clinging to the ore. It obtained complete but restricted symmetry with the composers immediately preceding Beethoven, but arrived only at last with him at that expansion which made it at once perfect and intelligible, and yet boundless in range within the limits of the art-material at the composer's command.

Prior to Beethoven, the development of a long work was based upon antitheses of distinct tunes and concrete lumps of subject representing separate organisms, either merely in juxtaposition, or loosely connected by more or less empty passages. There were ideas indeed, but ideas limited and confined by the supposed necessities of the structure of which they formed a part. But what Beethoven seems to have aimed at was the expansion of the term 'idea' from the isolated subject to the complete whole; so that instead of the subjects being separate, though compatible items, the whole movement, or even the whole work, should be the complete and uniform organism which represented in its entirety a new meaning of the word 'idea,' of which the subjects, in their close connection and inseparable affinities, were subordinate limbs. This principle is traceable in works before his time, but not on the scale to which he carried it, nor with his conclusive force. In fact, the condition of art had not been sufficiently mature to admit the terms of his procedure, and it was barely mature enough till he made it so.

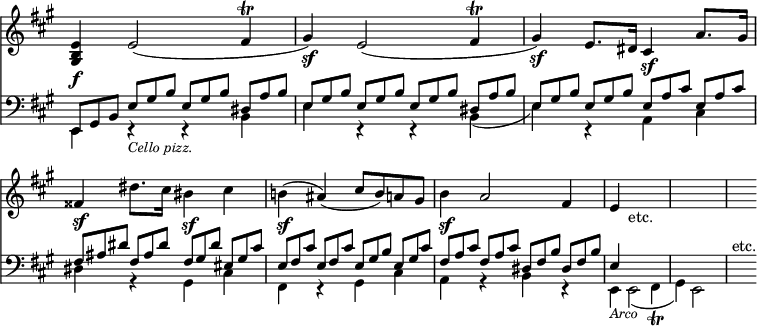

His early works were in conformity with the style and structural principles of his predecessors; but he began, at least in pianoforte works, to build at once upon the topmost stone of their edifice. His earliest sonatas (op. 2) are on the scale of their symphonies. He began with the four-movement plan which they had almost entirely reserved for the orchestra. In the second sonata he already produces an example of his own peculiar kind of slow movement, full, rich, decisive in form, unaffected in idea, and completely divested of the elaborate graces which had been before its most conspicuous feature. In the same sonata also he produces a scherzo, short in this instance, and following the lines of the minuet, but of the genuine characteristic quality. Soon, in obedience to the spread of his idea, the capacity of the instrument seems to expand, and to attain an altogether new richness of sound, and a fullness it never showed before, as in many parts of the 4th Sonata (op. 7), especially the Largo, which shows the unmistakeable qualities which ultimately expanded into the unsurpassed slow movement of the Opus 106. As early as the 2nd Sonata he puts a new aspect upon the limits of the first sections; he not only makes his second subject in the first movement modulate, but he develops the cadence-figure into a very noticeable subject. It is fortunately unnecessary to follow in detail the various ways in which he expanded the structural elements of the sonata, as it has already been described in the article Beethoven, and other details are given in the article Form. In respect of the subject and its treatment, a fortunate opportunity is offered by a coincidence between a subordinate subject in a sonata of Haydn's in C, and a similar accessory in Beethoven's Sonata for cello and pianoforte in A major (op. 69), which serves to illustrate pregnantly the difference of scope which characterises their respective treatment. Haydn's is as follows:—

and Beethoven's:—