no means so pleasant. Mersenne’s cromornes have ten fingerholes, Nos. 7 and 8 being duplicates for right and left-handed players. They were probably sometimes used, as was the case with the hautbois de Poitou (see Bag-pipe), without the cap, when an extended compass was required.

The cromornes were in very general use in Europe from the 14th to the 17th century, and are to be found in illustrations of pageants, as for instance in the magnificent collection of woodcuts designed by Hans Burgmair, a pupil of Albrecht Dürer, representing the triumph of the emperor Maximilian,[1] where a bass and a tenor Krumbhorn player figure in the procession among countless other musicians. In the inventory of the wardrobe, &c., belonging to Henry VIII. at Westminster, made during the reign of Edward VI., we find eighteen crumhornes (see British Museum, Harleian MS. 1419, ff. 202b and 205). The cromornes did not always form an orchestra by themselves, but were also used in concert with other instruments and notably with flutes and oboes, as in municipal bands and in the private bands of princes. In 1685 the orchestra of the Neue Kirche at Strassburg comprised two tournebouts or cromornes, and until the middle of the 18th century these instruments formed part of the court band known as “Musique de la Grande Écurie” in the service of the French kings. They are first mentioned in the accounts for the year 1662, together with the tromba-marina, although the instrument was already highly esteemed in the 16th century. In that year five players of the cromorne were enrolled among the musicians of the Grande Écurie du Roi;[2] they received a yearly salary of 120 livres, which various supplementary allowances brought up to about 330 livres. In 1729 one of the cromorne players sold his appointment for 4000 francs. This was a sign of the failing popularity of the instrument. The duties of the cromorne and tromba-marina players consisted in playing in the great divertissements and at court functions and festivals in honour of royal marriages, births and thanksgivings.

