and especially under the pontificate of Pope Damasus (366–384), basilicas and chapels were erected in Rome and elsewhere in honour of the most famous martyrs, and the altars, when at all possible, were located directly above their tombs.

Altar with fenestella in S. Alessandro, Rome V. Century The "Liber Pontificalis" attributes to Pope Felix I (269–274) a decree to the effect that Mass should be celebrated on the tombs of the martyrs (constituit supra memorias martyrum missas celebrare, "Lib. Pont.", ed. Duchesne, I, 158). However this may be, it is clear from the testimony of this authority that the custom alluded to was regarded at the beginning of the sixth century as very ancient (op. cit., loc. cit., note 2). For the fourth century we have abundant testimony, literary and monumental. The altars of the basilicas of St. Peter and St. Paul, erected by Constantine, were directly above the Apostles' tombs. Speaking of St. Hippolytus, the poet Prudentius refers to the altar above his tomb as follows:—

Talibus Hippolyei corpus mandatur opertis

Propter ubi apposita est ara dicata Deo.

Finally, the translation of the bodies of the martyrs Sts. Gervasius and Protasius by St. Ambrose to the Ambrosian basilica in Milan is an evidence that the practice of offering the Holy Sacrifice on the tombs of martyrs was long established. The great veneration in which the martyrs were held from the fourth century had considerable influence in effecting two changes of importance with regard to altars. The stone slab enclosing the martyr's grave suggested the stone altar, and the presence of the martyr's relics beneath the altar was responsible for the tomblike under-structure known as the confessio. The use of stone altars in the East in the fourth century is attested by St. Gregory of Nyssa (P. G., XLVI, 581) and St. John Chrysostom (Hom. in I Cor., xx); and in the West, from the sixth century, the sentiment in favour of their exclusive use is indicated by the Decree of the Council of Epaon alluded to above. Yet even in the West wooden altars existed as late as the reign of Charlemagne, as we infer from a capitulary of this emperor forbidding the celebration of Mass except on stone tables consecrated by the bishop [in mensis lapideis ab episcopis consecratis (P. L., XCVII, 124)]. From the ninth century, however, few traces of the use of wooden altars are found in the domain of Latin Christianity, but the Greek Church, up to the present time, permits the employment of wood, stone, or metal.

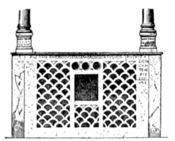

II. The Confessio.—Martyrs were Confessors of the Faith—Christians who "confessed" Christ before men at the cost of their lives—hence the name confessio was applied to their last resting-place, when, as happened frequently from the fourth century, an altar was erected over it. Up to the seventh century in Rome, as we learn from a letter of St. Gregory the Great to the Empress Constantia, a strong sentiment against disturbing the bodies of the martyrs prevailed. This fact accounts for the erection of the early Roman basilicas, no matter what the obstacles encountered, over the tombs of martyrs; the church was brought to the martyr, not the martyr to the church. The altar in such cases was placed above the tomb with which it was brought into the closest relation possible. In St. Peter's, for instance, where the body of the Apostle was interred at a considerable depth below the level of the floor of the basilica, a vertical shaft, similar to the luminaria in some of the catacombs, was constructed between the Altar and the sepulchre. Across this shaft, at some distance from each other, were two perforated plates, called cataractæ, on which cloths (brandea) were placed for a time, and afterwards highly treasured as relics. But the remains of St. Peter, and those of St. Paul, were never disturbed. The tombs of both Aposties were enclosed by Constantine in cubical cases, each adorned with a gold cross (Lib. Pont., ed. Duchesne, I, 176). From that date to the present time, except in 1594, when Pope Clement VIII with Bellarmine and some other cardinals saw the cross of Constantine on the tomb of St. Peter, the interior of their tombs has been hidden from view. Another form of confessio was that in which the slab enclosing the martyr's tomb was on a level with the floor of the sanctuary (presbyterium). As the sanctuary was elevated above the floor of the basilica the altar could thus be placed immediately above the tomb, while the people in the body of the church could approach the confessio and through a grating (fenestella confessionis) obtain a view of the relics. One of the best examples of this form of confessio is seen at Rome in the Church of San Giorgio in Velabro, where the ancient model is followed closely. A modified form of the latter (fifth-century) state of confessio is that in the basilica of San Alessandro on the Via Nomentana, about seven miles from Rome. In this case the sanctuary floor was not elevated above the floor of the Basilica, and therefore the fenestella occupied the space between the floor and the table of the altar, thus forming a combination tomb and table altar. In the fenestella of this altar there is a square opening through which brandea could be placed on the tomb.

III. The Ciborium.—From the fourth century altars were, in many instances, covered by a canopy supported on four columns, which not only formed a protection against possible accidents, but in a greater degree served as an architectural feature of importance. This canopy was known as the ciborium or tegurium. The idea of it may have been suggested by memoriæ such as those which from the earliest times protected the graves of St. Peter and St. Paul; when the basilicas of these Apostles were erected, and their tombs became altars, the appropriateness of protecting-structures over the tomb-altars, bearing a certain resemblance to those which already existed, would naturally suggest itself. However this may be, the dignified and beautifully ornamented ciborium as the central point of the basilica, where all religious functions were performed, was an artistic necessity. The altar of the basilica was simple in the extreme, and, consequently, in itself too small and insignificant to form a centre which would be in keeping with the remainder of the sacred edifice. The ciborium admirably met this requirement. The altars of the basilicas erected by Constantine at Rome were surmounted by ciboria, one of which, in the Lateran, was known as a fastigium and is described with some detail in the "Liber Pontificalis". The roof was of silver and weighed 2,025 pounds; the columns were probably of marble or of porphyry, like those of St. Peter's. On the front of the ciborium was a scene which about this time became a favourite subject with Christian artists: Christ enthroned in the midst of the Apostles. All the figures were five feet in height; the statue of Our Lord weighed 120 pounds, and those of the Apostles ninety pounds each. On the opposite side, facing the apse, Our Lord was again represented enthroned, but surrounded by four Angels with spears; a good idea of the appearance of the Angels may be had from a mosaic of the same subject in