autographic picture of the entire sphere containing more than fifty million stars, which should faithfully record in future ages the state of the sky at the end of the 19th century. Although he did not live to see its completion, he had the satisfaction of knowing that the ultimate success of this vast scheme was assured. He died suddenly at his country seat at Wissous, near Antony, on the 25th of June 1892.

See Month. Notices Roy. Astr. Society, liii. 226; Observatory, xv. 305 (D. Klumpke); Nature, xlvi. 253; Rapport annuel sur l’observatoire de Paris pour l’année 1892. (A. M. C.)

MOUFLON, or Muflon, the wild sheep (Ovis musimon) of

Corsica and Sardinia, where it is now very local. The ewes

are either hornless or provided with quite small horns, the

hornless form being probably characteristic of one island and

the horned of the other. The rams carry good horns, and in

summer show a conspicuous light saddle-shaped mark on the

otherwise dark-coloured coat. The Armenian mouflon (O.

orientalis), of Persia, Armenia, and the Tröodos range of Cyprus,

is typically a larger and redder sheep, with the horns curving

in the reverse direction; but the Cyprian race is small. (See

Sheep.)

MOULD. (1) (O. Eng. molde, from a Teutonic root meaning

to grind, reduce to powder, cf. “meal”), loose fine earth,

rich in organic matter, on the surface of cultivated ground,

especially the made garden soil suitable for the growth of plants.

In the sense of a furry growth, consisting of minute fungi found

on animal or vegetable substances exposed to damp, the word

may be either an extension of “mould,” earth, or an adaptation

of an early “moul,” with an additional d due to “mould.”

“Moul” is a Scandinavian word, cf. Swed. mögla, to grow musty,

and the Eng. colloquial “muggy.” (2) A form or pattern,

particularly one by means of which plastic materials may be

made into shapes, whence “moulding,” the form which the

material so shaped takes. The word comes through the O. Fr.

modle, molle, from Lat. modulus, a measure, or standard. The

English “model” is another derivative of the same word.

MOULDINGS, the term in architecture for the decorative treatment given to projecting or receding features in stone, wood and other materials, by means of curved forms, whereby those features are accentuated and varied owing to the play of light and shade on the surfaces. The principal characteristics

of all the European styles are to be found in the mouldings

employed in them and in their ornamental decoration; In

some of the earlier styles, such as the Assyrian and the Persian,

there are no mouldings: coloured bands in brick, enamelled tiles

or beton, were deemed sufficient to mark the divisions of their

storeys or to decorate their buildings. The Egyptians employed

two mouldings only, the cavetto (fig. 1), a deep moulding sometimes

of great dimensions which crowned their pylons, temples

and decorative shrines, and the torus, a semicircular projecting

moulding which was carried above the architrave and down

the quoins of their buildings. The Greeks were the first to

recognize, in their temples, the special value possessed by

mouldings which, occupying an intermediate position between

the ornamental sculptures and the simple architectural lines

of the main structure, gave a richly decorative effect to the

latter without interference with the beauty of the former.

