Oregon Historical Quarterly/Volume 27/Wishram

WISHRAM

By Henry J. Biddle

The purpose of this article is to show the true location of that ancient Indian village, commonly referred to as Wishram, which was situated somewhere on that broken stretch of the Columbia River beginning at the Falls of Celilo and ending at the rapids a few miles above the city of The Dalles. This broken stretch of river consists of a series of falls and rapids, not continuous, but alternating with stretches of gentle current; and to each of these rapids names were given by the early explorers, and by those that followed them. The question is to ascertain, by a study of the old writers, and by a study of the topography of the region involved, on which side of the river, and on which particular rapid, Wishram was located. The writer has made this study, and, while he does not pretend to have exhausted every available source of information, he does not think that sufficient additional evidence will be discovered to change the conclusions, as hereafter expressed.

To understand the question, it is first necessary to know something of the locality. The first white men to visit it were those keen observers, and accurate map makers, Lewis and Clark; and a study of their map of the region will give as good an idea of its character as the description of any later writer. It is unfortunate that most of the editions of the Lewis and Clark narrative do not contain the maps made by the explorers. But the Thwaites edition has facsimile copies of them. While it would be difficult to print one with this article, yet an idea of the map can be given by reproducing the lettering in the position it occupies on the copy of the original. Imagine then the top of the map to be East, the bottom West, the river shown in the center, and the lettering on each side of the river as below.

| Left side of Lewis and Clark Map. | Right side of Lewis and Clark Map. |

|---|---|

| 26 Mat Lodges of Indians of the E. nee-sher Nation. | Great Falls of 37 feet 8 inches. |

| 4 Mat Lodges of E. nee-shers. | Little Narrows, ¼ long, 45 yds. wide. |

| E-che-lute Nation of 21 large wooden houses sunk 6 feet underground. |

Long narrows, 2 m. long, 50 to 200 yds. wide. |

The name of Great Falls, or The Falls, was used by most subsequent travelers; later it was sometimes termed Les Chutes; today it is Celilo Falls.

The Little Narrows were subsequently called, sometimes, the Short Narrows, sometimes Les Petites Dalles, or the Little Dalles; today they are known as Ten Mile Rapids.

The Long Narrows were later called The Dalles, sometimes the Great Dalles; today they are Five Mile Rapids.

The Dalles Celilo Canal, built at great expense by the U. S. government, passes around all these obstructions to the navigation of the river. The U. S. engineers in charge of this work, named Five and Ten Mile Rapids from their distance from the boat landing at the city of The Dalles.[1]

The map of the U. S. engineers has been used as the basis of the map opposite page 115, and reference to this map will no doubt help to an understanding of this article. The writer has inserted on this map the names of the stations on the North Bank Railway, and some other points on the north side of the river, which will be referred to later.

Many writers, both those of the past and the present, have given vivid descriptions of the falls and the rapids below them. It is not intended to quote these descriptions, but to confine this article solely to the mention of the Indian villages at these points.

It will be noticed that on the Lewis and Clark map, opposite the Great Falls and Little Narrows, villages of mat lodges of the Eneeshers are shown. At the head of the Long Narrows the name of a different tribe appears, the Echelutes, and they live in wooden houses sunk partly underground. The following description of this village is quoted from the copy of the original journals of Lewis and Clark (Thwaites edition).

(Clark, Oct. 24, 1805, first draft.)

"...a village of 20 wood houses in a Deep bend to the Star'd Side below which a rugid black rock about 20 feet hiter than the Common high flud of the river...The natives of this village—one of whom envited me into his house which I found to be large and commodious, and the first wooden houses in which Indians have lived Since we left those in the vicinity of the Illinois, they are scattered permiscuisly on an elivated Situation near a mound of about 30 feet above the Common Leavel, which mound has Some remains of houses and has every appearance of being artificial."

The deep bend on the right side of the river, just above the Long Narrows (or Five Mile Rapids), as well as the mound mentioned by Lewis and Clark, are clearly shown on the map opposite page 115. The mound is plainly evident today, and has been marked by the writer on the map as closely to its true position as the scale of the map will permit A photograph of this mound is

On their return journey in 1806 the explorers endeavored to buy horses at this village. Lewis (April 16) speaks of it as the "Skillute village above the long narrows.....," and Clark says, this village is moved about 300 yards below the spot it stood last fall at the time we passed down, they were all above ground ......." This would put the Echelute village of 1806 exactly on the site of the present day Spedis.

