and in consequence of their excellent construction many houses of the 16th and 17th centuries have remained in good preservation down to the present day; they are found in the Cotswolds generally, and (among small towns) at Broadway in Worcestershire and (of brick) throughout Essex and Suffolk. Among the larger half-timber houses built in the 15th and 16th centuries, mention may be made of Bramhall Hall, near Manchester; Speke Hall, near Liverpool (see Plate III., fig. 10); The Oaks; West Bromwich; and Moreton Old Hall, Cheshire, one of the most elaborate of the series (see Plate III., fig. 11).

|

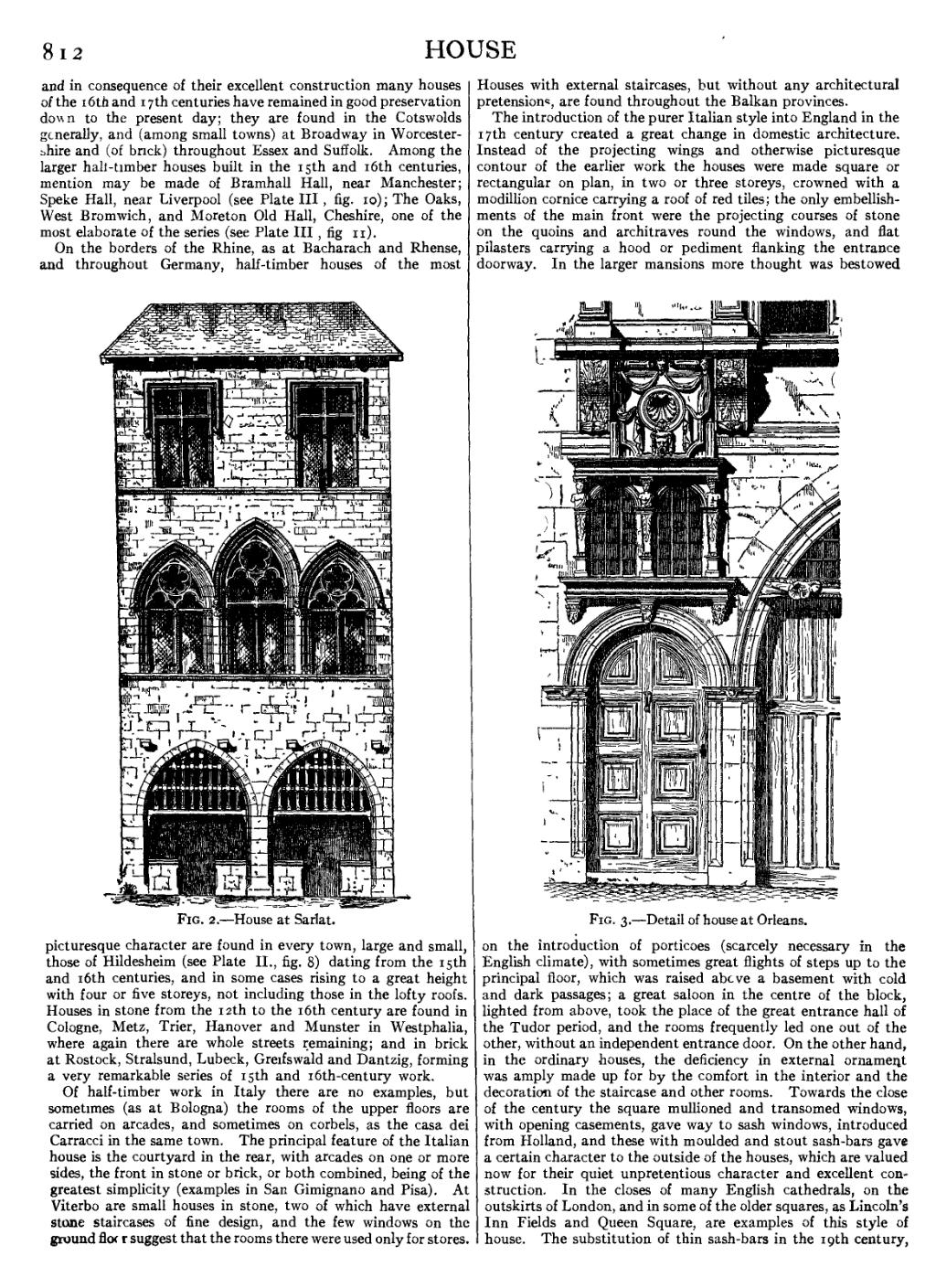

| Fig. 2.—House at Sarlat. |

On the borders of the Rhine, as at Bacharach and Rhense, and throughout Germany, half-timber houses of the most picturesque character are found in every town, large and small, those of Hildesheim (see Plate II., fig. 8) dating from the 15th and 16th centuries, and in some cases rising to a great height with four or five storeys, not including those in the lofty roofs. Houses in stone from the 12th to the 16th century are found in Cologne, Metz, Trier, Hanover and Münster in Westphalia, where again there are whole streets remaining; and in brick at Rostock, Stralsund, Lübeck, Greifswald and Dantzig, forming a very remarkable series of 15th and 16th-century work.

Of half-timber work in Italy there are no examples, but sometimes (as at Bologna) the rooms of the upper floors are carried on arcades, and sometimes on corbels, as the casa dei Carracci in the same town. The principal feature of the Italian house is the courtyard in the rear, with arcades on one or more sides, the front in stone or brick, or both combined, being of the greatest simplicity (examples in San Gimignano and Pisa). At Viterbo are small houses in stone, two of which have external stone staircases of fine design, and the few windows on the ground floor suggest that the rooms there were used only for stores. Houses with external staircases, but without any architectural pretensions, are found throughout the Balkan provinces.

|

| Fig. 3.—Detail of house at Orleans. |

The introduction of the purer Italian style into England in the 17th century created a great change in domestic architecture. Instead of the projecting wings and otherwise picturesque contour of the earlier work the houses were made square or rectangular on plan, in two or three storeys, crowned with a modillion cornice carrying a roof of red tiles; the only embellishments of the main front were the projecting courses of stone on the quoins and architraves round the windows, and flat pilasters carrying a hood or pediment flanking the entrance doorway. In the larger mansions more thought was bestowed on the introduction of porticoes (scarcely necessary in the English climate), with sometimes great flights of steps up to the principal floor, which was raised above a basement with cold and dark passages; a great saloon in the centre of the block, lighted from above, took the place of the great entrance hall of the Tudor period, and the rooms frequently led one out of the other, without an independent entrance door. On the other hand, in the ordinary houses, the deficiency in external ornament was amply made up for by the comfort in the interior and the decoration of the staircase and other rooms. Towards the close of the century the square mullioned and transomed windows, with opening casements, gave way to sash windows, introduced from Holland, and these with moulded and stout sash-bars gave a certain character to the outside of the houses, which are valued now for their quiet unpretentious character and excellent construction. In the closes of many English cathedrals, on the outskirts of London, and in some of the older squares, as Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Queen Square, are examples of this style of house. The substitution of thin sash-bars in the 19th century,