custom now to have the patient lying upon his back, with the head hanging over the end of the table, so that the blood may sink into the dome of the pharynx and escape by the nostrils, instead of running the risk of finding its way into the windpipe and lungs. (See Cleft Palate.)

Mumps.—Inflammation of the parotid gland is apt to occur as an epidemic, children being chiefly attacked. The disease, which is highly infectious, is called mumps, and is associated with much swelling below and in front of the ear, or ears. There is stiffness of the jaw and there is a difficulty in swallowing. There is slight local tenderness, and the temperature may, perhaps, run up a degree or two. For the sake of others, the child should be kept away from school for three or four weeks.

Salivary Calculus.—Sometimes a deposit of phosphate and carbonate of lime slowly takes place from the saliva, and gives rise to the formation of a small concretion in the duct of one of the salivary glands. When the concretion blocks the duct, so that the saliva is unable to find its way into the mouth, a fluid swelling forms behind the blockage, giving rise to inconvenience and unsightliness. The swelling is at its greatest during a meal, when the secretion of the saliva is necessarily rapid; subsequently it disappears, recurring, however, at the next meal-time. In many cases the patient is conscious of the fact of there being a hard, movable “kernel,” the size, perhaps, of a barleycorn, a cherry-stone or even of a small almond, in the course of the duct. In the removal of the calculus every endeavour should be made to effect its escape into the mouth, as, if the skin were incised for its extraction, the wound might refuse to heal, a salivary fistula resulting. (E. O.*)

MOUTHPIECE (Fr. embouchure; Ger. Mundstück; Ital.

bocchino), in music, that part of a wind instrument into which

the performer directs his breath in order to induce the regular

series of vibrations to which musical sounds are due. The

mouthpiece is either taken into the mouth or held to the lips;

by an extension of the meaning of the word, mouthpiece is also

applied to the corresponding part of an organ-pipe through

which the compressed wind is blown, and containing the sharp

edge known as “lip,” or the reed necessary for the production

of sound. The quality of a musical tone is due primarily to the

form or method of vibration by means of which sound-waves

of a distinctive character are generated, each consisting of a

pulse or half-wave of compression and of a pulse of rarefaction;

