Once a Week (magazine)/Series 1/Volume 5/An artist's ramble along the line of the Picts' wall - Part 4

AN ARTIST’S RAMBLE ALONG THE LINE OF THE PICTS’ WALL.

PART IV.

Sampson Erdeswicke, who wrote concerning the wall as early as 1574, says: “The Scotts lyches, or surgeons, do yerely repayr to the sayd Roman wall next to thes (Cær Vurron) to gether sundry herbs for surgery, for that it is thought that the Romaynes there by had planted most nedefull herbes for sundry purposes, but howsoever it was, these herbes are fownd very wholesome.”

Near the wall, and on the eastern declivity of the defile, is a spring, popularly called King Arthur’s Well, but, by another tradition, it is understood to have been the well in which King Ecfrid was baptised by the Missionary Paulinus. We took a draught of the water, which is cool and pure.

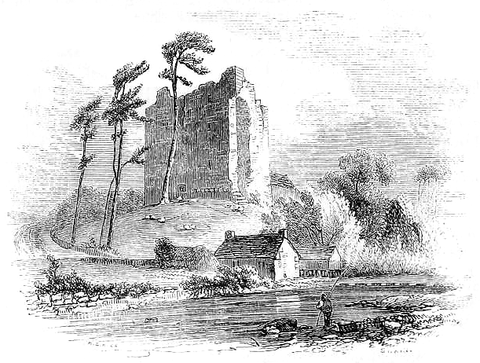

On the western side of the gap the acclivity is very steep. Hutton says he had to climb it on all-fours. On the summit are traces of a mile castle. We now had before us a series of indented crags, called the Nine Nicks of Thirlwall; along these abrupt eminences the wall appears in great preservation, and, in some places, it presents to the north a height of nearly nine feet, the thickness being nine feet; here we counted twelve courses of facing-stones. Hence the cliffs gradually subside, and a more cultivated region appears as we approached Caervoran—the Roman Magna. The station comprehends an area of four acres and a-half. It stands upon a platform, with a steep declivity on the southern side towards the village of Glenwhelt. This situation appears to have been planned in order to avoid a bog which, had the station been set as usual next to the wall, must have intercepted the vallum. The latter avoids the bog by running close to the wall, which is carried along a ridge of elevated ground. Some fragments only of the north rampart and the fosse on the same side remain. We now descended to our quarters at Glenwhelt, where, in the inn, are preserved a magnificent pair of antlers found in a well at the station.Here, after a seemly libation, we took leave of W, and, having rested, strolled by the banks of Typalt Burn to the dark and shattered walls of Thirlwall Castle, whose name is supposed to have been derived from the Scots having broken through the neighbouring barrier in one of their aggressions on the southrons.

The walls of the castle are of the great thickness of nine feet, and the facings are composed of stones taken from the Roman wall. I may here remark that for ages the wall appears to have been appropriated for every kind of erection built near it. The materials for farmhouses, cottages, and dry stone dykes, have been so abundantly quarried from it, that the only marvel is that any part of it should remain; but the larger vestiges appear chiefly in craggy and barren solitudes, the abode only of the curlew and the hill-fox.

After the dispatch, on the following morning, of such a breakfast as only pedestrians enjoy

we set forth for Gilsland, our next quarters, stopping as we sallied forth to pay our respects to the colossal head, which stands in all its grotesque ugliness upon the wall in front of the inn, its ludicrous effect being enhanced by the top of a quern, which some pious hand has clapped on it, after the manner of a Scot’s bonnet. Between the waters of the Typalt and the Irthing, the wall traverses a flat and exposed surface, and here the vallum has closely accompanied it, but of the wall within this space there is no superficial appearance till arriving at the small village of Wallend, about half a mile no. Here the two lines of defence change their relative positions; the wall, pursuing a lower level, is entirely commanded by the earthworks of the vallum, until the river Irthing is attained.

Arriving at the Shaw’s hotel we only stopped to bespeak our dormitories, and take needful refreshments, which, being accomplished to our full satisfaction, we proceeded on our way, and, crossing the Poltross Burn, stood on Cumbrian ground. Here, after having climbed the steep precipice on the opposite side of the burn, we again fell in with the wall and vallum, and the vestiges of a mile castle, and, after an escape from an angry bull, approached Burdoswald, a name which is accounted for by the tradition that Oswald, King of Northumbria, had a hunting-seat here, and was here seized while alone and fishing in the waters of the Irthing by a band of northern freebooters.

