with the short and hollow wings, which are expanded. The whole plumage, when immerged, is coated with a thin pellicle of air, which has a singular and beautiful effect. In a small cover, if it suspect the continuance of danger, it will remain beneath the water for an incredible space of time, probably holding fast by the stalks or roots of the sedges.

With all its native shyness and susceptibility of alarm, the Moor-hen soon learns to disregard intrusion, when it finds that no danger accrues, and becomes tame and confiding. Pennant speaks of a pair in his grounds, which never failed to appear when he called his ducks to be fed, and partook of their corn in his presence. Mr. Yarrell observes that among the many aquatic birds with which the Ornithological Society have stocked the canal and the islands in St. James's Park, are several Moor-hens; in the course of the summer of 1841, two broods were produced, the young of which were so tame that they would leave the water and come up on the path, close to the feet of visitors, to receive crumbs of bread.

The fry of fishes, water-insects and their larvæ, especially the grubs of the larger Dragon-flies, water-snails, and crustacea, as well as the seeds of aquatic plants, afford food to the Moor-hen in its more proper element; but it seeks analogous substances on the land also, walking on the grassy borders of lakes, or through the low-lying meadows, at morning and evening dusk, particularly after warm rains. In winter they perhaps find other resources, as suggested in the following interesting note by Mr. Jesse. "The disappearance of Water-hens from ponds during a hard frost has often surprised me, as I could not make out where they were likely to go for food and shelter when their natural haunts were frozen over. When the ice has disappeared, the birds have returned. I have lately discovered, however, that they harbour in thick hedges and bushes, from which they are not easily driven; aware, probably, that they have no other shelter. They also get into thorn-trees, especially those covered with ivy, and probably feed on the berries, although their feet seem but ill-adapted for perching. During a very severe frost, a pair of Water-hens kept almost entirely in a large arbutus-tree on a lawn, which was inclosed by a high paling, and had no pond near it. Here they probably fed on the berries of the tree, and the other produce of the garden."[11]

The nest of this bird is composed of dry rushes, grass, or other coarse materials accumulated in considerable quantity among reeds or herbage, near the water's-edge; sometimes on the low branch of a tree which droops into the stream. In the "Naturalist," a case is recorded in which the nest floated on the water without any attachment whatever to the island which it adjoined, but was inclosed on all sides by sticks, &c. Thus situated, the careful parents hatched their eggs in perfect safety; though, had the water risen to an unusual height, the case might have been otherwise.

Curious instances of sagacity, or what one would call presence of mind, in this bird's behaviour when danger threatens her eggs or infant-brood, are on record, from which we select the following. The charming writer already quoted, Mr. Jesse, observes,— "The Moor-hen displays some-times a singular degree of foresight in her care for her young. It is well known that she builds her nest amongst sedges and bulrushes, and generally pretty close to the water, as it is there less likely to be observed. In places, however, where anything like a flood is likely to take place, a second nest, more out of the reach of the water, is constructed, which is intended to be in readiness in case a removal of the eggs or young ones should be found necessary. This observation was made by a family residing at an old priory in Surrey, where Moor-hens abound, and where the fact was too often witnessed by themselves and others, to leave any doubt upon their minds."[12]

"During the early part of the summer of 1835," observes Mr. Selby, "a pair of Water-hens built their nest by the margin of the ornamental pond at Bell's Hill, a piece of water of considerable extent, and ordinarily fed by a spring from the height above, but into which the contents of another large pond can occasionally be admitted. This was done while the female was sitting; and as the nest had been built when the water-level stood low, the sudden influx of this large body of water from the second pond caused a rise of several inches, so as to threaten the speedy immersion and consequent destruction of the eggs. This the birds seem to have been aware of, and immediately took precautions against so imminent a danger; for when the gardener, upon whose veracity I can safely rely, seeing the sudden rise of the water, went to look after the nest, expecting to find it covered, and the eggs destroyed, or at least forsaken by the hen, he observed, while at a distance, both birds busily engaged about the brink where the nest was placed; and when near enough, he clearly perceived that they were adding, with all possible despatch, fresh materials to raise the fabric beyond the level of the increased contents of the pond, and that the eggs had, by some means, been removed from the nest by the birds, and were then deposited upon the grass, about a foot or more from the margin of the water. He watched them for some time, and saw the nest rapidly increase in height; but I regret to add, that he did not remain long enough, fearing he might create alarm, to witness the interesting act of the replacing of the eggs, which must have been effected shortly afterwards; for upon his return, in less than an hour, he found the hen quietly sitting upon them in the newly-raised nest. In a few days afterwards, the young were hatched, and, as usual, soon quitted the nest, and took to the water with their parents. The nest was shewn to me in situ very soon afterwards, and I could then plainly discern the formation of the new with the older part of the fabric."[13]

The young soon display a good deal of sagacity in avoiding danger, and in obeying the monitory signals of their watchful parents. Mr. Rennie says that he has seen a young brood, evidently not above two days old, dive instantaneously, even before the watchful mother seemed to have time to warn them of his approach, and certainly before she followed them under water.[14] And Mr. Jesse, having disturbed a Moor-hen that had just hatched, tells us that " her anxiety and manoeuvres to draw away her young were singularly interesting. She would go a short distance, utter a cry, return, and seemed to point out the way for her brood to follow. Having driven her away," he continues, "that I might have a better opportunity of watching her young ones, she never ceased calling to them, and at length they made towards her, skulking amongst the rushes, till they got to the other side of the pond. They had only just left the shell, and had probably never heard the cry of their mother before."[15]

The young have the legs and feet of their full size and development, while the feathers of the wings are only beginning to protrude; thus proving how subordinate the organs of flight in this genus are to those of walking and swimming. Contrary to what is usual among birds, the female Gallinule is more richly adorned than the male; the plumage being of a deeper colour, and the frontal shield being larger, and of a brilliant scarlet, like sealing-wax, while that of the other sex is of a dull brown.

- ↑ Jardine.

- ↑ Nat. Lib. Ornithology, iii 282.

- ↑ Yarell's Brit. Birds, ii 482.

- ↑ We believe the Herons never take or hold their prey with the foot.

- ↑ Anim. Nature, iii. 263, 264.

- ↑ Brit. Birds, iii. 29.

- ↑ Nat. Lib. Ornithology, iii. 180.

- ↑ Yarrel's Brit. Birds, iii. 30.

- ↑ Linn. Trans. vol. xv.

- ↑ Classification of Birds.

- ↑ Gleanings, p. 303

- ↑ Gleanings, p. 215.

- ↑ Proceedings of Berwicksh. Naturalists' Club.

- ↑ Habits of Birds, p. 216.

- ↑ Gleanings, p. 53.