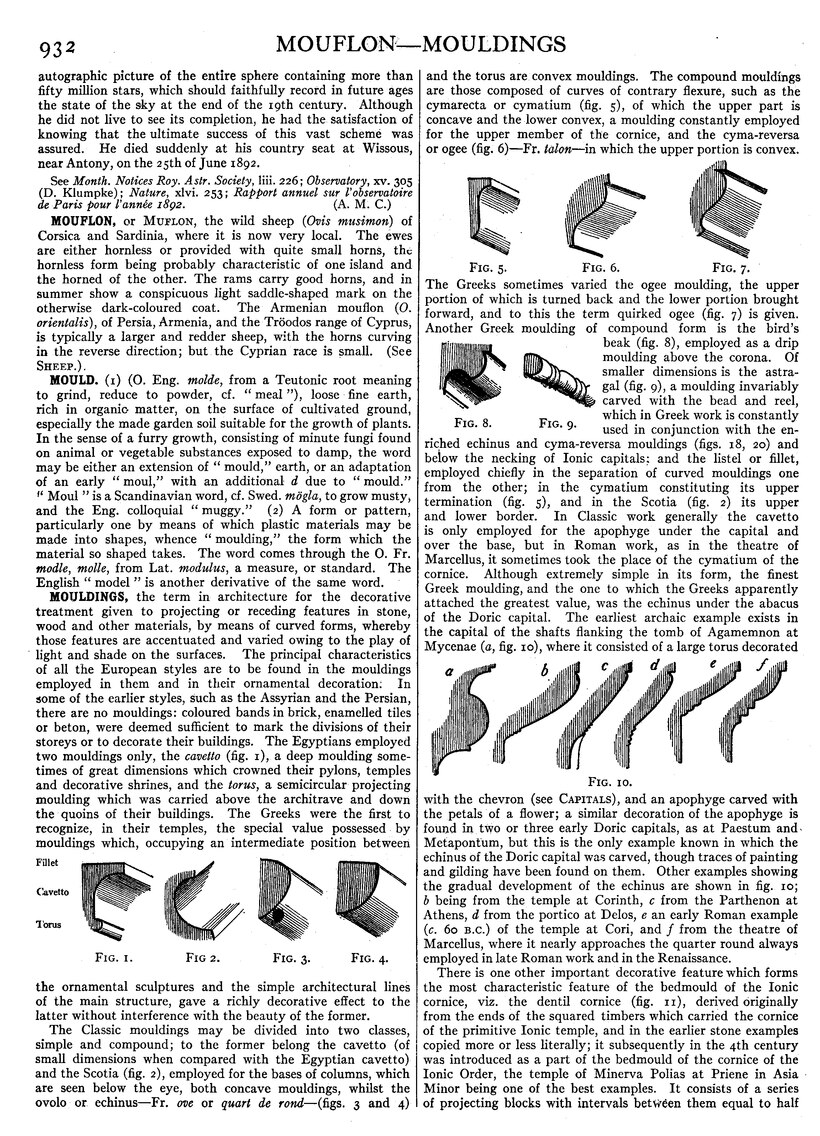

Fig. 1.Fig. 2.Fig. 3.Fig. 4.

The Classic mouldings may be divided into two classes, simple and compound; to the former belong the cavetto (of small dimensions when compared with the Egyptian cavetto) and the Scotia (fig. 2), employed for the bases of columns, which are seen below the eye, both concave mouldings, whilst the ovolo or echinus—Fr. ove or quart de rond—(figs. 3 and 4) and the torus are convex mouldings. The compound mouldings are those composed of curves of contrary flexure, such as the cymarecta or cymatium (fig. 5), of which the upper part is concave and the lower convex, a moulding constantly employed for the upper member of the cornice, and the cyma-reversa or ogee (fig. 6)—Fr. talon—in which the upper portion is convex.

Fig. 5.Fig. 6.Fig. 7.

| Fig. 8.Fig. 9. |

The Greeks sometimes varied the ogee moulding, the upper portion of which is turned back and the lower portion brought forward, and to this the term quirked ogee (fig. 7) is given. Another Greek moulding of compound form is the bird's beak (fig. 8), employed as a drip moulding above the corona. Of smaller dimensions is the astragal (fig. 9), a moulding invariably carved with the bead and reel, which in Greek work is constantly used in conjunction with the enriched echinus and cyma-reversa mouldings (figs. 18, 20) and below the necking of Ionic capitals; and the listel or fillet, employed chiefly in the separation of curved mouldings one from the other; in the cymatium constituting its upper termination (fig. 5), and in the Scotia (fig. 2) its upper and lower border. In Classic work generally the cavetto is only employed for the apophyge under the capital and over the base, but in Roman work, as in the theatre of Marcellus, it sometimes took the place of the cymatium of the cornice. Although extremely simple in its form, the finest Greek moulding, and the one to which the Greeks apparently attached the greatest value, was the echinus under the abacus of the Doric capital. The earliest archaic example exists in the capital of the shafts flanking the tomb of Agamemnon at Mycenae (a, fig. 10), where it consisted of a large torus decorated with the chevron (see Capitals), and an apophyge carved with the petals of a flower; a similar decoration of the apophyge is found in two or three early Doric capitals, as at Paestum and Metapontum, but this is the only example known in which the echinus of the Doric capital was carved, though traces of painting and gilding have been found on them. Other examples showing the gradual development of the echinus are shown in fig. 10; b being from the temple at Corinth, c from the Parthenon at Athens, d from the portico at Delos, e an early Roman example (c. 60 B.C.) of the temple at Cori, and f from the theatre of Marcellus, where it nearly approaches the quarter round always employed in late Roman work and in the Renaissance.

Fig. 10.

There is one other important decorative feature which forms the most characteristic feature of the bedmould of the Ionic cornice, viz. the dentil cornice (fig. 11), derived originally from the ends of the squared timbers which carried the cornice of the primitive Ionic temple, and in the earlier stone examples copied more or less literally; it subsequently in the 4th century was introduced as a part of the bedmould of the cornice of the Ionic Order, the temple of Minerva Polias at Priene in Asia Minor being one of the best examples. It consists of a series of projecting blocks with intervals between them equal to half