It is greatly to be regretted that many of those who followed Lewis and Clark did not have the ability as map makers, or the accuracy in description, of those two great men. But the next white man to pass down that stretch of the river was an able cartographer, David Thompson. Unfortunately his notes, which have been published by Mr. Elliott,[2] are mostly made up of courses and distances, with but little descriptive matter. To understand them it is almost necessary to plat them out, and to compare the map thus obtained with a map of the present day. This the writer has done and the result shows that his camp of July 11, 1811, was two miles below where the river turns southwesterly, and where he began his portage. This puts it without question at the head of the Long Narrows. He says, "....camped with about 300 families....saw nothing of the bad Indians." No mention of the name of the tribe, or even of which bank of the river he camped on. But there are various sons for believing that he was on the right bank, at the village of the Echelutes. He probably changed his opinion of "bad Indians" after his return trip.

A great deal has been written about the troubles the travelers had with the Indians at these portages. To include this would greatly increase the length of this article, and be foreign to its purpose. Suffice it to say that they took advantage of their position to exact tribute from travelers, just as white men in similar positions do today. They soon found, as white men have found, that to exact an extortionate price for their services paid better than threats and robbery. Their descendants today are "good citizens," and own many automobiles. But the writer has never tried to rent an automobile from one of them. Perhaps in that case, they would still show themselves equal to whites.

The next white traveler to pass this point was Alexander Ross. In "Adventures of the first settlers on the Columbia River," is found:

(Aug. 4, 1811.)

"The main camp of the Indians is situated at the head of the narrows, and may contain, during the salmon season, 3000 souls, or more; but the constant inhabitants of the place do not exceed 100 persons, and are called Wy-am-pams; the rest are all foreigners from different tribes....... The long narrows, therefore, is the great emporium or mart of the Columbia,...."

It might be possible to assume that Wy-am-pams was simply a mis-spelling of Wishram, and the writer is almost inclined to this belief.

The next white visitor was Mr. Hunt, of the Astor expedition. It is necessary here to quote from Washington Irving's Astoria, published 1836. "On the 31st of January (1812), Mr. Hunt arrived at the falls of the Columbia, and encamped at the village of the Wish-ram, situated at the head of that dangerous pass in the river called 'the Long Narrows'.....Their habitations.....were superior to any the travelers had yet seen west of the Rocky Mountains. In general, the dwellings of the savages of the Pacific side of that great barrier were mere tents and cabins of mats, or skins, or straw.. . In Wish-ram, on the contrary, the houses were built of wood, with long sloping roofs."

It is evident that Irving was perfectly familiar with the narrative of Lewis and Clark, and meant exactly what he said when he put the first village of "houses built of wood" at the head of "the Long Narrows." But where did he get the name Wish-ram? It does not appear in the early narratives. Perhaps he got it in personal conversation with some of the voyageurs, perhaps in some journal which has never been published. The writer hopes that some day this question will be solved. But the description of wooden houses, and the location at the head of the Long Narrows, make it evident to the writer that the village of the Wish-ram was the village of the Echelute of Lewis and Clark. Attention must here be called to the fact that he does not call it Wishram, but the village of the Wishram. This is an important point in trying to explain the subsequent complexity of names. The next quotation is from Ross Cox, "Adventures on the Columbia River" (published 1831).

(July 12, 1812.) "We encamped late at the upper end of the falls, near a village of the Eneeshurs,... This confirms Lewis and Clark in placing the Eneeshers at the Falls, but nowhere in his narrative does he mention the Echelutes. It is possible that at this time the portage was sometimes made on the Oregon side of the river, where in later years a wagon road was built, and the villages on the Washington side thus passed unnoticed

In the narrative of Gabriel Franchere:

(April, 1814). "On the 12th, we arrived at a rapid called the Dalles;....." This is the first time the writer has found the term Dalles used for Long Narrows

Now comes a series of travelers, men of the highest intelligence, from whom accurate descriptions of this locality could be expected: David Douglas, Townsend, Nuttall, Wyeth; but they have little or nothing to say that is pertinent to this question.

