The simplest classification of mosaics is that of Gauckler

(Daremberg and Saglio, Dictionnaire des antiquités, s.v. “Musivum

Opus”), who distinguishes the following:—

a. Opus tessellatum, consisting of cubes of marble or stone, regularly disposed in simple patterns. This was largely used for pavements, especially in Roman times.

Fig. 1.—Greek Pavement from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia.

b. Opus vermiculatum, consisting of cubes (not always regularly shaped) generally of coloured marble[1] or more precious materials, when these were obtainable, disposed so as to obtain a pictorial effect. The art of mosaic is mainly concerned with this branch of work.

c. Opus musivum, properly applied to the mosaic decoration of walls and vaulted ceilings (camerae), in which cubes of glass or enamel were used. The glass was rendered opaque by the addition of oxide of tin, and coloured with other metallic oxides; when melted it was cast into flat slabs, generally about 12 in. thick, and then broken into small cubes.

d. Opus sectile, a species of marqueterie in marble or other coloured materials used to produce pictures and patterns. Under the later empire a particular variety of this, called opus alexandrinum[2] mainly composed of porphyry, red and green,[3] was much in use.

Judging from the description given by Vitruvius (vii. 1), and an examination of numerous specimens of Roman tessellated mosaics, the process of manufacture was the following. The earth was first carefully rammed down to a firm and even surface; on this was laid a thick bed of stones, dry rubbish, and lime, called “rudus,” from 6 to 9 in. deep, and above this another layer, 4 to 6 in. thick, called “nucleus,” of one part of lime to three of pounded brick, mixed with water; on this, while still soft, the pattern could be sketched out with a wooden or metal point, and the tesserae or small bits of marble stuck into it, with their smoothest side uppermost. Lime, pounded white marble, and water were then mixed to the consistency of cream, forming a very hard-setting cement, called marmoratum. This cement, while fluid, was poured over the marble surface, and well brushed into all the interstices between the tesserae. When the concrete and cement were both set, the surface of the pavement was rubbed down and polished.

The usual Roman pavement was made of pieces of marble, averaging from half to a quarter of an inch square, but rather irregular in shape. A few other, but quite exceptional, kinds of mosaic pavements have been found, such as that at the Isola Farnese, 9 m. from Rome, made of tile-like slabs of green glass, and a fine “sectile” pavement on the Palatine Hill, made of various-shaped pieces of glass, in black, white, and deep yellow. In some cases—e.g. in the “House of the Faun” at Pompeii—glass tesserae in small quantities have been mixed with the marble ones, for the sake of greater brilliance of colour.

Few countries are richer than England in remains of Roman mosaics; the great pavements of York, Woodchester, Cirencester, and many other places are as elaborate in design and as skilfully executed as any that now exist even in Rome itself. In whatever country these mosaics are found, their style and method of treatment are always much the same; the materials only of which the tesserae are made vary according to the stone or marble supplied by each country. In England, for instance, limestone or chalk often takes the place of the white marble so common in Italian and North African mosaics; while, instead of red marble, a fine sort of burnt clay or red sandstone is generally used; other makeshifts had to be resorted to, and many of the Romano-British mosaics are made entirely without marble. It is perhaps partly owing to the great wealth of Northern Africa in marbles of many colours and of varying shades that the finest of all Roman mosaics have been found in Algeria and Tunis, especially those from Carthage, some of which have been brought to the British Museum. See Archaeologia, xxxviii. 202.