the variety in the quality of tone, or “timbre,” obtainable in

various wind instruments is in a great measure due to the form

and construction of the mouthpiece, taken in combination with

the form of the column of air within the tube and consequently

of the bore of the latter. The principal functions of the mouthpiece

are (1) to facilitate the production of the natural harmonic

scale of the instrument; (2) to assist in correcting errors in

pitch as the ear directs; (3) to enable the performer to obtain

the dynamic variations whereby he translates his emotional

interpretation of the music into sound. Mouthpieces, therefore,

serve as a means of classifying wind instruments. They fall

into the following divisions:—

|

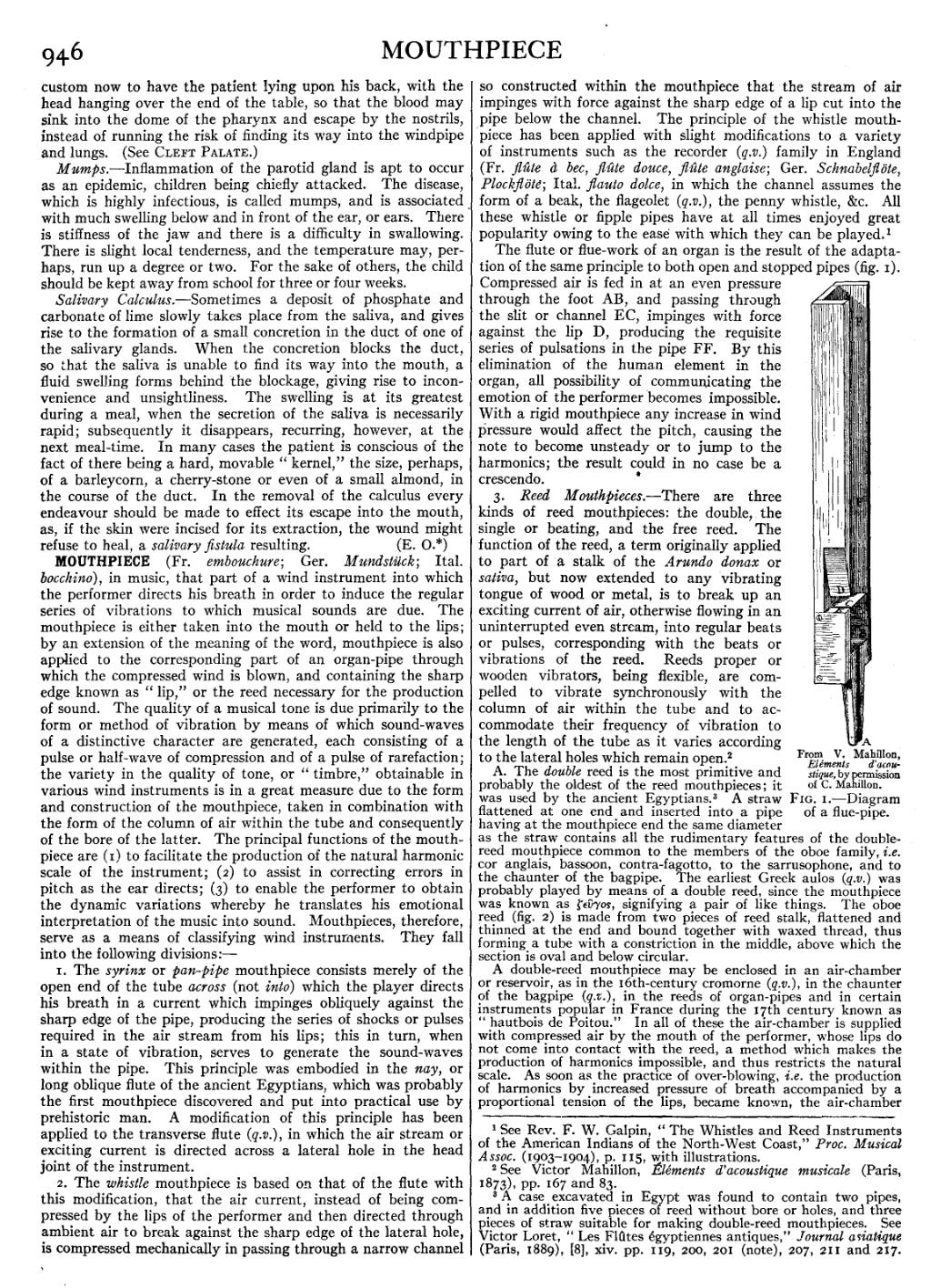

From V. Mahillon, Éléments d’acoustique, by permission of C. Mahillon.

|

| Fig. 1.—Diagram of a flue-pipe. |

1. The syrinx or pan-pipe mouthpiece consists merely of the open end of the tube across (not into) which the player directs his breath in a current which impinges obliquely against the sharp edge of the pipe, producing the series of shocks or pulses required in the air stream from his lips; this in turn, when in a state of vibration, serves to generate the sound-waves within the pipe. This principle was embodied in the nay, or long oblique flute of the ancient Egyptians, which was probably the first mouthpiece discovered and put into practical use by prehistoric man. A modification of this principle has been applied to the transverse flute (q.v.), in which the air stream or exciting current is directed across a lateral hole in the head joint of the instrument.

2. The whistle mouthpiece is based on that of the flute with this modification, that the air current, instead of being compressed by the lips of the performer and then directed through ambient air to break against the sharp edge of the lateral hole, is compressed mechanically in passing through a narrow channel so constructed within the mouthpiece that the stream of air impinges with force against the sharp edge of a lip cut into the pipe below the channel. The principle of the whistle mouthpiece has been applied with slight modifications to a variety of instruments such as the recorder (q.v.) family in England (Fr. flûte à bec, flûte douce, flûte anglaise; Ger. Schnabelflöte, Plockflöte; Ital. flauto dolce, in which the channel assumes the form of a beak, the flageolet (q.v.), the penny whistle, &c. All these whistle or fipple pipes have at all times enjoyed great popularity owing to the ease with which they can be played.[1]

The flute or flue-work of an organ is the result of the adaptation of the same principle to both open and stopped pipes (fig. 1). Compressed air is fed in at an even pressure through the foot AB, and passing through the slit or channel EC, impinges with force against the lip D, producing the requisite series of pulsations in the pipe FF. By this elimination of the human element in the organ, all possibility of communicating the emotion of the performer becomes impossible. With a rigid mouthpiece any increase in wind pressure would affect the pitch, causing the note to become unsteady or to jump to the harmonics; the result could in no case be a crescendo.

3. Reed Mouthpieces.—There are three kinds of reed mouthpieces: the double, the single or beating, and the free reed. The function of the reed, a term originally applied to part of a stalk of the Arundo donax or sativa, but now extended to any vibrating tongue of wood or metal, is to break up an exciting current of air, otherwise flowing in an uninterrupted even stream, into regular beats or pulses, corresponding with the beats or vibrations of the reed. Reeds proper or wooden vibrators, being flexible, are compelled to vibrate synchronously with the column of air within the tube and to accommodate their frequency of vibration to the length of the tube as it varies according to the lateral holes which remain open.[2]

A. The double reed is the most primitive and probably the oldest of the reed mouthpieces; it was used by the ancient Egyptians.[3] A straw flattened at one end and inserted into a pipe having at the mouthpiece end the same diameter as the straw contains all the rudimentary features of the double-reed mouthpiece common to the members of the oboe family, i.e. cor anglais, bassoon, contra-fagotto, to the sarrusophone, and to the chaunter of the bagpipe. The earliest Greek aulos (q.v.) was probably played by means of a double reed, since the mouthpiece was known as ζεῦγος, signifying a pair of like things. The oboe reed (fig. 2) is made from two pieces of reed stalk, flattened and thinned at the end and bound together with waxed thread, thus forming a tube with a constriction in the middle, above which the section is oval and below circular.

A double-reed mouthpiece may be enclosed in an air-chamber or reservoir, as in the 16th-century cromorne (q.v.), in the chaunter of the bagpipe (q.v.), in the reeds of organ-pipes and in certain instruments popular in France during the 17th century known as “hautbois de Poitou.” In all of these the air-chamber is supplied with compressed air by the mouth of the performer, whose lips do not come into contact with the reed, a method which makes the production of harmonics impossible, and thus restricts the natural scale. As soon as the practice of over-blowing, i.e. the production of harmonics by increased pressure of breath accompanied by a proportional tension of the lips, became known, the air-chamber

- ↑ See Rev. F. W. Galpin, “The Whistles and Reed Instruments of the American Indians of the North-West Coast,” Proc. Musical Assoc. (1903–1904), p. 115, with illustrations.

- ↑ See Victor Mahillon, Éléments d’acoustique musicale (Paris, 1873), pp. 167 and 83.

- ↑ A case excavated in Egypt was found to contain two pipes, and in addition five pieces of reed without bore or holes, and three pieces of straw suitable for making double-reed mouthpieces. See Victor Loret, “Les Flûtes égyptiennes antiques,” Journal asiatique (Paris, 1889), [8], xiv. pp. 119, 200, 201 (note), 207, 211 and 217.