Any air which has the natural as well as the altered note may be set down as either modern, or as having been tampered with in modern times. The major seventh in a minor key is also a sure sign of modern writing or modern meddling, though it cannot be denied that the natural note, the minor seventh, sounds somewhat barbarous to the unaccustomed ear—and yet grand effects are produced by means of it. In a tune written otherwise in the old tonality, the occurrence of the major seventh sounds weak and effeminate when compared with the robust grandeur of the full tone below.

A few more examples may be given to show the mingling of the pentatonic with the completed scale. 'Adieu Dundee'—also found in the Skene MS.—is an example of a tune written as if in the natural key, and yet really in a modified G minor.

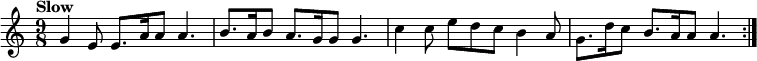

Adew Dundee.

Of course in harmonising the tune it would be necessary to write it in two flats; but in the melody the B is entirely avoided and the E♮ in the 15th bar is used to modulate into D minor, thus skilfully making a note available which belonged to the scale of the instrument though not to that of the tune. Another example is 'The wauking of the fauld,' which, played in the same key (G minor), has the same peculiarity in the 13th bar; this however is the case only in modern versions of the air, for that given by Allan Ramsay in the 'Gentle Shepherd' (1736) is without the E.

The closes of Scotish tunes are often so singular that a notice of their peculiarities ought not to be omitted. The explanation of the fact that almost every note of the scale is found in use as a close, is really not difficult, if the circumstances are taken into consideration. In the olden time, many of the tunes were sung continuously to almost interminable ballads, a full close at the end of every quatrain was therefore not wanted. While the story was incomplete the old minstrel no doubt felt that the music should in like manner show that there was more to follow, and intentionally finished his stanza with a phrase not to be regarded as a close, but rather as a preparation for beginning the following one; though when he really reached the end he may possibly have concluded with the key-note.

The little tune 'Were na my heart licht' [p. 444b] is an excellent example of what has just been said. It consists of four rhythms of two bars each; a modern would have changed the places of the third and fourth rhythms, and finished with the key-note, but the old singer intentionally avoids this, and ends with the second of the scale, a half close on the chord of the dominant.

Endings on the second or seventh of the scale are really only half closes on intervals of the dominant chord, the fifth of the key. Endings on the third and fifth again are half closes on intervals of the tonic chord or key-note, while those on the sixth are usually to be considered as on the relative minor; and occasionally the third may be treated as the fifth of the same chord. To finish in so unusual a manner has been called inexplicable, and unsatisfactory to the ear, whereas viewed as mere specimens of different forms of Da Capo these endings become quite intelligible, the object aimed at being a return to the beginning and not a real close.

Of the Gaelic Music.

If the difficulty of estimating the age of the music of the Lowlands is great, it is as nothing compared to what is met with in considering that of the Highlands.

When a Gael speaks of an ancient air he seems to measure its age not by centuries; he carries us back to pre-historic times for its composition. The Celts certainly had music even in the most remote ages, but as their airs had been handed down for so many generations solely by tradition, it may be doubted whether this music bore any striking resemblance to the airs collected between 1760 and 1780 by the Rev. Patrick McDonald and his brother. That he was well fitted for the task he had set himself is borne out by the following extract from a letter addressed to the present writer in 1849 by that excellent water-colourist Kenneth Macleay, R.S.A. He says, 'My grandfather, Patrick Macdonald, minister of Kilmore and Kilbride in Argyllshire who died in 1824 in the 97th year of his age was a very admirable performer on the violin, often played at the concerts of the St. Cecilia Society in Edinburgh last century, and was the first who published a collection of Highland airs. These were not only collected but also arranged by himself.' In the introduction to the work there are many excellent observations regarding the style and age of the tunes. The specimens given of the most ancient music are interesting only in so far as they show the kind of recitative to which ancient poems were chanted, for they have little claim to notice as melodies. The example here given is said to be 'Ossian's soliloquy on the death of all his contemporary heroes.'

There are however many beautiful airs in the collection; they are simple, wild, and irregular; but before their beauty can be perceived they must be sung or hummed over again and again. Of the style of performance the editor says: