courts, however, wholly disregarded such agreements, and considered them as affording no answer to a suit for restitution of conjugal rights. For a considerable period the court of chancery refused to enforce the covenant in such deeds by restraining the parties from proceeding to the ecclesiastical courts. But at last a memorable judgment of Lord Westbury (1861) asserted the right (Hunt v. Hunt, 4 De G. F. & J. 221; see also Marshall v. Marshall, 5 P. D. 19) of the court of chancery to maintain the claim of good faith in this as in other cases, and restrained a petitioner from suing in the ecclesiastical court contrary to his covenant. Thereafter these deeds became common, and no doubt often afford a solution of matrimonial difficulties of very great value. When the courts of the country became united under the Judicature Acts, it became practicable to set up in the divorce division a separation deed in answer to a suit for restitution of conjugal rights without the necessity of recourse to any other tribunal.

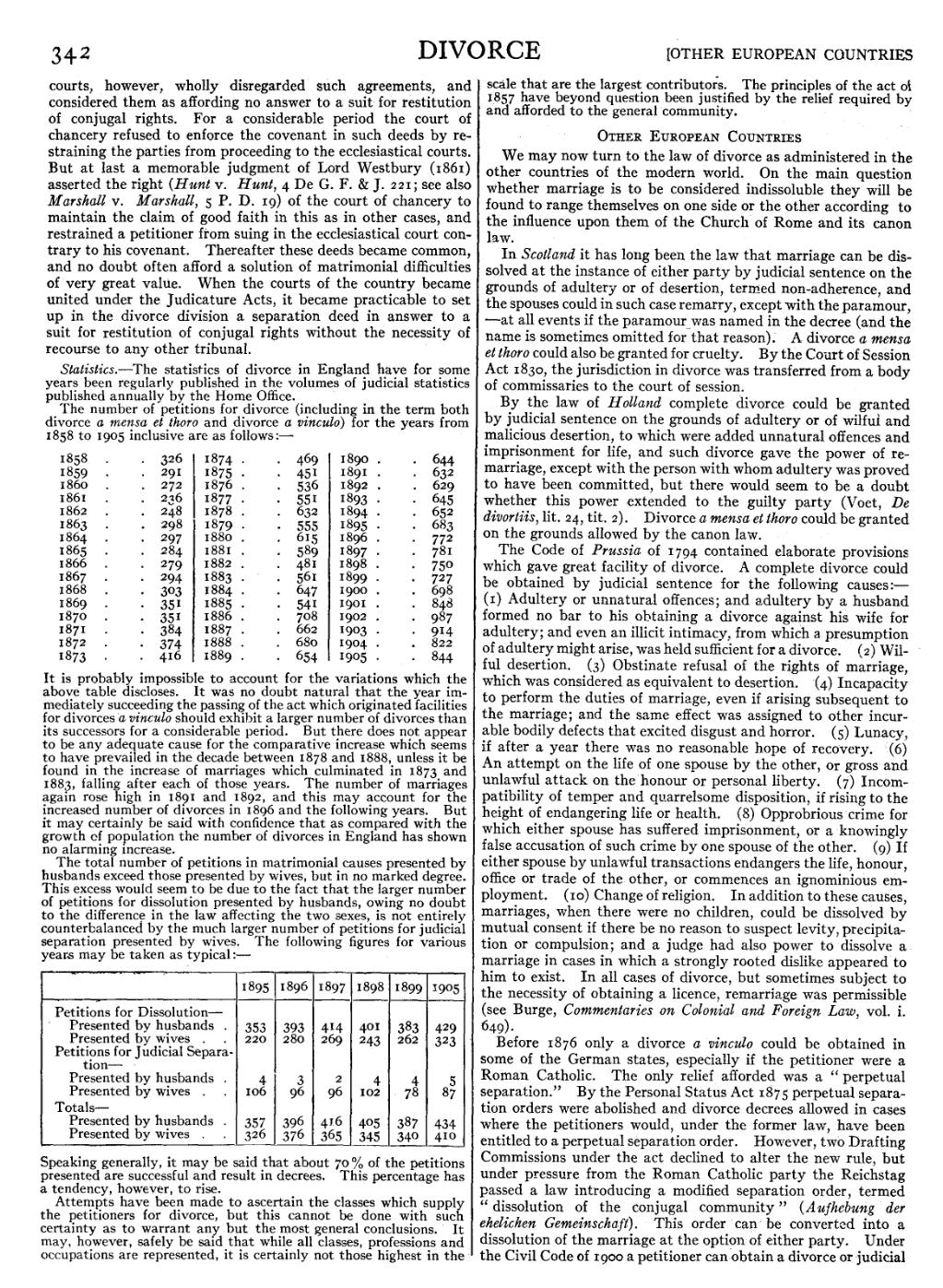

Statistics.—The statistics of divorce in England have for some years been regularly published in the volumes of judicial statistics published annually by the Home Office.

The number of petitions for divorce (including in the term both divorce a mensa et thoro and divorce a vinculo) for the years from 1858 to 1905 inclusive are as follows:—

| 1858 | 326 | 1874 | 469 | 1890 | 644 |

| 1859 | 291 | 1875 | 451 | 1891 | 632 |

| 1860 | 272 | 1876 | 536 | 1892 | 629 |

| 1861 | 236 | 1877 | 551 | 1893 | 645 |

| 1862 | 248 | 1878 | 632 | 1894 | 652 |

| 1863 | 298 | 1879 | 555 | 1895 | 683 |

| 1864 | 297 | 1880 | 615 | 1896 | 772 |

| 1865 | 284 | 1881 | 589 | 1897 | 781 |

| 1866 | 279 | 1882 | 481 | 1898 | 750 |

| 1867 | 294 | 1883 | 561 | 1899 | 727 |

| 1868 | 303 | 1884 | 647 | 1900 | 698 |

| 1869 | 351 | 1885 | 541 | 1901 | 848 |

| 1870 | 351 | 1886 | 708 | 1902 | 987 |

| 1871 | 384 | 1887 | 662 | 1903 | 914 |

| 1872 | 374 | 1888 | 680 | 1904 | 822 |

| 1873 | 416 | 1889 | 654 | 1905 | 844 |