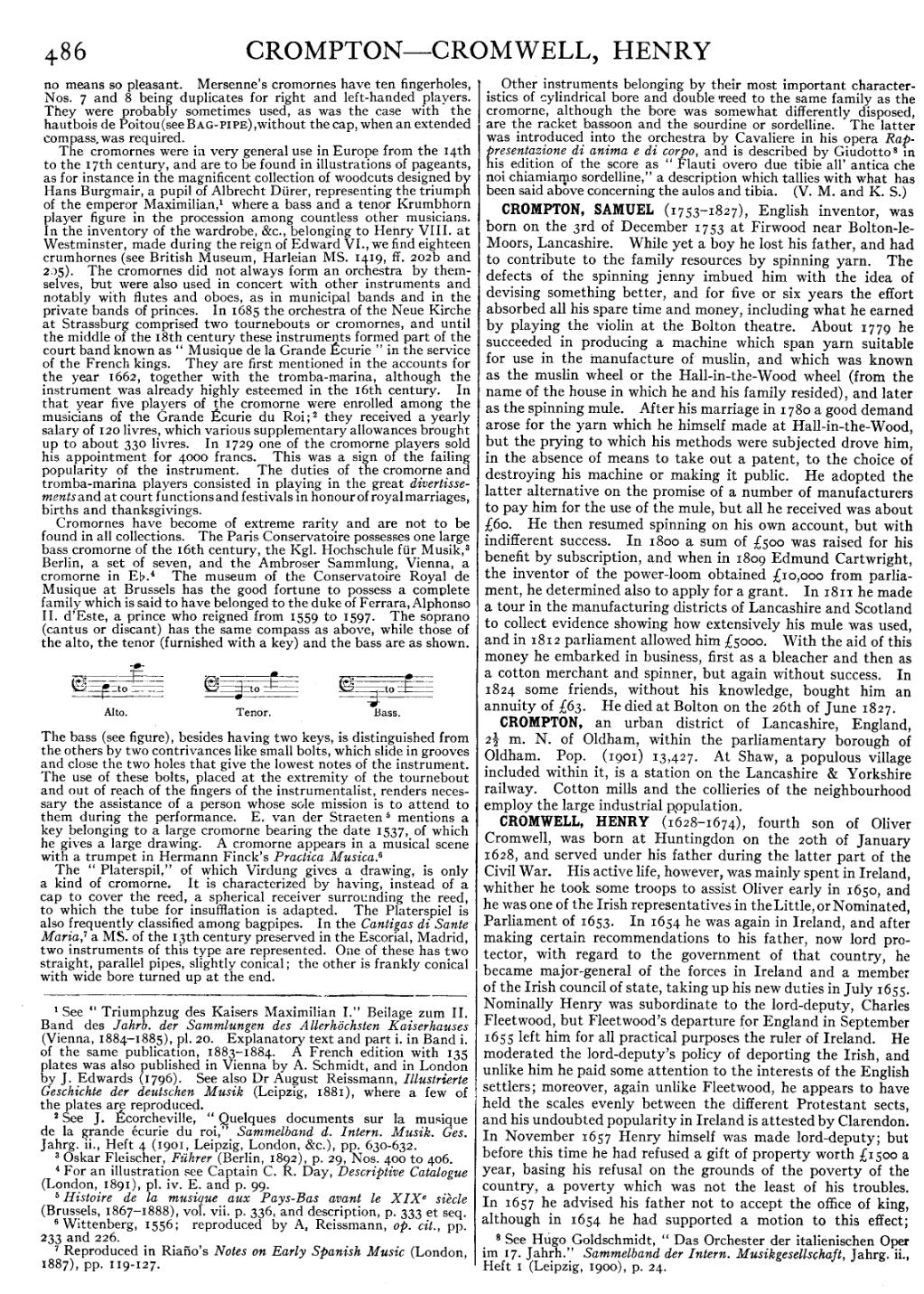

Cromornes have become of extreme rarity and are not to be found in all collections. The Paris Conservatoire possesses one large bass cromorne of the 16th century, the Kgl. Hochschule für Musik,[3] Berlin, a set of seven, and the Ambroser Sammlung, Vienna, a cromorne in E♭.[4] The museum of the Conservatoire Royal de Musique at Brussels has the good fortune to possess a complete family which is said to have belonged to the duke of Ferrara, Alphonso II. d’Este, a prince who reigned from 1559 to 1597. The soprano (cantus or discant) has the same compass as above, while those of the alto, the tenor (furnished with a key) and the bass are as shown.

| Alto. | Tenor. | Bass. |

The bass (see figure), besides having two keys, is distinguished from the others by two contrivances like small bolts, which slide in grooves and close the two holes that give the lowest notes of the instrument. The use of these bolts, placed at the extremity of the tournebout and out of reach of the fingers of the instrumentalist, renders necessary the assistance of a person whose sole mission is to attend to them during the performance. E. van der Straeten[5] mentions a key belonging to a large cromorne bearing the date 1537, of which he gives a large drawing. A cromorne appears in a musical scene with a trumpet in Hermann Finck’s Practica Musica.[6]

The “Platerspil,” of which Virdung gives a drawing, is only a kind of cromorne. It is characterized by having, instead of a cap to cover the reed, a spherical receiver surrounding the reed, to which the tube for insufflation is adapted. The Platerspiel is also frequently classified among bagpipes. In the Cantigas di Sante Maria,[7] a MS. of the 13th century preserved in the Escorial, Madrid, two instruments of this type are represented. One of these has two straight, parallel pipes, slightly conical; the other is frankly conical with wide bore turned up at the end.

Other instruments belonging by their most important characteristics of cylindrical bore and double reed to the same family as the cromorne, although the bore was somewhat differently disposed, are the racket bassoon and the sourdine or sordelline. The latter was introduced into the orchestra by Cavaliere in his opera Rappresentazione di anima e di corpo, and is described by Giudotto[8] in his edition of the score as “Flauti overo due tibie all’ antica che noi chiamiamo sordelline,” a description which tallies with what has been said above concerning the aulos and tibia. (V. M.; K. S.)

CROMPTON, SAMUEL (1753–1827), English inventor, was

born on the 3rd of December 1753 at Firwood near Bolton-le-Moors,

Lancashire. While yet a boy he lost his father, and had

to contribute to the family resources by spinning yarn. The

defects of the spinning jenny imbued him with the idea of

devising something better, and for five or six years the effort

absorbed all his spare time and money, including what he earned

by playing the violin at the Bolton theatre. About 1779 he

succeeded in producing a machine which span yarn suitable

for use in the manufacture of muslin, and which was known

as the muslin wheel or the Hall-in-the-Wood wheel (from the

name of the house in which he and his family resided), and later

as the spinning mule. After his marriage in 1780 a good demand

arose for the yarn which he himself made at Hall-in-the-Wood,

but the prying to which his methods were subjected drove him,

in the absence of means to take out a patent, to the choice of

destroying his machine or making it public. He adopted the

latter alternative on the promise of a number of manufacturers

to pay him for the use of the mule, but all he received was about

£60. He then resumed spinning on his own account, but with

indifferent success. In 1800 a sum of £500 was raised for his

benefit by subscription, and when in 1809 Edmund Cartwright,

the inventor of the power-loom obtained £10,000 from parliament,

he determined also to apply for a grant. In 1811 he made

a tour in the manufacturing districts of Lancashire and Scotland

to collect evidence showing how extensively his mule was used,

and in 1812 parliament allowed him £5000. With the aid of this

money he embarked in business, first as a bleacher and then as

a cotton merchant and spinner, but again without success. In

1824 some friends, without his knowledge, bought him an

annuity of £63. He died at Bolton on the 26th of June 1827.

CROMPTON, an urban district of Lancashire, England,

212 m. N. of Oldham, within the parliamentary borough of

Oldham. Pop. (1901) 13,427. At Shaw, a populous village

included within it, is a station on the Lancashire & Yorkshire

railway. Cotton mills and the collieries of the neighbourhood

employ the large industrial population.

CROMWELL, HENRY (1628–1674), fourth son of Oliver Cromwell, was born at Huntingdon on the 20th of January 1628, and served under his father during the latter part of the Civil War. His active life, however, was mainly spent in Ireland, whither he took some troops to assist Oliver early in 1650, and he was one of the Irish representatives in the Little, or Nominated, Parliament of 1653. In 1654 he was again in Ireland, and after making certain recommendations to his father, now lord protector, with regard to the government of that country, he became major-general of the forces in Ireland and a member of the Irish council of state, taking up his new duties in July 1655. Nominally Henry was subordinate to the lord-deputy, Charles Fleetwood, but Fleetwood’s departure for England in September 1655 left him for all practical purposes the ruler of Ireland. He moderated the lord-deputy’s policy of deporting the Irish, and unlike him he paid some attention to the interests of the English settlers; moreover, again unlike Fleetwood, he appears to have held the scales evenly between the different Protestant sects, and his undoubted popularity in Ireland is attested by Clarendon. In November 1657 Henry himself was made lord-deputy; but before this time he had refused a gift of property worth £1500 a year, basing his refusal on the grounds of the poverty of the country, a poverty which was not the least of his troubles. In 1657 he advised his father not to accept the office of king, although in 1654 he had supported a motion to this effect;

- ↑ See “Triumphzug des Kaisers Maximilian I.” Beilage zum II. Band des Jahrb. der Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses (Vienna, 1884–1885), pl. 20. Explanatory text and part i. in Band i. of the same publication, 1883–1884. A French edition with 135 plates was also published in Vienna by A. Schmidt, and in London by J. Edwards (1796). See also Dr August Reissmann, Illustrierte Geschichte der deutschen Musik (Leipzig, 1881), where a few of the plates are reproduced.

- ↑ See J. Écorcheville, “Quelques documents sur la musique de la grande écurie du roi,” Sammelband d. Intern. Musik. Ges. Jahrg. ii., Heft 4 (1901, Leipzig, London, &c.), pp. 630-632.

- ↑ Oskar Fleischer, Führer (Berlin, 1892), p. 29, Nos. 400 to 406.

- ↑ For an illustration see Captain C. R. Day, Descriptive Catalogue (London, 1891), pl. iv. E. and p. 99.

- ↑ Histoire de la musique aux Pays-Bas avant le XIX e siècle (Brussels, 1867–1888), vol. vii. p. 336, and description, p. 333 et seq.

- ↑ Wittenberg, 1556; reproduced by A. Reissmann, op. cit., pp. 233 and 226.

- ↑ Reproduced in Riaño’s Notes on Early Spanish Music (London, 1887), pp. 119-127.

- ↑ See Hugo Goldschmidt, “Das Orchester der italienischen Oper im 17. Jahrh.” Sammelband der Intern. Musikgesellschaft, Jahrg. ii., Heft 1 (Leipzig, 1900), p. 24.