A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

��nown you; If now I b dis-dain'd. I wish my cres. pp

heart had ne-ver known you.

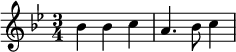

The method is, it will be seen, identical in principle with the old system known by the name of the 'Moveable Do,' and the notation is only so far new in that symbols are written down which have been used, orally, for some eight centuries. The syllables attributed to Guido, circa 1024 [see Hexachord], were a notation, not of absolute pitch, but of tonic relation; his ut, re, mi, etc., meaning sometimes

sometimes

and so on, according as the tonic changed its pitch; and this ancient use of the syllables to represent, not fixed sounds, but the sounds of the scale, has been always of the greatest service in helping the singer, by association of name with melodic effect, to imagine the sound. The modern innovation of a 'fixed Do' is one of the many symptoms (and effects) of the domination of instruments over voices in the world of modern music.[1] The Tonic Sol-fa method, indeed, though spoken of as a novelty, is really a reversion to ancient practice, to a principle many centuries old. Its novelty of aspect, which is undeniable, results from its making this principle more prominent, by giving it visual, as well as oral, expression; that is, by using the old soundnames as written symbols. Those who follow the old Italian and old English practice of the 'Moveable Do' are, in effect, Tonic Sol-faists. The question of notation is a distinct one, and turns on considerations of practical convenience. The argument for adhering to the old tonic use of the syllables rests broadly on the ground that the same thing should be called by the same name; that, for example, if

is to be called do, do, re | si, do, re, it is not reasonable that

the essential effect of which on the ear is the same—for the tune is the same, and the tune is all that the ear feels and remembers—should be called by another set of names, si, si, do | la, si, do. And, conversely, it is not reasonable that if, for example, in the passage

the last two sounds are called do, la,—the same sounds should be also called do, la, in the passage

where they sound wholly different; the identity of pitch being as nothing compared to the change of melodic effect—a change, in this case, from the plaintive to the joyous. It is on this perception of the 'mental effect' of the sounds of the scale that the Tonic Sol-fa teacher relies as the means of making the learner remember and reproduce the sounds. And it is this that constitutes the novelty of the system as an instrument of teaching.

- ↑ Sir John Herschel said in 1868 (Quarterly Journal of Science, art. 'Musical Scales')—'I adhere throughout to the good old system of representing by Do, Re, Mi, Fa, etc., the scale of natural notes in any key whatever, taking Do for the key-note, whatever that may be, in opposition to the practice lately introduced (and soon I hope to be exploded) of taking Do to represent one fixed tone C,—the greatest retrograde step, in my opinion, ever taken in teaching music, or any other branch of knowledge.'