It is probably impossible to account for the variations which the above table discloses. It was no doubt natural that the year immediately succeeding the passing of the act which originated facilities for divorces a vinculo should exhibit a larger number of divorces than its successors for a considerable period. But there does not appear to be any adequate cause for the comparative increase which seems to have prevailed in the decade between 1878 and 1888, unless it be found in the increase of marriages which culminated in 1873 and 1883, falling after each of those years. The number of marriages again rose high in 1891 and 1892, and this may account for the increased number of divorces in 1896 and the following years. But it may certainly be said with confidence that as compared with the growth of population the number of divorces in England has shown no alarming increase.

The total number of petitions in matrimonial causes presented by husbands exceed those presented by wives, but in no marked degree. This excess would seem to be due to the fact that the larger number of petitions for dissolution presented by husbands, owing no doubt to the difference in the law affecting the two sexes, is not entirely counterbalanced by the much larger number of petitions for judicial separation presented by wives. The following figures for various years may be taken as typical:—

| 1895 | 1896 | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 | 1905 | |

| Petitions for Dissolution— | ||||||

| Presented by husbands | 353 | 393 | 414 | 401 | 383 | 429 |

| Presented by wives | 220 | 280 | 269 | 243 | 262 | 23 |

| Petitions for Judicial Separation— | ||||||

| Presented by husbands | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Presented by wives | 106 | 96 | 96 | 102 | 78 | 87 |

| Totals— | ||||||

| Presented by husbands | 357 | 396 | 416 | 405 | 387 | 434 |

| Presented by wives | 326 | 376 | 365 | 345 | 340 | 410 |

Speaking generally, it may be said that about 70% of the petitions presented are successful and result in decrees. This percentage has a tendency, however, to rise.

