Once a Week (magazine)/Series 1/Volume 1/A good fight - Part 8

A Good Fight.

BY CHARLES READE.

CHAPTER XV.

“I hope ’tis the Burgomaster that carries the light,” said the escaped prisoner, panting with a strange mixture of horror and exultation. The soldier, he knew, would send an arrow through a burgher or a burgomaster, as he would through a boar in a wood.

But who may foretell the future, however near? The bow instead of remaining firm, and loosing the deadly shaft, was seen to waver first, then shake violently, and the stout soldier staggered back to them, his knees knocking and his cheeks blanched with fear. He let his arrow fall, and clutched Gerard’s shoulder.

“Let me feel flesh and blood,” he gasped: “the haunted tower! the haunted tower!”

His terror communicated itself to Margaret and Gerard. They could hardly find breath to ask him what he had seen. “Hush!” he cried, “it will hear you. Up the wall! it is going up the wall! Its head is on fire. Up the wall, as mortal creatures walk upon green sward. If you know a prayer say it! For hell is loose to-night.”

“I have power to exorcise spirits,” said Gerard, trembling. “I will venture forth.”

“Go alone, then!” said Martin, “I have looked on’t once and live.”

Gerard stepped forth, and Margaret seized his hand and held it convulsively, and they crept out.

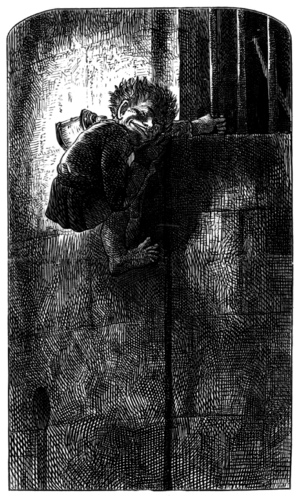

Sure enough a sight struck their eyes that benumbed them as they stood. Half-way up the tower, a creature with fiery head, like an enormous glow-worm, was going steadily up the wall: the body was dark, but its outline visible, and the whole creature not much less than four feet long. At the foot of the tower stood a thing in white, that looked exactly like the figure of a female. Gerard and Margaret palpitated with awe.

“The rope—the rope! It is going up the rope—not the wall,” gasped Gerard.

As they gazed, the glow-worm disappeared in Gerard’s late prison, but its light illuminated the cell inside and reddened the window. The white figure stood motionless below. Such as can retain their senses after the first prostrating effect of the supernatural, are apt to experience terror in one of its strangest forms, a wild desire to fling themselves upon the terrible object. It fascinates them as the snake the bird. The great tragedian Macready used to render this finely in Macbeth at Banquo’s second appearance. He flung himself with averted head at the horrible shadow. This strange impulse now seized Margaret. She put down Gerard’s hand quietly, and stood fascinated; then, all in a moment, with a wild cry, darted towards the spectre. Gerard, not aware of the natural impulse I have spoken of, never doubted the evil one was drawing her to her perdition. He fell on his knees.

“Exorcizo vos. In nomine beatæ Mariæ, exorcizo vos.”

While he was shrieking his incantations in extremity of terror, to his infinite relief he heard the spectre utter a feeble cry of fear. To find that hell had also its little weaknesses was encouraging. He redoubled his exorcisms, and presently he saw the shape kneeling at Margaret’s knees, and heard it praying piteously for mercy.

Poor little spectre! It took Margaret for the ill spirit of the haunted tower, come flying out on it—to damn it.

Kate and Giles soon reached the haunted tower. Judge their surprise when they found a new rope dangling from the prisoner’s window to the ground.

“I see how it is,” said the inferior intelligence taking facts as they came. “Our Gerard has come down this rope. He has got clear. Up I go, and see.”

“No, Giles, no!” said the superior intelligence blinded by prejudice. “See you not this is glamour. This rope is a line the evil one casts out to wile you to destruction. He knows the weaknesses of all our hearts; he has seen how fond you are of going up things. Where should our Gerard procure a rope? how fasten it in the very sky like that? It is not in nature. Holy saints protect us this night, for hell is abroad.”

