CHAPTER III

The Coleoptera.

The observations on the natural history of the New Zealand beetles, forming the subject of the present chapter, are much less numerous than might have been expected from the great number of species which have been described. The difficulties attendant on rearing these insects are, however, very great, and it thus happens that the life-histories here given bear a smaller proportion to the number of the Coleoptera than will be found to be the case with the majority of the other Orders. I hope, however, that the few details I have collected, referring to the following species, may induce some of my readers to investigate others for themselves.

Group Geodephaga.

Family Cicindelidæ.

Cicindela tuberculata (Plate I., fig. 1, 1a larva).

This is a very abundant insect found throughout the country in all dry situations. It delights in hot sunshine, and may be constantly observed flying from our footsteps with great rapidity as we walk along the roads on a hot summer's day.

Its larva (Fig. 1a) is an elongate fleshy grub, the head and first segment being horny and much flattened, and the body provided with two large dorsal humps, each bearing at its apex a slender curved hook.

The burrows of these insects are very conspicuous, and must have been noticed by every one, in garden paths, sandbanks, and other dry situations; they are sometimes very numerous, and may be best described as perfectly round shafts, about one line in diameter, and extending to the depth of three or four inches, generally slightly curved at the bottom. The sides are perfectly smooth, and the larva may be often discovered near the mouth of its burrow, using its dorsal hooks to support it, and thus having both legs and jaws free to dispose of the unfortunate insects that fall into its snare. These usually consist of flies and small beetles, which appear to be urged by curiosity to crawl down these pitfalls, and thus bring about their own destruction. By reference to the figure it will be seen how admirably the hollowed head and prothorax serve the purpose of a shovel to the larva, when forming its shaft. These burrows are first observed about the middle of November; the perfect insects coming abroad three weeks or a month later, when they may be often seen in the neighbourhood of their old domiciles. They are very voracious, devouring large quantities of flies, caterpillars, and other insects, some of which are much superior to themselves in size. On one occasion I saw a male specimen of Cicindela parryi (a species closely allied to but smaller than C. tuberculata) attack a large Tortrix caterpillar, an inch and a half in length. The beetle invariably sprang upon the back of the caterpillar and bit it in the neck, being meanwhile flung over and over by the larva's vigorous efforts to free itself from so unpleasant an assailant. During the fight, which lasted fully twenty minutes, the beetle was compelled to retire periodically to gain fresh strength to renew its attacks, which were eventually successful, the unfortunate tortrix becoming finally completely exhausted. The beetle devoured but a very small portion of the caterpillar, and abandoning the remainder went off in search of fresh prey. Eight other closely allied species of Cicindela are described by Captain Broun in the "Manual of the New Zealand Coleoptera," but they offer no especial peculiarities, and C. tuberculata may be taken as a type of the genus.

Family Carabidæ.

Pterostichus opulentus (Plate I., fig. 3, 3a larva).

This fine beetle is very common in most wooded situations in the Nelson district; it may be at once distinguished from the numerous other closely allied species by the beautiful metallic coppery tints that adorn its thorax and elytra.

During the day it is usually discovered concealed under logs and stones, and when disturbed, rushes into the first crevice to get out of the light. At night time, it comes abroad to feed, killing an immense number of flies, caterpillars, and other insects, to satisfy its voracious appetite. Although of a most ferocious disposition, it is not wanting in maternal affection. The female, when about to deposit her eggs, excavates a small cavity nearly three inches square, in which they are placed. These she broods over until hatched, and probably some little time afterwards, as I have found a specimen close to a nest, which contained both eggs and larvæ, and the zealous mother furiously bit at anything presented to her. The eggs are oval in shape, quite smooth, and yellowish white in colour. The young larva is drawn at Plate I., fig. 3a; it is remarkable for its superficial resemblance to a small Iulus, and being found in similar situations to that animal, its mimicry has probably some useful object. The older larva differs chiefly in having the head and thoracic segments proportionately smaller. Twenty-one closely allied insects belonging to two genera are described by Captain Broun in his Manual, the largest being Pterostichus australasiæ, which is found in similar localities to the present species, but is not so common.

Group Hydradephaga.

Family Dyticidæ.

Colymbetes rufimanus (Plate I., fig. 4, 4a larva).

This insect is found plentifully in all still waters during the summer months. Its larva is a soft elongate grub, provided with six slender thoracic legs, and a pair of powerful mandibles. The posterior extremity of the body is furnished with two curious appendages bearing a spiracle at the apex of each, which the larva frequently protrudes above the surface of the water. The air is taken in through the spiracles, and conveyed to all parts of the body by two main air-tubes, one of which springs from each spiracle, and branches throughout the insect in every direction. During the spring months the larvæ may be found of various sizes in similar situations to the imago; they are very voracious, devouring freshwater shrimps, Ephemera larvæ, and occasionally, when pressed by hunger, they will even destroy individuals of their own species for food. These they capture by means of their powerful mandibles, retaining a firm hold of the victim until they have consumed all the fleshy portions, the rest of the carcase being thrown aside, and a fresh search made for more. One individual I kept for some time, remained perpetually concealed in a small patch of green weed, growing in the middle of its aquarium. In a short time it became surrounded with the skeletons of small water shrimps which had been seized by the larva as they passed by its hiding place, the unfortunate crustaceans only discovering their enemy when it was too late. I have not yet observed the pupa of this insect, but it probably does not differ materially from those of its European allies. Although so very different in general appearance to the preceding insects, this beetle will be found on careful examination to agree with them in all important respects, being only what a ground beetle might naturally become if forced to lead an aquatic existence. Breathing is effected in all the water beetles by the spiracles of the abdomen, which alone are developed. The air is taken in between the elytra and the body, and owing to the convexity of the former, a supply can be retained sufficient to last the insect some twenty or thirty minutes. The beetles may be often observed with the extremity of their elytra protruded above the surface, renewing their supplies of air. On very hot days C. rufimanus may be occasionally seen flying with great rapidity far away from its native ponds. When doing so it makes a loud humming noise, and is a much more conspicuous object than when in the water.

Group Clavicornia.

Family Nitidulidæ.

Epuræa zealandica.

This curious little beetle is found abundantly in the neighbourhood of decaying fungi, throughout the year, being most plentiful in the autumn and early winter. Its larva is a small cylindrical grub, with the head and legs so minute that they are scarcely perceptible, causing it to closely resemble the maggots of many dipterous insects, occurring in similar localities. It is generally found in the large yellow fungi, so abundant in wet situations during the late autumn and winter months. It forms numerous galleries through the plant in all directions, and owing to the large amount of moisture which is usually present, these galleries are often filled with water, so that the insect may be said to be sub-aquatic in its habits. I have not yet detected the pupa of this species, although the discovery of a large quantity of both larvæ and perfect insects is of everyday occurrence with the entomologist in winter.

Family Engidæ.

Dryocora Howittii (Plate I., fig. 6, 6a larva).

This quaint-looking little insect occurs occasionally in damp matai logs, when in an advanced state of decay. The larva (Fig. 6a) is very flat and thin, possessing the usual thoracic legs, which, however, are rather short. The last segment of the abdomen is furnished with an anal proleg and a pair of small setiform appendages. Its mode of progression is very peculiar, resembling that of the Geometer larvæ among the Lepidoptera.

The thoracic legs are first brought to the ground, and the rest of the body is then drawn up in an arched position close behind them. The anal proleg then supports the insect while the anterior segments are thrust out, and the others follow as before. This method is only employed on smooth surfaces, the larva crawling along elsewhere in the usual manner.

The perfect beetle is a very sluggish insect, and difficult to find owing to its colour, which closely resembles that of the wood in which it lives.

Family Engidæ.

Chætosoma scaritides (Plate I., fig. 2).