Burdoswald—the Roman Amboglanna—is the twelfth station on the wall. It comprehends an area of between five and six acres. Having been ably excavated in 1850 by Mr. H. Norman, the proprietor of the camp, and Mr. Potter, its parts are clearly defined, and it is justly considered one of the most perfect stations along the whole line of the wall. A greater number of inscribed stones have been found here than in any other station on this line—and from these it appears, according to Horsley (Brit. Rom. 257) that about the middle of the third century, the Cohors Prima Eliana Dacorum was here stationed. The derivation of the name Amboglanna has been the subject of different conjectures, the most likely of which appears to be that derived from the Latin word ambo, and the British glan, the brink or bank of a river, which agrees exactly with the situation of the camp, standing as it does upon a point of land, with the steep banks of the Irthing on either hand of it. Beginning with the west gate, Porta Principalis Sinistra, the sill stones are in perfect preservation, with two grooves, which appear to have been worn by the wheels of carriages. When this gateway was opened out, a rough wall presented itself, which from the inferiority of its masonry, had evidently been the work of ruder hands than those employed upon the wall of the station, making it evident that the gateway had been built up long after the Roman occupation, and suggesting the idea that the camp may have been appropriated as a stronghold in the subsequent days of border warfare. This wall has been removed, and the gate, the opening of which between the pillars is eleven feet two inches, clearly exposed. The present height of the highest pillar is four feet eleven inches. To the south-east, at a distance of a hundred and thirty-six paces from the west gate, is the east gate—Porta Principalis Dextra. Between these gates would be the Via Principalis, which,” says Mr. Potter, “in some camps, is one hundred feet wide. The length from north to south of the camp at Burdoswald is about one-third greater than the breadth from east to west, which, according to Vegetius, who lived in the reign of the Emperor Valentinian, A.D. 385, was the most approved form.”

The eastern gateway is composed of much larger masonry than the west, although the opening between the pillars is less by thirteen inches. This gateway was likewise found to have been built up. A little distance to the south-east of this gate, the Roman road is clearly discernible. Midway, in the south rampart, is the south, or Decuman gateway. Adjoining the gate is a guard-room, ten feet four inches in length, eight feet broad, and standing at a height of eight feet. This chamber is fitted with a rude oven. Near the guard-room are the remains of a kiln for drying grain, apparently of Roman construction. The floor is flagged, and measures four feet four inches by three feet eight inches. Near the gate lie a number of wedge-shaped stones, which no doubt have formed the arched tops of the gateways. A fourth gateway has been opened out about fifty-five yards north of the east gateway. It is in fine preservation, having guard-rooms on either side, that on the left of entrance measuring ten feet seven inches by ten feet, and that on the right nine feet by ten. The openings of the double gateway measure each ten feet. The north pier of this gateway remains complete, including the impost and first stone of the arch, and presents the most perfect specimen of masonry along the whole length of the wall. The two first courses of stones measure one foot four inches square, the masonry being finely jointed, and the impost strikingly bold and massive. This pier is eight feet and a half in height. Within the gateway lie massive semicircular door-heads, which have belonged to the entrances to the guard-houses. About fifty feet of the wall of the station have been laid open to the north, and twelve courses of fine masonry, in perfect preservation, exposed. This gate had communicated with the suburbs, the lines of which are apparent in the undulations of the soil. From the discovery of floors in the area of the station, at a height of four feet above the Roman level, it is presumed that this camp had been occupied after the departure of the Romans, probably at a time when the gateways were built up for further security. The commanding situation of Burdoswald would make it a desirable point of vantage to some Saxon or Danish chieftain. A little to the north-east of Burdoswald, near a tumulus, some masonry was a while since removed to supply materials for a modern erection. This was called Haro’s or Harold’s Castle.

Within the area of the station, a room measuring ten feet by nine feet six inches, has been uncovered; the walls appear to have been coated with a red stucco. It was found to communicate with another of ten feet by nine feet six inches, in which is a hypocaust, and behind the hypocaust there is another chamber, measuring nine feet eight inches by nine feet six inches. These apartments, it is supposed, have been used as baths. While excavating one of these apartments a small headless statue seated in a raised chair was found, measuring thirty-four inches. The missing head is, I believe, in the museum at Newcastle. It were well if head and trunk could be reunited.