David Douglas. Journal:

(June 20, 1825.) "Six miles below the Falls the water rushes through several narrow channels,.... It is called by the voyageurs The Dalles."

(Aug. 27, 1826.) "On the Dalles were at least from five hundred to seven hundred persons."

This merely confirms the fact that there was still a large Indian population at this point, but no mention is made of the names of tribes, or villages

Nathaniel J. Wyeth. Journal

(Oct. 24, 1832.) "We are now camped at the Great Dalles......The Indians are thieves but not dangerous......."

The next writer to mention this locality is Farnham, 1839. But as his evidence concerns the linguistic distinctions of the Indians, the writer will pass him by until he discusses that question from the beginning

Sir George Simpson, "An Overland Journey Around the World." (1841, near end of June.) "In the afternoon we reached Les Chutes, where we made a portage ..... As my experience, as well as that of others, had taught me to keep a strict eye on the 'Chivalry of Wishram' always congregated here in considerable numbers, I marshaled our party into three well armed bands,....."

"My own difficulties with these people occurred in 1829 on my upward voyage,...." (He then tells of a threatened attack at Les Chutes.)

"We were hardly ashore (1841), when we were surrounded by about a hundred and fifty savages of several tribes, who were all, however, under the control of one chief; and on this occasion the 'Chivalry of Wishram'

The writer has quoted rather fully from Simpson's work, because it might be interpreted as placing the Wishram at the Falls. The expression "Chivalry of Wishram" occurs just twice, and both times in quotation marks. Simpson undoubtedly borrowed this expression from Washington Irving, who used it a number of times in his Astoria. This work was published in 1836, five years before Simpson's journey, and he, no doubt, was familiar with it. The poetic sound of "Chivalry of Wishram" seems to have appealed to him, and the writer cannot help thinking that his use of it here was a case of "poetic license." But he says the savages were of several tribes, so not more than a portion of them could have been Wishram, and he makes no mention of their village In view of the positive statement of Irving, placing Wish ram at the head of the Long Narrows, the writer cannot think that this is negative evidence of any value.

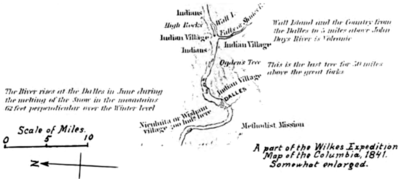

The next evidence comes from the report of the U. S. Exploring Expedition (Wilkes). That expedition sent a detachment up the Columbia, and made an excellent, although small-scale map of its course. This map is dated 1841, and is the first map showing any details of the river since that of Lewis and Clark. The writer being an engineer, and not by any means a historian, cannot help viewing the evidence of a map as far superior to any written narrative. In a written description, particularly one written long after the scenes were visited, errors are very apt to creep in. In a map, from a survey on the ground, this is very unlikely. (Of course one must except the classic incident of a fly-speck on the map of the Pacific Ocean being taken for an island). For this reason a somewhat enlarged photographic copy of this map is inserted opposite page 121. The text of the report gives (volume IV, page 388): "There are a number of villages in this neighborhood, and among them Wisham, mentioned in Irving's Astoria. This is situated on the left bank of the river and its proper name is Niculuita; Wisham being the name of the old chief, long since dead. There are now in the village about forty good lodges, built of split boards, with a roof of cedar bark, as before described. The Indians that live here seem much superior to those of the other villages; they number four hundred regular inhabitants....."

The map shows Niculuita or Wisham on the right, or Washington, side of the river, just above the word DALLES, and plainly at the head of the Long Narrows, as is evident from a comparison with the modern map shown opposite page 115. It is also evident that the word DALLES refers to the rapids. The subsequent city of The Dalles was located where the words Methodist Mission are placed. The placing of Wisham, in the text, on the left bank was probably due to the fact that the description was written while the party ascended the river, and they meant their left. It is also interesting to note that an Indian village is shown on the map just above the word DALLES, and on the Oregon side of the river. To this reference will be made later. An Indian village is also shown on each side of the river, about where the Falls would be.

In 1843 the emigrants brought their wagons down the river to the Dalles on the Oregon side.[3] The road thus formed became a portage route circumventing the Falls and all the rapids. It is therefore not to be supposed that later travelers would be apt to mention the Indians at the Narrows.