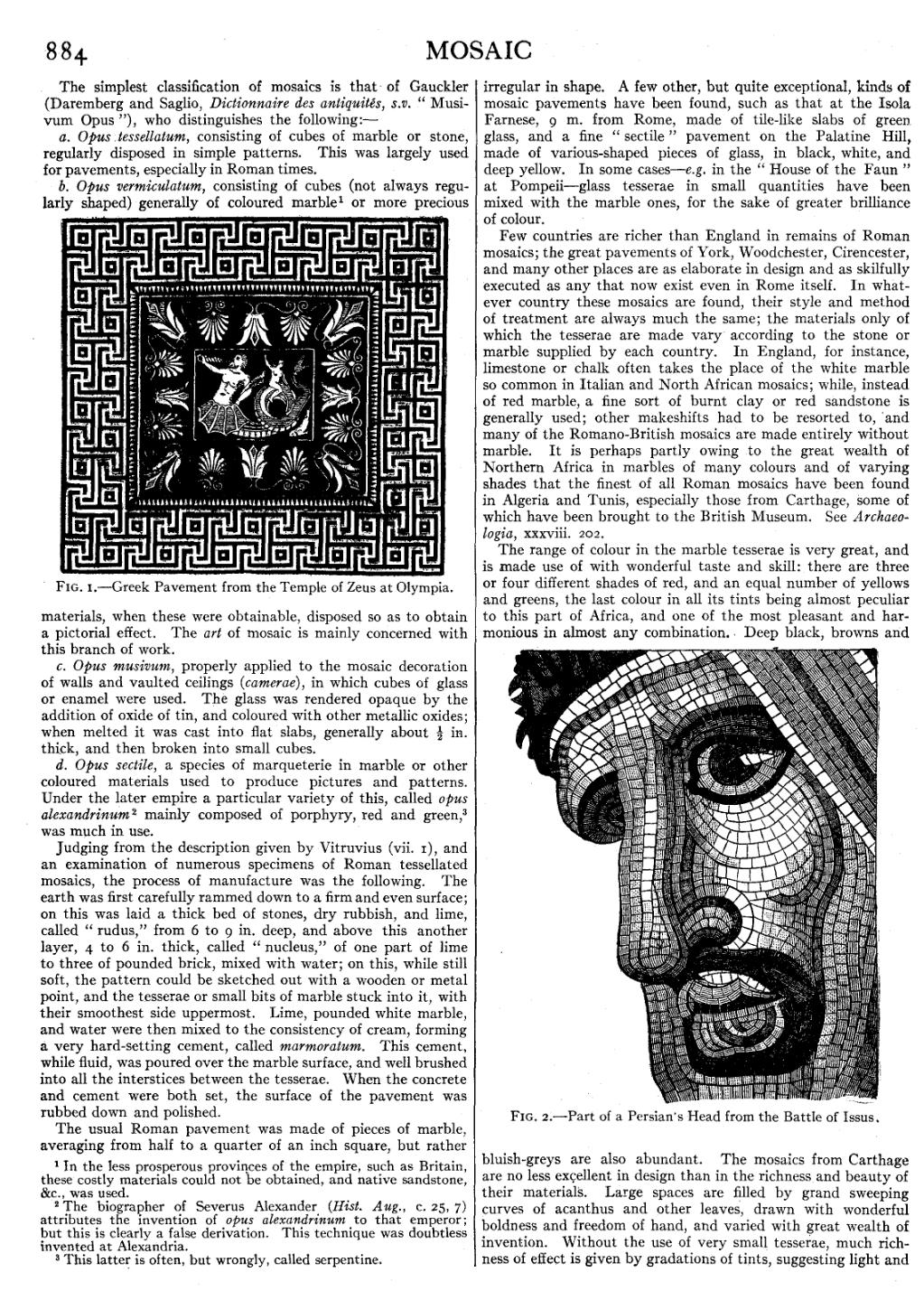

Fig. 2.—Part of a Persian’s Head from the Battle of Issus.

The range of colour in the marble tesserae is very great, and is made use of with wonderful taste and skill: there are three or four different shades of red, and an equal number of yellows and greens, the last colour in all its tints being almost peculiar to this part of Africa, and one of the most pleasant and harmonious in almost any combination Deep black, browns and bluish-greys are also abundant. The mosaics from Carthage are no less excellent in design than in the richness and beauty of their materials. Large spaces are filled by grand sweeping curves of acanthus and other leaves, drawn with wonderful boldness and freedom of hand, and varied with great wealth of invention. Without the use of very small tesserae, much richness of effect is given by gradations of tints, suggesting light and

- ↑ In the less prosperous provinces of the empire, such as Britain, these costly materials Could not be obtained, and native sandstone, &c., was used.

- ↑ The biographer of Severus Alexander (Hist. Aug., c. 25, 7) attributes the invention of opus alexandrinum to that emperor; but this is clearly a false derivation. This technique was doubtless invented at Alexandria.

- ↑ This latter is often, but wrongly, called serpentine.