This insect may be at once recognized by its peculiar shape, no other New Zealand beetle resembling it in this respect. Although tolerably common and generally distributed, it is very seldom seen abroad, spending almost the whole of its life concealed in the burrows of various wood-boring weevils. Its larva, which feeds on the grubs of these insects, is of a pinkish colour, very fat and sluggish; the head and three anterior segments are strong and horny, the legs being rather short. It undergoes its transformation into the pupa within the weevil burrows, when the limbs of the perfect insect can be seen folded down the breast, the wings and elytra being much smaller than in the beetle. Specimens in all stages of existence may be readily procured by splitting up old perforated logs which have been long tenanted by weevils.

Group Brachelytra.

Family Staphylinidæ.

Staphylinus oculatus (Plate I., fig. 5).

This is the New Zealand representative of S. olens or the "Devil's Coach Horse," one of the most familiar of British beetles. It is found occasionally in the neighbourhood of slaughter-houses, and may be at once distinguished from any of the allied species by a large spot of brilliant scarlet situated on each side of its head behind the eyes; this very conspicuous feature has given it the specific name of oculatus. I am at present unacquainted with the transformations of this fine insect, but they will probably closely resemble those of the typical species (S. olens) described in the majority of standard books on European Coleoptera. This beetle may be frequently seen flying in the sunshine, when it has a most striking appearance, owing to its large size and rapid motion. An unpleasant odour is found to arise when it is handled, this being noticeable in nearly all the members of the family. These beetles are comparatively numerous in New Zealand, the genus Philonthus comprising several elongate active insects, of which P. œneus is one of the commonest, and may be found abundantly amongst garden refuse. Others frequent the seashore, feeding on decaying seaweed, and may be noticed flying in all directions along the coast immediately after sundown. Another genus (Xantholinus) includes a number of interesting beetles found in old weevil burrows, and probably feeding on their inmates.

Group Lamellicornes.

Family Lucanidæ.

Dorcus punctulatus (Plate I., fig. 7).

An abundant species chiefly attached to the red pine tree or rimu, where it may be found concealed beneath the scaly bark, in the angles of the trunk near the roots. When disturbed, it folds up its legs and antennæ on its breast, and, extending its powerful jaws, awaits the approach of the enemy, ready to bite anything coming within its reach. These, however, are purely defensive measures, the insect being quite harmless when left alone. The larva is at present unknown to me. Another species, D. reticulatus, is a much handsomer insect than the preceding; it may be at once recognized by four deep impressions in the thorax, filled in with light-brown scales; the margins of the elytra are similarly scaled, as well as four spots on each elytron, the remainder of the beetle being dark-brown and shining. It is generally found in totara bark, but is much scarcer than the last species. One small specimen I possess, remarkable for its brilliant appearance, was taken under the bark of a stunted black birch tree, over two thousand feet above the sea-level.

Family Melolonthidæ.

Stethaspis suturalis (Plate I., fig. 8, 8a larva).

This conspicuous insect occurs abundantly in all open situations. Its larva (Fig. 8a) inhabits the earth, feeding on the roots of various plants, and is especially abundant in paddocks, where it occasionally does considerable damage to the grass, and threatens ere long to become as great a pest as its first cousin, the renowned Cockchaffer of England (Melolontha vulgaris), whose fearful ravages need no description. It may be taken as a typical larva of the family, the rest differing from one another in little else than size. When full-grown it is quite as large as the illustration, and is nearly always in the position there indicated, owing to the size of its posterior segments and the absence of any anal proleg, which compel it to lie always on its side. I have not yet succeeded in obtaining the pupa of this insect, although larvæ may be frequently found enclosed in oval cells, evidently about to undergo their transformation. Several of these have been kept in captivity, but they have hitherto always died without undergoing any change. I have, however, no doubt as to its being the larva of S. suturalis, as there are no other large Lamellicorns found near Wellington to which it could possibly be referred. The perfect beetle appears in great numbers from November to March; it is best taken at dusk, when it flies with a loud humming noise, about four feet above the ground. If knocked down it always falls amongst the herbage, and is not readily perceived until a few minutes later, when the humming noise is resumed as the insect again gets under weigh, and the would-be captor must not lose time if he wishes to secure it. Occasionally individuals are seen disporting themselves on the wing during the day, but this must be regarded as a purely exceptional circumstance. Unlike the majority of nocturnal Coleoptera, this insect does not appear to be attracted by light; in fact I have never obtained any specimens by this method, although most other night-flying beetles may be taken in goodly numbers at the attracting lamp.