Paul Kane, "Wanderings of an Artist:"

(July 8, 1847.) "The Indians who reside and congregate about the Chutes for the purpose of fishing, are called the Skeen tribe;....."

Before summing up the evidence thus far obtained, the writer will go back to the earliest writers, and quote what they have to say about the nationality, and language, of these Indians at the Falls and Narrows.

While Lewis and Clark were resting at Rock Fort, alongside the present city of The Dalles, they were visited by the chiefs of the tribes on the river.

(Clark, Oct. 27, 1805)::

".......We took a Vocabulary of the Languages of those two chiefs which are very different notwithstanding they are situated within six miles of each other. Those at the great falls call themselves E-nee-shur and are understood on the river above: Those at the Great Narrows call themselves E-che-lute and is understood below."

Thus early was attention called to the fact that between the Great Falls and the Great Narrows was the boundary between what Lewis and Clark would have called two Nations, or what would commonly be called two tribes, of Indians. This might already have been surmised from the fact that the Indians at the Falls lived in mat lodges, those at the Long Narrows in wooden houses.

Excellent testimony to this effect is given in Farnham's Travels (1839). "At the Dalles is the upper village of the Chinooks. At the Shutes, five miles above, is the lower village of the Wallawallas. One of the missionaries, Mr. Lee, learns the Chinook language, and the other, Mr. Perkins, the Wallawalla; ......."

The writer is well aware that up to this point the evidence has been very confusing. How can the village of the Echelutes, of Lewis and Clark, be connected with the village of the Wishram, of Irving? The village of Wisham of Wilkes is evidently the same as Wishram; but how can Niculuita be explained? And yet all these names were applied to a village located on the Washington side of the river, at the head of the Long Narrows. Fortunately, what might be called linguistic evidence, some of which the writer has already cited, will help to solve the problem.

Edward Sapir[4] has collected the myths of the Wishram Indians, and compiled them in a book called "Wishram Texts."[5] This eminent authority on Indian languages explains much that has heretofore been obsucre He collected his information from Wishram Indians living on the Yakima Reservation, to which many of them had moved. In the introduction to his work, speaking of these Indians of the Yakima Reservation, he says:

"The greater part.....are speakers of Sahaptin dialects, the minority (Wishram, more properly Wi'cxam Indians, their own name for themselves is Ila'xluit) speak that dialect of Upper Chinookan-they occupied the northern bank of the Columbia about the Dalles."

P. 36. footnote. "At!at!a's furnace...was located on a small island.....near the Falls and only a short distance up from the main village of Wishram or Nixluidix. It was reckoned as the extreme eastern point on the river of the Wishram (hence also Chinookan) country."

(The map of the U. S. engineers, opposite page shows no island more than about one and a half miles above the head of the Long Narrows, or closer than about the same distance to the foot of the Little Narrows.) P. 38. footnote. "Nixlu'idix, across and up about five miles from the present town of The Dalles, was the chief village of the Wishram........itcxlu'it ('I am a Wishram') is probably the 'Echeloot' of Lewis and Clarke."

The question now begins to clarify itself. Without reference to the sites of these villages, it becomes clear that Nixlu'idix, the Niculuita of Wilkes, was the village of the E-che-lute Nation of Lewis and Clark. It also comes evident that Wishram was not the name of a village, but the name of a tribe. Indeed Irving says "the village of the Wish-ram." How the name Wishram orig inated is not yet clear. Sapir says these Indians called themselves Ila'xliut, but Wishram was evidently the name the whites applied to them; perhaps Wilkes' statement that Wisham was "the name of the old chief long since dead" may explain it. In any event the site of the ancient village called Wishram seems to be definitely located at the head of the Long Narrows, on the Washington side of the river, and adjacent to an artificial mound. This is the site of the present Indian village of Spedis, and there does not seem to be any doubt whatever that Spedis is Wishram.