“Stuff!” said the dwarf: “the way to hell is down, and this rope leads up. I never had the luck to go up such a long rope. It may be years ere I fall in with such a long rope all ready fastened for me. As well be knocked on the head at once as never know enjoyment.”

And he sprung on to the rope with a cry of delight, as a cat jumps with a mew on a table where fish is. All the gymnast was on fire; and the only concession Kate could gain from him was permission to fasten the lantern on his neck first.

“A light scares the ill spirits,” said she.

And so, with his huge arms, and legs like feathers, Giles went up the rope faster than his brother came down it. The light at the nape of his neck made a glow-worm of him. His sister watched his progress with trembling anxiety. Suddenly a female figure started out of the solid masonry, and came flying at her with more than mortal velocity.

Kate uttered a feeble cry. It was all she could, for her tongue clove to her palate with terror. Then she dropped her crutches, and sank upon her knees, hiding her face and moaning:

“Take my body, but spare my soul!” &c.

Margaret (panting). “Why it is a woman!”

Kate (quivering). “Why it is a woman!”

Margaret. “How you frightened me.”

Kate. “I am frightened enough myself. Oh! oh! oh!”

“This is strange. But the fiery-headed thing! Yet it was with you, and you are harmless. But why are you here at this time of night?”

“Nay, why are you?”

“Perhaps we are on the same errand? Ah! you are his good sister, Kate.”

“And you are Margaret Brandt.”

“Yes.”

“All the better. You love him: you are here. Then Giles was right. He has escaped.”

Gerard came forward, and put the question at rest. But all further explanation was cut short by a horrible unearthly cry, like a sepulchre exulting aloud:

“Parchment! Parchment! Parchment!”

At each repetition it rose in intensity. They looked up, and there was the dwarf with his hands full of parchments, and his face lighted with fiendish joy, and lurid with diabolical fire. The light being at his neck, a more infernal “transparency” never startled mortal eye. With the word the awful imp hurled the parchment down at the astonished heads below. Down came the records, like wounded wild ducks, some collapsed, others fluttering, and others spread out and wheeling slowly down in airy circles. They had hardly settled, when again the sepulchral roar was heard: “Parchment!—Parchment!” and down pattered and sailed another flock of documents—another followed: they whitened the grass. Finally, the fire-headed imp, with his light body and horny hands, slid down the rope like a falling star, and (business before sentiment) proposed to Gerard an immediate settlement for the merchandise he had just delivered.

“Hush!” said Gerard; “you speak too loud. Gather them up and follow us to a safer place than this.”

“Will you not come home with me, Gerard?”

“I have no home.”

“You shall not say so, Gerard. Who is more welcome than you will be, after this cruel wrong, to your father’s house?”

“Father? I have no father,” said Gerard, sternly. “He that was my father is turned my gaoler. I have escaped from his hands; I will never come within their reach again.”

“An enemy did this, and not our father,” said Kate.

And she told him what she had overheard Cornelis and Sybrandt say. But the injury was too recent to be soothed. Gerard showed a bitterness of indignation he had hitherto seemed incapable of.

“Cornelis and Sybrandt are two ill curs that have shown me their teeth and their heart a long while; but they could do no more. My father it is that gave the Burgomaster authority, or he durst not have laid a finger on me, that am a free burgher of this town. So be it, then. I was his son—I am his prisoner. He has played his part—I shall play mine. Farewell the town where I was born and lived honestly, and was put in prison. While there is another town left in creation, I’ll never trouble you again, Tergou.”

“Oh, Gerard! Gerard!”

Margaret whispered her:—“Do not gainsay him now. Give his choler time to cool!”

Kate turned quickly towards her. “Let me look at your face!” The inspection was favourable, it seemed, for she whispered:—“It is a comely face, and no mischief-maker’s.”

“Fear me not,” said Margaret, in the same tone. “I could not be happy without your love as well as Gerard’s.”

“These are comfortable words,” sobbed Kate. Then, looking up, she said, “I little thought to like you so well. My heart is willing, but my infirmity will not let me embrace you.”

Page:Once a Week Jul - Dec 1859.pdf/164 Page:Once a Week Jul - Dec 1859.pdf/165 Page:Once a Week Jul - Dec 1859.pdf/166