tion offered to pay the expert’s salary and expenses, he agreed to participate and designated Special Agent Charles T. Harrison of New Jersey as the OPRI’s representative.[N 1]

The Association mounted a high-powered publicity campaign to prepare the way for the “Good Roads Train.” Advance agents organized local conventions and lined up donations of labor and materials for demonstration projects. The train, consisting of nine flat cars loaded with road machinery, and two sleeping cars for the operators, laborers, officials, road experts and press representatives, pulled out of Chicago early in April 1901, under the management and control of Colonel Richardson. Before returning in August, it stopped at 16 cities in five States, where the construction crew built sample roads of earth, stone or gravel varying in length from ½ mile to 1½ miles. Director Dodge, who went along on the first trip from Chicago to New Orleans, expressed his enthusiasm for the project in this glowing account:

About 20 miles of earth, stone, and gravel roads were built and 15 large and enthusiastic conventions were held. The numbers attending these conventions and witnessing the work were very large, in nearly every instance more than a thousand persons and in some cases 2,000 persons being present. Among the attendants were leading citizens and officials, including governors, mayors, Congressmen, members of legislatures, judges of the county court, and road officials. This was undoubtedly the most successful campaign ever waged for good roads, and the expedition has been of great service to the cause, and especially to the people of the Mississippi Valley.[1]

At this time the steam railroads were among the strongest supporters of good roads. Secure in their position as the backbone of the American transportation system, they were anxious to extend their tributary traffic areas and also to overcome some of the widespread hostility engendered by their high-handed methods of dealing with the public. The economic aspect of the railway interest in roads was aptly expressed by an official of the Southern Railroad in 1902:

. . . They [the Southern Railroad] now handle the products of from 2 to 5 miles on each side of their tracks. In the winter season they can not get the products that are any farther away. If you had improved roads, they would be able to serve the country 20 to 30 miles from their tracks. . . . If you are a shipper, you know that at some seasons of the year it is hard to get cars; that every railroad in the United States suffers from a lack of cars and locomotives, and that the industries of almost every community suffer on this account. This is because the traffic on all railroads is so greatly congested within a few months of the year. It is not divided over the twelve months as it ought to be. If there were good roads leading to every railroad station in the United States, the railroads would be able to get along with half the cars they now need. . . .[2]

The Illinois Central Railroad “expedition” was so successful that Colonel Moore had little difficulty lining up others. One left Chicago on the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad for Buffalo, where it was placed on exhibit on the grounds of the Pan-American Exposition during the International Good Roads Congress during September 1901.[3]

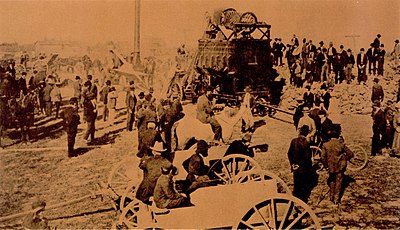

The crushing plant in operation at Winston-Salem, N.C., during a macadam roadbuilding demonstration in 1901.

- ↑ Charles T. Harrison replaced E. G. Harrison who died February 6, 1901.

49