None of the writers that have been quoted locate the village of Wishram at either the Little Narrows or the Falls, although Simpson intimates he met some of the tribe there. Indeed, the testimony of Lewis and Clark, of Farnham and Sapir, shows that the Indians above the Long Narrows belonged to a totally different tribe, and spoke a different language. The Wishrams spoke a Chinookan dialect, those above a Sahaptin dialect. To quote further from Wishram Texts:

P. 240. "The Wasco Indians......formerly occupied the southern shores of Columbia River in the region of The Dalles, and formed, with the closely related Wishram (more properly Wi'cxam) or Ila'xliut on the northern shore of the river, the most easterly members of the Chinookan stock."

P. 240, footnote. "Wasco......was the chief village of the Wascos. It was situated a few miles above The Dalles, opposite Nixlu'idix, the main village of the Wishrams."

In regard to the pronunciation of Wishram, or Wisham, which Sapir writes Wi'exam, something will now be said. Sapir explains the Indian sounds arbitrarily represented by letters of our alphabet: "c—like sh in English ship. x—like ch in German ach, but pronounced rather farther back."

So the pronunciation might be represented by Wish'-gham. But few people can produce the latter sound, even after prolonged practice. The writer, many years ago, spent some time in the New Mexican village of Zuñi, with a party of the U. S. Bureau of Ethnology. There was a similar sound in the Zuñi language, but very few of this party could produce it to the satisfaction of the Indians.

Mr. Glenn Ranck (President Vancouver Historical Society), formerly register of the U. S. Land Office in Vancouver, Washington, in an article published in the Oregonian, February 7, 1926, gives additional evidence on this point. He says that in the old treaties made with the Wisham tribes the name is always given as "Wisham." "However, some of the old tillicums, in pronouncing their tribal name, give it a sort of gutteral grunt, making it sound a little like "Wishgam." Mr. Ranck thinks "it might be well to adopt the name as it appears in the records of the United States government."

This is undoubtedly a good argument in favor of "Wisham." But in the writer's opinion, inasmuch as no ordinary white man can pronounce the name as the In dians do it, and as Wishram is about as close to their pronunciation as Wisham, it might be well to accept the more euphonious name, which has received the widest distribution, and been made classic, through the work of Washington Irving.

Concerning the later history of Wishram but little has been written. A treaty was concluded between the United States and the "Yakama," "Klickatat," and other tribes including the "Wish-ham," June 9, 1855. By this treaty the Indians gave up all their lands on the north bank of the Columbia, and accepted what is now the Yakima Reservation. And: "is further secured to said confederated tribes and bands of Indians, as also the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed places, in common with the citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary buildings for curing them." Many of the Wishram Indians moved to the Yakima Reservation, but still returned to exercise their fishing rights during the season. Some remained at their old village site, and some took up land allotments immediately around it. To protect their village, the government withdrew from entry a quarter section of land at its site.

To give some modern testimony as to the location of Wishram, the writer will quote from a letter, just received from Mr. J. T. Rorick. Mr. Rorick was an old settler in the Spedis region, and is now living at the city of The Dalles. He writes:

"I first saw Spedis in 1892. It was then known as Tum-water, but the Indians in referring to it legendary or historically used the name Wisram. My information is based on conversations with Bill Colwash, who claimed to be a lineal descendant of a long line of chiefs—chiefs from a time 'the memory of man runneth not to the contrary,' and Wishram has been their abiding place."

"The name Spedis was given to it when the S. P. & S. Rwy. had completed their line and established a sidetrack there, about 1906, and was in honor of Bill Spedis, a very old and likeable Indian patriarch."

"Mr. A. H. Curtiss, deceased, who located on that side in 1852, if I remember correctly, gave me the impression that he had gathered from the Indians as I had, that it had been an established point where the Colwashes and their tribe had resided from time immemorial, and being one of the best localities on the Columbia for spearing and dip-netting salmon, neighboring tribes, even from remote distances, would come annually for the June and September runs....."

"When I first came to that section, in 1892, there were probably 150 inhabitants of the village, also possibly 100 at Upper Tum-Water at Celilo Falls. At Wisram death and removal to the reservation allotments have left only three or four families—less than 20 persons."

(The writer thinks this estimate of the population too low. On the 2nd of January of this year, nine persons were counted in one small shack where one would hardly expect half that number.)

