well as an illustration (sounded an octave higher than the notation).

| French | Italian 4 course | Italian 6 course |

|

|

|

During the 18th century the cittern, citra or English guitar, had twelve wire strings in six pairs of unisons tuned thus:

The introduction of the Spanish guitar, which at once leapt

into favour, gradually displaced the English variety. The

Spanish guitar had gut strings twanged by the fingers. The

last development of the cittern before its disappearance was the

addition of keys. The keyed cithara[1] was first made by Claus

& Co. of London in 1783. The keys, six in number, were

placed on the left of the sound-board, and on being depressed

they acted on hammers inside the sound-chest, which rising

through the rose sound-hole struck the strings. Sometimes

the keys were placed in a little box right over the strings, the

hammers striking from above. M. J. B. Vuillaume of Paris

possessed an Italian cetera (not keyed) by Antoine Stradivarius,[2]

1700 (now in the Museum of the Conservatoire, Paris), with

twelve strings tuned in pairs of unisons to E, D, G, B, C, A,

which was exhibited in London in 1871.

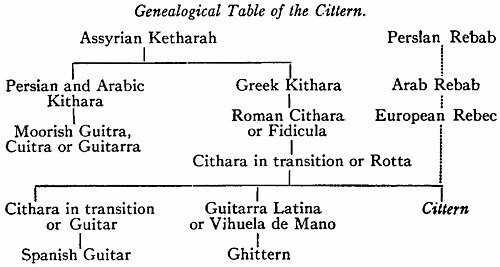

The cittern of the 16th century was the result of certain transitions which took place during the evolution of the violin from the Greek kithara (see Cithara).

The cittern has retained the following characteristics of the archetype. (1) The derivation of the name, which after the introduction of the bow was used to characterize various instruments whose strings were twanged by fingers or plectrum, such as the harp and the rotta (both known as cithara), the citola and the zither. In an interlinear Latin and Anglo-Saxon version of the Psalms, dated A.D. 700 (Brit. Mus., Vesp. A. 1), cithara is translated citran, from which it is not difficult to trace the English cithron, citteran, cittarn, of the 16th century. (2) The construction of the sound-chest with flat back and sound-board connected by ribs. The pear-shaped outline was possibly borrowed from the Eastern instruments, both bowed as the rebab and twanged as the lute, so common all over Europe during the middle ages, or more probably derived from the kithara of the Greeks of Asia Minor, which had the corners rounded. These early steps in the transition from the cithara may be seen in the miniatures of the Utrecht Psalter,[3] a unique and much-copied Carolingian MS. executed at Reims (9th century), the illustrations of which were undoubtedly adapted from an earlier psalter from the Christian East. The instruments which remained true to the prototype in outline as well as in construction and in the derivation of the name were the ghittern and the guitar, so often confused with the cittern. It is evident that the kinship of cittern and guitar was formerly recognized, for during the 18th century, as stated above, the cittern was known as the English guitar to distinguish it from the Spanish guitar. The grotesque head, popularly considered the characteristic feature of the cittern, was probably added in the 12th century at a time when this style of decoration was very noticeable in other musical instruments, such as the cornet or Zinck, the Platerspiel, the chaunter of the bagpipe, &c. The cittern of the middle ages was also to be found in oval shape. From the 13th century representations of the pear-shaped instrument abound in miniatures and carvings.[4]

A very clearly drawn cittern of the 14th century occurs in a MS. treatise on astronomy (Sloane MS. 3983, Brit. Mus.) translated from the Persian of Albumazar into Latin by Georgius Zothari Zopari Fenduli, priest and philosopher, with a prologue and numerous illustrations by his own hand; the cittern is here called giga in an inscription at the side of the drawing.

References to the cittern are plentiful in the literature of the 16th and 17th centuries. Robert Fludd[5] describes it thus: “Cistrona quae quatuor tantum chordas duplicatas habet easque cupreas et ferreas de quibus aliquid dicemus quo loco.” Others are given in the New English Dictionary, “Cittern,” and in Godefroy’s Dict. de l’anc. langue franç. du IX e au XV e siècle. (K. S.)

CITY (through Fr. cité, from Lat. civitas). In the United Kingdom, strictly speaking, “city” is an honorary title, officially applied to those towns which, in virtue of some pre-eminence (e.g. as episcopal sees, or great industrial centres), have by traditional usage or royal charter acquired the right to the designation. In the United Kingdom the official style of “city” does not necessarily involve the possession of municipal power greater than those of the ordinary boroughs, nor indeed the possession of a corporation at all (e.g. Ely). In the United States and the British colonies, on the other hand, the official application of the term “city” depends on the kind and extent of the municipal privileges possessed by the corporations, and charters are given raising towns to the rank of cities. Both in France and England the word is used to distinguish the older and central nucleus of some of the large towns, e.g. the Cité in Paris, and the “square mile” under the jurisdiction of the lord mayor which is the “City of London.”

In common usage, however, the word implies no more than a somewhat vague idea of size and dignity, and is loosely applied to any large centre of population. Thus while, technically, the City of London is quite small, London is yet properly described as the largest city in the world. In the United States this use of the word is still more loose, and any town, whether technically a city or not, is usually so designated, with little regard to its actual size or importance.

It is clear from the above that the word “city” is incapable of any very clear and inclusive definition, and the attempt to show that historically it possesses a meaning that clearly differentiates it from “town” or “borough” has led to some controversy. As the translation of the Greek πόλις or Latin civitas it involves the ancient conception of the state or “city-state,” i.e. of the state as not too large to prevent its government through the body of the citizens assembled in the agora, and is applied not to the place but to the whole body politic. From this conception both the word and its dignified connotation are without doubt historically derived. On the occupation of Gaul the Gallic states and tribes were called civitates by the Romans,

- ↑ See Carl Engel, Catalogue of the Exhibition of Ancient Musical Instruments (London, 1872), Nos. 280 and 290.

- ↑ See note above. Illustration in A. J. Hipkins, Musical Instruments; Historic, Rare and Unique (Edinburgh, 1888).

- ↑ For a résumé of the question of the origin of this famous psalter, and an inquiry into its bearing on the history of musical instruments with illustrations and facsimile reproductions, see Kathleen Schlesinger, The Instruments of the Orchestra, part ii. “The Precursors of the Violin Family,” pp. 127-166 (London, 1908–1909).

- ↑ An oval cittern and a ghittern, side by side, occur in the beautiful 13th-century Spanish MS. known as Cantigas de Santa Maria in the Escorial. For a fine facsimile in colours see marquis de Valmar, Real. Acad. Esq., publ. by L. Aguado (Madrid, 1889). Reproductions in black and white in Juan F. Riaño, Critical and Bibliog. Notes on Early Spanish Music (London, 1887). See also K. Schlesinger, op. cit. fig. 167, p. 223, also boat-shaped citterns, figs. 155 and 156, p. 197. Cittern with woman’s head, 15th century, on one of six bas-reliefs on the under parts of the seats of the choir of the Priory church, Great Malvern, reproduced in J. Carter’s Ancient Sculptures, &c., vol. ii. pl. following p. 12. Another without a head, ibid. pl. following p. 16, from a brass monumental plate in St Margaret’s, King’s Lynn.

- ↑ Historia utriusque Cosmi (Oppenheim, ed. 1617), i. 226.