Attempts have been made to ascertain the classes which supply the petitioners for divorce, but this cannot be done with such certainty as to warrant any but the most general conclusions. It may, however, safely be said that while all classes, professions and occupations are represented, it is certainly not those highest in the scale that are the largest contributors. The principles of the act of 1857 have beyond question been justified by the relief required by and afforded to the general community.

Other European Countries

We may now turn to the law of divorce as administered in the other countries of the modern world. On the main question whether marriage is to be considered indissoluble they will be found to range themselves on one side or the other according to the influence upon them of the Church of Rome and its canon law.

In Scotland it has long been the law that marriage can be dissolved at the instance of either party by judicial sentence on the grounds of adultery or of desertion, termed non-adherence, and the spouses could in such case remarry, except with the paramour,—at all events if the paramour was named in the decree (and the name is sometimes omitted for that reason). A divorce a mensa et thoro could also be granted for cruelty. By the Court of Session Act 1830, the jurisdiction in divorce was transferred from a body of commissaries to the court of session.

By the law of Holland complete divorce could be granted by judicial sentence on the grounds of adultery or of wilful and malicious desertion, to which were added unnatural offences and imprisonment for life, and such divorce gave the power of remarriage, except with the person with whom adultery was proved to have been committed, but there would seem to be a doubt whether this power extended to the guilty party (Voet, De divortiis, lit. 24, tit. 2). Divorce a mensa et thoro could be granted on the grounds allowed by the canon law.

The Code of Prussia of 1794 contained elaborate provisions which gave great facility of divorce. A complete divorce could be obtained by judicial sentence for the following causes:—(1) Adultery or unnatural offences; and adultery by a husband formed no bar to his obtaining a divorce against his wife for adultery; and even an illicit intimacy, from which a presumption of adultery might arise, was held sufficient for a divorce. (2) Wilful desertion. (3) Obstinate refusal of the rights of marriage, which was considered as equivalent to desertion. (4) Incapacity to perform the duties of marriage, even if arising subsequent to the marriage; and the same effect was assigned to other incurable bodily defects that excited disgust and horror. (5) Lunacy, if after a year there was no reasonable hope of recovery. (6) An attempt on the life of one spouse by the other, or gross and unlawful attack on the honour or personal liberty. (7) Incompatibility of temper and quarrelsome disposition, if rising to the height of endangering life or health. (8) Opprobrious crime for which either spouse has suffered imprisonment, or a knowingly false accusation of such crime by one spouse of the other. (9) If either spouse by unlawful transactions endangers the life, honour, office or trade of the other, or commences an ignominious employment. (10) Change of religion. In addition to these causes, marriages, when there were no children, could be dissolved by mutual consent if there be no reason to suspect levity, precipitation or compulsion; and a judge had also power to dissolve a marriage in cases in which a strongly rooted dislike appeared to him to exist. In all cases of divorce, but sometimes subject to the necessity of obtaining a licence, remarriage was permissible (see Burge, Commentaries on Colonial and Foreign Law, vol. i. 649).

Before 1876 only a divorce a vinculo could be obtained in some of the German states, especially if the petitioner were a Roman Catholic. The only relief afforded was a “perpetual separation.” By the Personal Status Act 1875 perpetual separation orders were abolished and divorce decrees allowed in cases where the petitioners would, under the former law, have been entitled to a perpetual separation order. However, two Drafting Commissions under the act declined to alter the new rule, but under pressure from the Roman Catholic party the Reichstag passed a law introducing a modified separation order, termed “dissolution of the conjugal community” (Aufhebung der ehelichen Gemeinschaft). This order can be converted into a dissolution of the marriage at the option of either party. Under the Civil Code of 1900 a petitioner can obtain a divorce or judicial