Mr. Ranck, in a letter to the writer, of Feb. 8, 1926, says:

"During my term as register of the Vancouver Land Office, from 1912 to 1916, Indians of the Wishram tribe frequently visited the Land Office at Vancouver, and told me a great deal concerning the old Wisham trading-mart. Chief Speedus, hereditary chief of the Wisham Indians, 'Wisham Sam,' and other Wisham Indians, told me that the ancient Wisham trading-town was situated adjoining the little railroad station known as 'Spedis.' In 1921, upon the invitation of Chief Speedus, I visited this old Indian village, and was shown around the town by the Chief, and other Indians. They al joined in assuring me that this was the ancient and historic trading-town of the Wisham tribe. In this they were corroborated by the mother and grandmother of Chief Speedus—the latter being Princess Shaw-naw'-way, the aged queen of the tribe. There is no doubt in my mind that this litle Indian village near the Spedis station is all that remains of the historic Wisham trading-mart."

In order not to lengthen this article, the writer has refrained from quoting the early writers except in regard to the location of Wishram. An exception has only been made in giving mentions of population, in order to show that this was always a point of importance among the Indians. Much has been written about the trading and gambling that took place there in the early days. But mention must be made of the fact that this was one of the best fishing points on the river, and for that reason its inhabitants clung to it.

The mound still stands beside the village, as when Lewis and Clark saw it. During the summers of 1924 and 1925, W. D. Strong and W. Egbert Schenck, students of anthropology at the University of California, made a careful investigation of this mound. The writer assisted in this work. Trenches were sunk to the bottom, and from the bedrock, at about thirteen feet depth, to the surface, the mound was found to be composed largely of charcoal, ashes, fish and animal bones, rocks broken by fire, and implements of stone and bone. In short, the mound from the bottom represents the accumulations, perhaps of thousands of years, of a camp site. Lewis and Clark showed their remarkable powers of observation when they said this mound had "every appearance of being artificial." The knowledge of pre-historic Wishram gained from this work will be published in due time.

Another feature of interest in this neighborhood is the abundance of pictures incised in the faces of the cliffs, (Petroglyphs), or painted on them, (Pictographs). The former are most abundant. A high water channel of the river, about three-quarters of a mile above Spedis, has so many of these Petroglyphs that Mr. Strong christened it Petroglyph Canyon. Its location is shown on the map opposite page 115. The largest of these pictures is a face, about six feet in diameter, on a smooth pillar of the cliff immediately above Spedis. It is incised in the rock, and hence a Petroglyph, but it also shows traces of former coloring. The Indians call it Tsa-gig-la'-lal, and give a meaning of this name something like this, "She who watches you as you go by." Photographs of this face, and of two typical Petroglyphs in this neighborhood, are shown on the upper portion of the illustration opposite page 129.

To sum up the evidence set forth in this article, it seems to be proven that the village of the Echelutes, Wishram, Wisham, Niculuita and Spedis, were all one and the same village, and that this village was located on the Washington shore of the Columbia, at the head of the Long Narrows, or Five Mile Rapids. It also appears to be proven that this village was the most easterly settlement of the Chinookan tribes, and that above them began the Sahaptin tribes, extending far to the eastward. Under these circumstances, it would seem to the writer a gross historical error to apply the name of Wishram to any other point than Spedis, particularly to any point higher up the river, where another nation lived.

This Indian village has existed practically on its present site since the day of Lewis and Clark, and, the evidence of the mound shows, for perhaps some thousands of years before that day. It exists today, as it did in the past, because there is good fishing there. The Spedis Indians catch the salmon with dip-nets today precisely as their ancestors did in the remote past, and will continue to catch them there as long as a man of the tribe is left alive.

Notes

edit- ↑ T. C. Elliott. The Dalles-Celilo Portage. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 1915. This article contains excellent illustrations of the falls and rapids, and a great amount of interesting historical information.

- ↑ T. C. Elliott. Journal of David Thompson. Oregon Historical Quarterly, March, June, 1914.

- ↑ T. C. Elliott, The Dalles-Celilo Portage, Ore. Hist. Quar., 1915.

- ↑ Dr. Edward Sapir, Chief of Division of Anthropology, Geological Survey of Canada. A. B. Columbia, 1904; A. M. 1905; Ph. D. 1909.

- ↑ Wishram Texts, Publications of the American Ethnological Society, volume II, 1909.

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1929.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1928, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 95 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse