TIMBER.

Growth of Timber Trees.

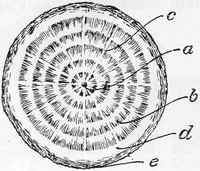

Structure of Tree Trunk.—Trees which produce timber are known botanically as exogens, or outward growers, because the new wood is added underneath the bark outside that already formed. The whole section (Fig. 124) consists of (a) pith in the centre, which dries up and disappears as the tree matures; (b) woody fibre or long

tapering bundles of vascular tissue forming the duramen or heartwood, arranged in rings, each of which is considered to represent a year's growth, and interspersed with (c) medullary rays or transverse septa consisting of flat, hard plates of cellular tissue known to carpenters as "silver-grain," or "felt," or "flower," and showing most strongly in oak and beech: the heartwood is comparatively dry and hard, from the compression produced by the newer layers; (d) alburnum, or sapwood, which is the immature woody fibre recently deposited. In coniferous trees the sapwood is only distinguishable by a slight greenish tinge when dry, but when wet it holds the moisture much longer than the heartwood, and can often be detected in that way; (e) the bark, which is a protecting coat on the outside of the tender sapwood; it receives additions on the inside during the autumn, which cause it to crack and become very irregular in old trees. The mode of growth is as follows: In the spring moisture from the earth is absorbed by the roots, and rises through the stem as sap to form the leaves. The leaves give off moisture and absorb carbon (in the form of carbonic acid gas), which thickens the sap. In the autumn the sap descends inside the bark and adds a new layer of wood to the tree. The actual growth is less regular than appears in Fig. 124, and more resembles Fig. 125.

Formation of Wood.—Fig. 125 further illustrates the manner in which the stem of a timber tree grows by the deposit of successive layers of wood on the outside under the bark, while at the same time the bark becomes thicker by the deposit of layers on its under side. Upon examining the cross section of an oak log as Fig. 125, it is found that the wood is made up of several concentric layers or rings, each ring consisting in general of two parts, the outer part being usually darker in colour, denser, and more solid than the inner part, the difference between the parts varying in different kinds of trees. These layers are called annual rings, because one of them is, as a rule, deposited every year in a manner which will be presently explained. In the centre of the first layer is a column of pith, from which planes, seen in section as thin lines (in many woods not discernible), radiate towards the bark, and in some cases similar lines from the bark converge towards the centre, but do not reach the pith (see Figs. 125 and 126). These radiating lines are known as medullary rays or transverse septa. When they are of large size and strongly marked, as in some kinds of oak,

26