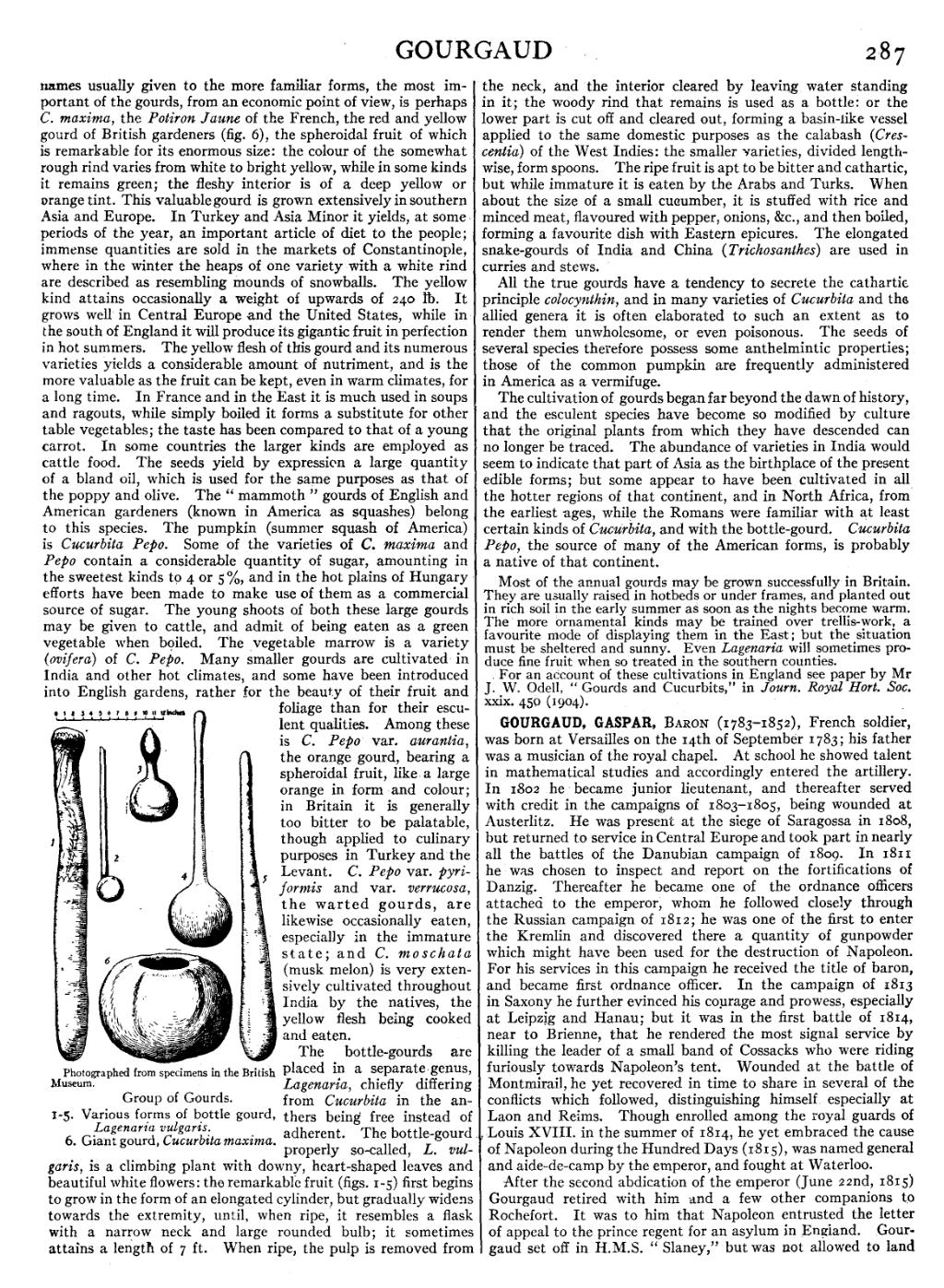

names usually given to the more familiar forms, the most important of the gourds, from an economic point of view, is perhaps C. maxima, the Potiron Jaune of the French, the red and yellow gourd of British gardeners (fig. 6), the spheroidal fruit of which is remarkable for its enormous size: the colour of the somewhat rough rind varies from white to bright yellow, while in some kinds it remains green; the fleshy interior is of a deep yellow or orange tint. This valuable gourd is grown extensively in southern Asia and Europe. In Turkey and Asia Minor it yields, at some periods of the year, an important article of diet to the people; immense quantities are sold in the markets of Constantinople, where in the winter the heaps of one variety with a white rind are described as resembling mounds of snowballs. The yellow kind attains occasionally a weight of upwards of 240 ℔. It grows well in Central Europe and the United States, while in the south of England it will produce its gigantic fruit in perfection in hot summers. The yellow flesh of this gourd and its numerous varieties yields a considerable amount of nutriment, and is the more valuable as the fruit can be kept, even in warm climates, for a long time. In France and in the East it is much used in soups and ragouts, while simply boiled it forms a substitute for other table vegetables; the taste has been compared to that of a young carrot. In some countries the larger kinds are employed as cattle food. The seeds yield by expression a large quantity of a bland oil, which is used for the same purposes as that of the poppy and olive. The “mammoth” gourds of English and American gardeners (known in America as squashes) belong to this species. The pumpkin (summer squash of America) is Cucurbita Pepo. Some of the varieties of C. maxima and Pepo contain a considerable quantity of sugar, amounting in the sweetest kinds to 4 or 5%, and in the hot plains of Hungary efforts have been made to make use of them as a commercial source of sugar. The young shoots of both these large gourds may be given to cattle, and admit of being eaten as a green vegetable when boiled. The vegetable marrow is a variety (ovifera) of C. Pepo. Many smaller gourds are cultivated in India and other hot climates, and some have been introduced into English gardens, rather for the beauty of their fruit and foliage than for their esculent qualities. Among these is C. Pepo var. aurantia, the orange gourd, bearing a spheroidal fruit, like a large orange in form and colour; in Britain it is generally too bitter to be palatable, though applied to culinary purposes in Turkey and the Levant. C. Pepo var. pyriformis and var. verrucosa, the warted gourds, are likewise occasionally eaten, especially in the immature state; and C. moschata (musk melon) is very extensively cultivated throughout India by the natives, the yellow flesh being cooked and eaten.