Family Melolonthidæ.

Pyronota festiva.

This brilliant little insect is extremely abundant amongst manuka, during the early summer. In general appearance it reminds one of a miniature specimen of the last species, but is more elongate in form; the green thorax and elytra are also much brighter. The latter are bordered with flashing crimson, the legs and under surface being reddish-brown, sparsely clothed with white hairs. A small Lamellicorn grub, found amongst refuse in manuka thickets, is probably the larva of this insect; it is less thickened posteriorly than that of S. suturalis, but otherwise closely resembles it. The perfect insect is diurnal in its habits, flying round flowering manuka in countless numbers on a hot day. The descent of thirty or forty of these little beetles on to the beating sheet, out of a single bush, is of frequent occurrence, and is particularly noticed by the New Zealand entomologist accustomed to the meagre supply of specimens offered in the majority of instances.

Group Sternoxi.

Family Elateridæ.

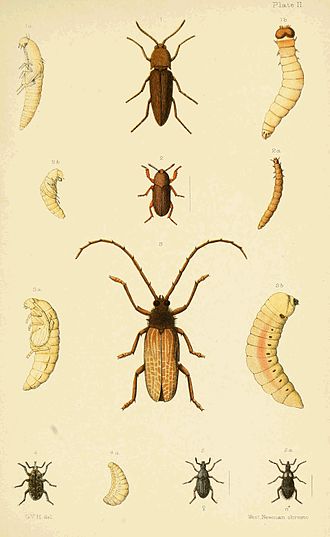

Thoramus wakefieldi (Plate II., fig. 1, 1b larva, 1a pupa).

This fine beetle may be taken under rimu bark in tolerable abundance, and is often observed flying about at dusk during the summer. Its larva inhabits rotten wood, usually selecting the red pine, in which it excavates numerous flat galleries near the surface of the logs. When disturbed it is very sluggish, the head being immediately withdrawn into the large thoracic segment and completely concealed. The legs are very minute, and are of but little use in walking, the insect being chiefly dependent for locomotion on its large anal proleg, which is furnished with numerous horny spines. When full-grown this larva closes up one end of its burrow, and thus forms a closed cell, in which it is transformed into the pupa shown at Fig. 1a, remaining in this condition until the warmer weather calls the insect from its retreat. Two closely allied species are T. perblandus and Metablax acutipennis. The former is occasionally found under the large scales on matai trees, and resembles the present insect in general appearance, but is much smaller and more elongate in form, its elytra being also ornamented with longitudinal rows of yellowish-brown hairs. The latter may be often taken on the wing in the hottest sunshine, and is chiefly remarkable for its elongate prothorax and pointed elytra; its colour is dark reddish-brown, ornamented with a few scattered white hairs. All these insects possess the singular habit of leaping into the air when placed on their backs, the last-named species exercising this faculty in a most marked degree. The movement is effected by the joint between the pro- and meso-thorax, the sternum of the former being elongated into a long process, fitting into a corresponding cavity in the latter, so that by means of the two being suddenly brought together, the insect is thrown high into the air with a loud clicking sound, hence the English name of the Skipjack or Click Beetles, the scientific name, Elater, doubtless having reference to the same habit. The object of this curious arrangement is in all probability twofold; the sharp click and rapid movement of the insect deterring many enemies from attacking it, whilst the short legs of the beetle, which are quite unable to reach the ground when it is thrown on its back, render a special contrivance necessary.

Group Heteromera.

Family Tenebrionidæ.

Uloma tenebrionides (Plate II., fig. 2, 2a larva, 2b pupa).

One of our commonest beetles, found in great abundance in all moist wood when much decayed, the favourite trees being apparently rimu and matai. Its cylindrical larva may be taken in similar situations, and much resembles in general appearance the well-known "wire-worm" of England, whose destructive habits, however, it does not share. At present, whilst bush-clearing is going on, its influence is beneficial, as it devours large quantities of useless wood, which is thus rapidly broken up and got rid of. The pupa is enclosed in an oval cell, constructed by the larva before changing, from which the perfect insect emerges in due course. When first exuded its colour is pale red, but this rapidly changes into dark brown after the insect has been hardened by exposure to the air. Specimens are often met with of every intermediate shade, and are rather liable to deceive the beginner, who mistakes them for distinct species. An account of a small Dipterous insect infesting this beetle in its preparatory states will be found on page 62.

Group Longicornia.

Family Prionidæ.

Prionus reticularis (Plate II., fig. 3, 3b larva, 3a pupa).

This is the largest species of beetle found in New Zealand, and is common throughout the summer in the neighbourhood of forests. Its larva (Fig. 3b) is a large, fat grub, with minute legs; it inhabits rimu and matai, logs, often committing great ravages on sound timber although frequently eating that which is decayed; posts, rails, and the rafters of houses alike suffer from its attacks; the great holes formed by a full-grown larva of this insect creating rapid destruction in the largest timbers. It may be remarked, in connection with these wood-boring species, that a good thick coat of paint put on the timber as soon as it is exposed, and renewed at frequent intervals, to a great extent prevents their attacks. The pupa (Fig. 3a) is enclosed in one of the burrows formed by the larva, which, before changing, blocks up any aperture, so as to rest secure from all enemies. The perfect insect emerges in the following summer, when it may be often observed flying about at night. It is greatly attracted by light, and this propensity frequently leads it on summer evenings to invade ladies' drawing-rooms, when its sudden and noisy arrival is apt to cause much needless consternation amongst the inmates.

Closely allied to the above is Ochrocydus huttoni, which may be at once known by its smaller size and plain elytra; it is very much scarcer than P. reticularis, but may occasionally be cut out of dead manuka trees in company with its larva.

Group Rhyncophora.

Family Curculionidæ.

Oreda notata (Plate II., fig. 4, 4a larva).

This weevil is not often noticed in the open, but may be found in great abundance in the dead stems of fuchsia, mahoe, and other soft-wooded shrubs, whose trunks are frequently noticed pierced with numerous cylindrical holes. The larva also inhabits these burrows, devouring large quantities of the wood; it is provided with a large head and powerful pair of mandibles, but, in common with all other weevil larvæ, does not possess legs of any description, the insect being absolutely helpless when removed from its home in the wood. The pupa might also be found in similar situations, but I have not yet observed it. The perfect insect may be cut out of the trees throughout the year, and is occasionally taken amongst herbage during the summer.

Family Curculionidæ.

Psepholax coronatus (Plate II., fig. 5 ♀, 5a ♂).

This curious species is found abundantly in the stems of dead currant trees (Aristotelia racemosa), in which it excavates numerous cylindrical burrows like the last species, which it closely resembles when in the larval state. The sexes are widely different, the elytra of the male being furnished with the characteristic coronet of spines, which is entirely wanting in the female. Numerous other members of this genus may be taken in company with the present insect, and should be carefully examined, as a correct determination of the males and females of the several species is sadly wanted. Digging beetles out of the wood is good employment for the entomologist in winter, when he will find that a day spent in this manner will frequently produce as rich a harvest as one in the height of summer.

Before finally leaving the Coleoptera, I should like to direct the attention of my readers to the immense number of interesting weevils found in New Zealand. Chief among these is the remarkable Lasiorhynchus barbicornis, a large insect furnished with a gigantic rostrum, which will at once distinguish it from any of the rest. Other genera contain numerous beetles, which may be found in various kinds of dead timber in company with their larvæ, and are worthy of a more minute investigation than has at present been given them.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||