The FHWA Federal Women’s Program was established in 1971. In the early part of 1974, the Spanish-Speaking Program was established to deal with the employment concerns and problems of Hispanics employed by the FHWA.

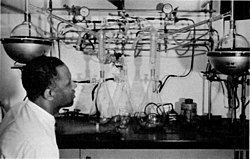

To study the behavior of asphalt in service, an FHWA analyst is using a vacuum distillation technique to remove the bulk of the solvent from solutions of asphalts extracted from pavements.

Meanwhile two major changes in the EEO civil rights program took place. First, the 1970 Federal-Aid Highway Act gave the agency authority to add on-the-job training aimed at furthering equal employment opportunity. Goals were set for specified numbers of persons to receive training on selected construction projects, and supportive services for on-the-job training were provided the following year. Second, the Department of Transportation published rules and regulations in 1970 to implement Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, or national origin in federally assisted programs.

Because of FHWA’s highly decentralized organizational approach, most of FHWA’s EEO responsibilities are carried out at the field level. The Headquarters develops overall policy and monitors the results through review of reports of Title VI and Title VIII (Fair Housing) activities, contract compliance, special programs (minority business enterprise, summer youth opportunity program, on-the-job training, and supportive services), and the internal employment practices of FHWA offices. The FHWA Headquarters and field EEO staffs also make onsite Federal-aid project reviews and onsite reviews of State highway agencies.

In FHWA’s direct construction program, directives were issued specifying that a clause be included in all contracts requiring contractors to take affirmative action to recruit and employ the disadvantaged, including minorities and women, and to achieve positive equal employment opportunity results on construction projects. These directives were followed by additional procedures for monitoring and evaluating the contractors’ compliance with EEO.

In June 1973, a directive to implement the Minority Business Enterprise Program was issued. This directive requires that, where feasible, direct Federal projects shall be set aside for contract negotiation and subsequent award to a minority-owned firm under the requirements of section 8(a) of the Small Business Act of 1958 (P.L. 85-536). The FHWA field and Headquarters offices have taken the initiative to implement this program to develop minority contractors with the capability to perform highway construction or perform highway research studies.

Since 1899 when the River and Harbor Act was passed requiring permits to build bridges over navigable waters, coordination, consultation or receipt of permits from other agencies has been required for highway projects as the result of various legislation. In 1958 the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act was passed, in 1966 the Historic Preservation Act, and in 1968 the Wild and Scenic River Act. Since then many new acts and requirements have emerged, such as:

Federal Water Pollution Control Amendment of 1972

Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972

Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries—1972

Endangered Species Act of 1973

Archeological and Historic Preservation Act of 1974

As their titles imply, these requirements protect navigable waterways, marine and animal wildlife, the physical environment, air and water pollution impacts, floodplains, etc. This is not a complete list, but it does indicate the extent of Federal safeguards against undesirable impacts. Compliance with these new legislative requirements is very time consuming and may take up to 18 months to accomplish. This is one of the reasons why it takes much longer now from conception of a highway project until it is completed and open to traffic. It should be pointed out that all of these specific coordination and permit requirements are in addition to the basic environmental impact evaluations required for all highway projects since 1970.

As may be presumed, the Federal-aid highway program has not been without its legal complications which ultimately have wound up in courts of law. For example, a legal issue arose out of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972. Section 404 of the Act provided that permits from the Army Corps of Engineers would be required for dredge and fill activities in navigable waters. A District Court order in March 1975 interpreted the term “navigable waters” as meaning all waters of the United States and thus subject to the Corps of Engineers jurisdiction in regard to the need for section 404 permits. Since almost all highway projects touch some body of water in the expanded sense, this could conceivably include a need for a permit for a highway crossing wetlands or even a stream. Congressional hearings have been held to alleviate this problem, but to date no satisfactory solution has emerged.

As a result of the enactment in 1969 of the National Environmental Policy Act and related provisions contained in the 1970 Highway Act, each proposed highway project must be evaluated to determine its impact on the environment, The States were first required to develop and use an approved process to assure that

223