|

Photographed from specimens in the British Museum. Group of Gourds. 1-5. Various forms of bottle gourd,Lagenaria vulgaris. |

The bottle-gourds are placed in a separate genus, Lagenaria, chiefly differing from Cucurbita in the anthers being free instead of adherent. The bottle-gourd properly so-called, L. vulgaris, is a climbing plant with downy, heart-shaped leaves and beautiful white flowers: the remarkable fruit (figs. 1-5) first begins to grow in the form of an elongated cylinder, but gradually widens towards the extremity, until, when ripe, it resembles a flask with a narrow neck and large rounded bulb; it sometimes attains a length of 7 ft. When ripe, the pulp is removed from the neck, and the interior cleared by leaving water standing in it; the woody rind that remains is used as a bottle: or the lower part is cut off and cleared out, forming a basin-like vessel applied to the same domestic purposes as the calabash (Crescentia) of the West Indies: the smaller varieties, divided lengthwise, form spoons. The ripe fruit is apt to be bitter and cathartic, but while immature it is eaten by the Arabs and Turks. When about the size of a small cucumber, it is stuffed with rice and minced meat, flavoured with pepper, onions, &c., and then boiled, forming a favourite dish with Eastern epicures. The elongated snake-gourds of India and China (Trichosanthes) are used in curries and stews.

All the true gourds have a tendency to secrete the cathartic principle colocynthin, and in many varieties of Cucurbita and the allied genera it is often elaborated to such an extent as to render them unwholesome, or even poisonous. The seeds of several species therefore possess some anthelmintic properties; those of the common pumpkin are frequently administered in America as a vermifuge.

The cultivation of gourds began far beyond the dawn of history, and the esculent species have become so modified by culture that the original plants from which they have descended can no longer be traced. The abundance of varieties in India would seem to indicate that part of Asia as the birthplace of the present edible forms; but some appear to have been cultivated in all the hotter regions of that continent, and in North Africa, from the earliest ages, while the Romans were familiar with at least certain kinds of Cucurbita, and with the bottle-gourd. Cucurbita Pepo, the source of many of the American forms, is probably a native of that continent.

Most of the annual gourds may be grown successfully in Britain. They are usually raised in hotbeds or under frames, and planted out in rich soil in the early summer as soon as the nights become warm. The more ornamental kinds may be trained over trellis-work, a favourite mode of displaying them in the East; but the situation must be sheltered and sunny. Even Lagenaria will sometimes produce fine fruit when so treated in the southern counties.

For an account of these cultivations in England see paper by Mr J. W. Odell, “Gourds and Cucurbits,” in Journ. Royal Hort. Soc. xxix. 450 (1904).

GOURGAUD, GASPAR, Baron (1783–1852), French soldier, was born at Versailles on the 14th of September 1783; his father was a musician of the royal chapel. At school he showed talent in mathematical studies and accordingly entered the artillery. In 1802 he became junior lieutenant, and thereafter served with credit in the campaigns of 1803–1805, being wounded at Austerlitz. He was present at the siege of Saragossa in 1808, but returned to service in Central Europe and took part in nearly all the battles of the Danubian campaign of 1809. In 1811 he was chosen to inspect and report on the fortifications of Danzig. Thereafter he became one of the ordnance officers attached to the emperor, whom he followed closely through the Russian campaign of 1812; he was one of the first to enter the Kremlin and discovered there a quantity of gunpowder which might have been used for the destruction of Napoleon. For his services in this campaign he received the title of baron, and became first ordnance officer. In the campaign of 1813 in Saxony he further evinced his courage and prowess, especially at Leipzig and Hanau; but it was in the first battle of 1814, near to Brienne, that he rendered the most signal service by killing the leader of a small band of Cossacks who were riding furiously towards Napoleon’s tent. Wounded at the battle of Montmirail, he yet recovered in time to share in several of the conflicts which followed, distinguishing himself especially at Laon and Reims. Though enrolled among the royal guards of Louis XVIII. in the summer of 1814, he yet embraced the cause of Napoleon during the Hundred Days (1815), was named general and aide-de-camp by the emperor, and fought at Waterloo.

After the second abdication of the emperor (June 22nd, 1815) Gourgaud retired with him and a few other companions to Rochefort. It was to him that Napoleon entrusted the letter of appeal to the prince regent for an asylum in England. Gourgaud set off in H.M.S. “Slaney,” but was not allowed to land